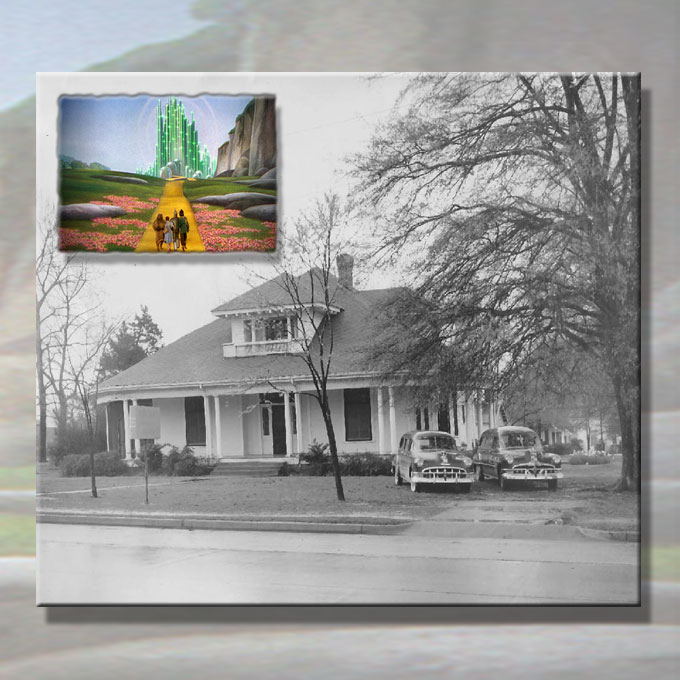

Easy Rider

An ache that I was in those days waited in line

so 1969 might tie a red-white-and-blue ribbon

around the adolescent hard-on I was sporting.

My country as first love. Something like that.

I read Dennis Hopper ordered four police bikes;

had each of them painted to stand for Freedom

and giving the raised middle finger to America;

one Old Glory on wheels, one to say that flames

are forever, the trumpet-notes of Harley exhaust

soundtrack for a story of outlaws about to accept

the sword of the fucked world through the heart.

After sitting through the movie, I felt changed—

like one of those police bikes which were later

ripped off, vanished into silver-screen legend.

I’d say it, the film, made me ache for the self

to be thieved from the best of the road ahead

if the road can be right after getting you lost

in the South with long hair and a death wish.