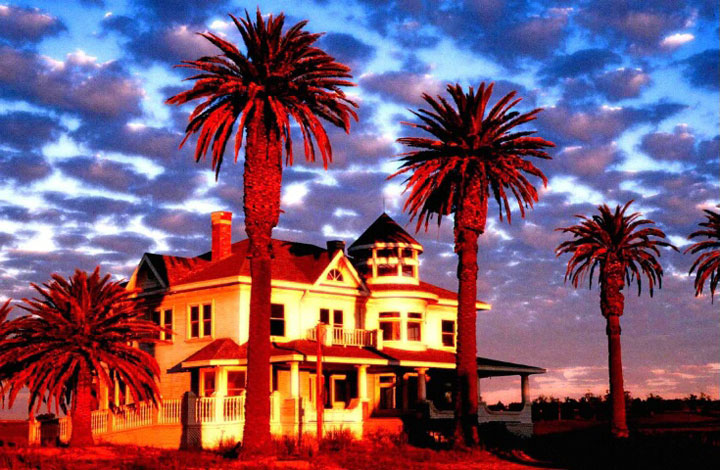

Who would believe ultra-rich Hollywood

would slander itself? This dilapidated hotel

has mirrors on the ceilings, pink champagne

effervescing 24/7 in lighted fountains—

all right, it’s California and, by extension,

the republic of sunlight and worn-out souls.

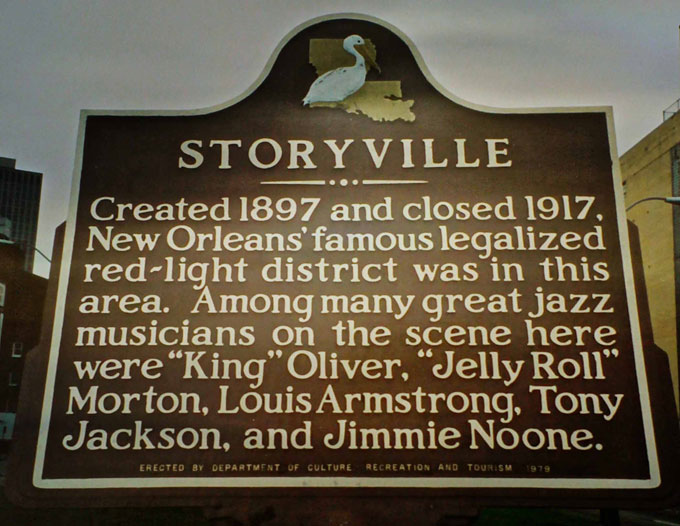

If you listen, what you hear is the vox populi

of Failure. Hear it? You could do worse

than remember the message of some music

is the truth because what it says, in any case,

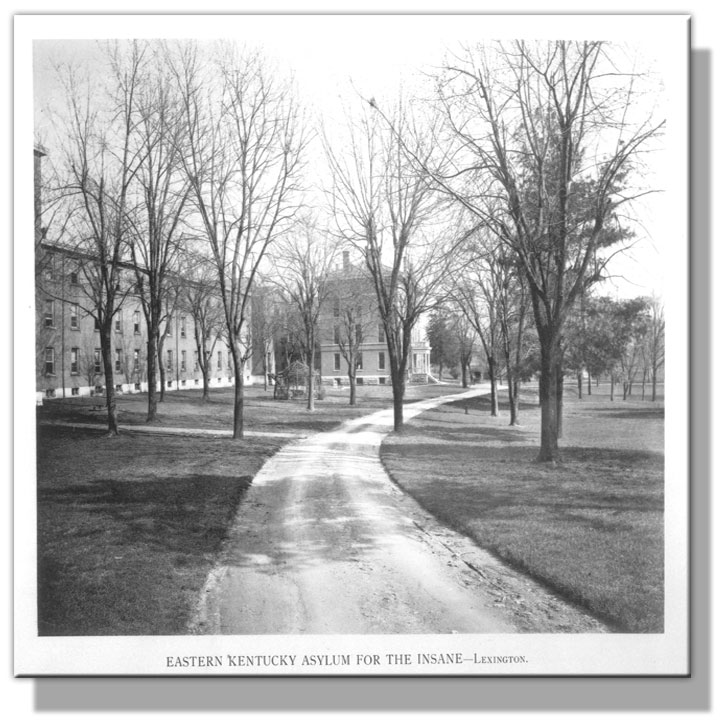

is We Have Blown It. Which is accurate and

true. And so after “you can check out anytime

you like but you can never leave” breaks off,

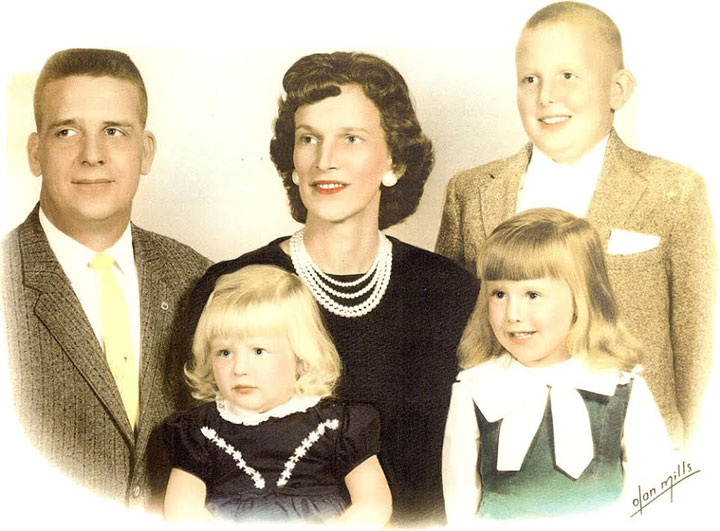

that other national anthem, beautiful light,

plays and the wrecked world assumes

an ordinary but recognizable shape.