James Dean was driving his new Porsche to a car race when he crashed—literally East of Eden—on a back road to Salinas, California, site of the 1955 movie that made him famous and the weekend event that made him dead. Sixty years later, Roy Bentley ponders the irony of Dean’s death and its aftermath in a poem that suits the East of Eden star to a made-in-China T.

James Dean Commemorative Mug

I’d begin with the stamped instruction not to microwave

and the all-caps MADE IN CHINA messaging,

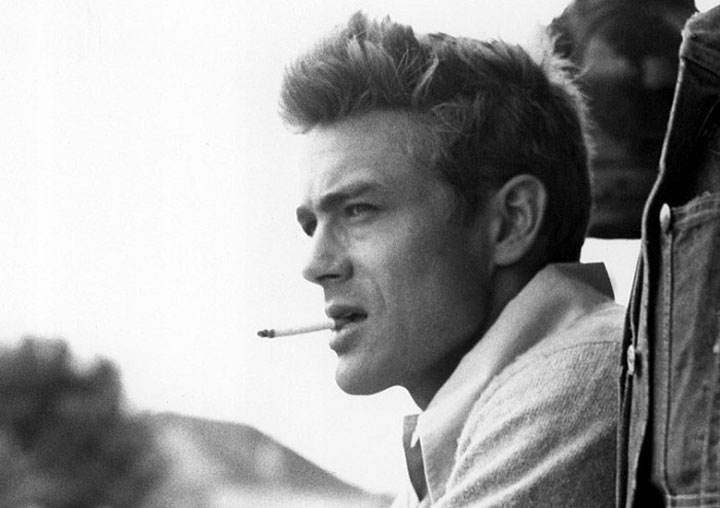

the glaze over the decal of the brooding movie star

who shot a Public Service Announcement

for safe driving then ended up a traffic statistic.

The cup makes me ask what else is detritus

bobbing against the current. Holding the gift-mug,

I consider the difference between the doomed—

those who climb into the Spyder Porsche death car

with a wish to flame to ash—and the vanishing

and coming back to vanish at last that is a life. Time

is cenotaph and memorial for a soil scent

that rises, post-rainfall, in the dark before morning

on summer farms in Salinas, California—

the image on the mug is from East of Eden, Dean

in a sweater on a boxcar roof, huddled,

shivering against the chill. Because, face it,

when are we ever in the right clothes?