Railroad Depot at Fleming, Kentucky: November, 1915

It would have been a gunmetal gray rail line for snakes

to cross but no snake visible. It would have been beautiful,

the cloud-veil of locomotive breath. And starlight-struck.

Behind the depot: laurel thickets. A sign for horse feed.

Denuded limbs would gray the hills, the shadow train

in the right of way speeding alongside an actual train.

There’s horizon, and there’s red-poppy-colored light

on the platform, and a man would have patted a pocket

of his overalls for the fresh tin of Prince Albert tobacco.

I want to hold title to those rich acres in the bottomland

and I want no one to hold title to it but for wildflowers

to grow at the side of a wagon-furrowed road. I want

to watch my dear dead waltz into Paradise, spirit-

heads high, setting aside histories as they commence

stepping off distances to build houses. Towns. Cities.

In 100 years these may talk the pace of human rights

and Snow on the Mountain Fall Blooming Camellia

as a symbol of expectation in To Kill a Mockingbird.

Today, the locomotive is taking on water. Its engineer

slouches. Maybe he smells wood or coal smoke or both.

See other men rising to their full heights. Hear the voices

separate extant pain from the gorgeously swaddled world.

See the white-haired man with the scratched, blue suitcase.

Each of these has felt one recent grief fresh upon waking.

Gloryland Effect

My grandmother Potter said her son Earl died from a gunshot wound.

Said that Johnny Belcher had shot him—Earl—in a bar in Kentucky.

She showed me the 8 x 10 of Earl in army uniform, visor cap cocked

on his head, the cap more than broken in with wear on parade grounds

and on leave after battles, a glow about his handsome long-dead face.

She called that sepia glow the Gloryland Effect. I was falling asleep

the first time she handed me the photograph, and I dreamed of him,

my murdered uncle who read Zane Grey and fathered children

before a single bullet in his liver ended his dreams, if he had any.

I dreamed of him in a place I supposed was heaven or the Afterlife.

In one of those whispers for which the dead in dreams are famous,

he said I should be careful growing up. Said I should love her for him,

my grandmother, his mother with a wide center part in her gray hair.

And I woke with that 8 x 10 vanished into her Samsonite suitcase.

I called her and she came to me, having traveled at the speed of love

after many losses; some great, some less so. She spoke and I knew

each of us has a glowing soul of which we never stop speaking.

Members of the Primitive Baptist Church

Attend a Creek Baptism by Submersion

The line of worshipers collects by an August creek bank.

Their song goes Shall we gather at the river, the beautiful

the beautiful river . . . The creek isn’t much during summer,

though it will all but cover a convert to his or her waist.

A woman in white is holding a man’s fedora. Another

is wading out from the bank into russet-colored water.

Frances Collier Potter is here, hair bobby-pinned up.

In epistolary First Corinthians, the Apostle Paul says

that the hair of any woman is her glory and covering.

Her pastor says it says that. Adds salvation is no joke.

If it is a joke, grace, the punchline is accepting Christ

with the faith of a child: meaning as blindly trusting

as anyone, male or female, gets in Letcher County.

Ask anyone about Letcher County and you’ll hear

that if God plays favorites, this isn’t one of those.

Ask about the Redeemer any time but don’t ask

Frances Collier Potter about a child she lowered

into black as familiar as the slap from a brother

or husband. In the fish-slaughtering coal mine

run-off, closer to an understanding of laurels

than the supernatural, she lets go the memory

of star thistles of frost on glass after the death.

Even if it’s true that good moonshine covers

a multitude of sins, this is the wrong woman

to fuck with. Glory or no glory, she hikes up

her cotton robes and goes in to put one eye

to the task of keyholing the door to mercy.

The Universe as Drunk Girlfriend

Unchecked, she opens an event horizon of a mouth

and out it comes: the turd-in-the-punchbowl analogy

disbursing both the n-word and a sexual metaphor

involving black holes. Occasionally, a side boob

will tease in the way that the God particle does—

dancing a waltz with Mind, a roiling tango. Maybe

the reason that suffering surrounds her has to do

with a mother dropping dead in an airport in Ohio

and then a father running off with a plate-spinner

who performed before The Beatles on Ed Sullivan.

Singularities and space-time rifts were born in her,

though her singular nature comes with firecrackers.

Matches with archangels on the matchbook cover.

Though there are no instructions in any language,

there are some who say the fuse is labeled After

lighting, run. If there is Spirit, hers dances—

with or without a partner and music. Hearts

like hers stagger around backstage at rehearsals

waiting for the next big bang-boom. A beauty,

she is some piece of work. Remember the time

she ran over that dog, then asked you to get out

and see just what sort of damage she had done?

Remember how much you loved her, her mystery

and how, in her wake, it collected as pockets of

absence? Lately, they say she travels with a cat.

A fat tabby she’s named The Strength of Lies.

The animal is reportedly fond of starscapes.

Huckleberry Finn Wanders into Westeros

I was 17 and three days a runaway when I stole Life

on the Mississippi from Becky Thatcher’s Bookstore

on North Main Street in Hannibal, Missouri. The spine

of a Penguin paperback read New American Library.

Outside, it was a blue-sky May afternoon and I was

an hour too late to be admitted to the home of Sam

Clemens’ childhood sweetheart, Laura Hawkins.

All right, 40 years later I’m at Lefty’s Tavern

near the Jersey Shore. Checking voicemails.

And I want to hear above the Game of Thrones-

themed wedding they’re hosting. Third playback,

I hear Results came back negative. No cancer.

And I order a Rebel IPA. Toast the revelers.

If Jorah Mormont is battling greyscale carriers,

stonemen, his best man the dwarf Tyrion Lannister

dodging death by a thousand cuts from paper swords,

it isn’t on the Mississippi. And if Huck and Jim put in

anywhere in Westeros, Jim gets beheaded or lynched,

left to twist as a species of strange, unspecified fruit.

But at Lefty’s Tavern, the news is all good. A bride-

as-Daenerys-Targaryen, cleavaged, three firedrakes

in attendance by a spray of long-stemmed red roses,

is trying to shoplift bliss, the new American variety.

In that story, a queen walks dragon eggs from fire

and a knight-protector is mesmerized forever after,

a runaway slaver risen from the ashes of disgrace.

In make-believe, all ravens are starlight-throated;

in Barnegat, you steal cable and park a Cadillac

on cinderblocks behind Lefty’s. Fantastic is as

fantastic does. If the body is a raft, then those

borne along on it rate at least one dragon egg

above a drone of messages it’s hard to hear.

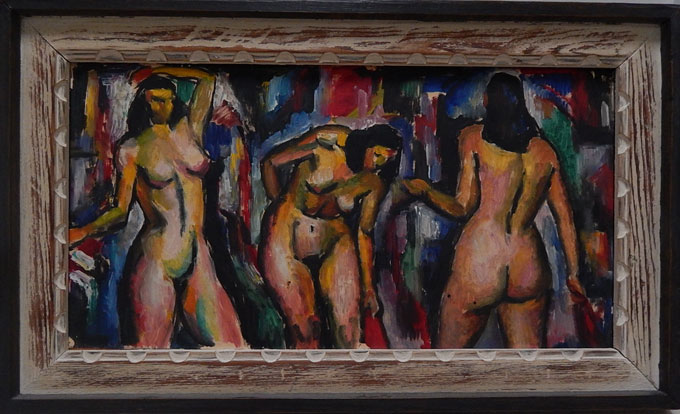

“October Piece” (1969), the illustrative image evoking John Steinbeck’s California boyhood and Roy Bentley’s memory of a train depot in Kentucky, is a popular print by the critically acclaimed contemporary American artist Peter Milton.—Ed.