A trove of documents donated to Stanford University—the S.J. Neighbors collection of John Steinbeck papers, 1859-1999—adds dramatic detail to a literary life story that started in 19th century Germany and Palestine and became synonymous with 20th century California and America. Totaling 256 items, the acquisition is the largest since 1999, when Wells Fargo funded the addition of a major collection of Steinbeck material to the holdings of the newly renovated Green Library, which first opened in 1919, the year Steinbeck enrolled at Stanford as a freshman. The new collection includes correspondence to and from John Steinbeck, notebooks kept by his American grandmother, Almira Steinbeck, and lecture notes written by her earnest, German-born husband about their missionary work in Palestine and the attack on their compound in Jaffa that sent them packing for the United States, just in time for the outbreak of the Civil War. According to Rebecca Wingfield, curator of British and American literature, the addition of the S.J. Neighbors collection makes the Stanford University Library the most important resource anywhere for research on Steinbeck’s roots. Her colleague Ben Stone, curator of American and British history, notes that the school’s commitment to Steinbeck includes access to the collection by regular readers of the restless American writer who never got around to telling his grandparents’ back story and disappointed his family by leaving Stanford without a degree.

Exhibit, Conference Show Steinbeck is in Good Hands

The local link between Ludwig van Beethoven and John Steinbeck, a man who loved Broadway but preferred Bach, gave minds at San Jose State University—where the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies shares space with the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies—the bright idea for The Art of Biography, an exhibit of images and objects from the two collections that runs through July 6, 2019 on the fifth floor of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Library. Timed to coincide with the 2019 Steinbeck conference, held May 1-3, the exhibit’s Steinbeck content was created by Alexandra Mezza and Allison Galbreath, graduating students in the MFA creative writing program directed by Nick Taylor, who also serves as director of the Steinbeck center.

The local link between Ludwig van Beethoven and John Steinbeck gave San Jose State University the idea for an exhibit of images and objects from the two collections.

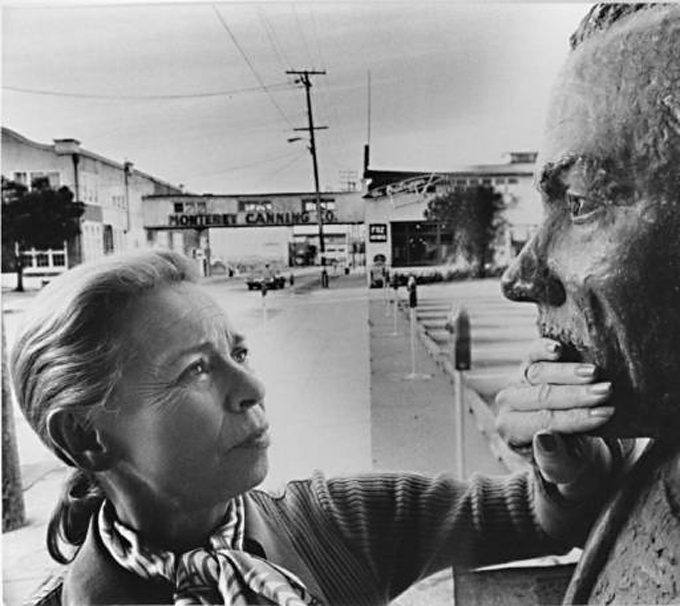

Like this exhibit photo of Elaine Steinbeck, taken at Cannery Row in 1975, the 2019 conference field was dominated by women with a special touch for John Steinbeck. Speakers included Mary Papazian, the Milton scholar who became San Jose State University’s president since the last Steinbeck conference was held three years ago; Noelle Brada-Williams, the new chair of the university’s English department; Susan Shillinglaw, English professor and author of the artful biography, Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage; Marisa Plumb, also of the English department; Barbara A. Heavilin, professor emeritus at Taylor University and editor-in-chief of Steinbeck Review; Mimi Gladstein, the University of Texas, El Paso, superstar who writes about Steinbeck, Hemingway, and Faulkner’s women; Cecilia Donohue, a retired professor of English at Madonna University; Elisabeth Bayley, who teaches at Loyola University in Chicago; Aya Kubota, a professor at Japan’s Bunka Gakuen University; Lori Newcomb, a teacher at Wayne State College; Naama Cohen of Tel Aviv University; Danica Cerce, a member of the faculty of the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia; Debra Cumberland, a teacher at Winona State University; Robin Provey, a graduate student at Western Connecticut State University; Jennifer Ren, an entering law student at the University of Houston; and Audry Lynch, the veteran educator from Boston who had the unusual experience of interviewing each of Steinbeck’s three wives in California.

Like the exhibit photo of Elaine Steinbeck taken in 1975, the 2019 conference field was dominated by women with a special touch for John Steinbeck.

Women also filled the stage for after-hour attractions during the conference. Three 2018-19 Steinbeck Fellows in Creative Writing at San Jose State University—Katie M. Flynn, Kirin Khan, and Christine Vines—read from their fiction on opening night. When the formal program closed on Friday, 20 of 50 conference attendees boarded the bus for Salinas, where Susan Shillinglaw led a look-and-listen tour that included the Red Pony Ranch, the Steinbeck House, and the National Steinbeck Center, where Michele Speich—a nonprofit professional from Monterey—recently succeeded Shillinglaw as the Salinas organization’s executive director. Steinbeck House dinner was served by members of the Valley Guild, the group of mostly female volunteers who bought the home in the 1970s and pay the bills by running the restaurant and encouraging donations. If Martha Heasley Cox had such women in mind for the future of John Steinbeck’s legacy when she started the center that bears her name, also in the 1970s, today’s results would have to make her happy.

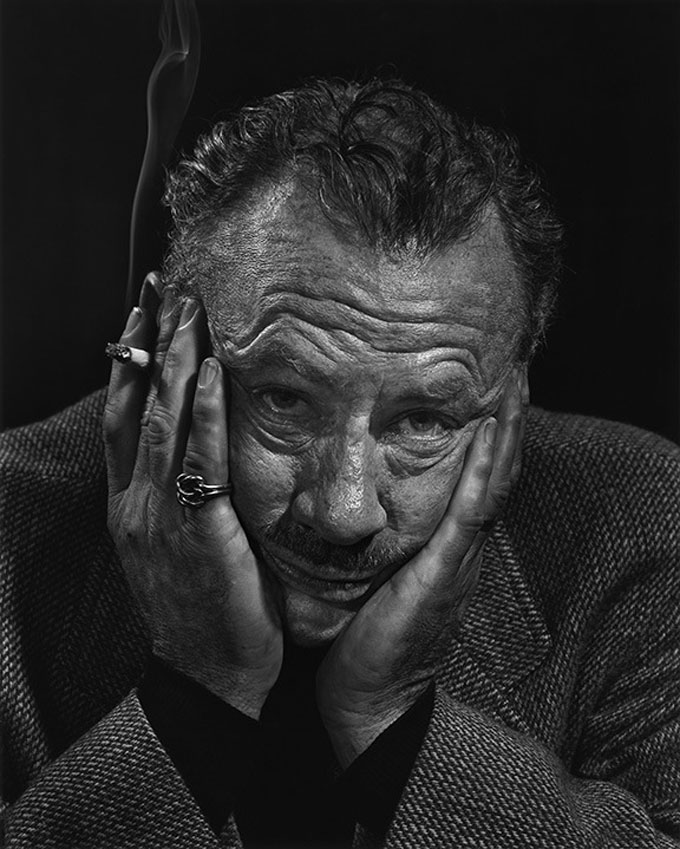

Photograph by John Bryson courtesy of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies.

Profile by Martin Chilton Best Writing on Steinbeck in 2018

A December 20, 2018 piece published by The Independent to mark the 50th anniversary of John Steinbeck’s death could be the best writing about Steinbeck in a milestone year for journalism devoted to an author who still makes waves. The compelling profile of Steinbeck by Martin Chilton, culture editor of England’s Telegraph chain, describes “a flawed genius” who was chronically ill, frequently angry, but never inconsequential. “When I met the singer and actor Harry Belafonte,” recalls Chilton, who also writes about sports and music, “he told me Steinbeck ‘was one of the people who turned my life around as a young man,’ inspiring ‘a lifelong love of literature.’” Chilton’s take on Steinbeck’s life turns on milestone events—brushes with death, bouts of depression, divorces and disappointments—whose cumulative weight made Steinbeck “Mad at the World,” the title of the biography by William Souder scheduled for publication by W.W. Norton in 2019. A quotation from our 2015 interview with Souder includes a hyperlink to Steinbeck Now, making 2018 a milestone year for us too.

Photo of Martin Chilton courtesy of the Telegraph newspaper group

Sag Harbor Library Returns John Steinbeck’s Love

When John Steinbeck and his wife Elaine bought a home in Sag Harbor, New York in 1955, the whaling village on the eastern tip of Long Island had the essential ingredients for happiness the controversial writer missed after leaving Pacific Grove, California—water, history, and a casual lifestyle, like Cannery Row, that allowed for anonymity. New England whaling had gone the way of the California sardine industry long before the couple’s arrival, but weekend fishing was still good and a Sag Harbor tradition of hospitality to authors, starting with James Fenimore Cooper, survived. That particular tradition is on display again through December 20, 2018, the 50th anniversary of John Steinbeck’s death, with a commemoration of Steinbeck’s life by Sag Harbor’s John Jermain public library, named after a local hero from Cooper’s time. Activities include films, library talks, and a digital wall of remembrance for residents who knew or saw Steinbeck when he and Elaine were in town. (Catherine Creedon, the library director, is shown with Preservation Long Island award recipient Zach Studenroth in this April 11, 2018 photograph by Michael Heller, courtesy of the Sag Harbor Express.)

Parallels Meet: Steinbeck, Moberg, and Two Migrations

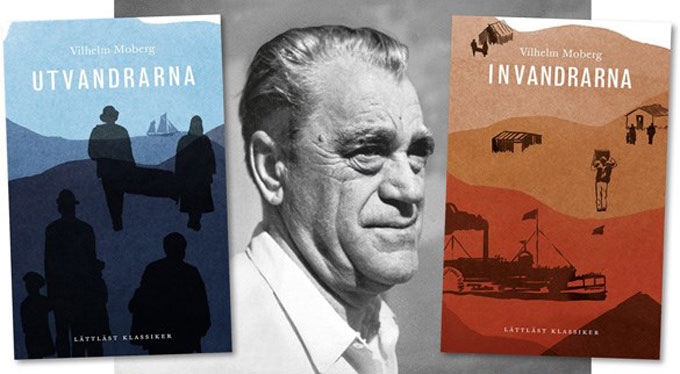

Steve Hauk, the author of Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, contributed to this account of an overlooked aspect of John Steinbeck’s life, writing, and reputation as a 20th century American internationalist: his association with the Swedish writer Vilhelm Moberg, with whom he shared political sympathies, geographical proximity, and personal traits, including depression.—Ed.

John Steinbeck and Vilhelm Moberg had more in common than literary greatness. Sensitive to the humble, powerless, and downtrodden, both writers documented social injustice with abiding sympathy and convincing clarity in works of fiction that became classics. Both wrote novelistic sagas of human migration that became major movies—Steinbeck’s 1930s protest novel The Grapes of Wrath and The Emigrants, the series of four novels in Swedish written by Moberg and made into a pair of feature films starring Liv Ullmann and Max von Sydow in the 1970s. Both men did some of their best writing on California’s Monterey Peninsula, though at different times, and may have met there in the late 1940s. “In one of his letters home, Moberg mentions having met Steinbeck,” notes Swedish scholar Jens Liljestrand, who speculates that the meeting must have been “brief and superficial,” given the barriers of language, age, and demeanor that separated them.

Both men did some of their best writing on California’s Monterey Peninsula, though at different times, and may have met there in the late 1940s.

Steinbeck died in 1968 at 66, and Moberg, who was born in 1898, committed suicide in 1973. But one thing is certain. If they were alive today both men would be deeply disturbed by the global refugee crisis and the resurgent nativism that has nurtured anti-immigration movements in Sweden, the United States, and across Europe. While Steinbeck focused on a family of Oklahoma tenant farmers driven west by natural catastrophe and Depression economics, Moberg followed a family of Swedish farmers who abandon the stony soil of Smaland in the 1800s for the promised land of rural Minnesota. Both took sides in parallel stories of epic struggle—for survival, dignity, and a place to call home. In each case, the dream of land and domicile motivated migration across states or seas by displaced souls, described most poignantly in the African American spiritual “Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child.”

Both took sides in parallel stories of epic struggle—for survival, dignity, and a place to call home.

When Vilhelm Moberg came to California in 1948, the Monterey Peninsula was about to face its own disaster—the depletion of the sardine population through over-fishing predicted by John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts, who died the year Moberg arrived. Gustaf Lannestock, a Swede who had worked as a masseur at the Hotel Del Monte and moved to Carmel, met Moberg walking on the beach and became his friend and translator. In 1998, the late Monterey County Herald columnist Bonnie Gartshore described the fateful encounter: “One day in 1948, Vilhelm Moberg, Sweden’s foremost novelist, took a rest from writing “Utvandrana” (“The Emigrants”). He had come to the Monterey Peninsula after long months of research to write the book, first of a [quartet] about Swedish families . . . in the 1800s. One way of relaxing after intense writing stints was to plunge into the surf at Carmel Beach.’’

Moberg came to the Monterey Peninsula to write a book about Swedish families in the 1800s.

When Steinbeck lived in Pacific Grove in the 1930s he sought relief in the same fashion, exploring the tide pools with his friend Ricketts and gaining a sense of proportion. Lannestock and his wife Lucile enjoyed Swedish-style entertaining and their home attracted a party crowd, described by Liljestrand as the “cultural elite in Carmel,” that included Ricketts—who wrote of his friendship with Lannestock—and Steinbeck, as well as Robinson Jeffers. But according to Moberg, notes Liljestrand, the Lannestocks “didn’t socialize much with Steinbeck” because “they took his estranged wife’s side” when the Steinbecks moved to Los Gatos and their marriage collapsed. Steinbeck’s career eventually took him to Hollywood, Mexico, and Manhattan. He completed East of Eden, the California saga of his mother’s Irish-immigrant farm family, in New York. Moberg—who based his quartet of Swedish emigrant novels on the diaries of a Minnesota farmer—had finished the first two (shown here) in Carmel by 1952, the year East of Eden appeared.

When war came, neither Moberg nor Steinbeck was afraid to speak out. Moberg was openly critical of Sweden’s attempt at neutrality, and his 1941 novel Ride This Night, though set in the 17th century, is clearly a commentary on Nazi aggression. Steinbeck’s 1942 novella The Moon Is Down is about the invasion of an unnamed town in Scandinavia by an unnamed army that is unmistakably German. The book was outlawed in occupied Sweden, where Steinbeck had friends, but contraband copies were passed by hand and Steinbeck’s contribution to European morale was cited when he received the Nobel Prize from the Swedish Academy. The Steinbeck-Moberg connection can also be seen in Arvid and Robert, characters in The New Land who, as the film critic Terrence Rafferty observed, “have come to resemble Lennie and George, the wanderers of John Steinbeck’s ‘Of Mice and Men’” in the 1972 motion picture adaptation of the second novel in Moberg’s emigrant series. The movie’s director was Jan Troell, a Swede who shared Steinbeck and Moberg’s vision of the emigrant experience—and who came to the Monterey Peninsula in 1974 to shoot Zandy’s Bride, also starring Liv Ullman.

When war came, neither Moberg nor Steinbeck was afraid to speak out.

Swedes are supposed to be solitary types who wait for others to break the ice, a function frequently served by friends like Lannestock and Ricketts, Moberg’s likely entrée to Steinbeck’s world. “According to Lannestock’s memoir,” notes Liljestrand, “Moberg’s English wasn’t very good. He mostly hung out with just the Lannestocks, with whom he spoke Swedish.” If Bonnie Gartshore is correct, Moberg made his way despite that obstacle. In Monterey, she says, “he enjoyed talking to Sicilian Fishermen whom he met on Fisherman’s Wharf, and he wrote an article about them for a Stockholm newspaper.” Devastated by the death of Ricketts and a second failed marriage, Steinbeck returned to Pacific Grove in 1949 to recover. Given their habit of taking walks, a meeting with Moberg could have occurred by accident. Given their reticence, it might have needed help.

Lannestock and Ricketts were Moberg’s likely entrée to Steinbeck’s world.

Like Steinbeck, Moberg enjoys an enduring reputation in the homeland he both criticized and celebrated in his writing. His novels are required reading in Sweden, where he’s revered as a journalist, historian, and playwright with more than two dozen dramas to his credit. Also like Steinbeck, he experimented with literary forms. Steinbeck will always be associated with Okie migration and intercalary structure for The Grapes of Wrath. The author who called The Emigrants series his “documentary novels” became synonymous with Swedish immigration to the United States. Neither writer was satisfied by the celebrity. In a letter to Toby Street, Steinbeck talked about “a longing for extinction” caused by the conviction he “had no home, never did”—cruelly ironic from one who, like Moberg, wrote so memorably of people searching for a home.

Neither Steinbeck nor Moberg was satisfied by the celebrity they achieved.

Like Steinbeck, Moberg suffered from depression that grew worse with age. A radical democrat and political contrarian, he continued to speak out against monarchy, bureaucracy, and public corruption after he returned to Sweden. But he experienced writer’s block and his melancholy became despair. Early one morning in 1973 he left a letter of apology for his wife and drowned himself. “The time is twenty past seven; I go to search in the lake for eternal sleep. Forgive me, I could not endure,” he wrote her. He is frequently paired with his fellow Scandinavian O.E. Rolvaag, the author of Giants in the Earth. But he had much in common with his fellow Californian, John Steinbeck. The connection is overlooked, but it extended to war, depression, and epic protest against epic injustice. In light of current events, it’s worth remembering.

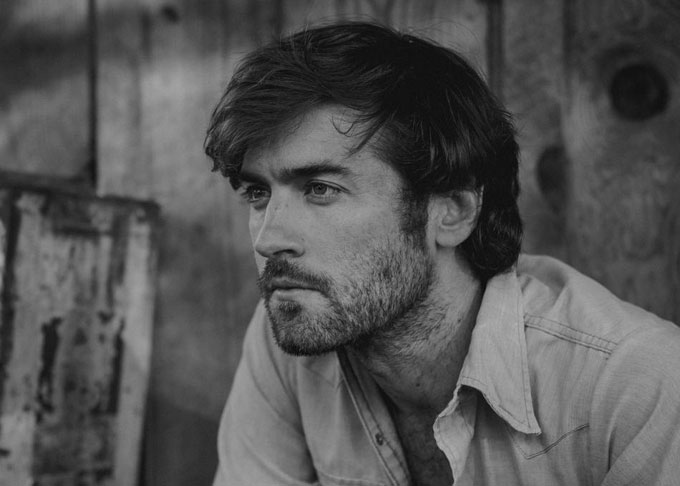

Looks Like Tom Joad and Sings Like Woody Guthrie

John Craigie speaks from experience about the title of his recently released tour recording John Craigie Live: Opening for Steinbeck. The soft-spoken West Coast singer-songwriter explains that performing as a warm-up act is like “having to read a short story by another author before getting to a work by John Steinbeck,” an artist who understood the perils of playing second fiddle. A born-and-bred Californian with the face of a sweet Tom Joad and the voice of a young Woody Guthrie, Craigie combines folk music, stand-up comedy, and situational storytelling to elicit the kind of audience response espoused by Steinbeck from listeners—to judge from the live recording—who are with him all the way on the perils of presidents named Trump and books named Leviticus. “The storytelling enables listeners to relate,” says Craigie, who majored in math at UC-Santa Cruz and got his start singing and playing in a band called Pond Rock. “Really good music doesn’t make you feel good,” he adds, echoing John Steinbeck on why he wrote fiction. “It makes you feel like you’re not alone.” Sample the track, then buy a signed CD of John Craigie Live: Opening for Steinbeck. (Photo of John Craigie by Bradley Cox)

John Craigie speaks from experience about the title of his recently released tour recording John Craigie Live: Opening for Steinbeck. The soft-spoken West Coast singer-songwriter explains that performing as a warm-up act is like “having to read a short story by another author before getting to a work by John Steinbeck,” an artist who understood the perils of playing second fiddle. A born-and-bred Californian with the face of a sweet Tom Joad and the voice of a young Woody Guthrie, Craigie combines folk music, stand-up comedy, and situational storytelling to elicit the kind of audience response espoused by Steinbeck from listeners—to judge from the live recording—who are with him all the way on the perils of presidents named Trump and books named Leviticus. “The storytelling enables listeners to relate,” says Craigie, who majored in math at UC-Santa Cruz and got his start singing and playing in a band called Pond Rock. “Really good music doesn’t make you feel good,” he adds, echoing John Steinbeck on why he wrote fiction. “It makes you feel like you’re not alone.” Sample the track, then buy a signed CD of John Craigie Live: Opening for Steinbeck. (Photo of John Craigie by Bradley Cox)

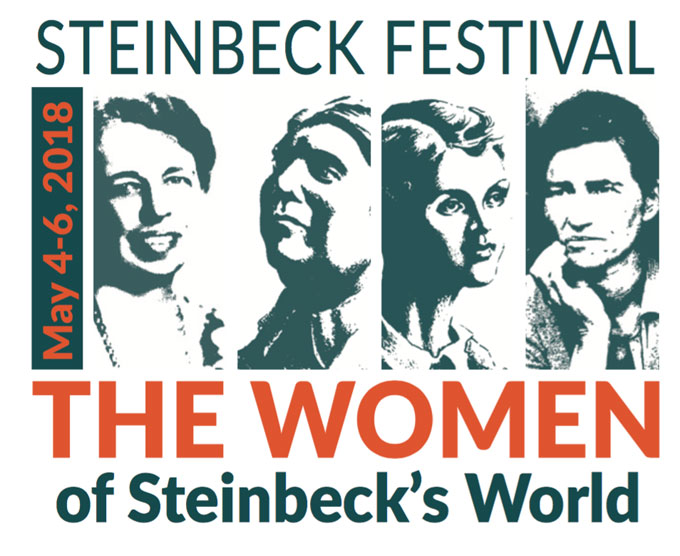

2018: Year of the Women in The World of John Steinbeck

Three sisters. Three wives. Three novels with female characters who are larger than life. Inspired by Ma Joad’s enduring example in The Grapes of Wrath, this year’s Steinbeck Festival will celebrate the women in John Steinbeck’s life and fiction over three days in May, at three venues associated with women Steinbeck cherished or invented. Sponsored by the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California, the festival opens on Friday, May 4, and features an afternoon of seminars at Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Center in Pacific Grove—where Steinbeck and his sister Mary studied biology as undergraduates—tours of the nearby “Doc” Ricketts lab where female visitors from Dora Flood’s place were always welcome in Cannery Row, and a full day of speeches and fun in the town where Steinbeck was a born and grew up, a slightly spoiled only son, and Cathy runs her brothel in East of Eden, without Dora’s kindness, Ma Joad’s goodness, or the nurturing instinct of Steinbeck’s mother, sisters, and wives (save one). Speakers include Richard Astro, the author of John Steinbeck and Edward F. Ricketts; Mimi Gladstein, an expert on women in American fiction and the author of a study of Steinbeck’s female characters with the intriguing title “Maiden, Mother Crone”; and Susan Shillinglaw, director of the National Steinbeck Center and author of Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage. A full schedule of events and information about tickets and logistics can be found on the National Steinbeck Center’s festival page.

An Essential History of John Steinbeck’s American West

Like Jackson Benson’s 1980 biography of John Steinbeck, the essential book on Steinbeck’s storied life, David Wrobel’s new history of the American West in Steinbeck’s formative period is an essential read for fans of the writer whose fiction brought the region to life for audiences everywhere. Designed for use by students and published by Cambridge University Press as part of the Cambridge Essential Histories series, America’s West: A History, 1890-1950 is compact, comprehensive, and compelling, organizing facts and creating patterns the way Steinbeck did in The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden, historical novels written in part to educate readers about movements of people, power, and ideas that made the American West first a beacon, then a bellwether, and finally a warning. Like Steinbeck, Wrobel presents the region’s history as a morality play we’re invited to watch about the sins of exceptionalism, expansionism, and economic domination.

Like John Steinbeck, David Wrobel presents the region’s history as a morality play we’re invited to watch about the sins of exceptionalism, expansionism, and economic domination.

Steinbeck’s history in this regard began before he was born. The economic cycles and social problems of of the 1890s affected his young parents, who settled in Salinas, where he was born in 1902, the year Teddy Roosevelt became president. The remedies for Gilded Age corruption put in place under Roosevelt, a New York blue blood who reinvented himself as a Dakota cowboy, brought good government to Washington and new attention to the West. Places like Salinas prospered, but they typified the paradox of progressive politics in America between the two Roosevelts. The same movement that broke up corporate monopolies, created national parks, and enfranchised women also imposed draconian social controls, including Prohibition, union-busting, and mass deportation. The Red Peril paranoia that became federal policy following World War I eventually led Salinas to experiment with what Steinbeck called fascism. He tore up the novel he wrote about the militarization of local government during a strike by lettuce workers, but by 1935 he had discovered his subject and set his course, reporting on migrant labor for the San Francisco News and writing The Grapes of Wrath, the protest novel that put into words the suffering and shame shown in Dorothea Lange’s photographs of migrant mothers and children.

Steinbeck tore up the novel he wrote about the militarization of local government during a strike by lettuce workers, but by 1935 he had discovered his subject and set his course.

Roosevelt progressivism at both ends of the period covered in America’s West gave Steinbeck the ideals, and events in California the ideas, expressed in The Grapes of Wrath. His upbringing in Salinas gave him the sense of empathy for people, animals, and nature that sympathetic readers recognize and respond to on first reading. When examining the beliefs and behaviors at work in the background, however, it’s also helpful to understand the sense of detachment from events and emotions he had to develop, with changes of subject and venue, in the novel’s aftermath. When he wrote about marine biology or war or the history behind the legend of King Arthur, he had the benefit of distance from his personal past and perceptions. Europeans since De Tocqueville have written about the United States with the same outsider’s advantage that Steinbeck enjoyed in England and David Wrobel has in writing about Steinbeck’s America.

Europeans since De Tocqueville have written about the United States with the same outsider’s advantage that Steinbeck enjoyed in England and David Wrobel has in writing about Steinbeck’s America.

A native of London with a yen for America, David Wrobel brought his coals to Newcastle by enrolling at Ohio University, where he immersed in Steinbeck under Robert DeMott and received his PhD in American studies. His understanding of the history behind The Grapes of Wrath and the intellectual currents of Steinbeck’s time has benefited immensely from his tenure at Oklahoma University, where he teaches, researches, and writes about Steinbeck and the American West and was recently appointed acting dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Oklahoma and California are his coordinates and Steinbeck is his moral compass in the case he makes for America’s West to 1950, the first of two volumes planned by Cambridge University Press. He has the English virtue of readability, along with Steinbeck’s eye for victims and losers, and Cambridge University Press designed the book to last, with just enough charts and graphs and not too many footnotes, placed at the bottom of the page where they belong. Its value is enhanced for followers of Steinbeck’s thinking by the author’s focus on the hidden costs of the West’s ascendancy and the line leading from the triumphalism of the past to the politics of the present. Five stars.

A native of London with a yen for America, David Wrobel brought his coals to Newcastle by enrolling at Ohio University, where he immersed in Steinbeck under Robert DeMott and received his PhD in American studies. His understanding of the history behind The Grapes of Wrath and the intellectual currents of Steinbeck’s time has benefited immensely from his tenure at Oklahoma University, where he teaches, researches, and writes about Steinbeck and the American West and was recently appointed acting dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Oklahoma and California are his coordinates and Steinbeck is his moral compass in the case he makes for America’s West to 1950, the first of two volumes planned by Cambridge University Press. He has the English virtue of readability, along with Steinbeck’s eye for victims and losers, and Cambridge University Press designed the book to last, with just enough charts and graphs and not too many footnotes, placed at the bottom of the page where they belong. Its value is enhanced for followers of Steinbeck’s thinking by the author’s focus on the hidden costs of the West’s ascendancy and the line leading from the triumphalism of the past to the politics of the present. Five stars.

The cover illustration is Thomas Hart Benton’s 1928 Western Regionalist painting “Boomtown.” Of special interest is the section on the Great Depression and the demographic shifts, racial divisions, and labor unrest dramatized in The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, and In Dubious Battle. It recalls the contributions made to the cause by Steinbeck’s co-workers Dorothea Lange, Carey McWilliams, and Pare Lorentz and explains the epic campaign of Upton Sinclair for governor in 1934 against the same forces that later waged war on The Grapes of Wrath. The author’s essay on California social protest literature, Steinbeck, Sinclair, McWilliams, and the WPA Guide to California appears in American Literature in Transition: The 1930s, an anthology edited by Ichiro Takayoshi.

The cover illustration is Thomas Hart Benton’s 1928 Western Regionalist painting “Boomtown.” Of special interest is the section on the Great Depression and the demographic shifts, racial divisions, and labor unrest dramatized in The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, and In Dubious Battle. It recalls the contributions made to the cause by Steinbeck’s co-workers Dorothea Lange, Carey McWilliams, and Pare Lorentz and explains the epic campaign of Upton Sinclair for governor in 1934 against the same forces that later waged war on The Grapes of Wrath. The author’s essay on California social protest literature, Steinbeck, Sinclair, McWilliams, and the WPA Guide to California appears in American Literature in Transition: The 1930s, an anthology edited by Ichiro Takayoshi.

Opposites Attract in Pursuit Of Travels with Charley

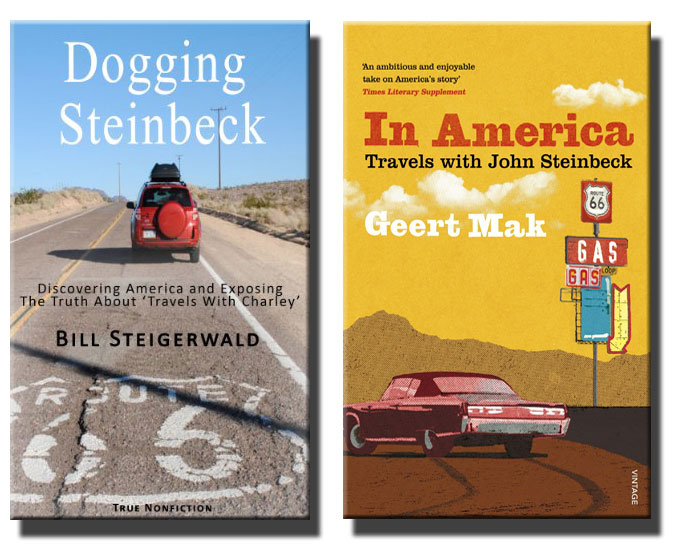

John Steinbeck delivered the speech of his life after taking the road trip described in Travels with Charley in Search of America, the last book he wrote before being awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature. Fifty-five years following Steinbeck’s acceptance speech in Stockholm, a pair of journalists who retraced Steinbeck’s route across America, and wrote separate books simultaneously, came together at a literary award event in Amsterdam attended by Queen Máxima of the Netherlands and broadcast on Dutch TV. Like their books, Bill Steigerwald and Geert Mak differ in background, language, and style. But they agree on issues, including Steinbeck’s accuracy in Travels with Charley, and their accord led to friendship. Like Steinbeck’s relationship with Bo Beskow, the Swedish artist who helped arrange Steinbeck’s speech in Stockholm, it flourished despite distance, and it led to Steigerwald’s speech in Amsterdam on November 27, when Mak was awarded the 2017 Prince Bernhard Cultural Prize for lifetime achievement as Queen Máxima looked on.

Writers Celebrate Meeting on John Steinbeck’s Trail

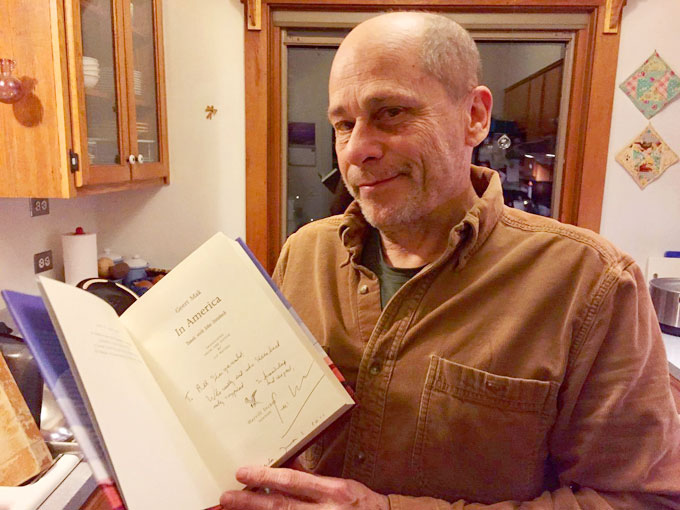

Bill Steigerwald, the investigative reporter from Pittsburgh who wrote Dogging Steinbeck “to expose the truth about Travels with Charley and celebrate Flyover America and its people six years before they elected Donald Trump,” is an American journalist with a rough edge and an independent streak. Geert Mak, the author of In America: Travels with John Steinbeck and the recipient of the award, is a Dutch journalist with European polish who writes popular history books that have drawn criticism from academics in Europe. When scholars in America downplayed or took offense at Steigerwald’s charges in Dogging Steinbeck, Mak emailed “to express my personal admiration for the job you did [and] to tell you that you became a kind of journalistic hero in my travel-story about Steinbeck.” He cited Steigerwald in the book he wrote to help readers in Europe, where John Steinbeck became a hero for writing The Moon Is Down, better understand contemporary America, where recent events have made the social criticism in Steinbeck’s American novels more relevant than ever. Mak inscribed a copy of his book to Steigerwald when it was translated from Dutch into English.

Colleague Writes Postscript to Speech in Amsterdam

The speech Bill Steigerwald gave about Geert Mak was short, like John Steinbeck’s address in Stockholm, and it left time to socialize, as Steinbeck did with Bo Beskow in 1962. The irony in this description of meeting Mak in America and paying tribute in Amsterdam sounds a bit like Steinbeck, who favored satire when he reported from Europe after World War II:

Geert Mak is my age, 70, and a masterful practitioner of drive-by journalism. In America sold a couple of hundred thousand copies in Holland, as most of his history books do. It was reviewed favorably by the Guardian newspaper, which liked both Mak’s fine writing and his left wing Euro-politics.

Mak, who calls himself a proud “half-socialist,” has visited America many times and lived for a while in Berkeley. In the fall of 2010, when he and his wife were a week into their 10,000-mile Charley road trip, in New Hampshire, he learned that I was traveling a day or two ahead of him.

Mak also soon learned I was posting a daily road blog to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and slowly revealing my charges that Steinbeck had fictionalized significant parts of Charley—which for half a century had been marketed, reviewed and taught as a nonfiction book.

Our relationship flourished online and two months ago I was suddenly asked to be a surprise guest at an elaborately produced and televised ceremony in Amsterdam honoring Mak for his impressive lifetime work. He is a household name in Holland and because he praised me in In America the people there were led to think I’m an important American journalist/author. As I wrote in an email to friends from Amsterdam after my speech, “I represented our great country with as little dignity as possible and I am proud to say that in my four-minute address—my world debut as a public speaker—I did not once bash America or use the T-word, though of course our dear leader was the embarrassing elephant in the room/country/continent.”

Mak’s prize was a crazy-looking necklace and 150,000 euros, but I was told by half a dozen people that the big hug he gave me during the event after my speech was the emotional high point of the show, which to a supposed hard boiled ex-newspaperman like me is a hilarious thought.

The American mode of mocking humor started with Mark Twain, the American drive-by journalist who invented “creative nonfiction,” and the idea of Innocents Abroad, when he wrote about his first trip to Europe. Thanks to Bill Steigerwald’s dogged pursuit, Travels with Charley has now been reassigned to the in-between category pioneered by Mark Twain 150 years ago. Thanks to Steigerwald’s long distance friendship with Geert Mak, Steinbeck was on stage again at another award event in Europe held to honor the achievements of a popular writer with mixed feelings about America.

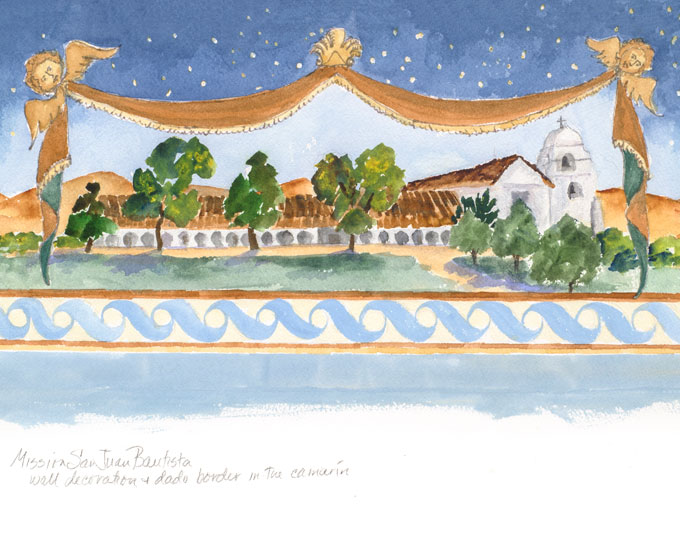

Mission Art by Nancy Hauk Mirrors Steinbeck’s History

An exhibition of art in the California mission town of San Juan Bautista by the late Nancy Hauk, whose home in Pacific Grove was once the residence of the man Steinbeck mythologized as “Doc,” will have special meaning for readers curious about the history behind Steinbeck’s California fiction. Thirty years before Steinbeck was born to the west, in Salinas, voters in eastern Monterey County, including the Mexican Californians of San Juan Bautista and Yankee settlers in Hollister, were promised their own county if Salinas became the seat of Monterey County instead of Monterey, the mission town that was California’s first capital. One outcome of this political decision was the emotional geography that came to define Steinbeck’s social sympathies and sense of place. Salinas boomed, Monterey languished, and in 1874 the County of San Benito was born, named for the river the Spanish called after St. Benedict when they built the mission they named for John the Baptist. Hollister, the nearby town where Steinbeck’s father’s family farmed and raised five sons, became San Benito’s county seat.

Steinbeck’s mother’s family lived in Salinas before the county split, and she returned to live there with her husband in 1900. He became Monterey County treasurer following a political scandal. She became the kind of local activist who took sides on civic issues like the vote of 1874. Their son’s feelings about Salinas ran in the opposite direction and eventually became material for his writing. The family’s cottage in Pacific Grove was a refuge from Salinas when Steinbeck needed one, and the Hauk house where “Doc” Ricketts once lived is nearby. So is the Monterey lab that attracted artists, misfits, and other characters celebrated by Steinbeck in his Cannery Row fiction. The conflict between Salinas and Monterey epitomized in the San Benito vote 50 years earlier was emblematic of a deeper division explored in East of Eden, the book Steinbeck wrote for his sons. Steinbeck’s art reflected his sympathies in this fight and caused controversy. Nancy Hauk’s art reminds us of the history behind the fiction.

Steinbeck’s mother’s family lived in Salinas before the county split, and she returned to live there with her husband in 1900. He became Monterey County treasurer following a political scandal. She became the kind of local activist who took sides on civic issues like the vote of 1874. Their son’s feelings about Salinas ran in the opposite direction and eventually became material for his writing. The family’s cottage in Pacific Grove was a refuge from Salinas when Steinbeck needed one, and the Hauk house where “Doc” Ricketts once lived is nearby. So is the Monterey lab that attracted artists, misfits, and other characters celebrated by Steinbeck in his Cannery Row fiction. The conflict between Salinas and Monterey epitomized in the San Benito vote 50 years earlier was emblematic of a deeper division explored in East of Eden, the book Steinbeck wrote for his sons. Steinbeck’s art reflected his sympathies in this fight and caused controversy. Nancy Hauk’s art reminds us of the history behind the fiction.

“Paintings of the California Missions,” an exhibition of work by Nancy Hauk (in photo), includes the Mission San Juan Bautista image shown here. The show has been extended and will run through May 2018.