It had rained. The hillside was a black enormity both sides of the road as if the world had lost its color or dissolving objects had become apparitions and blurred into one another.

We had never been close, my brother and me, standing apart even in family photographs, but he rescued me from prison at the last possible moment by having me committed. What had I done? The misdemeanor offense of aiming and firing at a man. All right, I ran a man who shall remain nameless up a telephone pole with a .45 that I carried in my pocketbook—there were black bears in that part of the state and randy bootleggers loose in the night. I might have felt kindly toward TW, but I was thinking of Daddy and his locking me in a closet for three days.

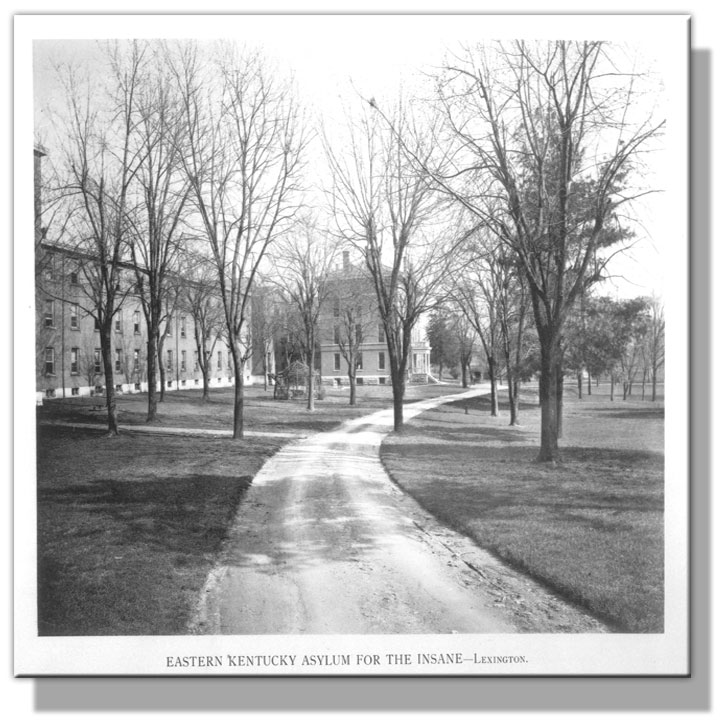

It was one of those damp days in fall, everything a shade of gray. I was on leave from Eastern State Hospital, known as Kentucky Asylum for the Insane before 1913. My brother TW thought I should be at the funeral of our father, Quentin Wolff, who had burned to death in a field fire. TW had signed me out on furlough and was driving me to Neon from Lexington in a 1930 Model A Ford I recognized as one Daddy gave me to use for my eggs and butter route.

Shock treatments my brother signed off on at Eastern left me seething. And “seething” is putting it mildly. If I had tried to kill someone who got me in the family way and then wouldn’t leave his wife and children—if I had emptied an entire clip of store-bought ammunition at Nameless as he scurried up a phone pole, what might TW and the rest of eastern Kentucky imagine I would want to do next? TW seemed wary. He kept looking over in my direction. He acted like he had something he wanted to say. He looked changed from the last time I’d seen him: a fletching of gray at the temples, lace-like lines around the eyes. He always wore a kind of uniform: white shirt, suspenders, wingtip shoes, a suit jacket. His feelings for Daddy were what I’d call a grieving love. 1940 could have been a tough year for him already for all I knew.

My brother said, You look nice in that dress. Gray suits you.

I don’t want to talk, I said. I’m not mad. I just don’t want to talk.

TW looked over at me then back down the road. His expression hadn’t changed.

That’s all right, he said. Save me having to talk about the weather.

When I was growing up, my folks would talk about the hostilities that tore Kentucky apart in the Civil War. My granny taught me the phrase The War of Northern Aggression. I’ve heard the North wasn’t the aggressor and that the South was defending its right to own and trade slaves. This was like that, a white lie. TW saying I looked nice. What you hear in place of something it was understood you had spared the hearer. I’d been cooped up for three years in an institution whose saving grace was that it wasn’t Kentucky State Women’s Prison.

I wanted to believe the shock treatments were necessary. If I closed my eyes I could see attendants standing over me before the air turned gold then blue-black and I went unconscious and woke to see the matron in charge—Hazel Lynch—with her black hair pulled back tight. I’d see her giving orders with the carriage of one used to taking charge of others. I’d see an orderly wiping up something. Riding in a car that had been mine, I had to tamp down my rage. Nothing about what had happened was fair, but where in the black and white world was there a house where what happened was fair? I was helpless in the face of the consequences of my one very-visible act of aggression against the world of men. I was never demure, never girly, but I was learning what it takes not to call attention to oneself. I held my hands folded in my lap.

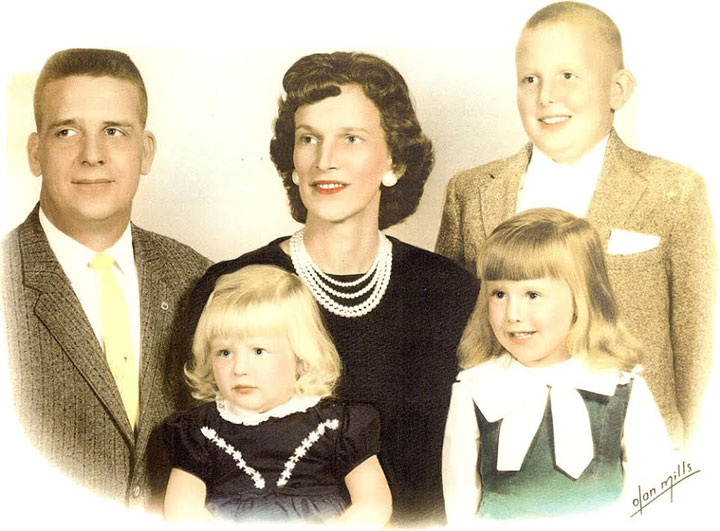

If you were to look at old photographs of my brother Thomas William Wolff at medical school in Lexington: Errol Flynn. All movie stars look crazy, but especially Flynn. Others whispered TW had the world by the tail, but I saw the fear. His pencil-thin moustache was part of a mask. I knew he was terrified he might crack up or become a man who buries money in a Maxwell House coffee can in the backyard then forgets where he buried it—like Daddy.

Before my commitment I prided myself on dressing in store-bought clothing and a few fine accessories that won me notice if not compliments. I had been the captain of my own ship—a canary-in-the-coal-mine Model A—and I had seen what dressing well could lead to. I had money and a smile on my face. I was someone others said hello to. I wasn’t someone about to crack up and need to be put away. That is, until ol’ Nameless Married Someone noticed me.

I delivered eggs and milk and butter then. His neighbor Joe Samuelson was on my route. The first time our eyes met—on the stoop at the Samuelson place—Nameless looked at me like he couldn’t face a day without me in it. I was important to someone. Which was what I’d heard I was on the earth for. I’d been married. I knew. That didn’t mean he didn’t take advantage of me. He did. Three times he caught me alone and tried to force me, three times I said no. The fourth time he cornered me. It was night. We were outside. Stars wheeled overhead, the spaces between stars a sullen web. What was happening—it was like the color was being drained from the world.

A few months after, Daddy locked me in a closet. He had gone into Neon and someone had asked him if I had taken up with a married man and “gotten in trouble.” It was the first Daddy had heard of me and Nameless. Maybe the first time he had thought of me as having sex and being someone men might want to have sex with. I’d been married, had two children, but this was something else. I was under his roof. He was responsible for me.

The closet might have been all right, bearable, but after I went to the toilet in the slop jar he had allowed me, I started vomiting. That made it, that confined space, take on a woozy stench.

I didn’t eat for three lost days. When he finally threw open the door, Daddy didn’t say anything. Didn’t apologize. I went and drew water. Boiled it. I bathed. Dressed in other clothes. I had found flour to make biscuits and was in the middle of rolling the biscuits when Daddy came in. I had looked down at dough I was rolling and so didn’t see him raise his hand.

He hit me with his fist. I know I lost consciousness because, when I woke, I was lying on a bed of feed sacks on the porch where I’d been dragged and left.

I made up my mind that someone was going to pay. If not Daddy, someone.

When I fired the pistol at Nameless, I was smelling that foul closet and seeing the last pieces of the light become an inverted delta and disappear in that space as the door closed.

TW didn’t smoke or chew, didn’t swear unless it was something he did out of everyone’s hearing, so he would have been designated a moderate man. A man who other men knew could be trusted with their secrets or their money. But I knew TW had a couple of women up in the hollows. You wouldn’t have known it to look at him, but he was something of a ladies man.

As he drove, and the black-tree-miles passed by on either side of the Model A, I thought of one mountain woman named Beth Stallard. Beth was a quilter renowned in the mountains for her skill. The rose pattern in the quilt on floor of the front seat was likely hers. The fact that it rested where it did wasn’t an indication of anything, but I thought it signaled some fondness. The quilt—like Beth—referenced the mysteries of a man who stood apart from others in and around this part of Letcher County. There was a flame juggler prancing on the roof of a house. A Stars & Bars and a crucified Jesus. I reached to the floor for the quilt.

You cold? TW asked.

He looked back at the road as I unfolded the keepsake quilt. It presented as a rising sun on a field of patchwork clouds. It had a star-strewn, black square in the foreground that reminded me of Hazel Lynch’s hair and of the trees at the side of the road. Black was, I thought, an odd color to plant front and center like that. Morbid, to some eyes. Tacked to the sky in another square was a rainbow above a Christ-on-the-cross. Ravens crossed the respective squares, streaming into the assumed air like black water. I smoothed the quilt across my lap then sat and rubbed the place between my thumb and forefinger on my left hand and rocked.

Sometimes I think too much, I said.

I don’t think enough, he said. I know.

I’m glad you’re here.

He started to say something else. Thought better of it. Sighed.We drove on. I counted the embroidered ravens on the quilt as I rubbed my hand.

It was the third year of my hospitalization. I had been married and divorced. My three children had been taken from me. I was a stranger to them now. If I wasn’t a conversational companion, I thought I’d earned some understanding. I knew my anger was a cloud between us.

And the way TW strained to see landmarks ahead, it had nothing to do with landmarks.

He opened the ashtray. Took out a pack of Camels. Tapped one into his mouth and lit it. In a moment he cranked his window down.

I can stop at a diner I know up ahead, he said. If you want.

I knew he wouldn’t offer me a cigarette since he likely recalled I didn’t smoke. Smoking was not among my vices, not yet, but I liked the smell. I liked that it reminded me that the air around some men is poisonous. There were few other cars traveling the road my brother and I had been on now for a little while. It might be nice to have a slice of pie. Apple. Maybe a dollop of vanilla ice cream. I told him to stop. Which seemed to please him. He flipped the lit cigarette out the window, blew the smoke out the opening, then cranked the window back up. I had the quilt across my lap, but I said what I said not caring whether I might be thought odd or crazy.

TW had my future in his hands. A furlough was what he called this leave from treatment.

He would decide how long I had on the outside of Eastern’s red colonial walls.

Leave the window down, I said. I might like some air.

After the diner, we drove. The air brightened. The trees changed colors. Black became forest green. Shadows flew. Maybe I did need a slice of Bluegrass State apple pie a la mode.

I didn’t remember the trip to Lexington taking this long, but I’d been in handcuffs and in a different car, a sedan, and a state of mind that doesn’t allow for close observation of distances and time. Ravens like those on the quilt had been in the impossibly blue sky as I stared out the window of a sheriff’s car. I remembered wings. Blue-black wings. Snow either side of the road. The smell of men in the front seat smoking cigarettes. That day, I remembered looking down at myself at some point during the ride and noticing that my skirt had ridden up and no one had smoothed it down. This was a different day. The birds in the air weren’t circling or sending messages to one another in some language known only to birds. This was the day that the crazy woman in the yellow Model A had lost her father. Today I could watch and listen to the birds without worry that they were betraying secrets. I could smooth down my own skirt. I could ask for, and be handed, a wedge of warm pie with a mini-mountain of vanilla ice cream on top.

* * *

I wasn’t sure how long I had been asleep. TW was smoking a cigarette. Driving. He looked in my direction then back out the windshield and down the road.

You been asleep about an hour, he said.

How much farther?

Not far.

I fell back asleep and dreamed of Eastern State. Its orchards and ornamental trees. The trees became attendants grabbing hold of me to drag me to a room for another session with the electric-shock machine. This time, in the dream, someone was saying According to E.A. Bennett 90% of cases of severe depression which are resistant to all treatments will disappear after three or four weeks of ECT. The words of the sentence remained now after the therapy had wiped away my memories, though they came rushing back first as dreams then as nightmares.

When I awoke again, the car was stopped and TW absent from the driver’s seat.

Judging by a winged-horse swinging sign on a post outside, we were at a gas station. I heard a laugh then TW was by the driver’s-side door and then the door opened.

I had to stop, he said. I was running on fumes.

The quilt had slid onto the floor. I picked it up and spread across me once more.

TW said, You like that, don’t you.

There were other cars on the road. One driver honked. Waved at a car driven by someone with flame-red hair. A woman, judging by the lipstick-red smile. The woman waved back.

TW pulled out onto the road again.

We should be there in an hour or so, if I don’t get behind another coal truck.

On Sunday?

TW looked at me. This is Thursday, he said.

I felt myself looking at my brother. I saw him now as something other than the boy-man who came back from medical school with a lightness to his step and a smile and a good word for everyone. His face seemed sadder. The lines had deepened. At the temples his wire-rimmed spectacles had worn a thin line of green in the gray, close-cropped hair. A patina. He had taken off his glasses in the diner and I had noticed it then, but now I could plainly see green against the gray. Like one of the doctors at Eastern named Gragg who coughed between endless cigarettes.

TW began speaking. He said, We can drive straight to the funeral home. Or we can just go the house—the new brick house. You haven’t seen my house, have you? Let’s do that.

I didn’t know how to answer. I wasn’t sure I wanted to be made to see Daddy. Especially since he’d died by fire. I imagined his body—seeing it—might cause me to get upset. It didn’t occur to me to consider that the casket might be closed.

I said, I would like to see my boy.

Is that what you want? I’m happy to do that. Molly is waiting to feed us—she may have it ready and on the table. You like ham, right?

The child in question was my bastard by Nameless. I had named him Charlie: Charles Leroy Wolff. TW had been “seeing after him”—his phrase those times he’d visited me in the years I’d been away. I wanted to try and add up the number of visits, but I couldn’t. Often when he had come, I’d been in restraints for an outburst or rule infraction and was so mad I forgot who was and wasn’t in the room. If I had to guess, I’d say he came to Eastern State Hospital twice a year: Christmas and Easter. Always with something for me to sign. And always after the holiday.

On one such visit TW asked me to sign over—deed—to him my portion and share of the bottomland-homestead forefathers had claimed when they came into the Big Sandy River Valley area with Daniel Boone before 1800. My arms had to be released from a strait jacket then massaged for me to be able to write. My brother waved to the attendants to make that happen.

He said he would bank my share. I would have what I needed out of the interest.

He’d manage the principal. Invest it.

I wasn’t sure TW had heard me. I was used to what I said being ignored or dismissed as the ravings of a mad woman. I said it again.

You can do that. And you will. But you have to behave.

We were turning onto the two-lane that I recognized as leading into Neon. There was the Ford dealership, a drugstore-soda fountain, the Bank of Neon, and The Neon, the town’s one theater. The marquee at The Neon advertised The Wizard of Oz. I had heard attendants talking about it. Someone said it was in color—of all things! They said it was a children’s movie.

I said, I’d like to take Charlie to The Neon. See that new movie.

His eyes turned from the road. We’ll see, he said.

The car was warm. I kicked off the quilt then thought better of that and scooped it up and folded it. I tucked the quilt into the place where I’d found it. The flame juggler stared out from the fold. The act of caring for the quilt seemed to meet with some approval on my brother’s part. He pulled the car up a brick drive to a level spot. Parked. I’ll get your suitcase, he said.

Should I bring the quilt inside, I asked, knowing who had made it.

No was all he said.

The house smelled of bread and something else. Maybe—pecan pie.

TW’s wife Molly greeted me with a hug and kind words. After my time in Eastern, I recognized kindness. If it had a color, I thought of kindness as blue. It was a Kentucky sky. Not the pewter skies above the snaking two-lanes. Not the salt-colored smoke TW blew out the window of a yellow Ford. Not the sentinel gray-then-black-then-gray confederacy of trees on the grounds of Eastern lining both sides of a winding path referred to as the Main Building.

I was glad for her presence. TW kissed her and glided past and up a set of stairs.

Molly ushered me into the parlor. A picture of my parents stared down from a wall like the eyes of Janus. My mother’s dour face and pulled-back-into-a-bun black hair answered the mystery of why I had seen Hazel Lynch as a familiar evil. Mother’s pearls rested against a dress the front of which was a blaze of roses retouched in by some photographer-artist. Daddy’s look was one of brokenheartedness that no amount of retouching could lessen or translate or soften.

Not a hint of blue anywhere in the photograph. Background golds raged the way flames will, the way deciduous trees do in fall. The coloration of the faces served up a belligerence I felt hovered over me, awake or sleeping. A wild in the blood that sooner or later consumes us.

I slept in an upstairs bedroom and so had to be called down to breakfast by a loud rapping at the door of the room. It was TW. He was dressed and telling me what sort of Friday I could expect before my feet touched the floor. His day involved arrangements at the funeral home for the burial on Sunday. He said that today I’d be free to visit with Molly.

Calling hours are tonight and tomorrow night, he said and I nodded from the bed.

Molly has your breakfast downstairs, TW concluded and closed the door.

There was a pitcher and bowl on a washstand by the bed, but I knew it wouldn’t be necessary. TW’s house had indoor plumbing. The bathroom was just down the hall. I had discovered this the night before. It was furnished with a claw-foot tub and running water and a flush toilet. I ran a bath with hot water and slipped into it. In a little while, I pulled the plug and watched water spiral down the drain. Then I got out and dried off and wrapped a robe around me.

I went back to the bedroom and dressed in something from my gray suitcase.

My clothes were wrinkled but felt comforting. Familiar.

I made the bed and went downstairs.

Molly was busy in the kitchen. When she saw me, she stopped what she was doing and motioned for me to sit. The kitchenette was a four-person affair with brushed chrome and padded yellow chairs. It looked modern in a way that seemed appropriate for a house belonging to TW Wolff. In a short while we were together at the table, eating eggs and ham and biscuits.

Light from one of four long windows in the room fell on Molly’s hands. Those bright hands made me connect her movements to the idea that she might help me to see the boy.

I began by asking a question about what had happened to Daddy.

Molly said there had been nothing anyone could do. She began the story of the day they had heard the news: a telephone call from the Junction alerted them to the accident. They were calling the fire that, an accident, and it sounded right since the wind isn’t to be dictated to.

Some people have faces that stay with you, hall portrait or no hall portrait, and Molly’s face was one of those. Soft-featured, mature but not old, intelligent green eyes—like the doctor at Eastern who had leaned over me to describe the shock treatments and what I could expect.

The light wasn’t on Molly’s hands or face now. Not in the same way.

I asked my question: Do you think I could go to Merkie’s and see my boy?

I know what it’s like not to be listened to. This wasn’t that. She was listening.

When she spoke, I knew it wasn’t something she had thought would be asked of her.

Molly rose from the table. She began taking plates and glasses, forks and knives and spoons, to the sink by the long windows. I had no choice but to wait. Waiting was something I had learned to do at Eastern. I rubbed my hand and sat.

Why don’t you dry, Abby—I’ll wash. And we’ll talk about it.

I stopped rubbing my hand and got up from the table and began doing as she asked.

I had to guess where each item belonged in the cupboards, but Molly smiled and nodded, or pointed with a soapsuds-white hand, and we got through the task. Afterwards she made a phone call and talked to someone who seemed to make her repeat every other sentence.

I was standing in the hallway by the portrait of Mommy and Daddy and rubbing my hand, though I was standing. I felt my heart sink as she hung up the phone.

It was clear that she had been talking with TW.

I’m to drive you to see your boy Charlie. Your brother will call Merkie and arrange it. He said you’re not to upset him, Abby—your boy Charlie. He said you’d know what that means.

I thanked her. Not upsetting my son meant I’d continue to be Aunt Abigail.

Charlie had gotten so much bigger I almost didn’t recognize him. Merkie—America, my sister—brought him out onto the porch after she had laid down a warning I didn’t need to hear.

He favored our side of the family, the Wolffs, and was tall for four years old.

Merkie had dressed him in his Sunday clothes. He smelled freshly bathed. His brown hair was damp and I smelled soap as he settled himself into the glider between Molly and me.

Auntie, Mommy says I can’t feed the chickens. Can I feed the chicks, Aunt Abby?

Maybe the world is two things at once: a House of Pain and a House of Pleasure, but I figured it would be the odd woman who could hear a son call another woman Mommy and not feel like she’d been ushered into the House of Pain. I let that injured feeling slip from me.

I asked Charlie a question, ignoring the commandment against his feeding the chickens.

You’re dressed up—would you like to go see The Wizard of Oz with your Aunt Abby?

He perked up. Clearly, even at 4, he knew more about the movie than I did.

I had guessed right: Molly’s presence caused older-sister to check herself before she spoke. America looked to Molly. What do you say about that? she asked.

Molly looked at me. Then at Charlie on the glider. She smiled.

I’ll chaperone, she said.

I shouldn’t have been happy, but I was. Daddy was dead and soon to be buried in the Wolff cemetery overlooking the Pure Oil station and the A & P. I was headed back to that hellhole of a sanitarium in a matter of a few too-short days. But to stand in line with Charlie at the Neon and buy tickets—actually, Molly paid: I hadn’t been trusted with money—and then to go inside and buy popcorn and Dixie cups of Co-cola and sit with my son was answered prayer. A blessing. If I had believed in God, which I didn’t, how could I after Eastern, that God would have been a she and would have looked like Molly and spoken in a voice like my sister-in-law’s.

The movie started. Charlie’s eyes were frozen on the screen. I thought my son was awfully well behaved: not once did he ask for other treats or to go to the bathroom. He seemed terrified by the green-faced witch. He looked down and away then back up for reassurance.

Charlie moved his eyes, following the singing silver can that banged on its chest and intimated that all we need to survive is a heart and friends. A smidgen of kindness. Maybe the luck of the innocent. Certainly a lot more luck than Daddy had the day his ran out.

By the time Dorothy Gale got to see the Wizard the second time, with the charred broomstick of the Witch of the West as proof she had accomplished her mission, Charlie Wolff was hooked. A few more shock treatments and I might forget my whole life, but my hope was that he’d keep this somewhere. It might have been a lot to ask, but I didn’t think so just then.

Copyright © 2015 Roy Bentley. All rights reserved.

Hear “The War of Northern Aggression.”