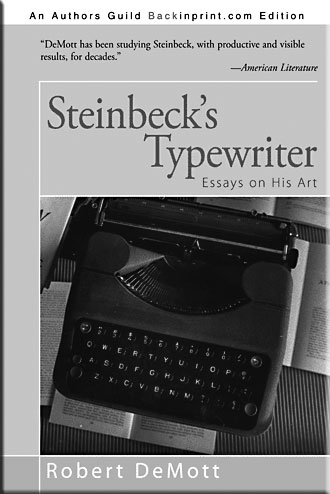

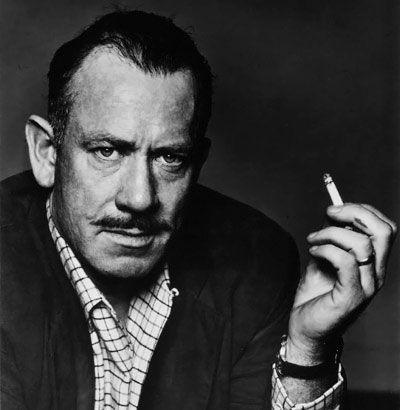

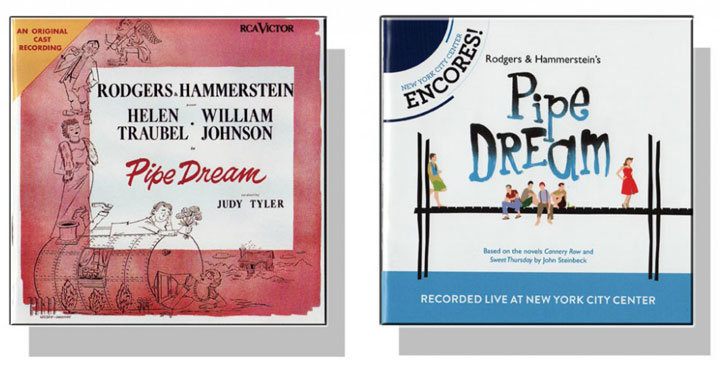

What made Pipe Dream, the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical version of Steinbeck’s novel Sweet Thursday, a failure on the stage? The 1955 theatrical production had a great source, a great team, and great prospects. It also had a run of bad luck, closing after six months despite record advance single-ticket sales, respectable group sales, and nine Tony Award nominations. I love Steinbeck and I love Rodgers and Hammerstein, but I’ll admit I never heard of Pipe Dream until I read Bob DeMott’s introduction to the 2008 Penguin edition of Sweet Thursday, the 1954 sequel to Cannery Row written by Steinbeck with Broadway in mind. I ordered the cast-recording CD, played the piano-solo version, and (I think) discovered the problem behind the problem with Pipe Dream.

Why Rodgers and Hammerstein and Not Frank Loesser?

Why Rodgers and Hammerstein and Not Frank Loesser?

Cy Feuer and Ernie Martin, the show’s producers, wanted Frank Loesser to write the music and lyrics for Steinbeck’s off-key love story about Doc, a deeply melancholy marine biologist based on Ed Ricketts, and Suzy, the whore who steals the heart of Fauna, madam of Cannery Row’s Bear Flag brothel. Loesser was a logical choice. The winner of two Tony Awards for Guys and Dolls, he had been part of Steinbeck’s inner circle. If he wasn’t nervous about glamorizing Damon Runyon’s downtown gangsters and molls, he certainly wouldn’t worry about an off-the-wall romance set in a California whorehouse. Unfortunately, the Loesser of Two Goods was already working on his next hit, Most Happy Fella. But Rodgers and Hammerstein—the Greater of Two Goods, judging by Broadway’s bottom-line standard—were willing, available, and friends of the Steinbecks. Strike one.

Feuer and Martin also wanted Henry Fonda for the role of Doc, the troubled male lead in Pipe Dream. A 1940 Academy Award nominee for his portrayal of Tom Joad in The Grapes of Wrath, Fonda had won a Tony Award in 1948 for his performance in Joshua Logan’s Broadway musical Mister Roberts. Fonda was also Steinbeck’s friend. Unfortunately, his singing voice wasn’t acceptable to Rodgers and Hammerstein and a less experienced performer got the part. Strike two.

For the demanding role of Fauna, Rodgers and Hammerstein were determined to have Helen Traubel, a classical singer whose Metropolitan Opera contract hadn’t been renewed because Rudolph Bing, the Met’s imperious manager, didn’t like her moonlighting as a nightclub singer. Hammerstein heard Traubel perform at the Copacabana club in New York and later in Las Vegas, where he offered her the part of Fauna in Pipe Dream. Honest about her lack of acting experience, Traubel accepted Hammerstein’s offer anyway. Strike three.

Odds in Favor of a Rodgers and Hammerstein Success

Odds in Favor of a Rodgers and Hammerstein Success

Yet the odds in favor of another Rodgers and Hammerstein success were strong. Oklahoma!, the pair’s first Broadway collaboration, ran for 2,212 performances after opening in 1943. Carousel—a tender story that touched the taboo of domestic violence—ran for almost 900 performances starting in 1945. But South Pacific was the Rodgers and Hammerstein home run that played for years, proving the team’s staying power. Co-written with Logan, Hammerstein’s book openly treated racism, also off-limits for Broadway musicals of the time. Rodgers’ timeless tunes were performed by Ezio Pinza, a classical musician who (unlike Helen Traubel) could act as well as sing.

There were modest failures for Rodgers and Hammerstein along the way, but not many. Allegro opened in 1947 and lasted only nine months. A serious work with a heavy moral, it had a Greek chorus, no sets, and direction and choreography by Agnes de Mille. Me and Juliet—the story of a backstage romance involving an assistant stage manager, a chorus girl, and her electrician boyfriend—featured complex machinery and lighting in place of standard sets and props. Though the odds in 1955 favored Pipe Dream, there was precedent for failure with Rodgers and Hammerstein. Allegro and Me and Juliet, shows that took a bet on breaking rules, had good music and short runs. Two of these traits would also characterize Pipe Dream.

Why Did Hammerstein Sentimentalize Steinbeck’s Story?

Why Did Hammerstein Sentimentalize Steinbeck’s Story?

Following not breaking Broadway rules proved to be the problem with Pipe Dream when it opened. Steinbeck closely observed the process of production and worried that Hammerstein was making a mistake in fudging the character of Suzy, the female lead. Described by Steinbeck in a letter to Hammerstein as “an ill-tempered little hooker who isn’t even very good at that,” Suzy had to be a whore, Steinbeck said, for Pipe Dream to work as drama. Fauna’s Bear Flag establishment—in Steinbeck’s novel, the best little whorehouse in Monterey—was becoming a Hallmark card in Hammerstein’s timid treatment of Steinbeck’s tough story. Worse yet, Richard Rodgers was hospitalized with cancer during rehearsals for Pipe Dream, leaving Steinbeck alone to lose his argument with Hammerstein about how much reality audiences were ready to accept regarding Suzy’s true vocation and Fauna’s business. Strike four.

Yet from the show’s overture to its reprise, the music for Pipe Dream is Richard Rodgers at his best. “All at Once You Love Her,” “Everybody’s Got a Home But Me,” “Suzy Is a Good Thing,” “The Man I Used To Be,” “Sweet Thursday,” “The Next Time It Happens”—the show’s songs are as good as Carousel or Oklahoma! despite a single, significant exception. Hammerstein’s reluctance to reveal the truth about Suzy and the Bear Flag is evident in the words and music of Fauna’s signature song, “The Happiest House on the Block.”

I’ve played it a dozen times. Is the Bear Flag’s proud proprietress singing about an all-night whorehouse with a heart or a Hallmark household that simply stays up later than the neighbors? Major key or minor key? Comedy or kitsch? Like Hammerstein’s words, Rodgers’ music can’t quite decide which, leaving this listener—and audiences—confused. Steinbeck was right about Suzy. For anyone to care, she had to be a whore, not the virginal vagrant created by Hammerstein and derided by Steinbeck as coming across like a visiting nurse. And the Bear Flag had to be a brothel, not a house party with a happy-you’re-here message.

If Only Stephen Sondheim Had Staged Pipe Dream Instead

If Only Stephen Sondheim Had Staged Pipe Dream Instead

Sometimes serendipity comes in small packages. While I was thinking about what happened to Pipe Dream between Sweet Thursday and opening night, I received a DVD of the TV special, Broadway Musicals: A Jewish Legacy, for contributing to my local PBS affiliate. There I learned the startling reason Hammerstein was so wary about Suzy, Steinbeck’s whore—and why Stephen Sondheim would have been a better choice to stage Steinbeck’s ironic story 60 years ago. I’d always assumed that Hammerstein—like Stephen Sondheim and other social outsiders who created the Broadway I loved more than life—was Jewish. I was wrong.

Although his grandfather was a first-generation impresario on the pre-Broadway Jewish stage, Oscar Greeley Clendenning Hammerstein II was reared as an assimilated, Anglicized Protestant. And though Stephen Sondheim became Hammerstein’s greatest protégé before the composer died, Sondheim remarks on the DVD that he always resented Broadway’s genteel, Gentile habit of avoiding ambivalence by forcing happy endings on unhappy realities. From the Stephen Sondheim point of view (also mine), a Suzy without her profession, a Doc without his darkness, a Monterey without its whorehouse are monochromatic monads devoid of drama: Oklahoma without the Joads— Oklahoma! without The Grapes of Wrath.

Within years of Pipe Dream, Stephen Sondheim liberated Broadway from its remaining taboos: ambiguous sexuality, ambivalent relationships, and fear of 3/4 time sustained without let-up in a show. Too late, too bad, and a bit haunting when you imagine what might have been if Hammerstein had been as brave as his pupil and less attached to his class when writing Pipe Dream. Like Steinbeck, the lyricist of South Pacific and The King and I was a political progressive with a social conscience. Unlike Steinbeck—or Stephen Sondheim—he never abandoned his Middle-American devotion to happy endings and keeping up appearances. Other than not being Jewish, I wonder why he couldn’t make the leap. Perhaps because—unlike John Steinbeck and Stephen Sondheim—Oscar Hammerstein was a better-socialized product of a better-adjusted childhood with less reason to rebel, reject, or revolt.

In his closing interview for Broadway Musicals: A Jewish Legacy, the director-producer Hal Prince reinforced my thoughts about Oscar Hammerstein’s timidity. Prince recalled that when he read Kander and Ebb’s original treatment for Christopher Isherwood’s “Goodbye to Berlin,” he thought their concept was too old-fashioned and added a sexually ambiguous character with the anonymous name Emcee. The show became Cabaret, Joel Grey became famous, and it was 1965—10 years after Pipe Dream and less than a decade before Stephen Sondheim replaced Rodgers and Hammerstein as monarch of the Broadway musical. I hope that John and Elaine Steinbeck saw Cabaret when it opened. I wonder if either imagined what might have been if Pipe Dream had been staged by Hal Prince or Stephen Sondheim.