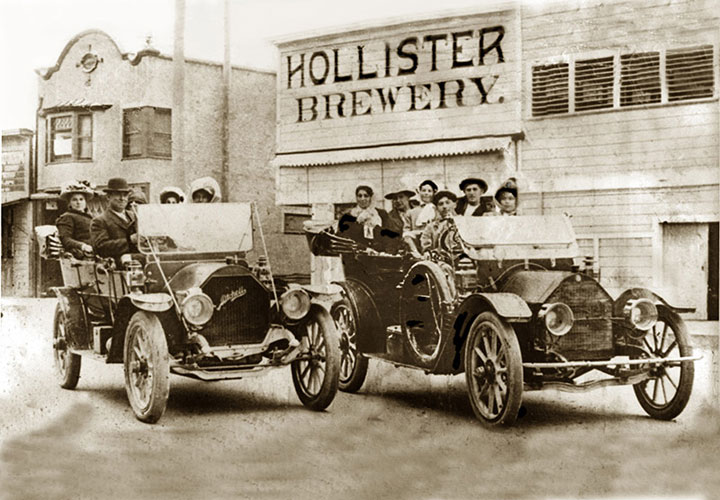

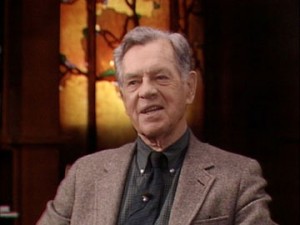

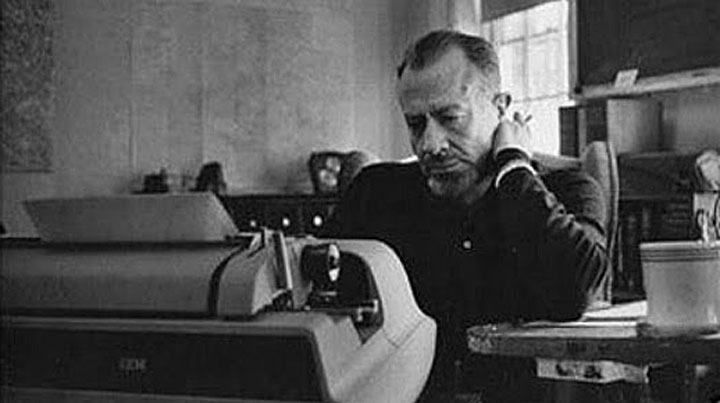

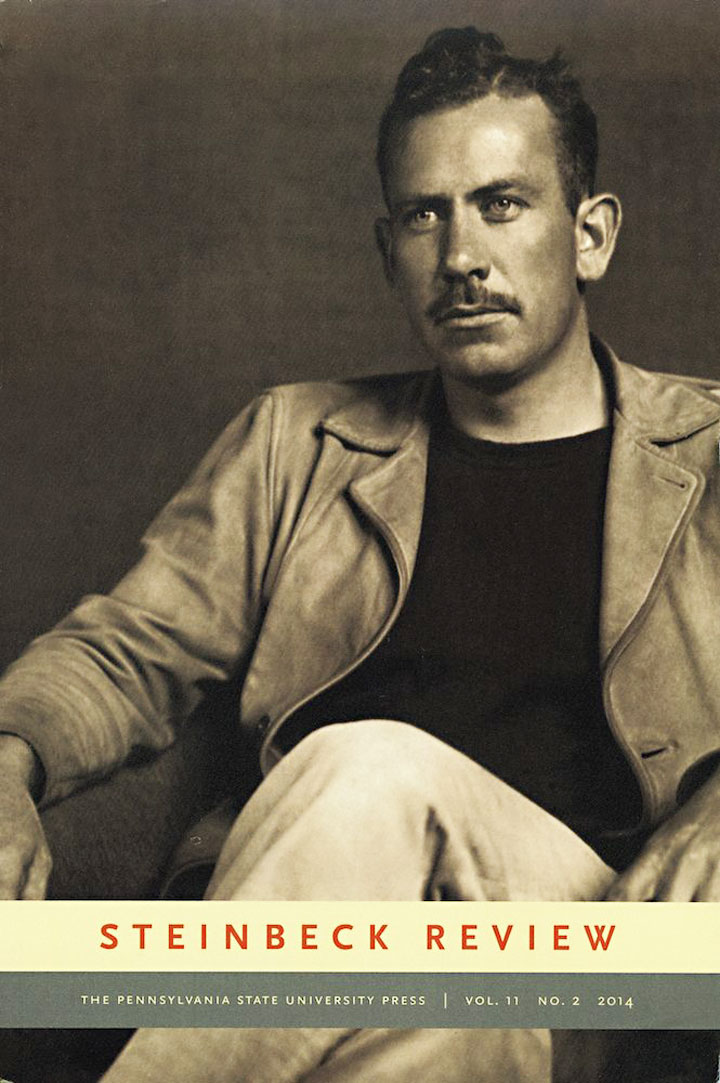

In East of Eden John Steinbeck wrote imaginatively about the Salinas Valley Hamiltons—grandparents, aunts, and uncles on his mother’s Scots-Irish side. But his father Ernst Steinbeck’s people, solid Central California farmer-entrepreneurs living east of Salinas, were also important in the writer’s early life. Folks in Hollister, California, the San Benito County village where the family migrated from New England in the 1870s, like to remind visitors that Steinbeck Country starts in their city, a peaceful farming community set among the rolling hills near historic Mission San Juan Bautista. When John Steinbeck was growing up in Salinas, Hollister was a day’s ride over the steep San Juan Grade, so the Hollister Steinbecks weren’t around as much as the familiar Hamilton clan. But the dramatic story of how they came to Central California is, if anything, even more memorable than that of the Hamiltons, and Steinbeck wrote about it in the 1960s.

Present-day Hollister—the San Benito County, California seat—is a 10-minute drive east off Highway 101 north of Salinas, a must-make side trip whether your primary destination is San Juan Bautista, Monterey, or Salinas, 20 miles to the south on 101. In a curious episode of Steinbeck Country history, the creation of San Benito County was the result of Salinas ambition, and a certain Hollister-Salinas-Monterey rivalry can still be felt when the subject comes up in conversation. The Central California coastal mission settlement of Monterey—California’s first capital—was the original seat of Monterey County, which extended east to include San Benito County when California became a state in 1850. But Salinas Valley farming grew fast following the Civil War and civic boosters in Salinas got ambitious, winning a referendum in 1874 that moved the Monterey County seat to their town. Votes from Hollister and San Juan Bautista—so goes the story—were influenced by the promise to carve out a new San Benito County with a Hollister, California seat.

Present-day Hollister—the San Benito County, California seat—is a 10-minute drive east off Highway 101 north of Salinas, a must-make side trip whether your primary destination is San Juan Bautista, Monterey, or Salinas, 20 miles to the south on 101. In a curious episode of Steinbeck Country history, the creation of San Benito County was the result of Salinas ambition, and a certain Hollister-Salinas-Monterey rivalry can still be felt when the subject comes up in conversation. The Central California coastal mission settlement of Monterey—California’s first capital—was the original seat of Monterey County, which extended east to include San Benito County when California became a state in 1850. But Salinas Valley farming grew fast following the Civil War and civic boosters in Salinas got ambitious, winning a referendum in 1874 that moved the Monterey County seat to their town. Votes from Hollister and San Juan Bautista—so goes the story—were influenced by the promise to carve out a new San Benito County with a Hollister, California seat.

John Adolph and Almira Ann Steinbeck, young John’s Hollister grandparents, grew apricots and operated a dairy, eventually moving into town once their five sons (John Steinbeck’s father Ernst among them) had families of their own. But their roots were in Puritan New England, where Almira’s pious father was known as Deacon Dickson, and Protestant Prussia, where John Adolph and his brother were wood-craftsmen before packing up for Palestine in 1850 with a sister and her husband, a Lutheran missionary. There they met the daughters of Deacon Dickson, a Massachusetts farmer on a mission to the Holy Land, marrying two of the girls in Jerusalem in 1856. Murder, rape, and escape ensued, and the third Dickson sister eventually settled in Hollister, California, too, along with Adolph, Almira, and their five sons. The future novelist was familiar with the family’s story of violence and flight from Palestine to America, and he admired his father’s hardworking people, from whom he inherited hands that liked to garden, fabricate, and repair things. His writing in the 1960s expresses the abiding connection he felt with the prolific San Benito County branch of the Steinbeck family tree.

John Adolph and Almira Ann Steinbeck, young John’s Hollister grandparents, grew apricots and operated a dairy, eventually moving into town once their five sons (John Steinbeck’s father Ernst among them) had families of their own. But their roots were in Puritan New England, where Almira’s pious father was known as Deacon Dickson, and Protestant Prussia, where John Adolph and his brother were wood-craftsmen before packing up for Palestine in 1850 with a sister and her husband, a Lutheran missionary. There they met the daughters of Deacon Dickson, a Massachusetts farmer on a mission to the Holy Land, marrying two of the girls in Jerusalem in 1856. Murder, rape, and escape ensued, and the third Dickson sister eventually settled in Hollister, California, too, along with Adolph, Almira, and their five sons. The future novelist was familiar with the family’s story of violence and flight from Palestine to America, and he admired his father’s hardworking people, from whom he inherited hands that liked to garden, fabricate, and repair things. His writing in the 1960s expresses the abiding connection he felt with the prolific San Benito County branch of the Steinbeck family tree.

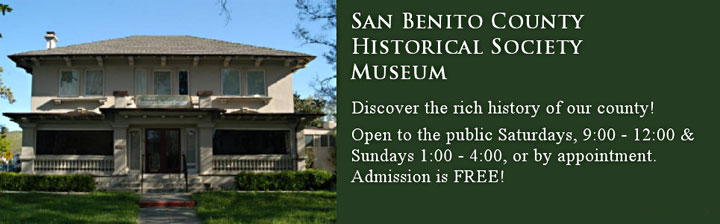

Call the San Benito County Historical Society Museum before your next trip to Central California and see for yourself. The not-for-profit facility is open by appointment only, but the hospitable volunteers who make it run are proud of their heritage and know a lot that isn’t in books about John Steinbeck. Hollister, California is right: “Steinbeck Country starts here!”

Call the San Benito County Historical Society Museum before your next trip to Central California and see for yourself. The not-for-profit facility is open by appointment only, but the hospitable volunteers who make it run are proud of their heritage and know a lot that isn’t in books about John Steinbeck. Hollister, California is right: “Steinbeck Country starts here!”