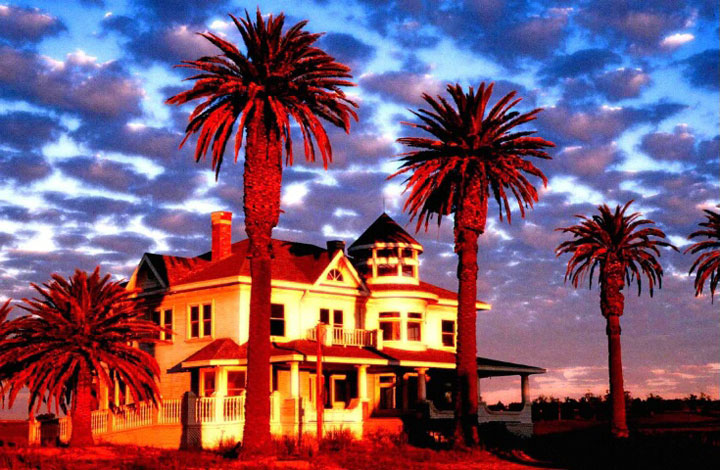

After a Great Wind

In the too-early darkness, candlelight flickered

our shadows up the stairs. Beneath open windows

we lay bare, sweating between sheets and dreams.

Transformers exploded in fireballs. The storm

peeled roofs like lids of tinned sardines. We lost

homes beneath old oaks and shallow maples.

We wake to a wounded city. Empty refrigerators.

Eat raw. Board up what we must. Make our way

through a jungle-green maze of limb and canopy.

Together we heave lighter branches to the curbs,

toss in twigs. Tree trunks that crushed our cars

we leave for huge machines to grind the wood,

spit sawdust. Cautiously we move, and watch

for the power lines’ fanged bite. After sundown

we lie uneasy, to sleep, day animals in the night.