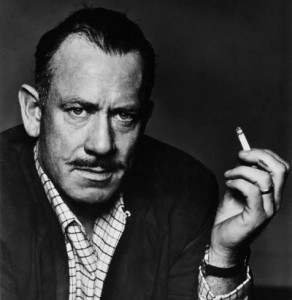

Sinclair Lewis, a Nobel Prize-winning fiction writer admired by John Steinbeck for his dissection of contemporary American life, envisioned a future fascistic America in a novel published the same year J. Edgar Hoover became director of the FBI. Released in 1935, It Can’t Happen Here is a more realistic if less convincing depiction of dictatorial government than George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, published in 1949. Books from John Steinbeck about totalitarianism during this turbulent period consist of a slender play-novelette, The Moon Is Down—and it involves enemy invasion, not domestic dictatorship. But based on FBI files and recent events, I believe government surveillance on an Orwellian scale would attract Steinbeck as a subject if he were writing today. His story might start with Hoover.

Sinclair Lewis, a Nobel Prize-winning fiction writer admired by John Steinbeck for his dissection of contemporary American life, envisioned a future fascistic America in a novel published the same year J. Edgar Hoover became director of the FBI. Released in 1935, It Can’t Happen Here is a more realistic if less convincing depiction of dictatorial government than George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, published in 1949. Books from John Steinbeck about totalitarianism during this turbulent period consist of a slender play-novelette, The Moon Is Down—and it involves enemy invasion, not domestic dictatorship. But based on FBI files and recent events, I believe government surveillance on an Orwellian scale would attract Steinbeck as a subject if he were writing today. His story might start with Hoover.

Fiction Writer Question: What Would Steinbeck Say?

Also created in 1935, Hoover’s FBI left a blueprint for the kind of American police state imagined by Lewis in It Can’t Happen Here. By blending secrecy, efficiency, and independence from oversight, Hoover built a hidden system of government surveillance years before digital data mining and other tools of the NSA. Hoover’s first speech to the International Association of Chiefs of Police, delivered in 1925, reads like the mission statement for a future NSA security state: “The mighty, irresistible current of world-wide, cosmic forces, have created the necessity and impetus for the inception and growth of an organization which will serve to centralize and crystallize the efforts of those who would meet the exigencies of our changing times by a pooling of all of the wisdom and power of the guardians of civilization, the protectors of Society.”

The differences between Steinbeck and Hoover—in personality, politics, and lifestyle—have already been covered. Richard Powers’ biography, The Life of J. Edgar Hoover: Secrecy and Power, documents Hoover’s deep attachment to moralistic beliefs and dictatorial behavior. Top Secret: The FBI Files on John Steinbeck, edited by Thomas Fensch, demonstrates how easily personal conflicts became public crusades in Hoover’s FBI. If Hoover were still in charge today, Edward Snowden would be caught between deadly opposing forces with identifiably authoritarian faces. Putin or Hoover? Which would be worse for a fugitive like Snowden? Only Richard Nixon rivaled Hoover at creating fear in diissenters, and by 1974 both men had left the stage. Of their odious personality type, only Putin and North Korea’s little caesar remain as players on the international stage.

The mighty, irresistible current of world-wide, cosmic forces, have created the necessity and impetus for the inception and growth of an organization which will serve to centralize and crystallize the efforts of those who would meet the exigencies of our changing times by a pooling of all of the wisdom and power of the guardians of civilization, the protectors of Society.

As noted in Top Secret: The FBI Files on John Steinbeck, America’s foremost fiction writer blew the whistle on Hoover in a private letter to Roosevelt’s attorney general. The immediate consequences to Steinbeck were personal, but they passed. Edward Snowden exposed the NSA’s Orwellian overreach in public, on a global scale, and his consequences are ongoing. Congress is making noise, President Obama says he’ll investigate, and mainstream journalists in America persist in challenging Snowden’s character. To readers of the FBI files on John Steinbeck this all sounds too familiar. It wouldn’t surprise the fiction writer. His experience was similar.

Steinbeck would certainly fear for Snowden’s safety going forward. While he liked Russians, America’s foremost fiction writer hated Stalinism and disliked authoritarians, at home or abroad. He was passionate about democracy but thought the cold war was a political power game threatening human survival. He supported his government in periods of real war but opposed its excesses in times of uneasy peace. Like William Faulkner—another American fiction writer who exalted individual freedom—he gave a Nobel acceptance speech that’s as relevant today as it was it was it was delivered .

For the Answer, Check the FBI Files on the Author

Steinbeck’s speech in 1962 presents an individualist’s answer to authoritarians like Hoover. Steinbeck’s words in his acceptance speech constitute a plausible opening for the anti-totalitarian novel he never wrote: “Fearful and unprepared, we have assumed lordship over the life and death of the whole world of all living things. The danger and the glory and the choice rest finally in man. The test of his perfectibility is at hand.”

In the half-century since Steinbeck delivered his speech, technology and terrorism have intervened in ways that would have horrified the fiction writer. Today the consequences of poking Big Brother in the eye are more serious—and the dimensions of surveillance greater—than he could ever imagine. It required a fiction writer with George Orwell’s direct experience in colonial law enforcement to envision a system of state surveillance anything like today’s NSA. Orwell was supervising an extensive system of domestic surveillance in the British colony of Burma in 1924, the year Hoover became acting director of investigation for the U.S. Department of Justice.

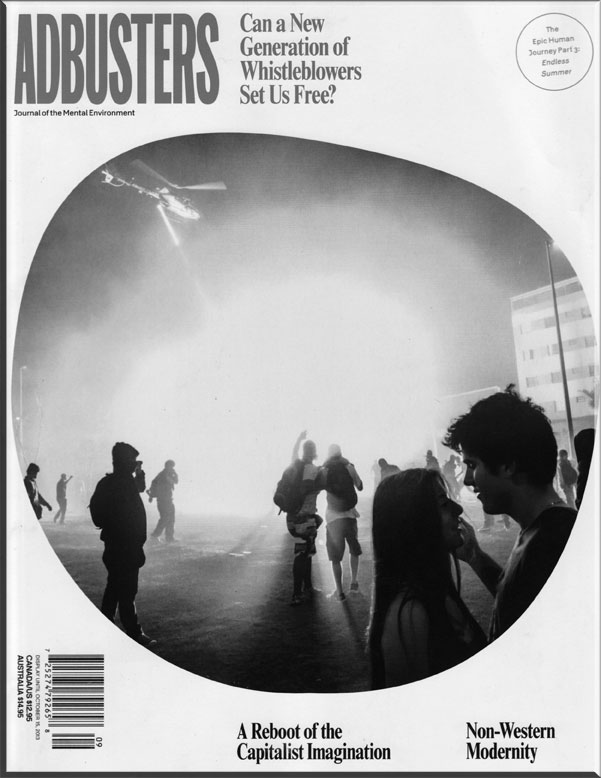

An article in a recent issue of Adbusters magazine speculates that the Orwellian NSA data mining program disclosed by Edward Snowden is only the tip of an iceberg—one that threatens to sink democracy as definitively as the ghastly surveillance system imagined in Nineteen Eighty-Four. Employing the same pastoral image used by Orwell and Steinbeck to portray evil despoiling innocence in fiction, the magazine warns Americans to wake up before escapist slumber becomes actual, existential hell: “America has truly become a nation of sheep . . . . Trust the shepherd. He’ll lead us to pasture.” Overstatement? Only if you think nightmares never come true. If that’s a challenge, try this for size:

Joseph Stalin, the Soviet dictator denounced by John Steinbeck, was an ex-church seminarian who murdered millions of his people. Vladimir Putin, Snowden’s ominous host, formerly ran the KGB, the bloody successor to Stalin’s secret police. Steinbeck’s political hero Roosevelt cooperated with Stalin during World War II. Barack Obama, Snowden’s chief critic and a progressive like Roosevelt, visibly dislikes Putin—but plans to attend Russia’s G-20 conference anyway. Where all this is going is anybody’s guess. John Steinbeck became a hero for exposing economic inequality and injustice in his day. Edward Snowden may become a martyr for revealing massive surveillance in ours. However uncertain the outcome, the connections are clear. Steinbeck’s story suggests history will take Snowden’s side.

William Ray, the editor of five books and former editorial director at New Wedding Planet, is the author of articles on John Steinbeck and the founder of SteinbeckNow.com.