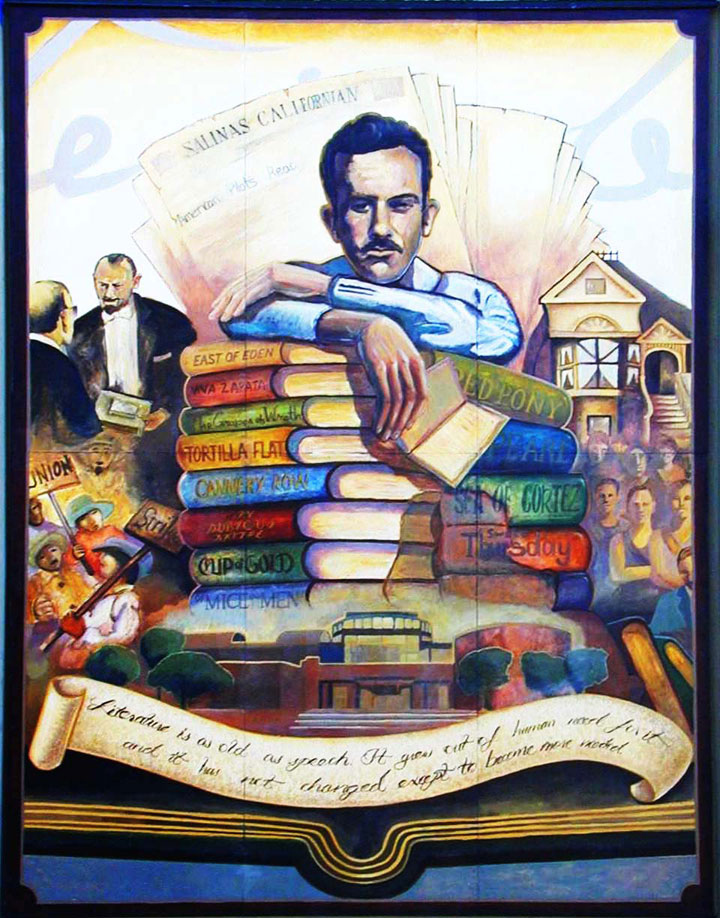

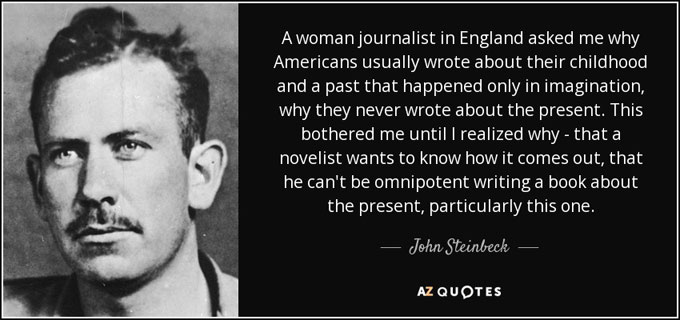

The long relationship between Playboy magazine and Donald Trump, America’s playboy-in-chief, is old news. But the recent death of Hugh Hefner unearthed some surprising Playboy connections, including a list of major authors—among them John Steinbeck—who wrote for the serious men’s magazine that paid well and reached readers otherwise untouched by serious literature. In light of our president’s tweets and threats to bomb America’s enemies back to the Stone Age, Steinbeck’s satirical “Short Short Story of Mankind,” first published in the April 1957 issue of Playboy, has a message as relevant today as it was 60 years ago, when the golf-loving Dwight Eisenhower was president and the Cold War was on in earnest.

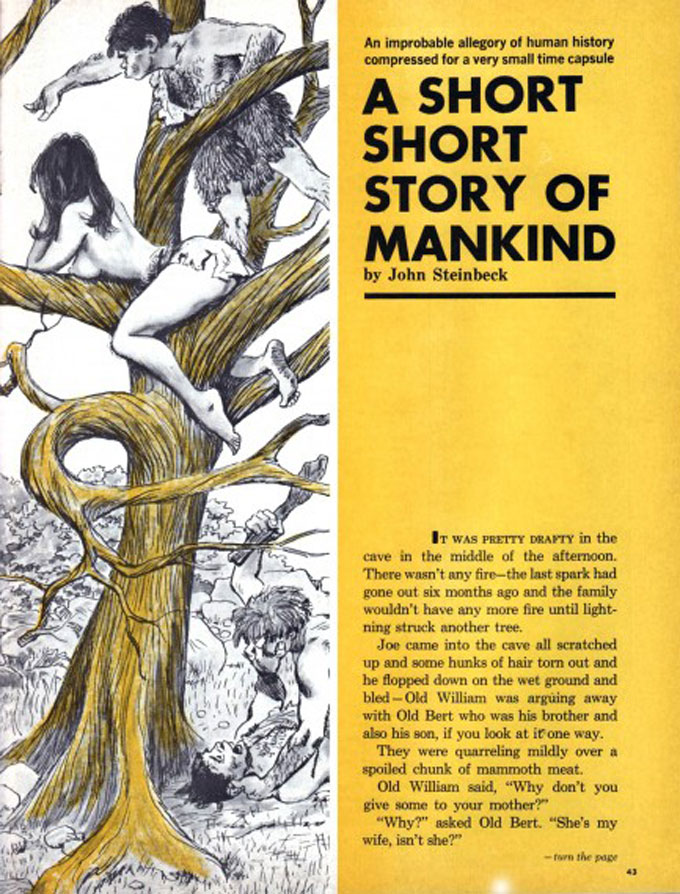

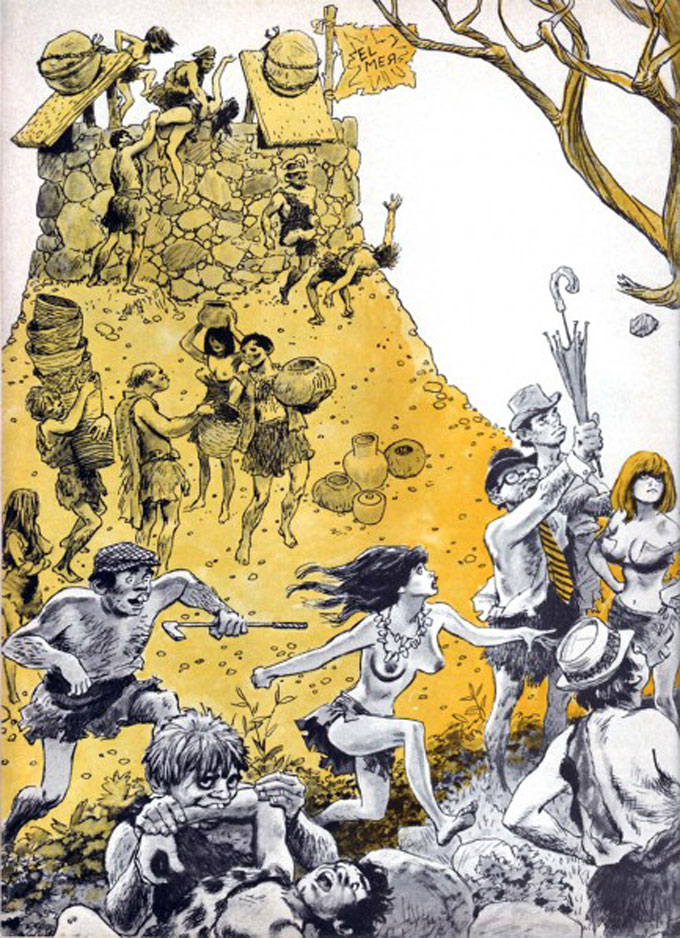

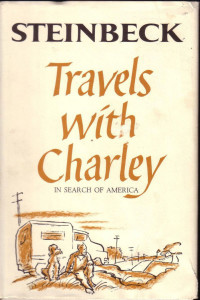

An allegory in the style of Mark Twain, Steinbeck’s account of human progress from savagery to civilization has a cartoon quality picked up by the illustrator for Adam, which republished Steinbeck’s Playboy piece in 1966 (images above and below). But like the “poisoned cream puff” of Steinbeck’s Cannery Row fiction, the mirth of “A Short Short Story of Mankind” is meant to be sobering. At every step, Steinbeck suggests, our progress as a species has faced resistance from a constant and terrifying tribal stupidity which, unchallenged, would lead to our extinction. “It’d be kind of silly if we killed our selves off after all this time,” he concludes. “If we do, we’re stupider than the cave people and I don’t think we are. I think we’re just exactly as stupid and that’s pretty bright in the long run.”

To my knowledge “A Short Short Story of Mankind” has never been anthologized, but it’s time it was. Living in the daily shadow of Donald Trump’s presidency, we need its dark warning and its ray of hope, the somber and uplifting counterpoint that echoes Steinbeck’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech and later writing. Today, six decades after Playboy magazine published John Steinbeck for the first and only time, it’s useful to remember that the author died a month after the election of Richard Nixon, whose dishonesty and demagoguery he deeply distrusted. It’s easy enough to imagine what he’d have to say about Donald Trump if he were still alive. The warning he’d have for a nation under Trump is implicit in the imagery and tone of his Cold War admonition to America under Eisenhower—an incurious president who also preferred golf but, unlike Trump, read the occasional book and avoided Stone Age rhetoric. Read the piece and judge for yourself.