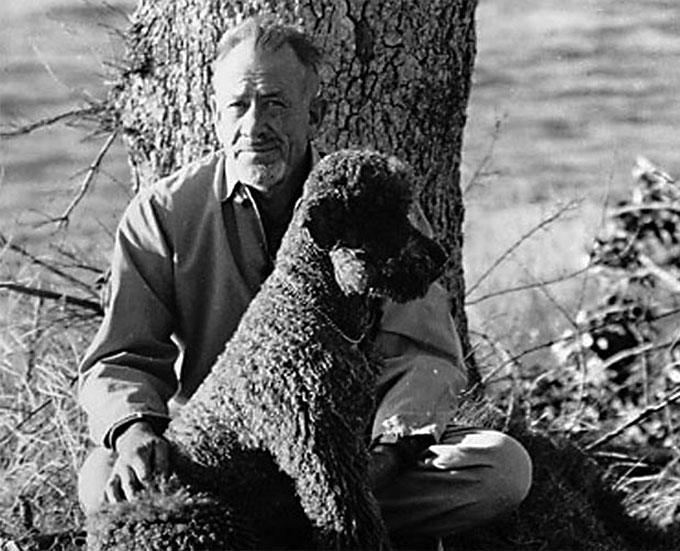

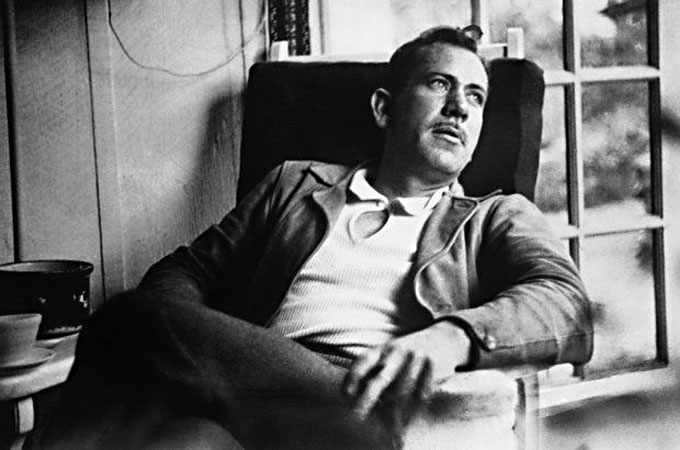

Though he occasionally misused or misspelled words, John Steinbeck wrote to be understood, often revising sentences, paragraphs, and whole chapters before publishing. Unfortunately, blog posts written about Steinbeck for online magazines, ostensibly with grammar-checking editors, frequently confuse readers with sentences so ill-considered that their meaning is unclear or absent. Recent examples of both errors in online writing about Steinbeck’s greatest fiction can be found in a pair of blog posts published by two online magazines that, except for sectarianism and under-editing, couldn’t be less alike.

How Did The Forward Get John Steinbeck So Wrong?

The first post in question is by Aviya Kushner, the so-called language columnist of The Forward, a respected Jewish publication started in New York five years before Steinbeck was born. The “news flash from the distant land of real news” on offer in Kushner’s May 8 blog post—“How Did John Steinbeck and an Obama Staffer Get the Bible So Wrong?”—is the misspelling of timshol in East of Eden, old news to Steinbeck fans of all faiths or no faith at all. Kushner’s charge—that Steinbeck’s spelling error was an offense against language, culture, and morality—is undermined by her syntax. “It comes down to caring about language,” she writes in conclusion, “and insisting that words have meaning, which is, frankly, a hot contemporary topic that is not just political but also moral.” Ouch and double ouch.

Faith Is No Excuse When Blog Posts Make No Sense

The second example of online magazines writing badly about John Steinbeck comes from Pantheon, a site that bills itself as “a home for godly good writing,” apparently without irony. “Dreaming of Steinbeck’s Country”—the May 6 blog post by a self-identified minister named James Ford—means well but also proves that sententious praise, like captious criticism, collapses when style fails subject in sentences describing Steinbeck. “I consider the Grapes of Wrath [sic] one of the great novels of our American heritage,” writes Ford. “Currents of spirituality and spiritual quest together with a progressive if increasingly that agnostic form of Christianity feature prominently in Steinbeck’s writings. And no doubt it informs his masterwork the Grapes of Wrath.” [Sic] and [sic] again.

Is Your Piece Ready to Publish, or Does It Escape?

The lesson to be learned from this week’s examples of bad online writing? When blogging about John Steinbeck, take time to spell- and syntax- and grammar-check before posting. Online magazines have editors, but contributed posts are like the morning newspaper in Florida whose editor I once overheard describe this way: “Our paper isn’t published. It escapes.” Websites with a sectarian purpose, like The Forward and Pantheon, often make the mistake of allowing sentiment to overwhelm sense when publishing blog posts by sincere writers with a pro or con ax to grind. Steinbeck agonized over The Grapes of Wrath. East of Eden took years to write. Travels with Charley didn’t, and it shows. Is taking time to self-edit when writing about John Steinbeck for any website, secular or religious, asking too much?