The forced internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans two months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor distressed John Steinbeck, who admired Franklin Roosevelt, the president who signed the internment order. Today, exactly 75 years later, the memory of Executive Order 9066 continues to burden American history. An anniversary article on the World War II internment of Japanese Americans in the January 2017 issue of Smithsonian Magazine leads off with a profile of Jane Yanagi Diamond, a vibrant internment survivor I happen to know.

The 1942 photograph taken by Steinbeck’s ally and contemporary Dorothea Lange (above) shows Jane as a sorrowing child holding on to her pregnant mother’s hand, moments before the Yanagi family boards a bus on the way to the emergency assembly center hastily set up by the federal government at a California racetrack. The family was then sent to Topaz, an internment camp in Utah that would also house two exceptional California artists, Chiura Obata and George Matsusaburo Hibi. Obata, an art instructor at UC Berkeley, and Hibi, a prolific painter from Hayward, California, founded an art school at Topaz that uncovered hidden talent and helped internees cope until the war ended and they could go home.

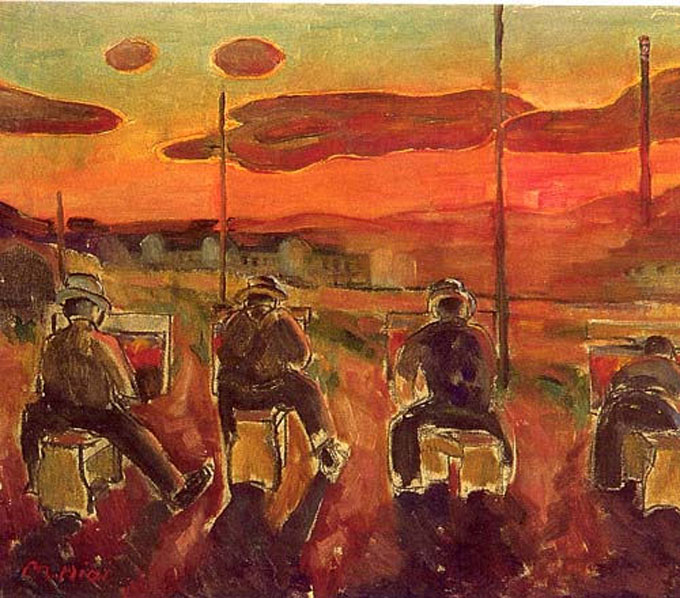

Obata eventually returned to his teaching post at Cal and became famous for his Yosemite scenes. Hibi’s paintings included internment camp scenes like the one shown here. He was also magnanimous, donating 50 of his and his family paintings to the Hayward community before being sent to Topaz. Michael Brown, the author of Views from Asian California – 1920-1965, quotes Hibi as saying this about the gift: “There is no boundary in art. This is the only way I can show my appreciation to my many American friends here.’’ Obata died in 1975, Hibi in 1947, two years after his release from Topaz.

How Creating Art Helped Japanese Americans Survive

Obata and Hibi were part of a remarkable art movement in the Japanese American camps, most of which included professional artists who realized the importance of establishing a creative outlet for the internees. The work they produced–both professionals and students–was so moving, so powerful that in 1992 the Japanese American National Museum, the Wight Art Gallery at UCLA, and UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center assembled a landmark traveling exhibition, “The View from Within: Japanese American Art from the Internment Camps 1942-1945.” Hibi’s colorful painting of four Topaz internees seated at easels is testimony to the spirit of the movement he and Obata helped create.

Obata and Hibi were part of a remarkable art movement in the Japanese American camps, most of which included professional artists who realized the importance of establishing a creative outlet for the internees.

I was a reporter at the time, and I wrote several articles about the exhibition. My interest was initially stirred when I learned that a Japanese American artist named Miki Hayakawa was taken from my town of Pacific Grove, California, to an internment camp in Santa Fe, New Mexico. I knew Hayakawa was a superb artist because several of her exquisite paintings had come into the art gallery that my wife Nancy and I owned there. Hayakawa lived in Pacific Grove from 1939 until her removal to the camp and may well have known—or known of—John Steinbeck, who was in Pacific Grove off and on during that period. Hayakawa died in Santa Fe in 1953.

I was a reporter at the time, and I wrote several articles about the exhibition, ‘The World From Within: Japanese American Art from the Internment Camps, 1942-1945.’

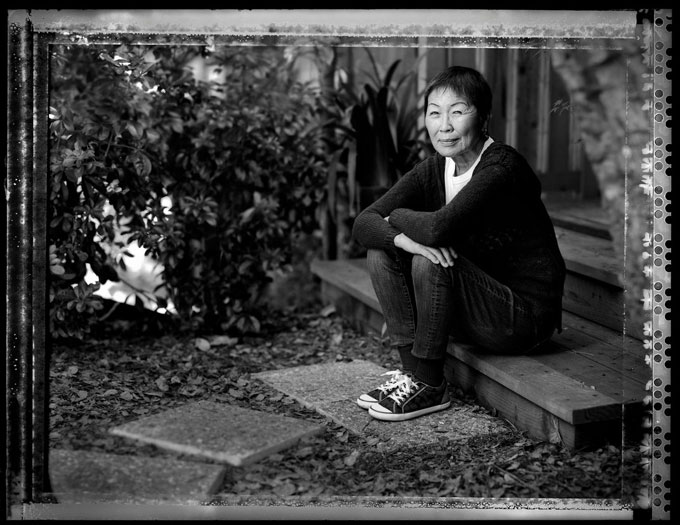

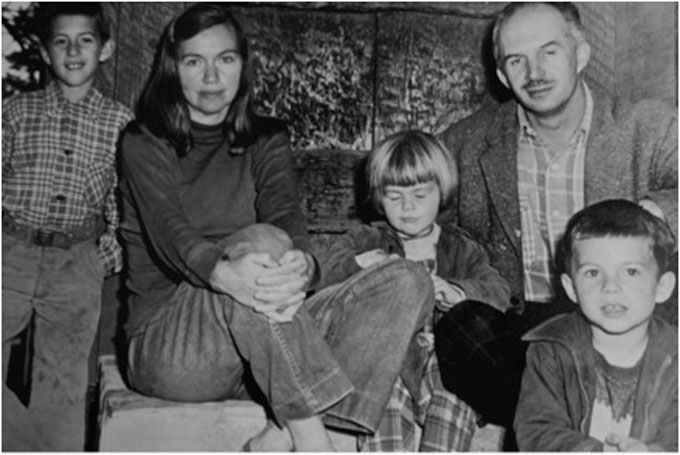

I met Jane Yanagi Diamond (shown above at home) several years ago when she and her husband Tony came into the gallery. They live in Carmel and had a painting by Hibi that had hung at Topaz and that Hibi gave to Jane’s father when the family was released. Jane wanted to find a good home for the work and together we decided that it should return to Topaz, where a museum had been established to memorialize the internment of Japanese Americans like Jane. The piece was dramatic. Painted on four panels, it depicts three tigers stalking a brave antelope or gazelle, head down, determined to hold its ground in the face of an approaching threat. I wondered at the time if Hibi painted it to give children like Jane the courage they needed to go on.

I met Jane Yanagi Diamond when she and her husband Tony came into the gallery. They live in Carmel and had a painting by Hibi that had hung at the Topaz camp.

Jane developed a love of art, favoring the freedom of California plein air painting—work painted out of doors in an Impressionistic manner—and attending frequent art openings in and around Carmel with her husband. When an exhibition of Nancy’s paintings opened at the Pacific Grove Library several years ago, Tony and Jane were there. She recently shared a story about her father. “After Topaz,” she said, “whenever my father would get angry about something–sometimes something I might have done–I could always redirect his anger by mentioning Franklin Roosevelt because it brought back memories.”

Jane developed a love of art, favoring the freedom of California plein air painting and attending frequent art openings in and around Carmel with Tony. She recently shared a story about her father.

The Yanagi family also had the three tigers and the gazelle to help them hold onto a piece of personal history made less painful by art. But Hibi’s painting has now returned to Topaz, where it will continue to tell the story of artful courage and coping from a troubling episode in American history.

Photograph of Jane Yanagi Diamond by Paul Kitagaki Jr. courtesy Smithsonian Magazine.