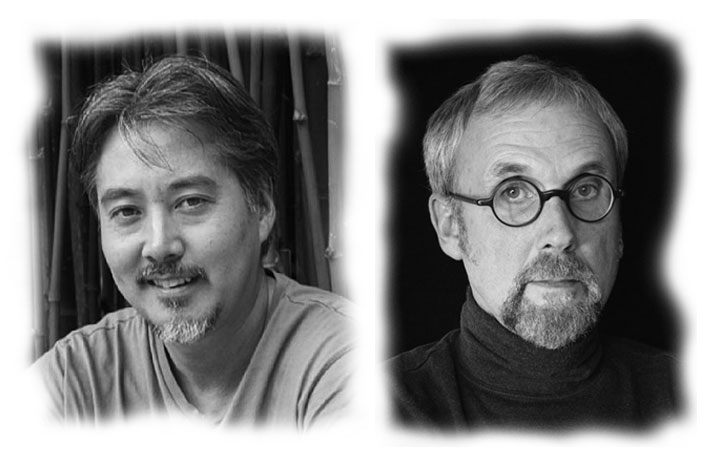

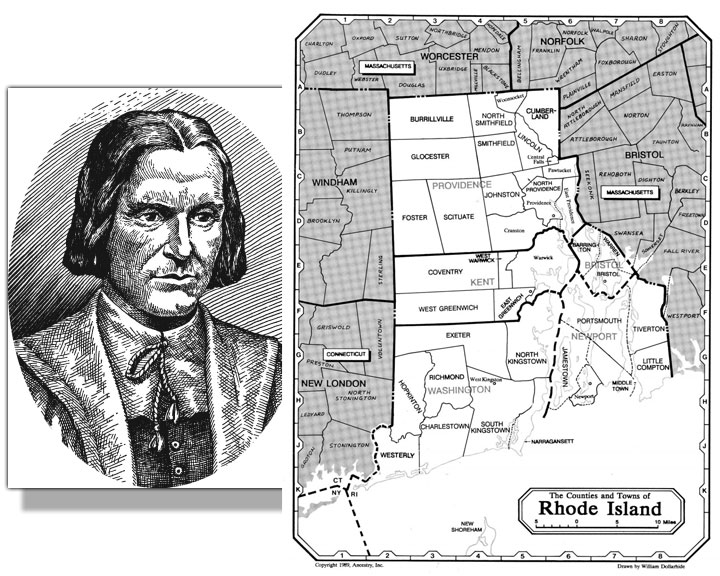

America’s 2014 celebration of The Grapes of Wrath, written in California and published in 1939, became bicoastal on February 1, when Roger Williams University kicked off a two-month exhibition devoted to the novel’s historical context and contemporary relevance with a lecture by Robert DeMott, an international authority on John Steinbeck’s life and work. The location was propitious: Rhode Island, the home of Roger Williams University, began in 1636 as Providence Plantation, a refuge for minorities fleeing religious persecution in neighboring colonies. Rhode Island retains the progressive spirit of Roger Williams, its colonial founder—a spirit that permeates The Grapes of Wrath and the literature of social protest.

America’s 2014 celebration of The Grapes of Wrath, written in California and published in 1939, became bicoastal on February 1, when Roger Williams University kicked off a two-month exhibition devoted to the novel’s historical context and contemporary relevance with a lecture by Robert DeMott, an international authority on John Steinbeck’s life and work. The location was propitious: Rhode Island, the home of Roger Williams University, began in 1636 as Providence Plantation, a refuge for minorities fleeing religious persecution in neighboring colonies. Rhode Island retains the progressive spirit of Roger Williams, its colonial founder—a spirit that permeates The Grapes of Wrath and the literature of social protest.

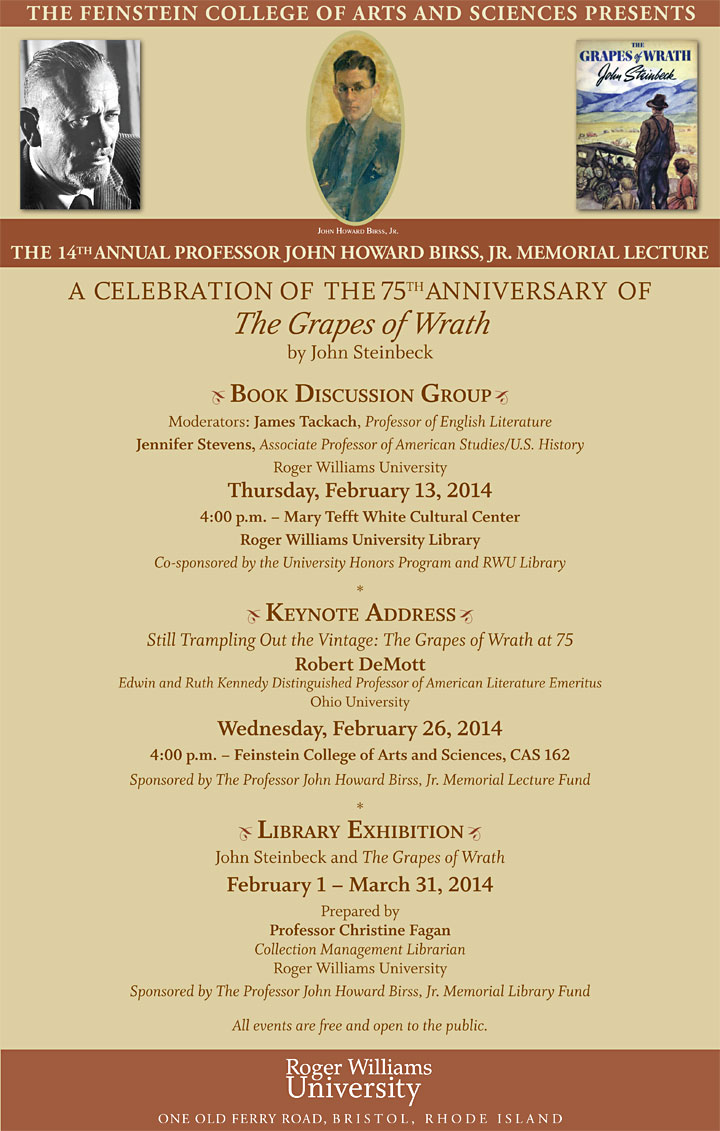

As a collections and exhibitions manager for the Roger Williams University Library, I had the pleasure of collaborating in curating the exhibition with west coast colleagues at San Jose State University and with partners closer to Rhode Island: the Library of Congress; the University of Virginia; Redwood Library in Newport, near the Roger Williams campus; and individuals including Robert DeMott, a distinguished professor emeritus at Ohio University. Rhode Island’s celebration of The Grapes of Wrath is part of Roger Williams University’s Professor John Howard Birss, Jr. Memorial Program, an annual series of events honoring great works of literature now in its 14th year.

As a collections and exhibitions manager for the Roger Williams University Library, I had the pleasure of collaborating in curating the exhibition with west coast colleagues at San Jose State University and with partners closer to Rhode Island: the Library of Congress; the University of Virginia; Redwood Library in Newport, near the Roger Williams campus; and individuals including Robert DeMott, a distinguished professor emeritus at Ohio University. Rhode Island’s celebration of The Grapes of Wrath is part of Roger Williams University’s Professor John Howard Birss, Jr. Memorial Program, an annual series of events honoring great works of literature now in its 14th year.

The Grapes of Wrath in Image, Text, and Facsimile

The exhibition—open to the public through March 31—is designed around themes such as the Dust Bowl and migrant workers and employs historical and contemporary photographs to document the background of the writing, publication, and aftermath of The Grapes of Wrath. The Dust Bowl section is composed primarily of Farm Security Administration photographs from the period. The section on California migrant workers today includes photographs from The Migrant Project: Contemporary California Farm Workers by Rick Nahmias. The book focus of the exhibition features facsimile selections from the digitized manuscript of The Grapes of Wrath, written in Steinbeck’s cramped, hard-to-read hand at his home in the Santa Cruz mountains, far from Rhode Island but close to his novel’s California context.

Why Rhode Island Loves Carol Henning Steinbeck

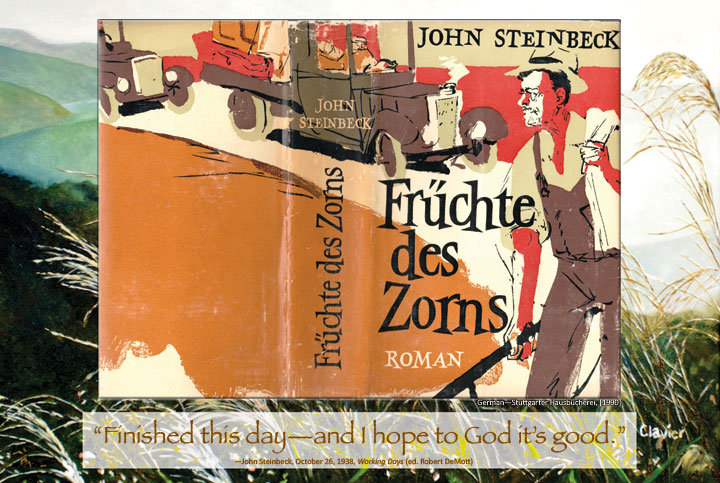

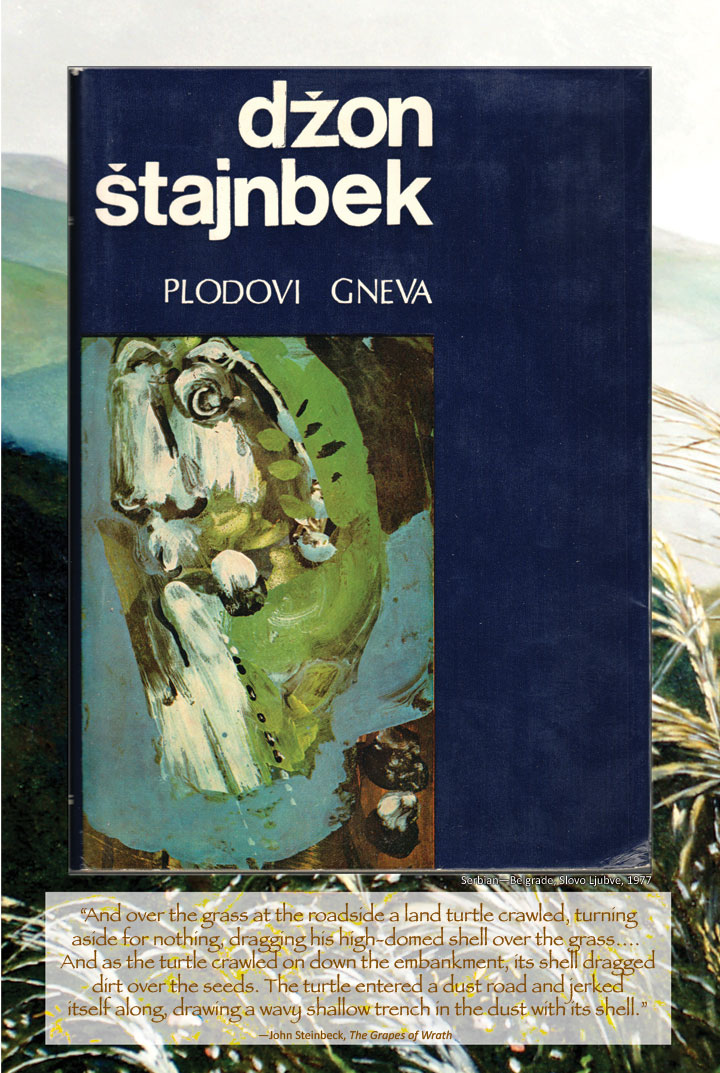

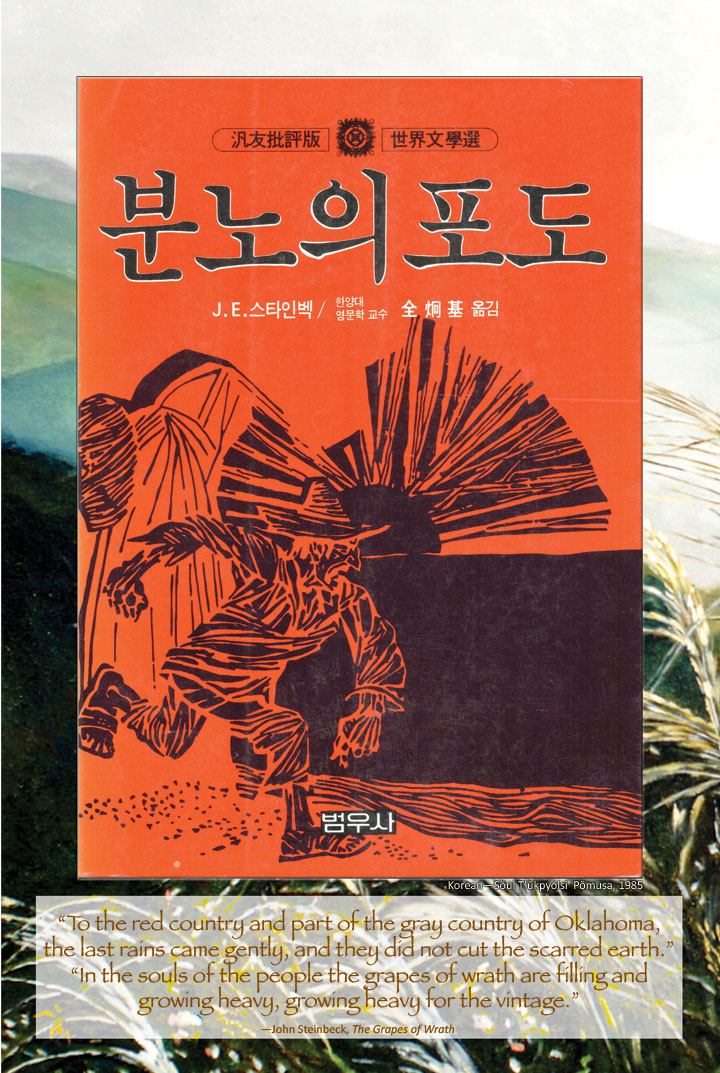

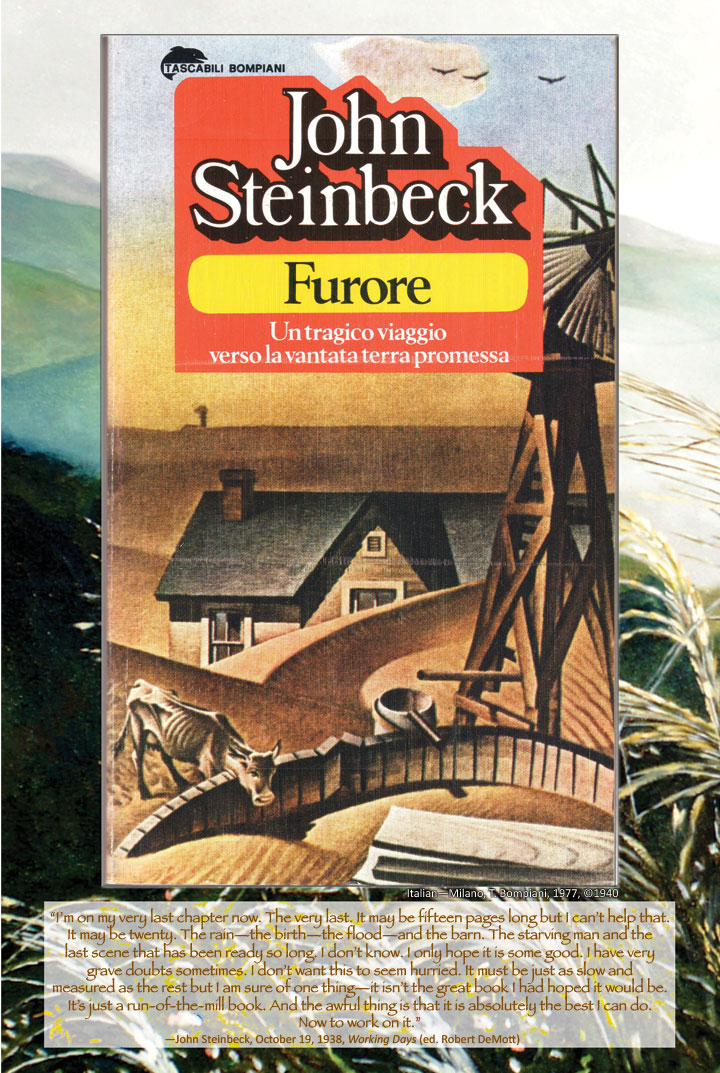

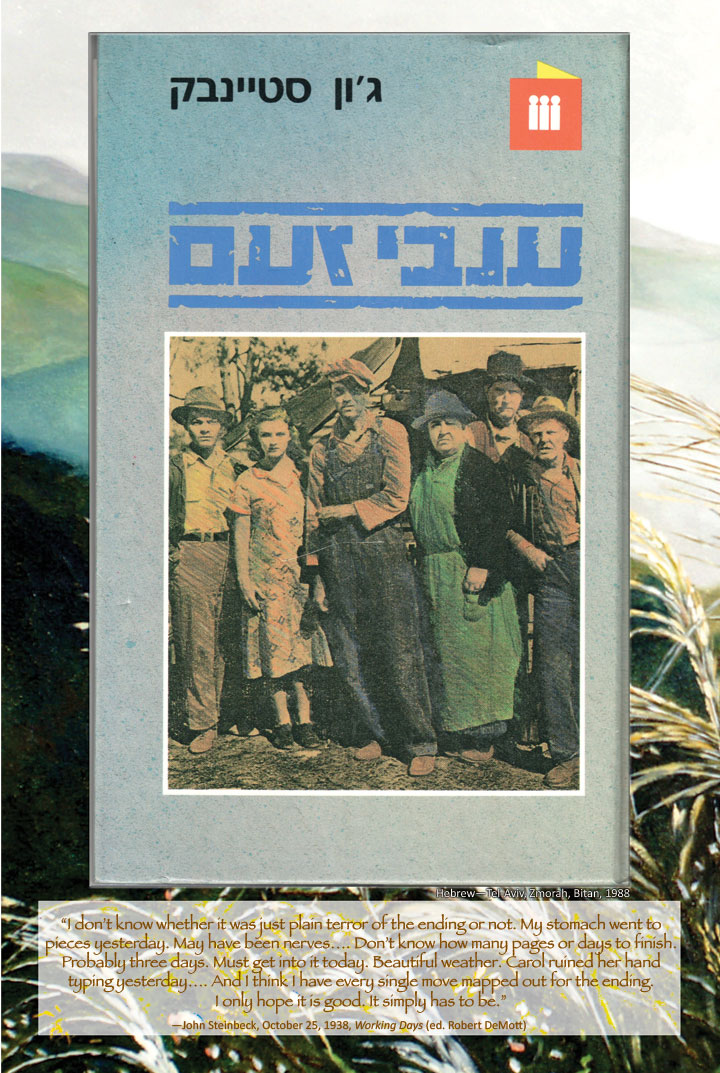

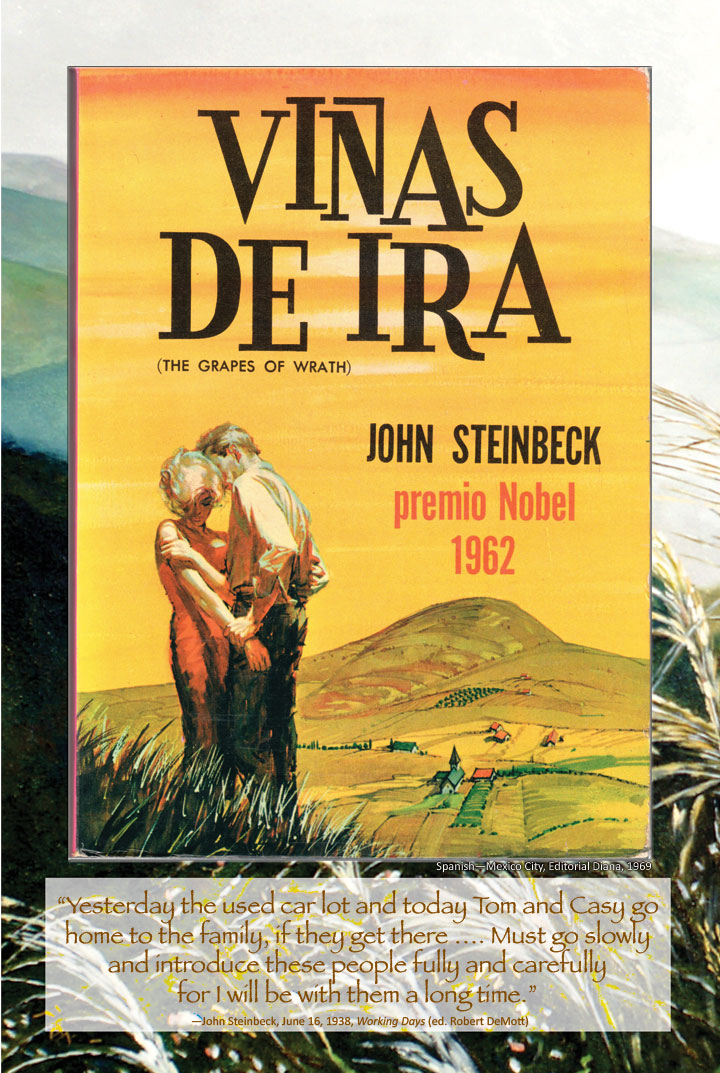

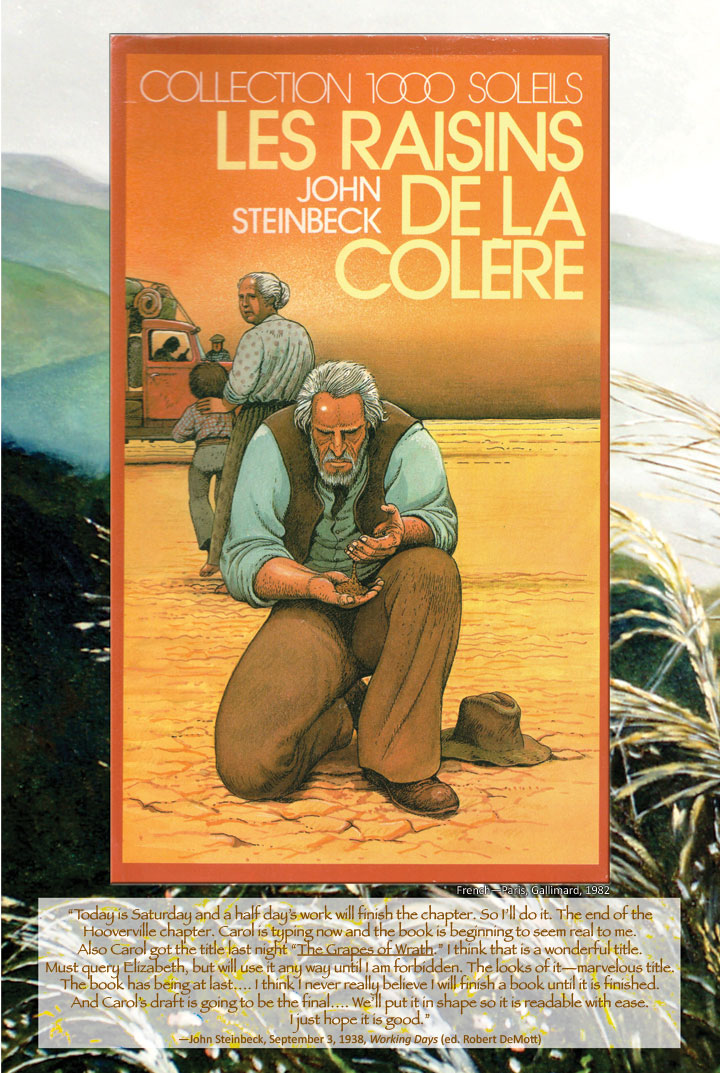

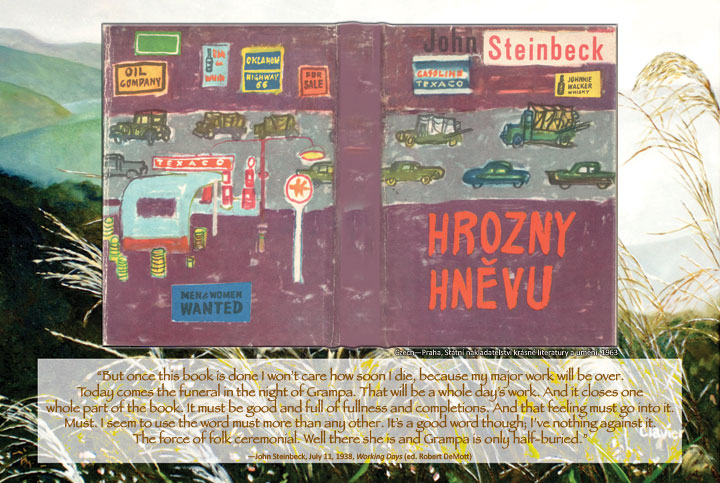

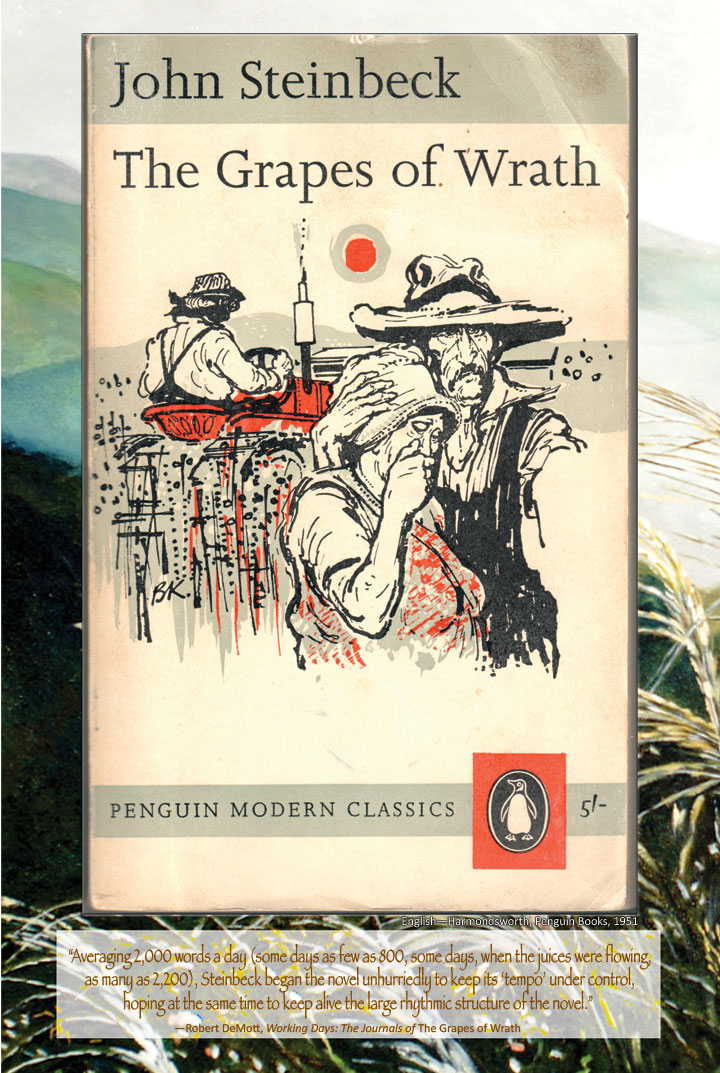

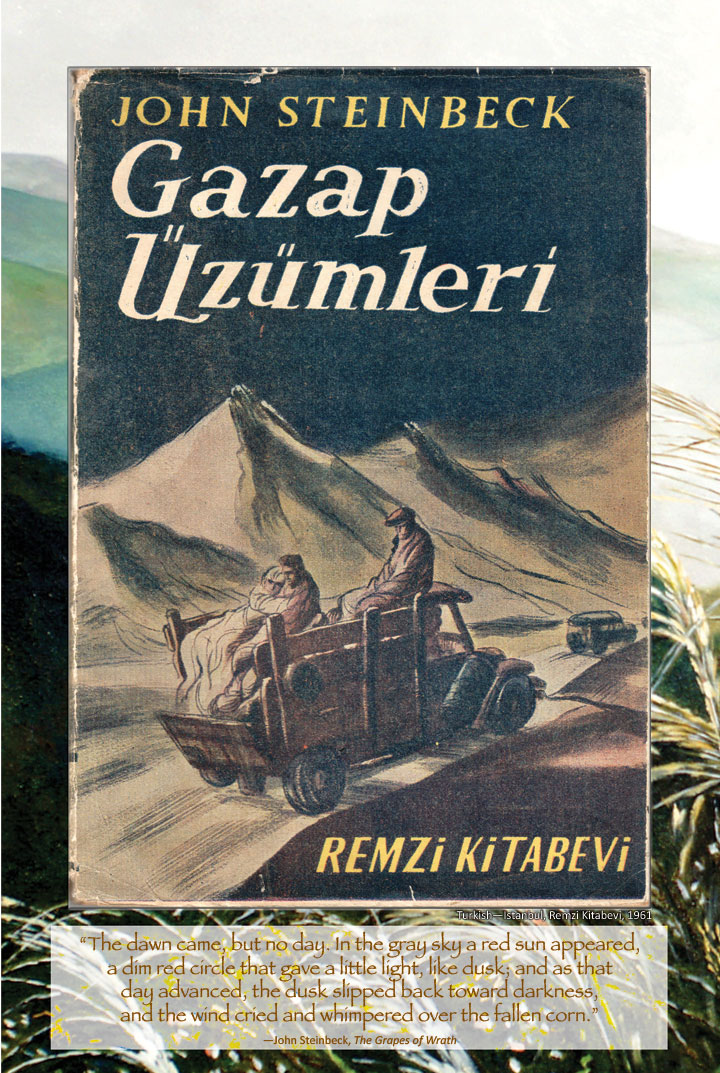

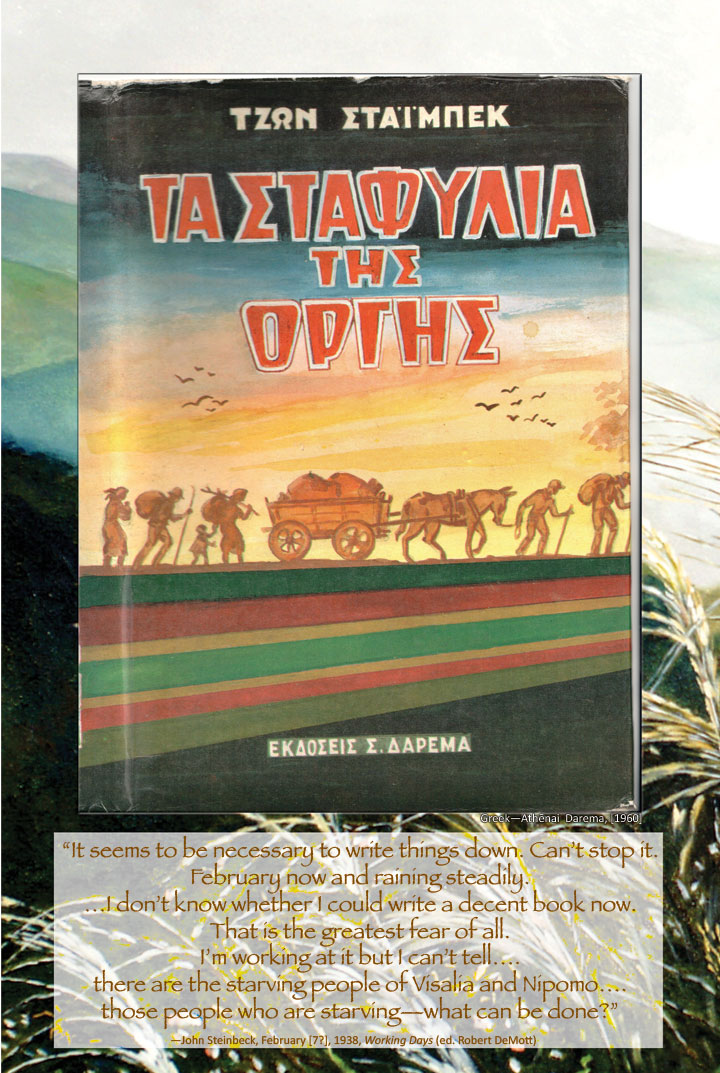

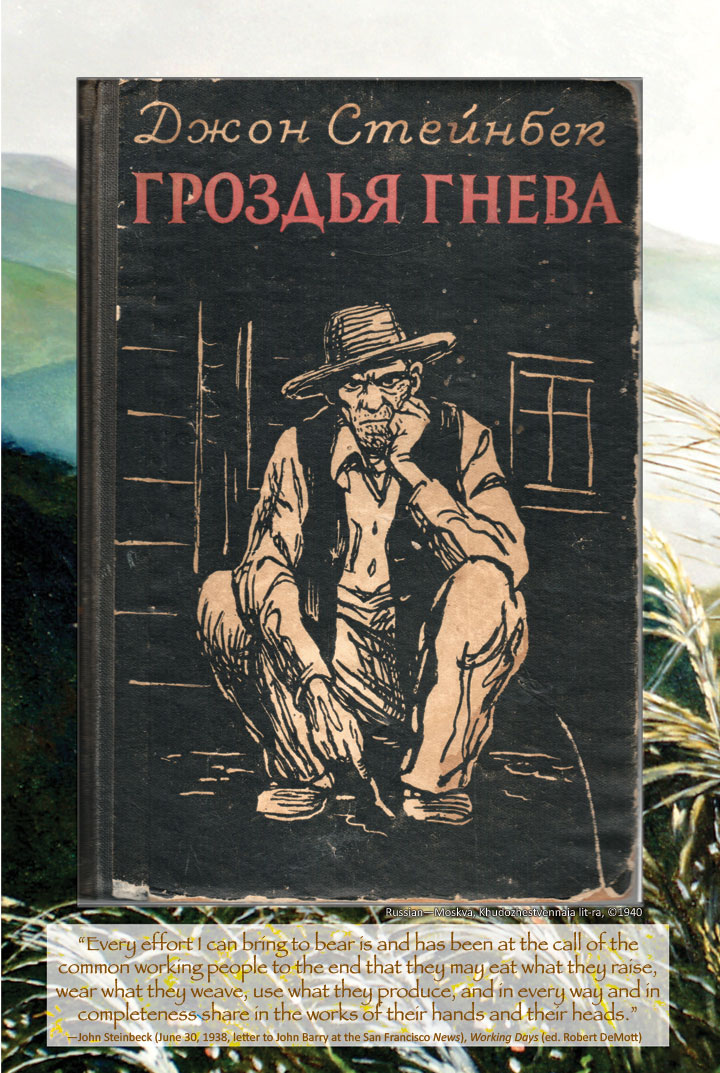

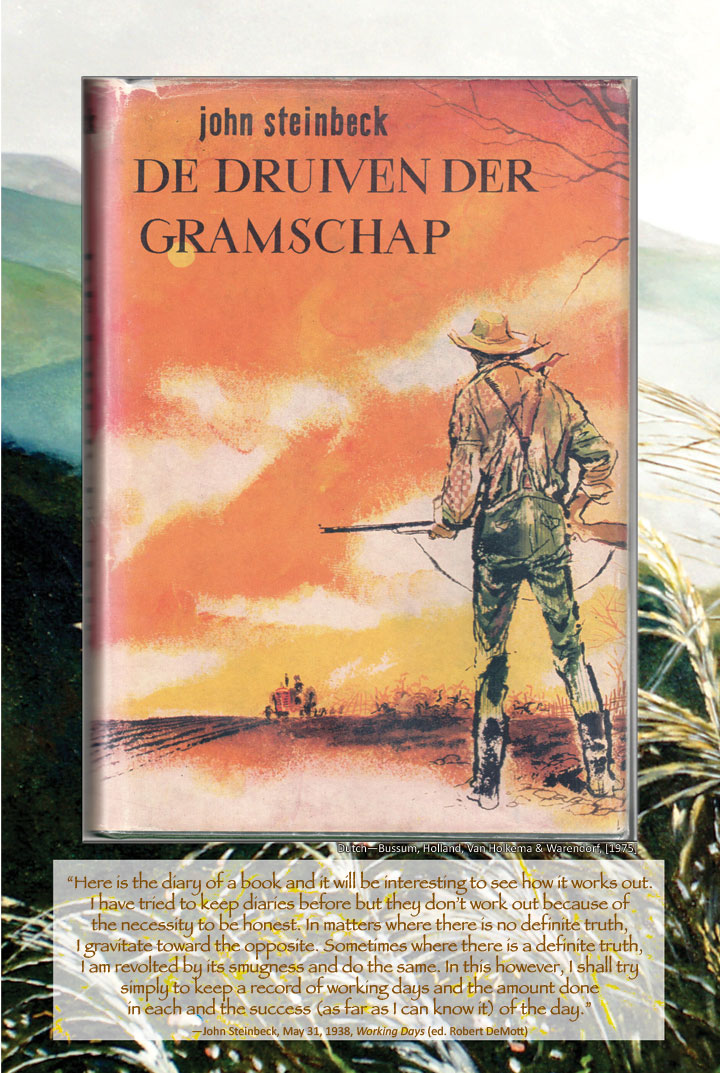

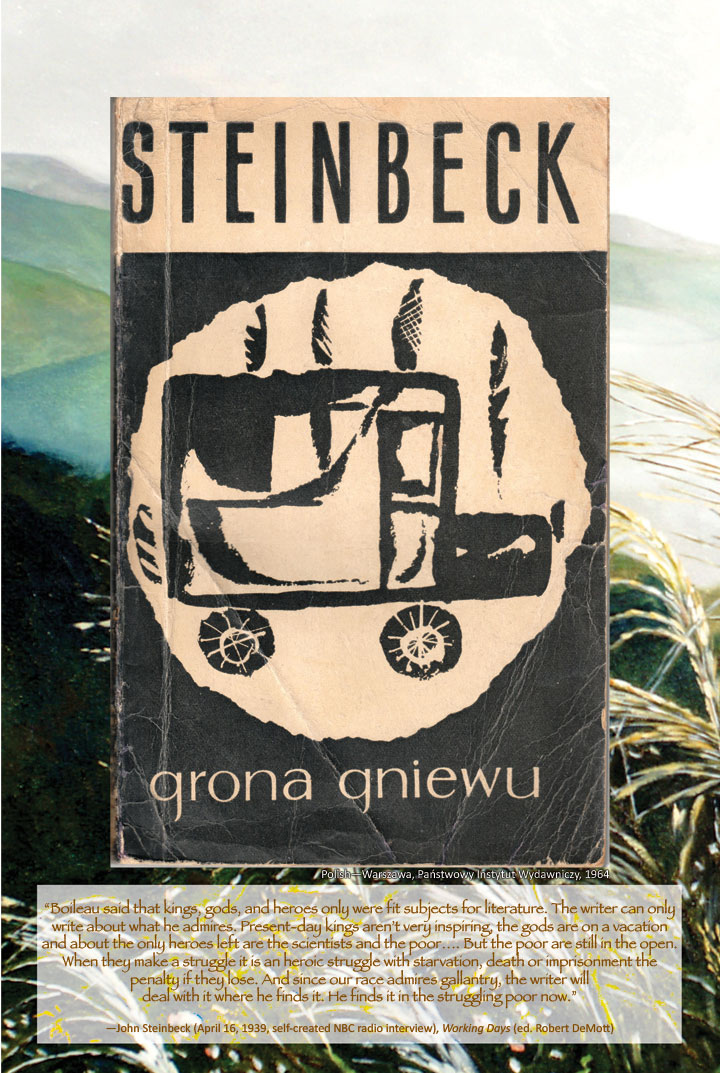

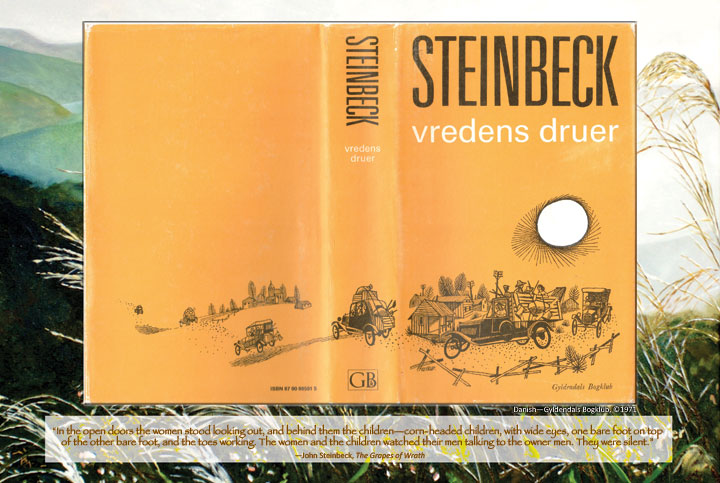

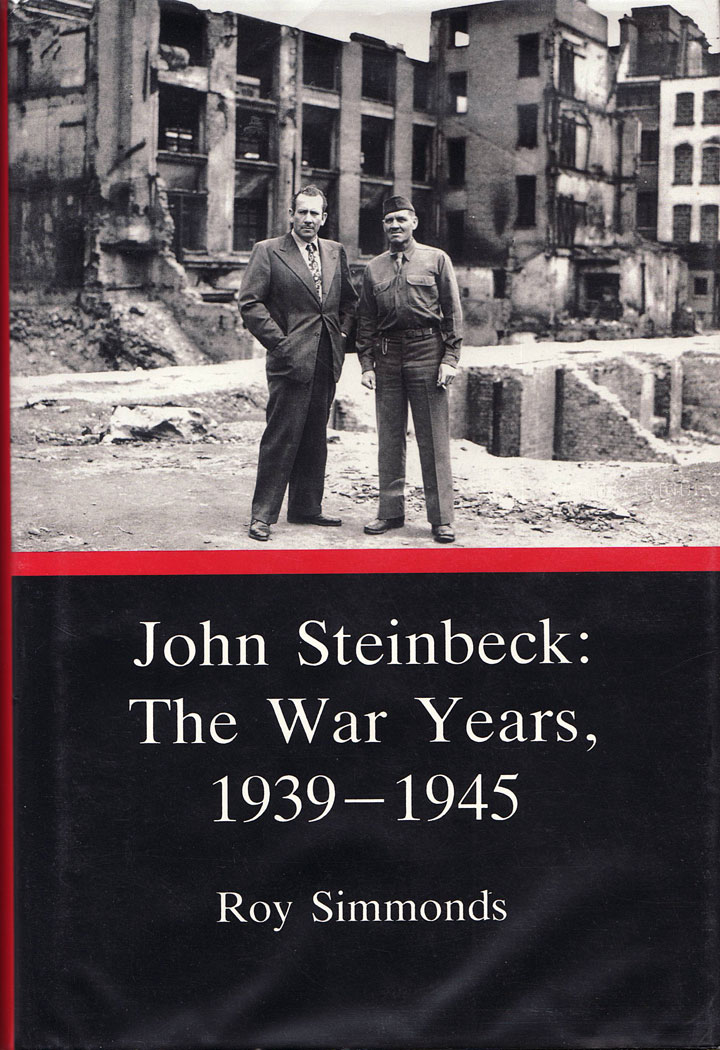

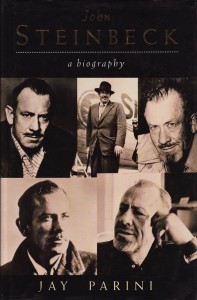

Carol Henning, Steinbeck’s first wife, was an artist and activist who served as the author’s amanuensis and adviser. The title of The Grapes of Wrath was her idea, and she was an intuitive editor. At Roger Williams University, we chose to honor her talent and independence with samples of her drawings and sculpture. Along with Susan Shillinglaw’s recent biography of the Steinbeck-Henning marriage, the book section includes Working Days, Robert DeMott’s meticulous edition of the journal entries made by Steinbeck during and following the writing of The Grapes of Wrath. Like our colleagues at the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies in San Jose, California, we chose cover art from foreign-language editions of The Grapes of Wrath that illustrate specific passages from Working Days.

Roger Williams Welcomes You in Person or Online

Rhode Island is small, friendly, and accessible. Visit us as we celebrate The Grapes of Wrath in the state with the motto Hope founded by Roger Williams—like Steinbeck, an advocate of liberty and apostle of hope who changed the course of history. If you can’t come to the Roger Williams University campus, share the experience online. Our exhibition page features a section not included in the physical exhibition: the adoption of the Library Bill of Rights by the American Library Association. A direct result of the censorship issues associated with The Grapes of Wrath, this pioneering document is powerful proof that The Grapes of Wrath matters, the point and purpose of liberty-loving Rhode Island’s bicoastal collaboration.