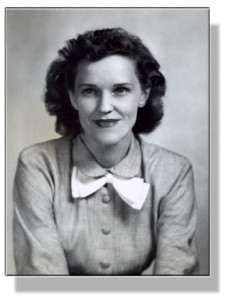

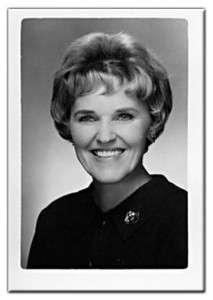

Martha Heasley Cox died in San Francisco, age 96, on September 5, 2015. Her colleague Paul Douglass celebrates her contribution to John Steinbeck studies, San Jose State University, San Francisco culture, and American literature in a heartfelt tribute to the remarkable Bay Area woman, born in Arkansas, who broke glass ceilings and gave Steinbeck studies an international home.–Ed.

I met Martha Cox in 1991, shortly after I arrived at San Jose State University from Atlanta, where the college for which I taught English and American literature had closed. As a California native, I felt lucky to have landed a faculty position in the San Francisco Bay Area, John Steinbeck territory and the source and inspiration for much American literature, from Mark Twain to the present. During my first year on the job, I attended a reading by Maxine Hong Kingston, the award-winning Bay Area novelist known for her contribution to Chinese-American literature. John Steinbeck’s dog ate one of his manuscripts, but Kingston had recently experienced a worse loss than that. She taught at Berkeley, and the 1991 firestorm that devastated nearby Oakland consumed her house, her belongings, and the manuscript of the novel she was writing at the time. Her description of pedaling her bike down the Oakland hills to escape the fast-moving blaze, a catastrophe that left permanent scars on the Bay Area psyche, riveted her audience. An American literature professor who had retired from San Jose State University and moved to San Francisco was funding the lecture series that brought Kingston, as well as American literature legends like Norman Mailer, Wallace Stegner, and Toni Morrison, to campus.

Devoted to San Jose State University and a Dream

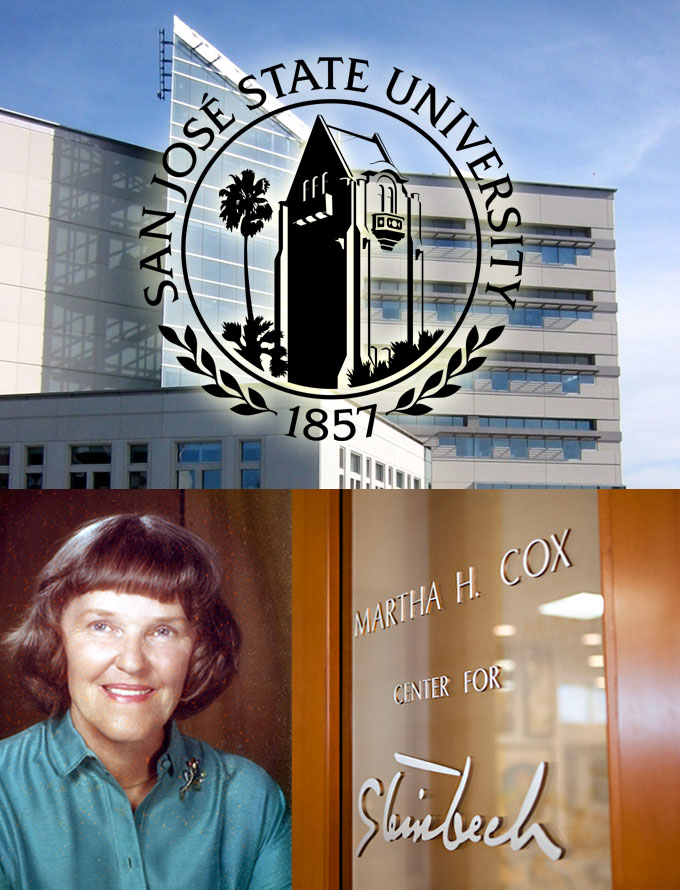

Martha Cox was a legend in her own way, and she would have tried hard to persuade John Steinbeck to lecture at San Jose State University if he were still alive. She taught in the Department of English for 34 years, endowed the lectureship that presented Kingston, and founded the San Jose State University research center devoted to John Steinbeck studies that bears her name today. In the classroom, she focused with memorable energy on the books and authors she loved most, a list that started with Steinbeck and never really ended. Greta Manville, her student, experienced Martha’s passion for John Steinbeck and American literature.

Martha Cox was a legend in her own way, and she would have tried hard to persuade John Steinbeck to lecture at San Jose State University if he were still alive. She taught in the Department of English for 34 years, endowed the lectureship that presented Kingston, and founded the San Jose State University research center devoted to John Steinbeck studies that bears her name today. In the classroom, she focused with memorable energy on the books and authors she loved most, a list that started with Steinbeck and never really ended. Greta Manville, her student, experienced Martha’s passion for John Steinbeck and American literature.

“She expected interest and enthusiasm from her students,” Greta recalls. “But Martha was no more demanding of them than she was of herself. No matter how many times she taught a novel, she reread the book before the class discussion.” Martha, who liked to get out of the classroom, took her students on day trips to Fremont Peak, Salinas, Monterey, and Cannery Row to see the places made famous in Steinbeck’s writing about California. She loved the land and the people, and creating a center for Steinbeck studies at San Jose State University became a mission.

Although their birthdays were only one day (and 17 years) apart, Martha’s background was different from Steinbeck’s. Born on February 26, 1919 in Calico Rock, Arkansas, she majored in English at Lyon College, a small school in Batesville that she loved and later honored with gifts. After graduation she enrolled at the University of Wisconsin, returning to her home state to complete her master’s degree at the University of Arkansas in 1943. Following World War II, she continued graduate study at the University of Texas, but, like John Steinbeck, couldn’t get home out of her bones and returned to the University of Arkansas, where she received her Ph.D. in 1955.

Although their birthdays were only one day (and 17 years) apart, Martha’s background was different from Steinbeck’s. Born on February 26, 1919 in Calico Rock, Arkansas, she majored in English at Lyon College, a small school in Batesville that she loved and later honored with gifts. After graduation she enrolled at the University of Wisconsin, returning to her home state to complete her master’s degree at the University of Arkansas in 1943. Following World War II, she continued graduate study at the University of Texas, but, like John Steinbeck, couldn’t get home out of her bones and returned to the University of Arkansas, where she received her Ph.D. in 1955.

Then, much like Steinbeck during the same period, she pulled up stakes and left her people’s country for good, moving to the San Francisco Bay Area to teach English composition and American literature at San Jose State University. She and her husband Cecil Cox eventually divorced, but remained friends: Cecil drove Martha back to Arkansas when Lyon College recognized her for endowing the professorship in American literature named in her honor, and the Leila Lenore Heasley Prize for distinguished writers, named in honor of her sister. Terrell Tebbetts, the first Lyon College professor to hold the Cox Chair in American Literature, says that “her gifts have helped to keep her alma mater well-connected to both the literary and the scholarly worlds.” From 1955 until her death two weeks ago, she performed the same service for San Jose State University, extending the school’s reach and impact in the role of scholar-philanthropist.

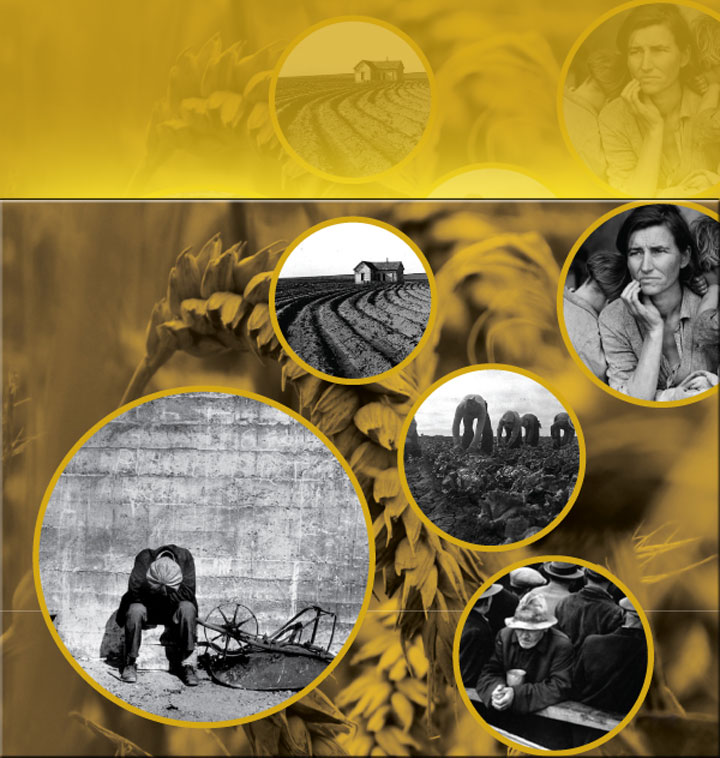

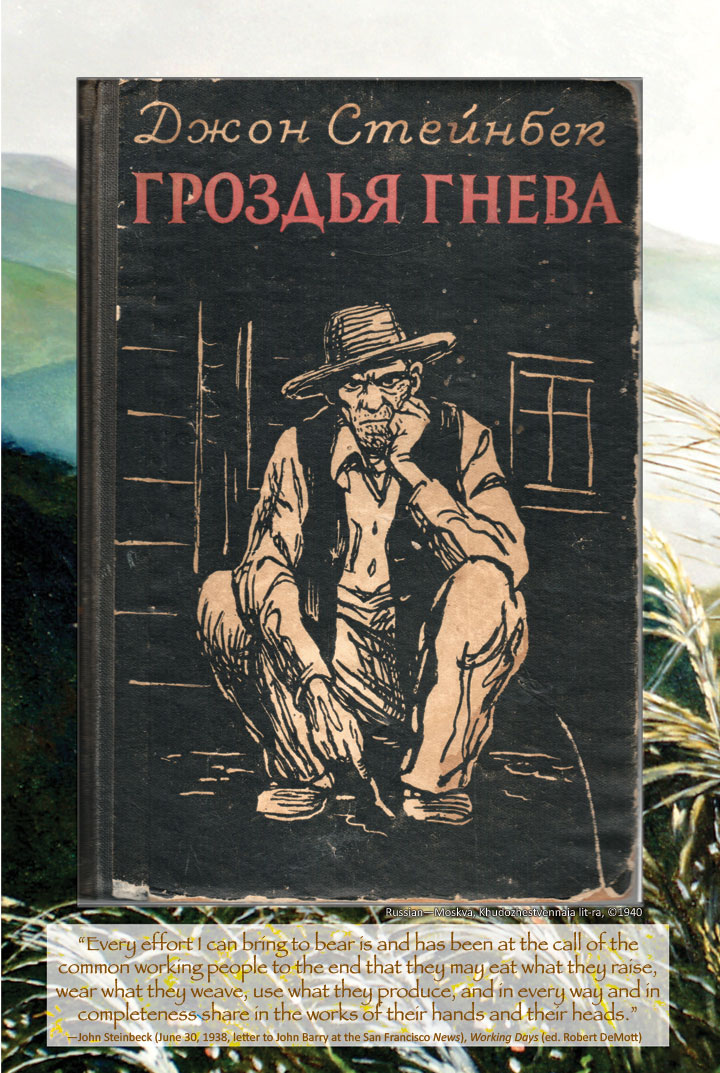

Martha made her fortune the old-fashioned way, through hard work as an ambitious academic author and careful investment in stocks and real estate. A child of the Great Depression, she wanted every dollar, like every moment in life, to count. She was a practical woman who wrote practical books: texts on writing, critical studies and guides for readers, and bibliographies useful to scholars of American literature. She collected books the way Steinbeck did: for reading, not for show. Recently, I packed up her personal library in San Francisco to bring her books to San Jose State University. Even her autographed first-editions are thoroughly thumbed. She was a friend and bibliographer of the author Nelson Algren, a major figure in mid-20th century American literature, and he sent her signed copies of his novels with personal notes. These rare books were worn with hard use. Most of the works by John Steinbeck she owned are heavily-annotated paperback editions with yellowing pages that fall out when disturbed. Martha was a Southerner, and William Faulkner was well represented on the shelves of her San Francisco apartment. But John Steinbeck became her chief scholarly pursuit after 1968, the year Steinbeck died and her dream for a Steinbeck center at San Jose State University began.

Martha made her fortune the old-fashioned way, through hard work as an ambitious academic author and careful investment in stocks and real estate. A child of the Great Depression, she wanted every dollar, like every moment in life, to count. She was a practical woman who wrote practical books: texts on writing, critical studies and guides for readers, and bibliographies useful to scholars of American literature. She collected books the way Steinbeck did: for reading, not for show. Recently, I packed up her personal library in San Francisco to bring her books to San Jose State University. Even her autographed first-editions are thoroughly thumbed. She was a friend and bibliographer of the author Nelson Algren, a major figure in mid-20th century American literature, and he sent her signed copies of his novels with personal notes. These rare books were worn with hard use. Most of the works by John Steinbeck she owned are heavily-annotated paperback editions with yellowing pages that fall out when disturbed. Martha was a Southerner, and William Faulkner was well represented on the shelves of her San Francisco apartment. But John Steinbeck became her chief scholarly pursuit after 1968, the year Steinbeck died and her dream for a Steinbeck center at San Jose State University began.

Martha made her fortune the old-fashioned way, through hard work as an ambitious academic author and careful investment in stocks and real estate.

I don’t know how much she knew about Steinbeck’s life before she moved to California, but Greta Manville observed that Martha “lived and taught near ‘Steinbeck Country,’ and believed it only fair that the Nobel laureate be recognized in his own territory.” Within three years of Steinbeck’s death (he is buried in Salinas), Martha managed to drum up support for her vision of a Steinbeck center from everyone who would listen, including major Steinbeck scholars such as Warren French, Peter Lisca, Robert DeMott, Jackson Benson, and the members of the John Steinbeck Society founded by Tetsumaro Hayashi. She became friends with Elaine Steinbeck, John’s widow, and Thomas Steinbeck, his son. She was passionate and she was persuasive.

Within three years of Steinbeck’s death, Martha managed to drum up support for her vision of a Steinbeck center from everyone who would listen.

Martha enlisted San Jose State University students like Ray Morrison in fundraising, and she traveled whenever and wherever necessary to acquire copies of book reviews, academic papers, and feature articles for the Steinbeck center she founded on campus in 1971. Greta Manville, a former Steinbeck Fellow, recalls frequent trips to Stanford, Berkeley, Austin, and New York, where Martha searched the New York Public Library, the Lincoln Center Library, and the archives of Viking Press, Steinbeck’s publisher. Manville, who created the Steinbeck center’s online bibliography, accompanied Martha on her search-and-find mission to New York in 1977: “We worked very hard all day long for a week—and went to the theater each night. Our somewhat fleabag hotel was right in the heart of the theater district. Martha was a walker. . . so we walked everywhere, even from Lincoln Center on 62nd Street through Central Park to a restaurant near the hotel—in time for the evening performances around 42nd Street.”

Martha enlisted San Jose State University students in fundraising and traveled whenever and wherever necessary to acquire copies of book reviews, academic papers, and feature articles for the Steinbeck center she founded on campus in 1971.

Martha’s case for John Steinbeck was difficult to resist. Her colleagues in the Department of English weren’t exempt from service to the cause. Arlene Okerlund, later San Jose State University’s dean and academic vice president, was a young visiting professor when Martha’s quest began and quickly enlisted. “I met Martha Cox in 1969, when the chair of the English department assigned me to share an office with her,” she recalls. “I was a temporary lecturer (not tenure track) and quite intimidated by one of the more awesome senior full professors in the department.” Martha had a reputation, and resisters, at San Jose State University. Arlene was not among them.

Martha’s case for John Steinbeck was difficult to resist. Her colleagues in the Department of English weren’t exempt from service to the cause.

The two grew close, working together on the pioneering Steinbeck conferences Martha organized at San Jose State University in 1971 and 1973 and remaining warm friends in retirement. As her health declined in recent years, Martha depended on the help and counsel of her younger colleague from those early days. Now a resident of Los Gatos, the town where Steinbeck completed Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath, Arlene continues to write books and articles about Renaissance literature, her specialty, and serves as the executor of Martha’s estate.

As her health declined in recent years, Martha depended on the help and counsel of Arlene Okerlund, her younger colleague from those early days.

I live even farther from San Francisco than Arlene does, but I also became Martha’s friend. In later years, I would make my way to San Francisco to pick up Martha for events at San Jose State University, such as readings by authors like Joyce Carol Oates. During the drive Martha talked my ears off. She had plans for Steinbeck events; she asked how her endowment funds were being spent; she fretted that some real estate she had given San Jose State University was sitting on the market too long; she was curious about who was being considered as the next Cox Lecturer on campus; she praised the way Lyon College treated donors and suggested that improvements could be made in fundraising at San Jose State University; she hoped that, someday soon, a Steinbeck Fellow would win the California Book Award for fiction.

From San Jose State University to San Francisco City Hall

When she retired from San Jose State University in 1989, Martha moved to a Van Ness Avenue apartment with a dramatic view of San Francisco City Hall. Unfit for idleness, she joined the Commonwealth Club, an energetic engine of Bay Area culture with moving parts, literary and political and artistic, that appealed to Martha’s eclecticism. Jim Coplan, a staff member, became Martha’s friend and confidante, and the California Book Awards given annually by the organization occupied her attention, another cause in the service of American literature.

The California Book Awards given annually by the Commonwealth Club occupied her attention, another cause in the service of American literature.

Created to counter East Coast neglect of Western writers, a bias in American literature lamented by John Steinbeck, the California Book Award for fiction went to Steinbeck three times: for Tortilla Flat (1935), In Dubious Battle (1936), and The Grapes of Wrath (1939). Jim Coplan says that Steinbeck’s triple run “led to the establishment of the Steinbeck Rule for the awards, which limited a single author to three Gold Medals.” Until Martha asked Jim how she could help improve the program, authors selected for awards received medals, but no money. According to Jim, Martha’s gift of $50,000 was matched by Bill Lane, the publisher of Sunset Magazine, adding a touch of green to the Commonwealth Club’s coveted Gold and Silver Awards.

Martha’s gift of $50,000 was matched by Bill Lane, the publisher of Sunset Magazine, adding a touch of green to the coveted Gold and Silver Awards.

“Martha put her resources to work where her heart lay,” observes Jim, and her time and mind came with her money. She served on the California Book Awards jury until she was 92, reading 100-200 books submitted every year. San Francisco is a walking town, and Martha would catch the bus to Commonwealth Club’s offices, pick up a bag of books, lug them home and churn through them all, then repeat the process the next week. She expressed her horror that anyone would consider skimming through the entries, despite their number. For her, each author deserved equal attention, each book cover-to-cover assessment. At the 2013 California Book Award ceremony, she received her own Gold Medal, given in recognition of her remarkable performance. Similar celebrations honored her achievements at San Jose State University.

Martha’s Springsteen Moment on Behalf of Steinbeck

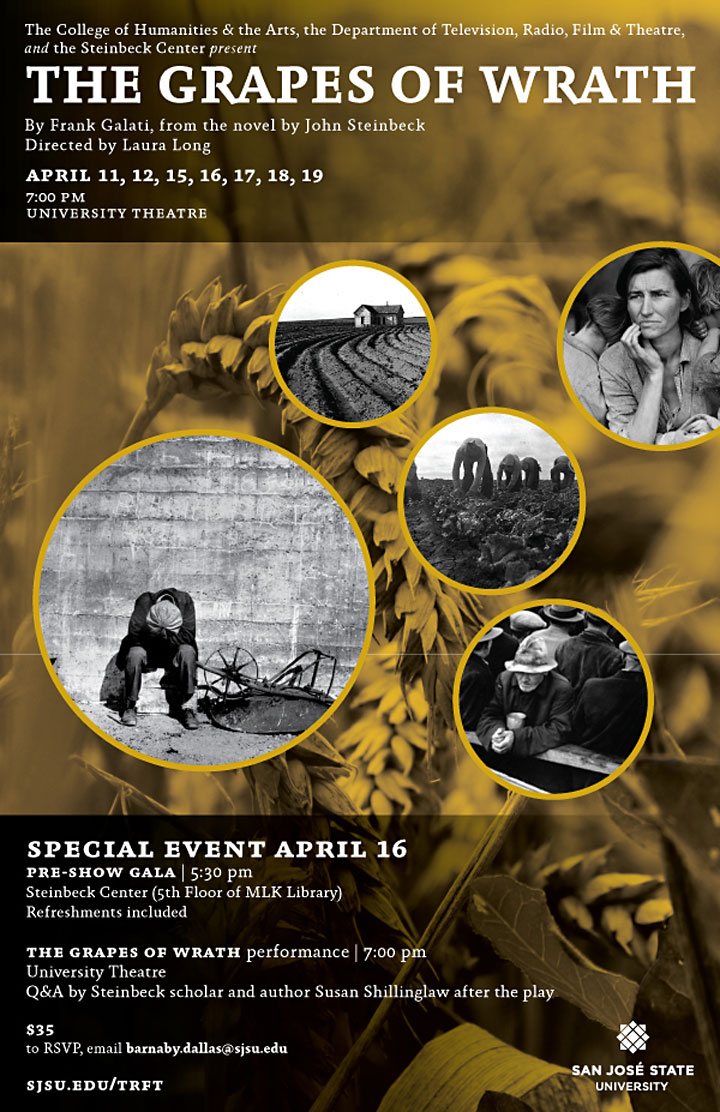

My regular contact with Martha began in 1993-94, when I filled in as interim director of the Steinbeck research center while Susan Shillinglaw, the longest-serving director in its history, was on leave. Now located on the fifth floor of the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library, a joint venture of San Jose State University and the City of San Jose, the center was housed at the time in the Wahlquist Library, the San Jose State University building the new library replaced.

My regular contact with Martha began in 1993-94, when I filled in as interim director of the Steinbeck research center while Susan Shillinglaw was on leave.

During my year as interim director, Steinbeck studies moved to larger quarters in the old library building, space that needed shelves and furnishing and, thus, funding. Martha was in San Francisco, but her entrepreneurial example endured at San Jose State University. When Bruce Springsteen wanted to tie the release of his 1996 Ghost of Tom Joad album to John Steinbeck, Susan’s warm relations with Steinbeck’s widow and literary agency led to an inspired idea. Springsteen accepted the Steinbeck “in the souls of the people” Award, now a regular fundraising activity of the Steinbeck Studies Center, at a sold-out benefit performance attended by Martha, who was thrilled: “When she met Bruce Springsteen,” Susan recalls, “she stood next to Elaine Steinbeck, happily bookended by two people who shared her passion for Steinbeck.”

When Bruce Springsteen wanted to tie the release of his 1996 Ghost of Tom Joad album to John Steinbeck, Susan’s warm relations with Steinbeck’s widow and literary agency led to an inspired idea.

In 1997, Susan organized a dedication ceremony for the refurbished Wahlquist Library space at which the center was named the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies. “I think she was happy,” says Susan. “I know she left an indelible imprint on San Jose State University, on all who knew her, certainly on me.” Later, I sat down with Martha and Jack Crane, dean of the College of Humanities and the Arts, to discuss Martha’s new dream: a fellowship program to bring scholars and creative writers together to collaborate in Steinbeck’s name. Steinbeck’s interests were diverse, so the idea made sense to Martha, if not to skeptics. How could a public institution like San Jose State University afford it, critics asked? Doubters failed to deter Martha when she started the campus center for Steinbeck studies in 1971, and the years failed to dim her determination. I volunteered to administer the program on top of my teaching load if funds could be found. Martha agreed to create an endowment to pay for Fellows’ stipends, and promised to do more in her estate planning.

Martha’s new dream: a fellowship program to bring scholars and creative writers together to collaborate in Steinbeck’s name. Steinbeck’s interests were diverse, so the idea made sense to Martha, if not to skeptics. How could San Jose State University afford it, they asked?

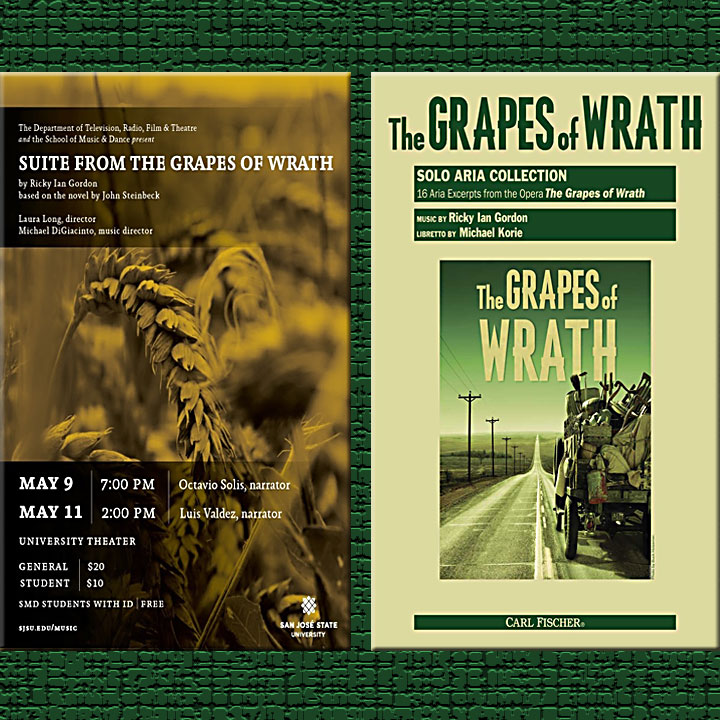

Today the Steinbeck Fellows program, like the Steinbeck award, is one of the most public and successful activities of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies. I administered the program for 12 years; when I succeeded Susan as director in 2005, I had gotten to know Martha’s interests and inclinations pretty well. Unsurprisingly for a person who was passionate about John Steinbeck, Martha’s interests also included theater, a colorful part of San Francisco’s cultural fabric. She contributed generously to Eureka Theatre, the plucky group that commissioned Tony Kushner’s Angels in America. She was a loyal patron of the Magic Theatre in Fort Mason, where Sam Shepard had been writer in residence. She gave money for free public readings of new plays at the Magic, the Exploratorium, the Palace of Fine Arts, and the Commonwealth Club. My wife Charlene and I enjoyed accompanying her to the performances she funded. Like John Steinbeck, Martha was in her element in San Francisco.

An Inspirational Founder for an International Resource

But Martha’s heart stayed with John Steinbeck and, through thick and thin, with San Jose State University. She hosted gatherings of the Steinbeck Fellows at her apartment, and the center named for her continued to benefit from her support. Significantly, each of the directors who succeeded her reflected her entrepreneurial spirit, devotion to diversity, and global perspective. The Martha Heasley Cox Center has become an international resource, an outcome John Steinbeck would approve.

The Martha Heasley Cox Center has become an international resource, an outcome John Steinbeck would approve.

Robert DeMott, Edwin and Ruth Kennedy Distinguished Professor at Ohio University, took leaves of absence from Ohio in the mid-1980s to serve as interim director and teach San Jose State University classes in the subjects that Martha taught: American literature, John Steinbeck, and creative writing. A poet as well as an internationally recognized Steinbeck scholar, Bob said this: “Martha Cox had vision and gumption and foresight where John Steinbeck was concerned. Establishing the Steinbeck Research Center (as it was then called) was an act of bravado, endurance, and love. All of us—scholars, students, enthusiasts, and even casual readers of Steinbeck’s work and his legacy–will always be in her debt.”

‘All of us—scholars, students, enthusiasts, and even casual readers of Steinbeck’s work and his legacy—will always be in her debt.’—Robert DeMott

Susan Shillinglaw, one the most respected Steinbeck scholars in the world, was director for 17 years and continues to teach San Jose State University’s course on John Steinbeck while serving as interim director of the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas. She summed up Martha’s influence on others: “Her love of books, theater, writers, San Jose State University, and Lyon College was palpable—and unforgettable.”

‘Her love of books, theater, writers, San Jose State University, and Lyon College was palpable—and unforgettable.’—Susan Shillinglaw

Nick Taylor, my successor as director, is a young novelist who, like Martha and me, left the South to take a teaching job at San Jose State University. He spoke for the future of Steinbeck studies: “Martha Heasley Cox was the perfect English professor for Silicon Valley, an impatient entrepreneur who took the future into her own hands, founding a major research center and a fellowship program out in her intellectual garage. The more I learn about her career, the more impressed I am. She lived a 20th century life, but she was a model for 21st century academics like me.”

‘Martha Heasley Cox was the perfect English professor for Silicon Valley, an impatient entrepreneur who took the future into her own hands.’—Nick Taylor

San Jose State University gave Martha Heasley Cox its prestigious Tower Award in 2000. The woman who gave Steinbeck studies a home will be honored at a memorial event attended by friends, colleagues, and schools officials, including Lisa Vollendorf, the enterprising dean of the College of Humanities and the Arts who put Martha’s contribution in perspective for this piece: “Martha Heasley Cox’s visionary generosity helped San Jose State University secure a position on the international stage as an institution dedicated to furthering the values embraced by Steinbeck’s life and writing.” The October 6, 2015 celebration of Martha’s life will take place at 2:00 p.m. on the fifth floor of the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library, in the hospitable home for Steinbeck studies she started at San Jose State University 45 years ago. Her spirit lives on in the house.

Memorial gifts in honor of Martha Heasley Cox may be made to the Tower Foundation of San Jose State University or to Lyon College in Batesville, Arkansas.