What would John Steinbeck have to say about the COVID-19 crisis? What would he focus on? I think it would be the plight of the homeless in places like San Francisco and Los Angeles, teeming with people struggling to survive without shelter or support.

Sleepless in Los Angeles, Cold in San Francisco

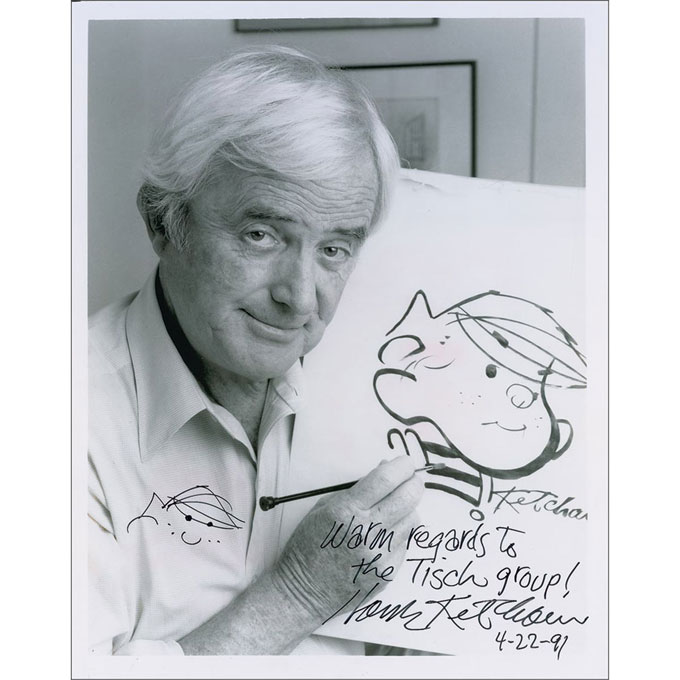

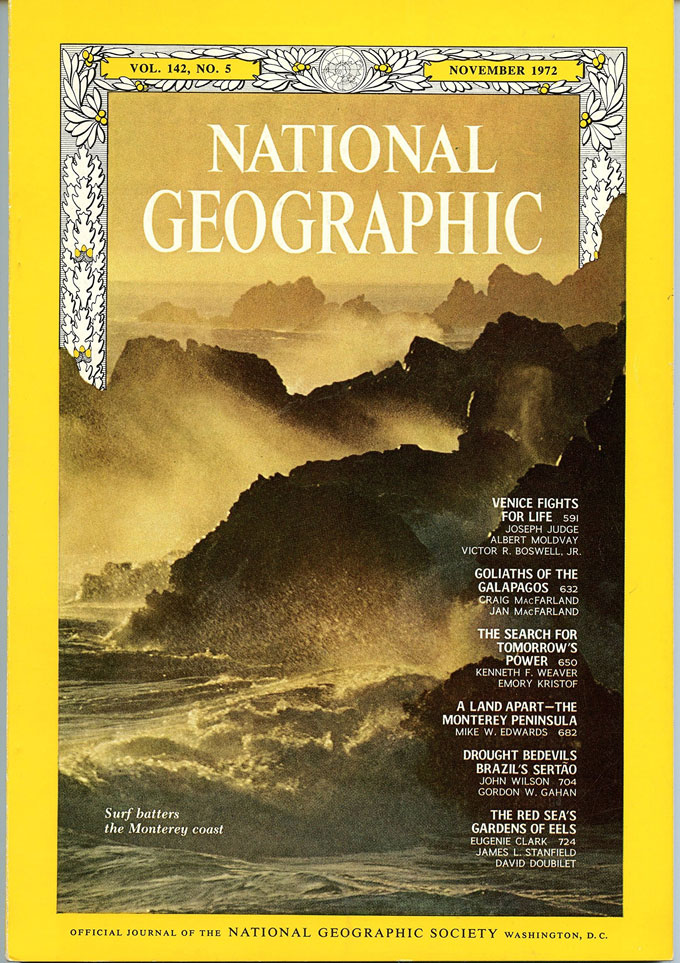

I was “homeless” several times in Los Angeles. I don’t pretend it was a big deal. I was young. I could have returned to my family in the Midwest. And there wasn’t a virus on the loose threatening death. But I had a taste of what it was like to sleep on beaches and park benches on cold nights, amidst dangers real and imagined. One night I woke to a gang fight going on nearby and decided it would be just as easy to be homeless in San Francisco as Los Angeles. Putting everything I owned in a battered leather suitcase, I hitchhiked north toward San Francisco, stopping along the way in Monterey, a town I had never seen. It would be my first real exposure to John Steinbeck, beginning with the Monterey Public Library, a display of Steinbeck’s books in the window attracting me.

I had a taste of what it was like to sleep on beaches and park benches on cold nights, amidst dangers real and imagined.

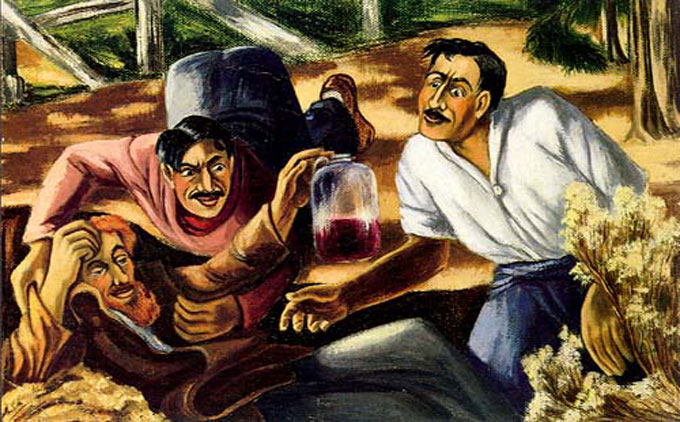

I picked a copy of Of Mice and Men off the shelves. As the homeless do to this day—or once did, since libraries are currently closed across much of the country, making a huge difference in the lives of the homeless—I could get warm while reading. George and Lennie’s story is set in South Monterey County, which I had passed through that morning. I read till the library closed, lingering over passages as I do when something moves me. George and Lennie were, after all, in a way homeless too.

I picked a copy of Of Mice and Men off the shelves. I could get warm by reading.

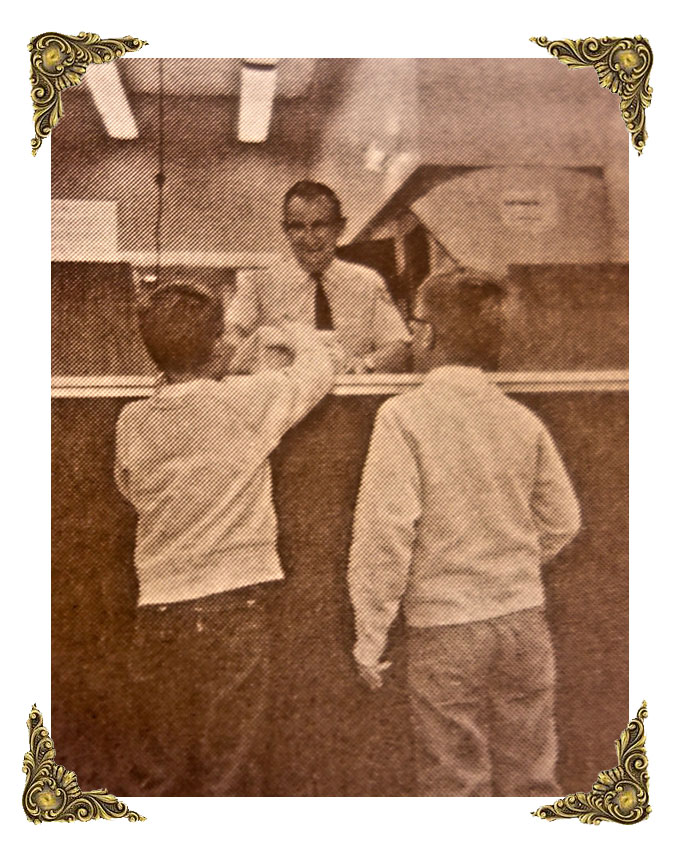

Then I walked down a street called Calle Principal, leading to an old building with a sign reading “Hotel San Carlos.” I stood out front with my leather suitcase wishing I had enough money for a room. A man came along, and after talking he went into the hotel and convinced the desk clerk I should get a good deal on a room for the night. Decades later I would write a short story about John Steinbeck and his wife Carol and that raffish old hotel. Writing from my memories of that lonely evening in Monterey, it was easy to set the scene, back in the 1930s: “They made their way clumsily down Calle Principal toward the hotel . . . which was in the Spanish style with a plaza and fountain. In the lobby a moth flit from lamp to lamp . . . .“

I stood out front with my leather suitcase wishing I had enough money for a room.

The area intrigued me. In the morning I walked along the shoreline to the town of Pacific Grove, then hitchhiked the six or so miles to the Carmel Mission. The room at the San Carlos no longer available and having money for only food and cigarettes (yes, I smoked), I hitched on to San Francisco that evening. I learned The City is a harder place to be homeless than Los Angeles because it is colder, especially when the sea wind blows in from the bay. After several days meeting “partially homeless” people like myself, I hitched my way back to Los Angeles.

The City is a harder place to be homeless than Los Angeles because it is colder.

I was going to write about other homeless experiences in Los Angeles—having my clothes locked up because I owed rent at the Mark Twain hotel, which I chose because I’m from Missouri . . . sleeping at night under a golf course tree, caddying during the days to earn money . . . having a car for a time, parking it on Santa Monica beaches and bathing in the ocean . . . on a foggy night pulling over to sleep on Mulholland Drive, discovering at sunrise that only a few feet separated the car and me from a plunge into the San Fernando Valley . . . savoring the warmth of sitting in class at Los Angeles City College after cleaning up in the school’s lavatory.

What I Learned from Being (Briefly) Homeless

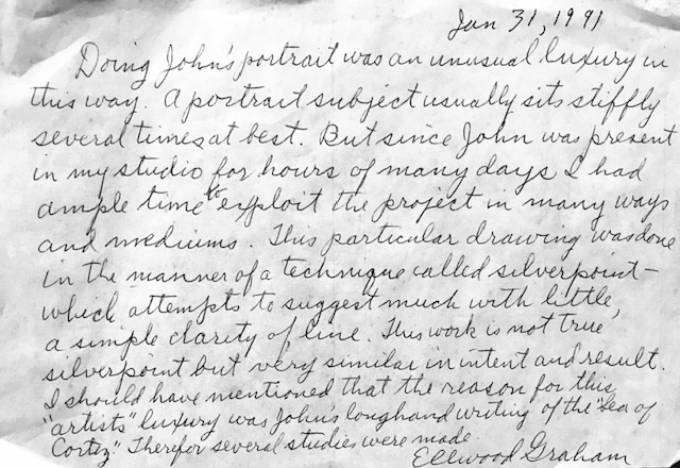

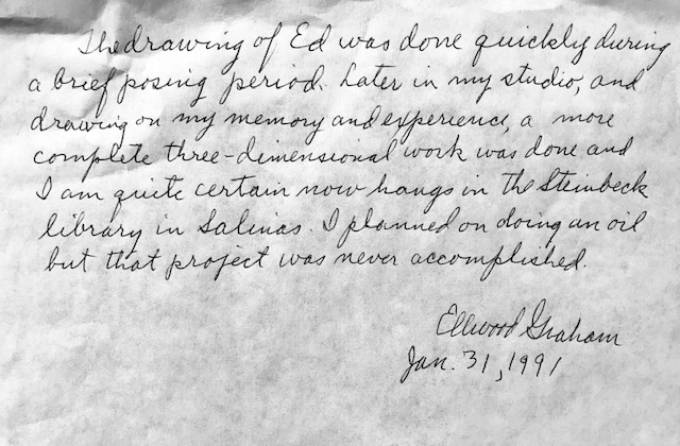

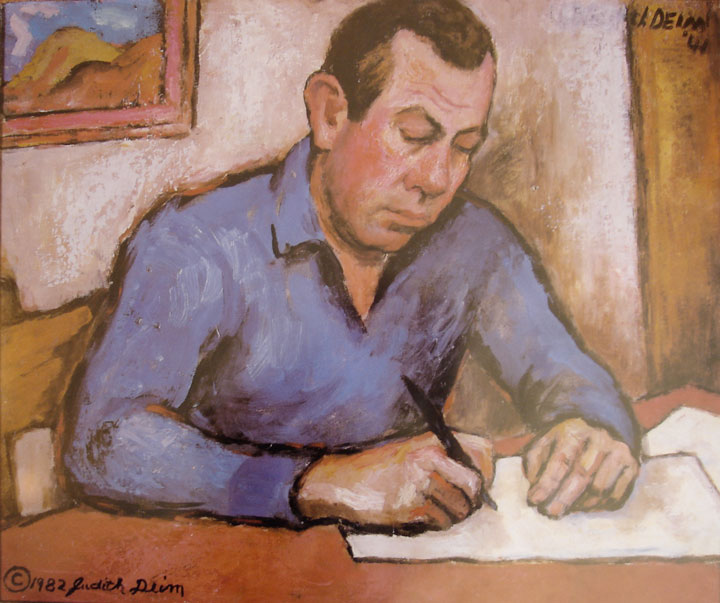

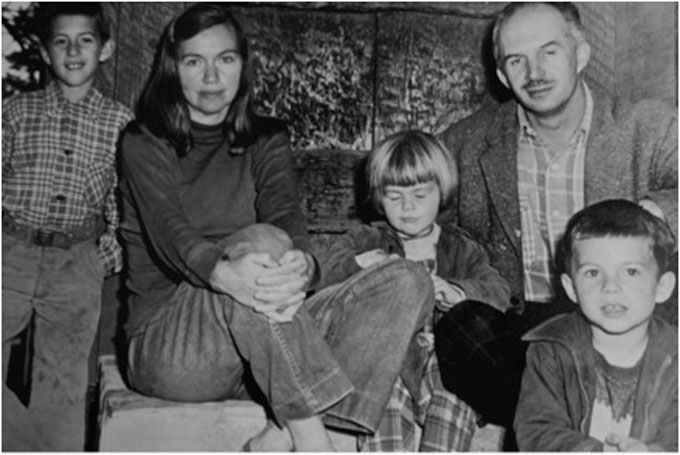

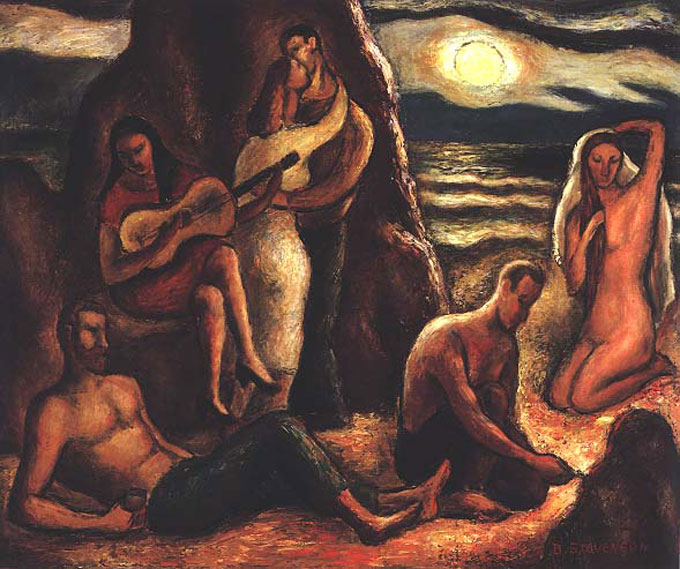

But when it comes down to it, I simply owe a lot to being briefly homeless. It introduced me to the Monterey Peninsula. John Steinbeck’s Pacific Grove eventually became my new home, the place where my wife Nancy and I raised our daughters Amy and Anne. I wrote for the Monterey Herald, learning more about Steinbeck from a soulful city editor named Jimmy Costello. Jimmy had been Steinbeck’s friend and told me of the incident at the Hotel San Carlos. He had been there. The Carmel Mission I’d hitchhiked to from Monterey became the site for the premiere of one of my plays. And I was honored to co-curate, with Patricia Leach, the inaugural art exhibition at the National Steinbeck Center in nearby Salinas. It was called This Side of Eden: Images of Steinbeck’s California, and the works on display included several depictions of homelessness, among them Maynard Dixon’s prophetically titled “No Place to Go.” Unfortunately, the subject of the painting is just as relevant today as it was in the 1930s.

I wrote for the Monterey Herald and learned more about Steinbeck from a soulful city editor named Jimmy Costello.

The greater irony for me is that the same Monterey Public Library which helped introduce me to the world of John Steinbeck recently asked if I would take part in a panel discussion on writing planned for late April. The event has been postponed, of course, because of the coronavirus. When it is rescheduled it will be a sign that that we have survived this latest test of our shared humanity—and that those living with homelessness can still count on libraries for warmth . . . as well as a good read.