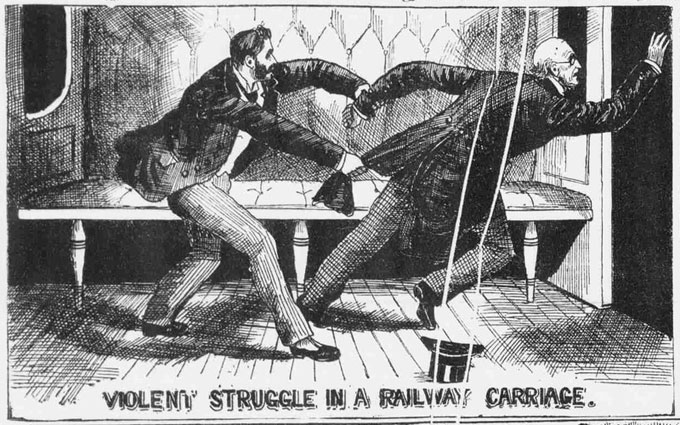

The Victorian Belief That a Train Ride

Could Cause Instant Insanity

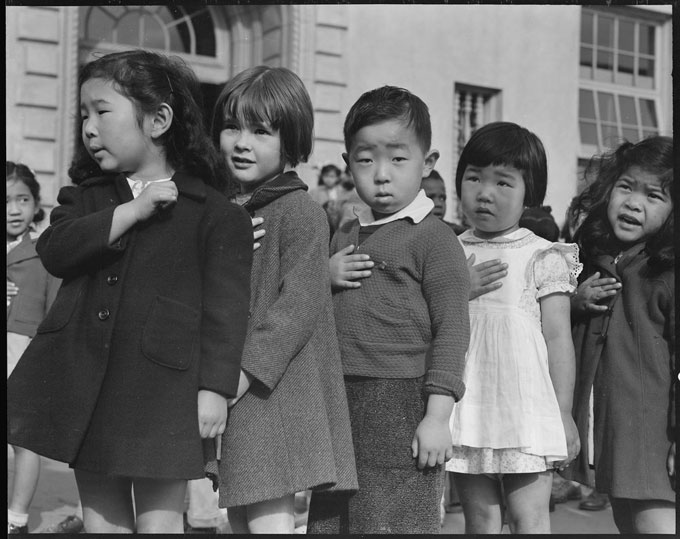

Somewhere in Appalachia, a woman

is telling her oldest son not to strike back

at a fugitive father for having abandoned them.

The standard unit of pain is hers to call whatever

she wants since she wears the bruises like the son

wears Goodwill Levis and a t-shirt saying Tramps

Like Us, Baby, We Were Born to Run. The son isn’t

showcasing what he is, in his father’s cast-off t-shirt,

because Springsteen is the last word in Suffering. He

puts it on, the t-shirt, because what changes the way

we breathe is what we believe—though the Victorians

believed train rides could drive you mad. The riders

were rescuing themselves from the insanity of others

just by boarding. Just now, this one knots his leather-

and-scrap-wood tchotchke crucifix around his neck—

the cross is hollow and carries a powder they say

will kill you. I say what kills you isn’t the drug but

the hopelessness puts it there. Saying that, though,

is like floating on the wind through sainted hillsides

where row-house chimneys are censers distributing

God’s breath as coal smoke. The smoke is bruised

gold. It says how, even if there is no God and all

the days from Then to Now have handed us no

reason to hope, we still have a train to catch.

Inspired by an Atlas Obscura item linking Victorian-era train rides and mental illness.