Like most of the middle age-plus pupils in the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute classes I teach at the University of Richmond, I first read John Steinbeck’s fiction as a young adult. But I chose a work of nonfiction written by Steinbeck in middle age—Travels with Charley In Search of America—to open the course I teach in American literary classics. Before we begin, I advise those who read Travels with Charley when they were young, as I did, to disregard first impressions and read it again with fresh eyes. As Steinbeck observes at the outset of the journey, what we see is determined by how we view: So much there is to see, but our morning eyes describe a different world than do our afternoon eyes, and surely our wearied evening eyes can report only a weary evening world. You don’t even know where I’m going. I don’t care. I’d like to go anywhere. I set this matter down not to instruct others but to inform myself.

As Steinbeck observes at the outset of the journey, what we see is determined by how we view.

Later, discussing the book’s significance in middle age, we recall how we explored Steinbeck’s America in our teens and twenties—driving, and riding trains, buses, and planes; experimenting with ideas; testing the patience of people who were our parents’ and Steinbeck’s age during the turbulent decade of the sixties. For many of us, the need to experience our parents’ world through the “morning eyes of youth” was the reason we read Travels with Charley the first time around. Even in middle age, Steinbeck understood the impulse to escape: When I was very young, and the urge to be someplace else was on me, I was assured by mature people that maturity would cure this itch. When years described me as mature, the remedy prescribed was middle age. In middle age, I was assured greater age would calm my fever and now that I am fifty-eight perhaps senility will do the job . . . I fear this disease incurable.

Even in middle age, Steinbeck understood the impulse to escape.

Reading Travels with Charley in maturity gives my students renewed respect for Steinbeck’s courage in answering the call of the road by driving a fitted-up camper solo from one coast to the other, with his wife’s poodle as companion and a deep understanding that “after years of struggle that we do not take a trip; a trip takes us.” Steinbeck’s itinerary in 1960 included destinations he visited on book tours years before—places he visited without fully experiencing them—and avoided high-speed super-highways, which were spreading like cancer across the map of post-war America. Steinbeck’s recognition that “When we get these thruways across the whole country . . . it will be possible to drive from New York to California without seeing a single thing” resonates with us as we recall the places we passed through along the way and reflect on the influence Travels with Charley continues to exert on how Americans think America is or was or ought to be.

We reflect on the influence Steinbeck continues to exert on how Americans think America is or was or ought to be.

All of us are amazed that Steinbeck could travel cross-country incognito until he came to Salinas, the home town he abandoned in 1925, and some identify with the sense of rejection he felt from family members and friends who failed to understand the values and ideas he expressed in the books he wrote in the 1930s. Like Thomas Wolfe, he became a stranger among his own people, though he knew better than to blame them. “Through my own efforts,” he notes, “I am lost most of the time without any help from anyone,” and he recognizes lost-ness in the people and places he encounters in Travels with Charley. A waitress has “vacant eyes” which could “drain the energy and excitement” from a room. “Some American cities are like badger holes, ringed with trash . . . surrounded by piles of wrecked and rusting automobiles [and] smothered in rubbish.” Observed firsthand, the anger of housewives protesting school desegregation in New Orleans seems inhuman and insane. “I’ve seen a look in dogs’ eyes,” he concludes, “a quick and vanishing look of amazed contempt, and I am convinced that basically, dogs think humans are nuts.”

Like Thomas Wolfe, he became a stranger among his own people, though he knew better than to blame them.

We try to avoid issues of race in class (though everyone recognizes that they still exist). As Steinbeck notes, “A dog is a bond between strangers,” and because many of us are empty-nesters, we focus instead on Steinbeck’s feelings for his dog Charley, who “loved deeply and tried dogfully,” and on the improved status of pets in his writing after Of Mice and Men. Reading or rereading Travels with Charley opens middle-aged eyes to the need for connection and companionship Steinbeck felt at a time of life when sudden loss or change—in a family or a country or a culture—can lead to alienation, loneliness, and depression. Those who think and feel after 50 will recognize the danger of despair. John Steinbeck, who made lifelong learning a creative enterprise, responded by creating an adventure for himself and us that makes Travels with Charley rewarding reading at any age.

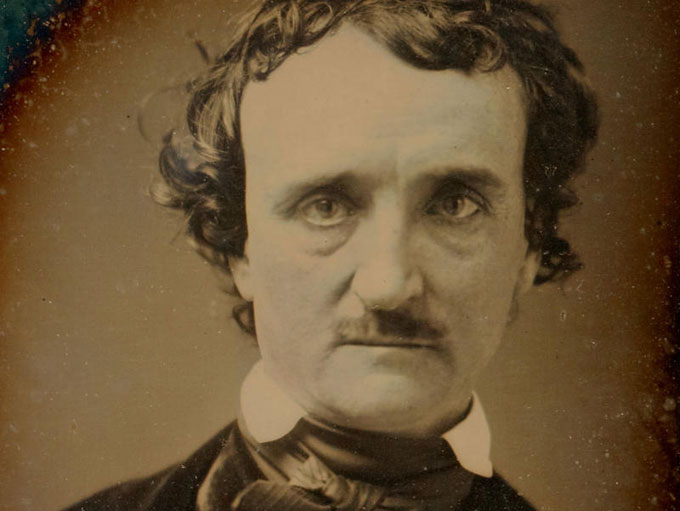

Photo of Osher Institute for Lifelong Learning class courtesy University of Richmond.