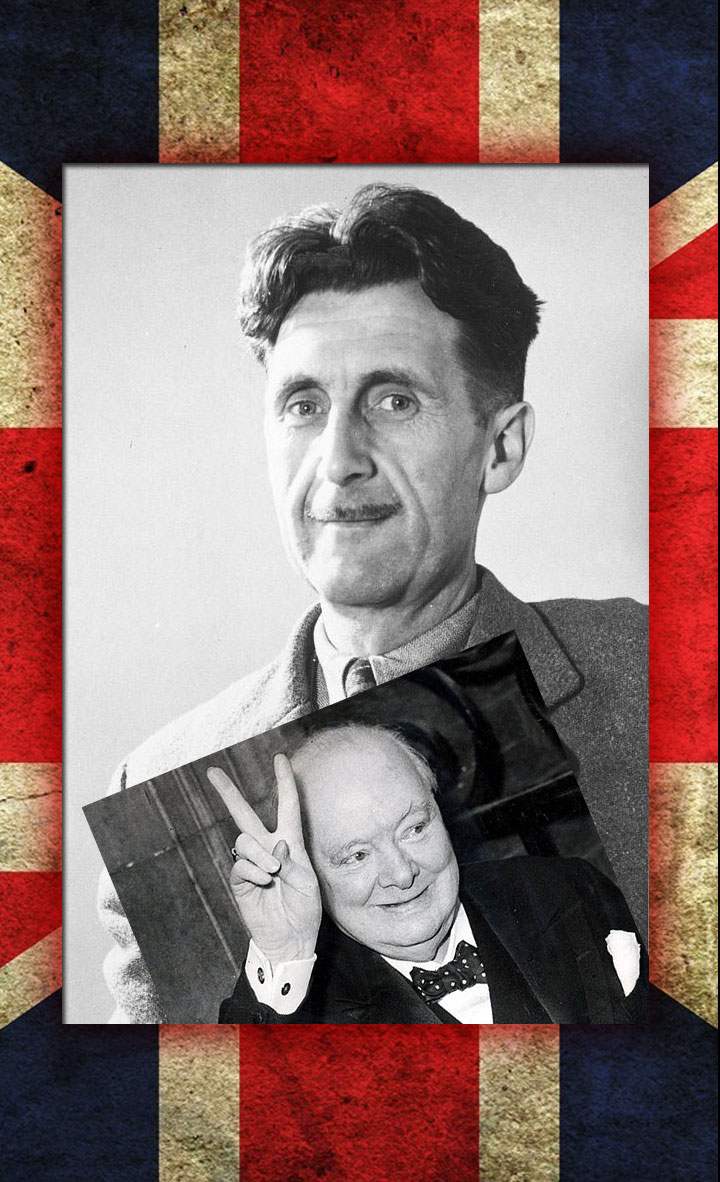

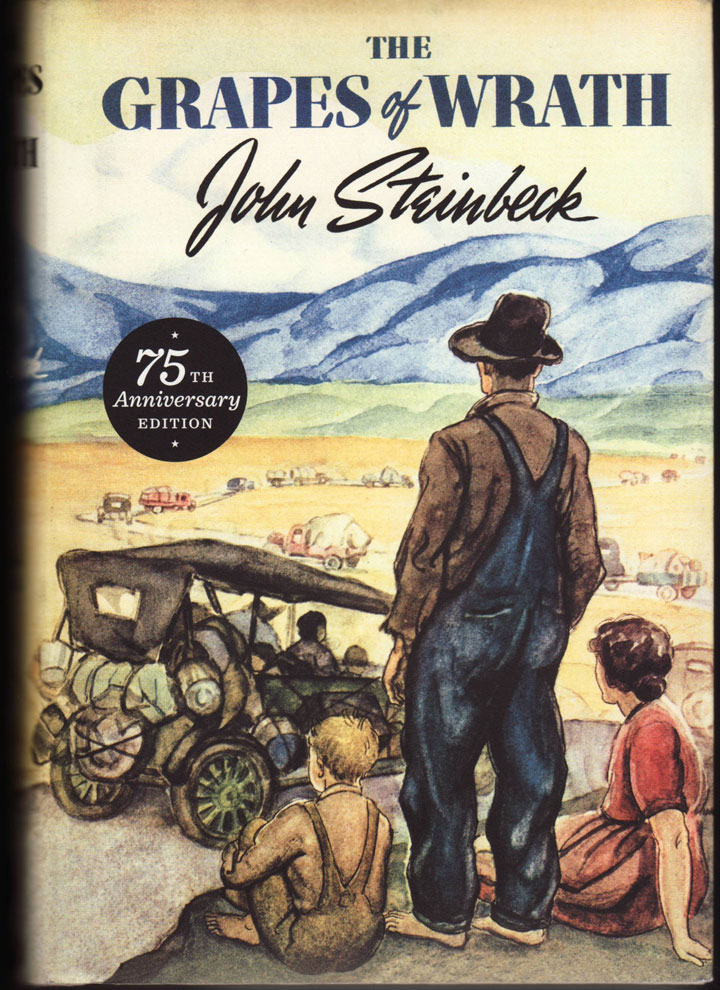

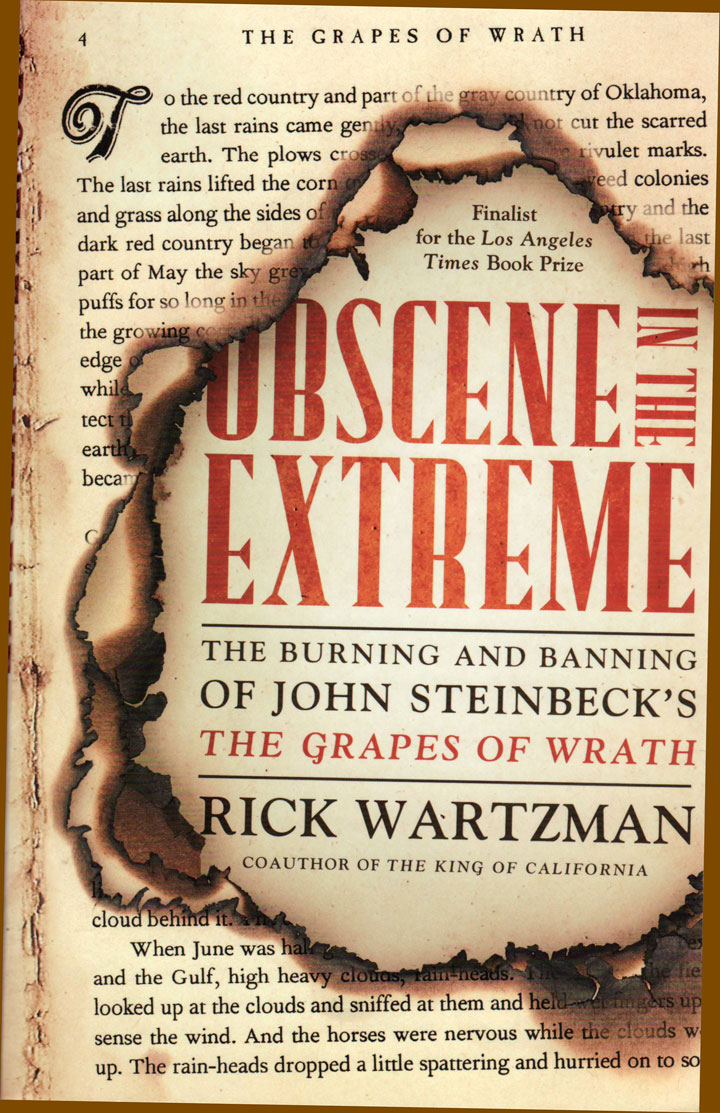

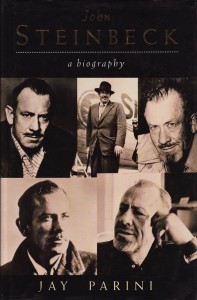

Winston Churchill is turning in his grave as George Orwell rejoices. John Steinbeck and other American authors, a group deeply disliked by George Orwell, are about to be dropped from Great Britain’s school curriculum. According to “Syal but no Steinbeck in English GSCE,” a BBC news report, English education bureaucrats expressed dismay at discovering that Of Mice and Men remains the most frequently read novel by British middle-school pupils. Henceforth, it is decreed, only British authors can be “taught-to-test” in government-supported schools throughout England, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

As an ex-English teacher and Anglophile, I have good cause for hating edicts by education bureaucrats, American or British. Here are 10 reasons why I despise this one with a passion:

1. Winston Churchill’s mother was an American, and America came to England’s aid in its darkest hour, inspired by Winston Churchill’s Anglo-American fortitude and friendship.

2. Most of my ancestors were English immigrants. My father, an Army corporal, was stationed in England. After the war my parents named my brother David Winston (for Winston Churchill, not George Orwell’s Winston Smith). I studied a pair of British authors for my PhD degree and consider George Orwell John Steinbeck’s equal as a writer, a compliment to George Orwell.

3. A disaffected Communist who disdained American authors and refused to visit the United States, George Orwell accused John Steinbeck of being a Soviet sympathizer as the Cold War heated up. Such calumny is to be expected from right-wing British authors who came, saw, and ranted—Evelyn Waugh, for example—but it’s unforgivable in a left-wing journalist like George Orwell who never crossed the Atlantic or questioned Steinbeck to find out for himself.

4. John Steinbeck loved and lauded England and had cherished English roots on his Dickson grandmother’s side. He was a war correspondent in London in 1943 and spent much of 1958 in Somerset, the period his widow Elaine said was the happiest time in their marriage.

5. Steinbeck mined British authors from Thomas Mallory to John Milton in his writing. Unlike George Orwell, he declined to criticize other American authors, at least in public, and as far as I know he gave George Orwell a pass when Orwell said nasty things about the United States.

6. Two classics by George Orwell will be spared in the impending purge of American authors, along with British authors considered too old-fashioned, from English schools; both George Orwell books—1984 and Animal Farm—continue to be taught in American schools, along with masterpieces by older British authors from Shakespeare to Dickens.

7. Winston Churchill, a world-class writer, understood the connection between what one reads and how one thinks. So did George Orwell, despite his parochialism. English students who never read Steinbeck will be as uninformed about the Dust Bowl and Depression as young Americans who never read British authors are about, say, Winston Churchill and World War II.

8. F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and Arthur Miller are also Out in English, Welsh, and Irish schools. Henceforth, ideas about America will come from Hollywood, hip hop, and other sources unpolluted by American authors. Future generations in Great Britain can be expected to care as little about our cultural heritage as most Americans care about that of England.

9. Instead, Sherlock Holmes and Meera Syal, the British screenwriter of Bollywood Carmen Live, are now In. This switch is the English equivalent of replacing American authors like Steinbeck and Faulkner with Jerry Seinfeld in American public schools.

10. AQA—the educational bureaucracy that wants to banish American authors from British schools—is short for “Assessment and Qualifications Alliance.” The English equivalent of our SAT Educational Testing Service, the organization frames its ponderous pronouncements in the educational equivalent of George Orwell’s Doublespeak, a sin against meaning in every sense of the word.

In my court, that last offense may be the worst. If you can’t express yourself as clearly as Winston Churchill or George Orwell, you probably aren’t thinking straight. Notwithstanding those British authors unmolested by the ACA, the bureaucrats in Manchester aren’t qualified to banish American authors from any country, least of all Winston Churchill’s glorious land.

Readers are encouraged to submit their own reasons to dislike the idea of dropping John Steinbeck and other American authors from schools in Great Britain. Personal or professional, silly or same—feel free to express your opinion in the Comment space below.