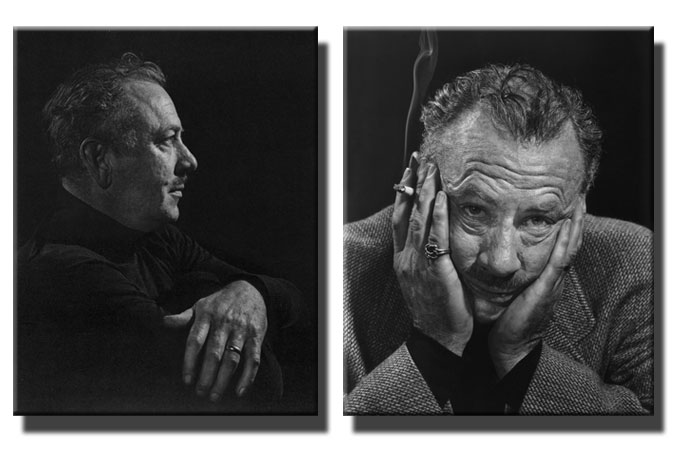

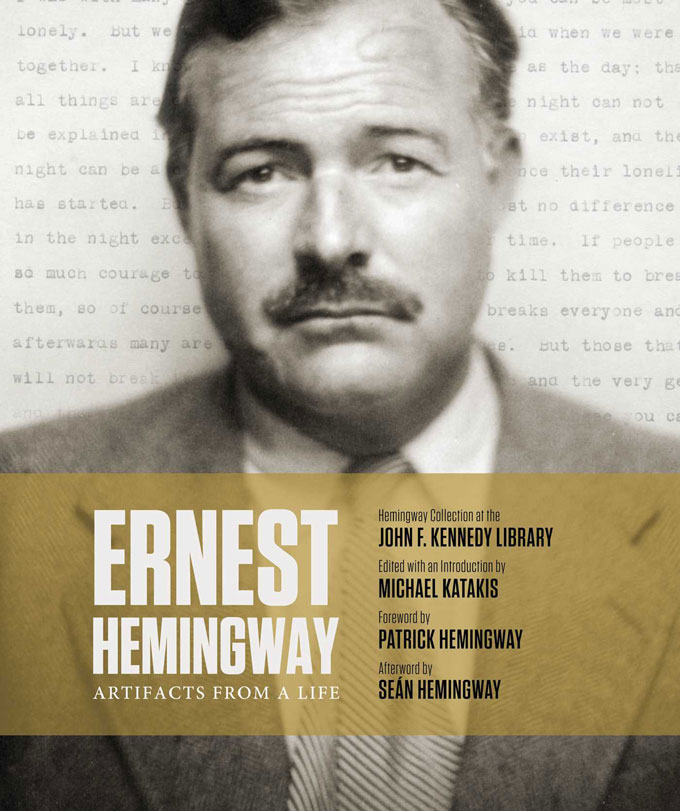

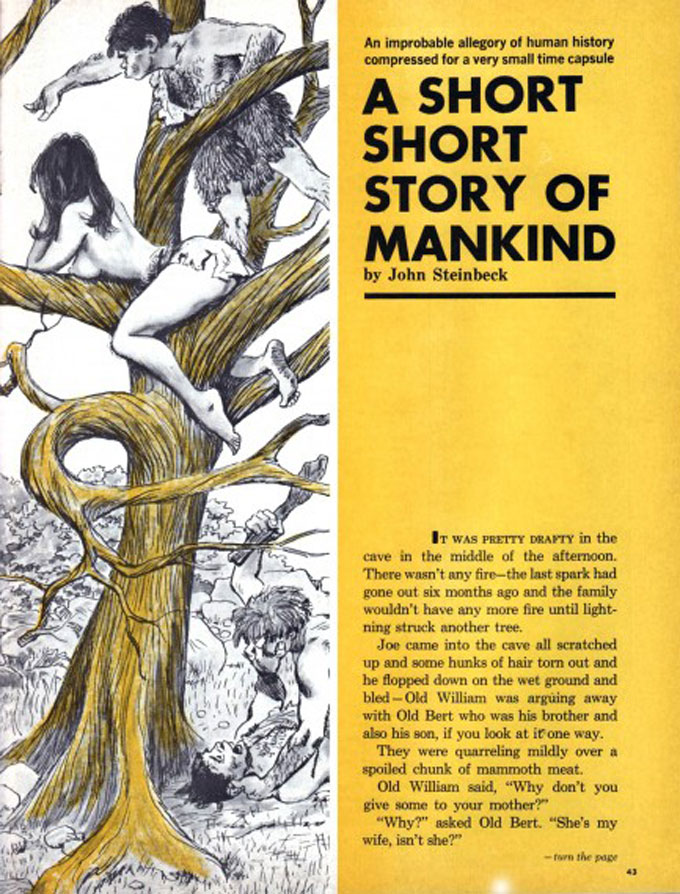

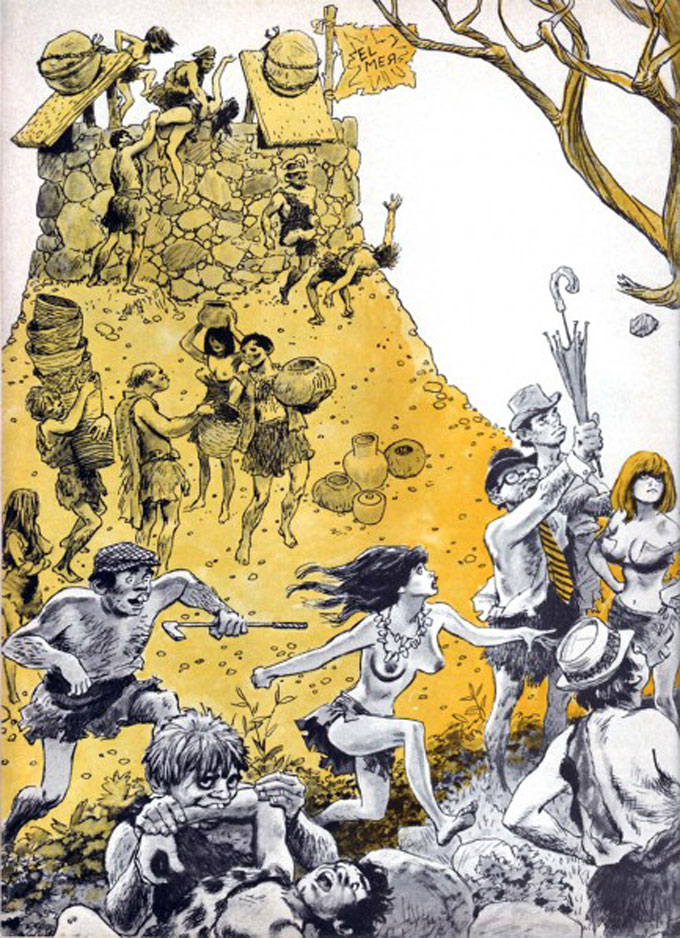

John Steinbeck said Montana was the state he’d pick to live in if he hadn’t been born in California, or become a citizen of the world who now called Manhattan home. In the early short stories of The Pastures of Heaven (1932) and The Long Valley (1938), the author of The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden showed how vast spaces, violent events, and the struggles of victims and villains conspire to make good men dangerous and dangerous men deadly, stripping the veneer off civilization to expose the coarseness, and the fineness, of the essential human grain. Like Steinbeck, the American writer Michael Katakis can claim global citizenship (Carmel, Paris, London), international connections (as a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and executor for Hemingway’s literary estate), and—as demonstrated in his latest book, Dangerous Men—an ability to transpose personal loss (the tragic death of his young wife, the anthropologist Kris L. Hardin) into a particularized locale (rural Montana) as remote from most readers’ experience as Hemingway’s Pamplona or Steinbeck’s Big Sur.

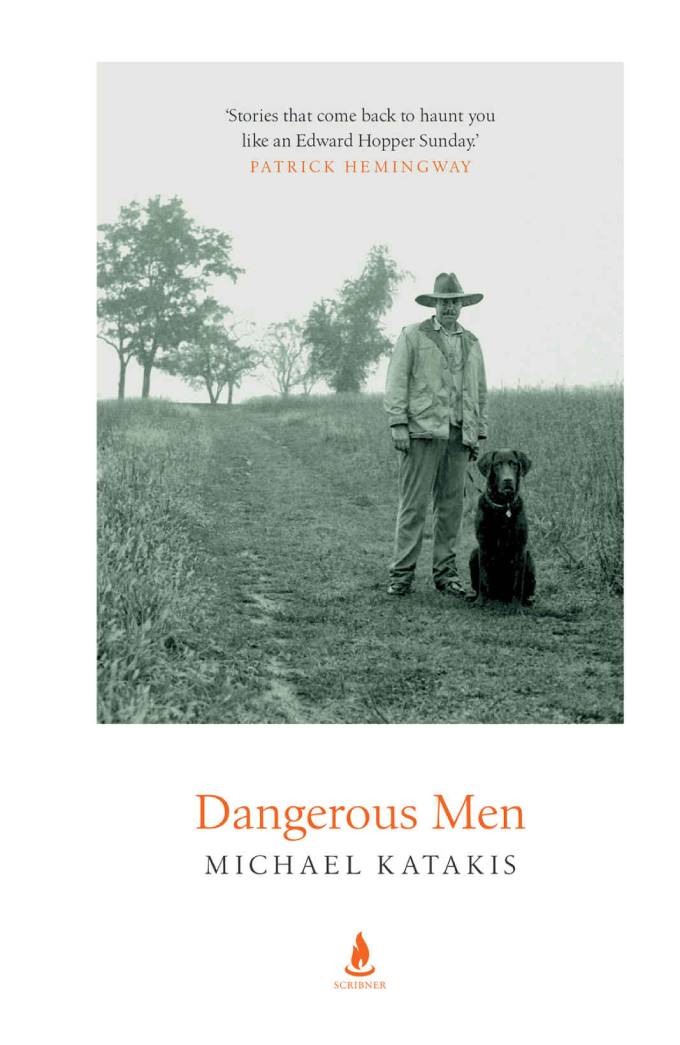

Dangerous Men is Michael’s first work of fiction, and “Hunter’s Moon”—the most nakedly autobiographical of the interconnected short stories in the collection—was written in Montana 16 years ago, long before Kris died from a brain tumor. Much of the rest of the writing was done over coffee or an appertif at a Paris-boulevard café, in a process of self-recovery that one doubts is finished, or ever will be. The result is a work whose dark tone and deadly theme are announced in the epigraph from The Pastures of Heaven that opens “The Fence,” the first story; the second, “Home for Christmas,” ends with a bitter reversal worthy of O’Henry, or the occasional Steinbeck. The remaining stories recount the revenge odyssey of a wandering hero with the wonderful name of Walter Lesser, a latter-day cowboy and Gary Cooper lookalike who ends up, like Tom Joad, as a larger-than-life legend. Raja Shehadeh, the author of Palestinian Walks: Notes on a Vanishing Landscape (2008), has described Dangerous Men as “a work of great sensitivity and lyrical beauty.” For fans of John Steinbeck, the Montana short stories of Michael Katakis are also a form of continuing communion with the spirit of The Pastures of Heaven—a place where violent events play out against vast spaces under the sign of the Hunter’s Moon. Highly recommended for Steinbeck readers and others safe-sheltering from the dangerous men in Washington, D.C.

Hunter’s Moon photograph courtesy of the Daily Express.