Dugout

Felled by a stone axe, and burned hollow,

a ninety-foot pine rides the water reincarnated

as a dugout vaguely redolent of its fiery formation.

Three thousand years since Bronze Age Britons

sat athwart—poled through swamps, rowed lakes.

Registered signs: bird trill, antler, planet, moon,

clouds singed by the sun. They fished the depths, cooked

on deck the thrashing silvers.

From the roots of sound and trunks of words, language

feeds images that buoy our dreams. Awakened we craft

metaphors, from the Greek metaphorá, “transfer, or carry.”

Transoms, lifted from sterns, allow vessels to be sunk

for the winter in a bog as nourishing as poetry. Hidden,

then dug out, similes and metaphors also float, fresh

or fossilized—tongue of flame, or eye of a needle compass-

bound—so similar, the insensible ear does not tell them apart.

At Florida’s Pithlachocco Lake, Seminole for “the place

of long boats,” a folksinger and a teacher lead students

to discover canoes by the dozens. Archaeologists spoon-lift

from mud the shards carbon-dated to five thousand years.

In time, the people of six continents piloted dugout canoes

over oceans—some with outriggers, some with sails.

Like squirrels we cannot remember where the vehicles lie

though they branch and leaf and flower before our eyes.

Family Photograph

A satin patina of light hovers over the sofa leather

where they sit—the grown-up daughter and son, home,

together. He, cross-legged between his sister,

her scarf ornamented by a gold gift bow as corsage,

and Dad, who smiles in a wool shirt, Christmas red,

festooned by a tangle of green curling ribbon as necktie.

The father’s left hand lies snug in a brown leather glove.

The son’s lips close in amused concentration, as,

from one blue sleeve of a Santa Express party sweater

to Dad’s bare hand, he extends the four-fingered cardboard insert.

The easy grip and shake say humor’s an art between them.

In the photo we can’t see what’s done: a breakfast of pancakes

with berries and syrup, cups of coffee, espresso black.

Nor can we hear the daughter’s grin blossom into the next quip,

or the silver ornament from Lazarus, now Macy’s—a falling

portamento followed by the stutter-chirp of a mechanical mockingbird.

The same gurgle-spurts their parents had made with forefinger

tommy-guns blazing at Nazis from perches in neighborhood tree forts.

Behind Dad, a photograph of two girls. Sad little Pearl, grandma

of the siblings on the sofa, has cut her own bangs. Younger sister

stormy-eyed Nevada is tethered to sissie’s arm. They’re in button shoes,

twin shapeless dresses of mattress ticking. Pockets quiet their fists

where they stand on a porch in a southern Ohio flooded by rivers

of misfortune years before the Great Depression—a photo in grayscale.

Nothing much to suggest sentinel evergreens on a hillside of snow and stone

where the living stoop to lay flowers, and the grace note of light moves on.

I Believe I’m Sinking Down

from Cross Road Blues, now known as Crossroads

—Robert Johnson

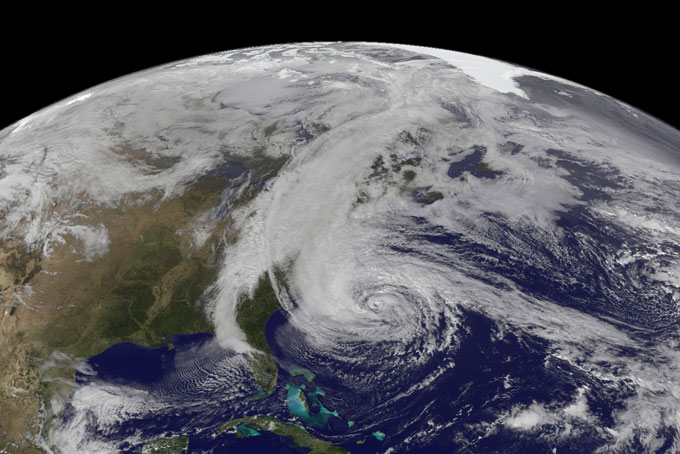

At the horizon a drowning sun,

powerless to float the graphite sea,

casts rays like grappling hooks into her chest.

Onboard, hundreds of screens flicker.

Should she watch Big Fish

or reel out her misgivings? Stage them:

wings unhinged, the fuselage and tail

thundering into an ocean too shattered to reflect?

Storms and wind shear terrify,

but she doesn’t pray the airbus through

a sky star-stung, scythe-hung. Clapton

shreds the blues of Robert Johnson, an afterworld

of resurrections in a set of loaner earphones.

By its wingless tongue, her pencil articulates

the frictions as she belies a lack of faith in last acts.