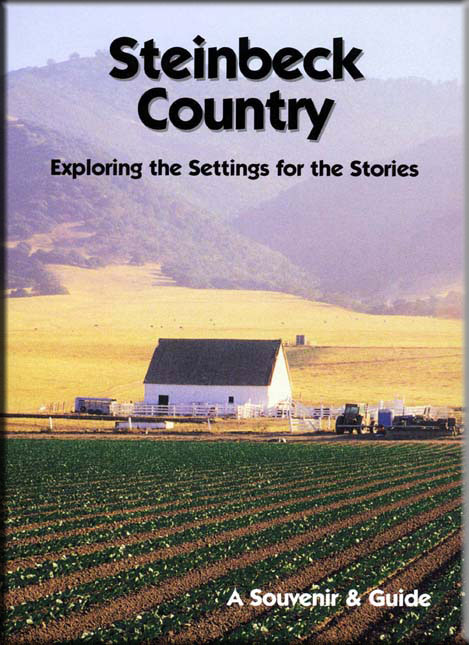

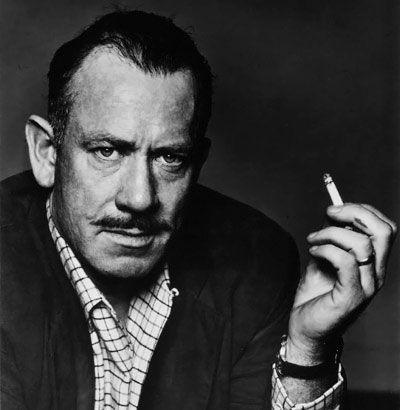

The Steinbeck Country & Beyond app—published by Windy Hill Publications in collaboration with the National Steinbeck Center—has been updated to include new photographs and additional entries about Route 66, the road followed by the Joad family in The Grapes of Wrath.

The Steinbeck Country & Beyond app—published by Windy Hill Publications in collaboration with the National Steinbeck Center—has been updated to include new photographs and additional entries about Route 66, the road followed by the Joad family in The Grapes of Wrath.

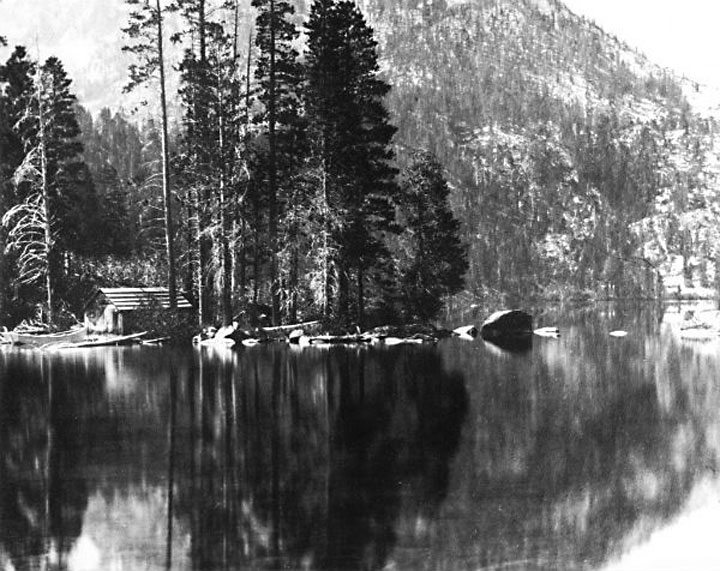

But the most unusual image added to the app is an historic view of the caretaker’s cabin at Cascade Lake near Lake Tahoe, where Steinbeck completed work on his first novel, Cup of Gold, a decade prior to The Grapes of Wrath. Although the cabin was removed some years ago, the current owners of the property provided the historic black-and-white photograph. Permission to reproduce it in the app was granted by the rights owner, photographer James Hill of Tahoe City, California.

Timed to coincide with the National Steinbeck Center’s upcoming Route 66 road trip along the “mother road and the road of flight” taken by Depression Era migrants to California’s Promised Land, three new entries cover communities along Route 66 described in The Grapes of Wrath. Part I covers Oklahoma; Part II covers Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona; and Part III lists California locations mentioned in The Grapes of Wrath.

A free version of the app describing approximately 200 sites worldwide associated with John Steinbeck’s life and work is distributed by Sutro Media through the iTunes App Store. It is also available for Android systems from Google play. For more information visit the app’s website.