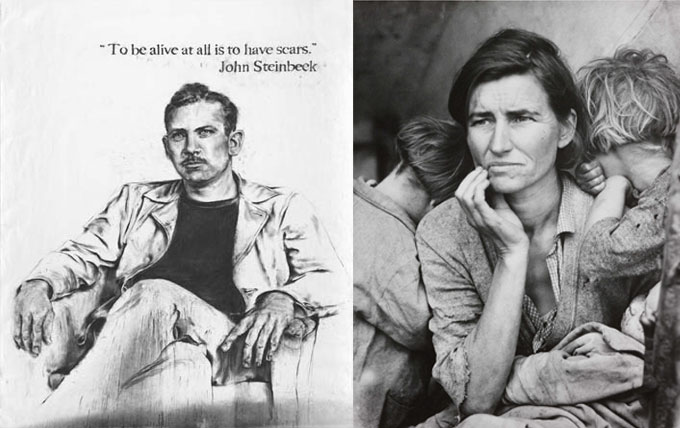

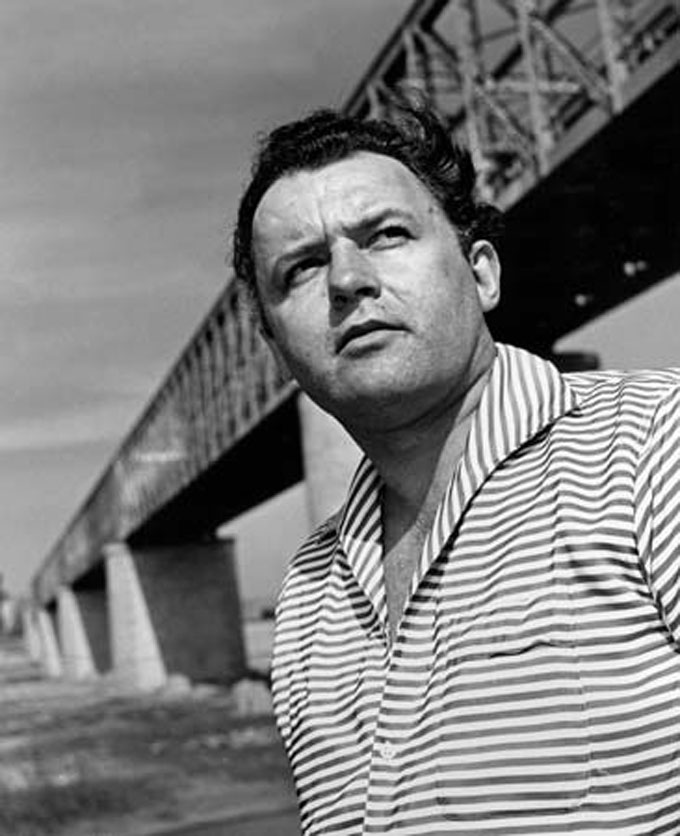

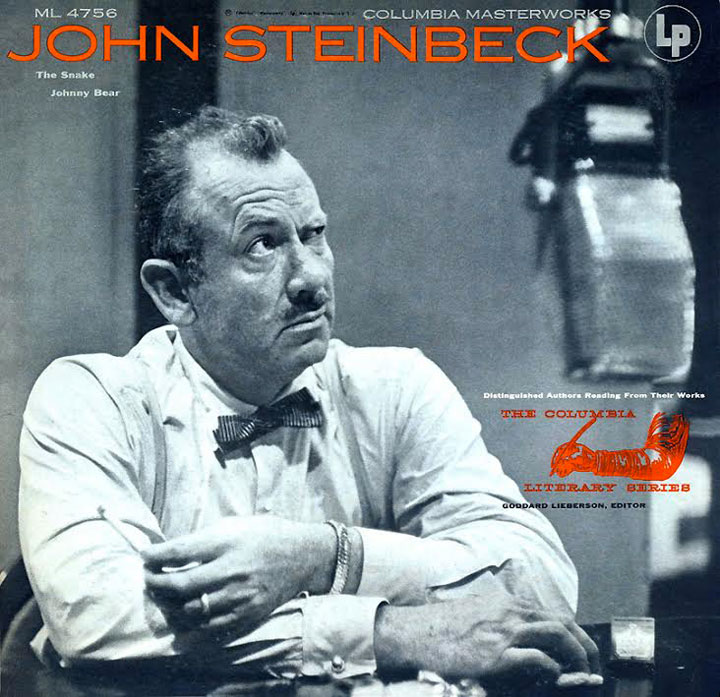

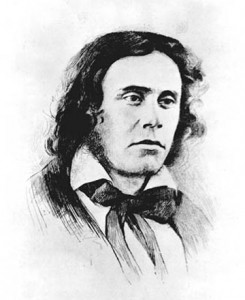

John Steinbeck knew Dorothea Lange, the iconic Depression-Era photographer who documented the plight of itinerant farm workers like Steinbeck’s Joads, and Lange’s images illustrated the cover of Their Blood Is Strong, the collection of columns Steinbeck wrote about migrants in the run-up to The Grapes of Wrath. Eighty years later, Lange and Steinbeck have come together again in an unlikely place—the art collection on display at Levi’s Stadium, the $1 billion facility built recently in Santa Clara, California for the San Francisco 49ers football team. The irony of exhibiting Steinbeck’s portrait and Lange’s “Migrant Mothers” on the walls of a publicly subsidized sports palace seems lost upon the team’s owners and Santa Clara’s mayor, who resigned on February 9, hours after the 2016 Super Bowl was played at Levi’s Stadium.

The journalist Gabriel Thompson, a Steinbeck Fellow at San Jose State University, writes eloquently about the history of community organizing, and about today’s low-wage economy. An email he sent last week noted the jarring juxtaposition of Steinbeck and Lange with big-money sports on the walls of Levi’s Stadium, and it provided a link to the investigative piece he wrote for Slate about working as a food server during the Super Bowl. “The portrait hangs directly across from the office of the food service contractor that operates at Levi’s,” he said, adding that Lange’s “Migrant Mother” (originally titled “Pea Pickers”) is also on display. He included a link to a stadium PR story that makes this pitch for buying a box seat:

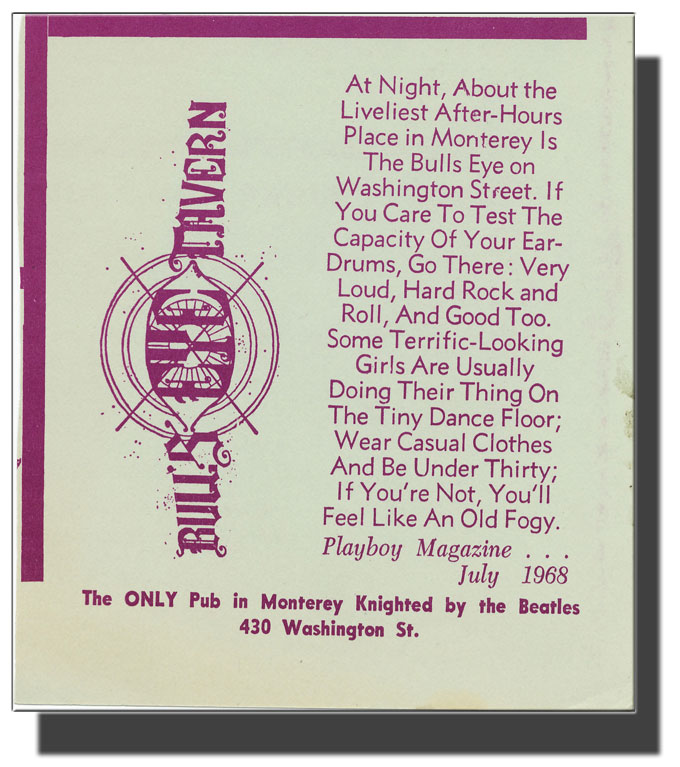

Gather 19 of your closest friends and rent a suite that gives you and your crew premium parking right next to the stadium, entry to Michael Mina’s Tailgate, upscale catering with an in-suite food and beverage credit, and access to the Trophy Club, where you’ll receive a complimentary glass of champagne and appetizers upon arrival. The suites are outfitted with comfy leather theater-style seats, Internet access and plenty of flat screen monitors to ensure you don’t miss any of the action. Prices vary by game but expect to shell out between $20,000 and $40,000 for the ultimate in VIP hospitality.

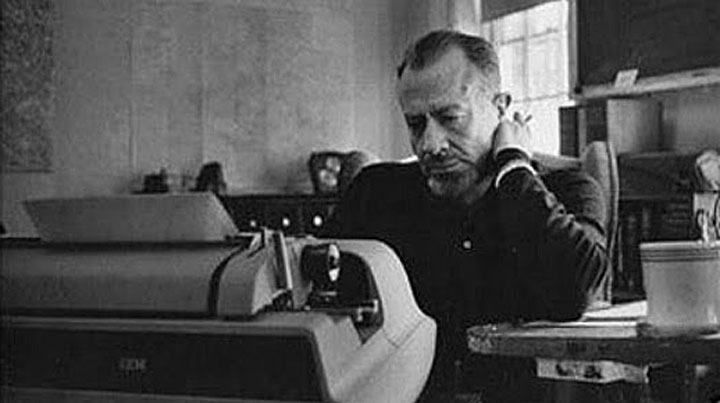

John Steinbeck, a critic of conspicuous consumption, celebrated common men and women in his writing. During college he worked for the Spreckels sugar company, which operated ranches in the rich agricultural area between King City and Santa Clara, California, south of San Francisco. Later, Santa Clara’s fragrant orchards gave way to development; today the city of 110,000 is home to tech giants including Intel, along with Santa Clara University, where a center for business ethics fronts a quiet entrance plaza anchored by the Mission Santa Clara church. Levi’s Stadium is across town, on land provided by the city not far from Intel and Mission College, a public institution. A local referendum to stop the San Francisco 49ers project failed, following a massive media and mail campaign and heavy lobbying by city leaders. According to news sources, controversy surrounding lost soccer fields—and suspicious side deals—continues to dog Santa Clara officials who went to bat for the project.

Steinbeck would recognize the present problem with Santa Clara. He wasn’t much of a sports fan, or civic booster, and his father became treasurer of Monterey County after the incumbent embezzled public funds. Today, Santa Clara residents are scratching their heads over the sudden resignation of their mayor, a former code-enforcement officer—an act, according to San Jose Mercury News columnist Scott Herhold, that disqualifies the ex-mayor from further office, “including secretary of his homeowners’ association.” According to the paper, the three women on the seven-member Santa Clara city council are asking hard questions about Levi’s Stadium, and the Hispanic city manager is complaining about racial discrimination.

Steinbeck would also recognize the unintentional irony—and the awful syntax—in another assertion, pulled from the PR piece quoted earlier, about the costly amenities at Levi’s Stadium:

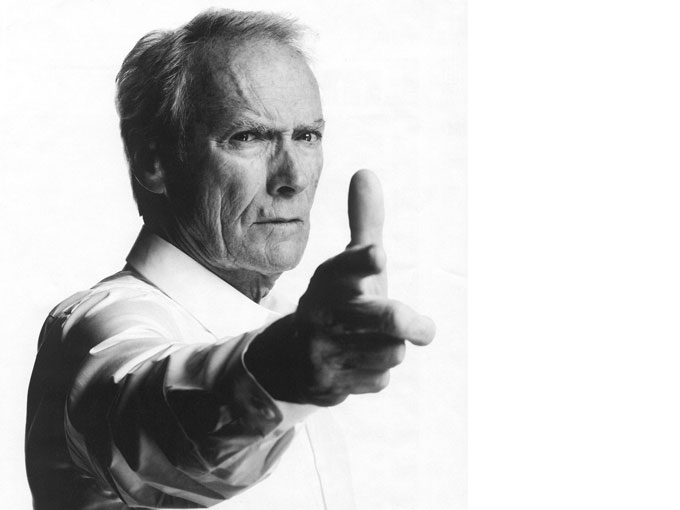

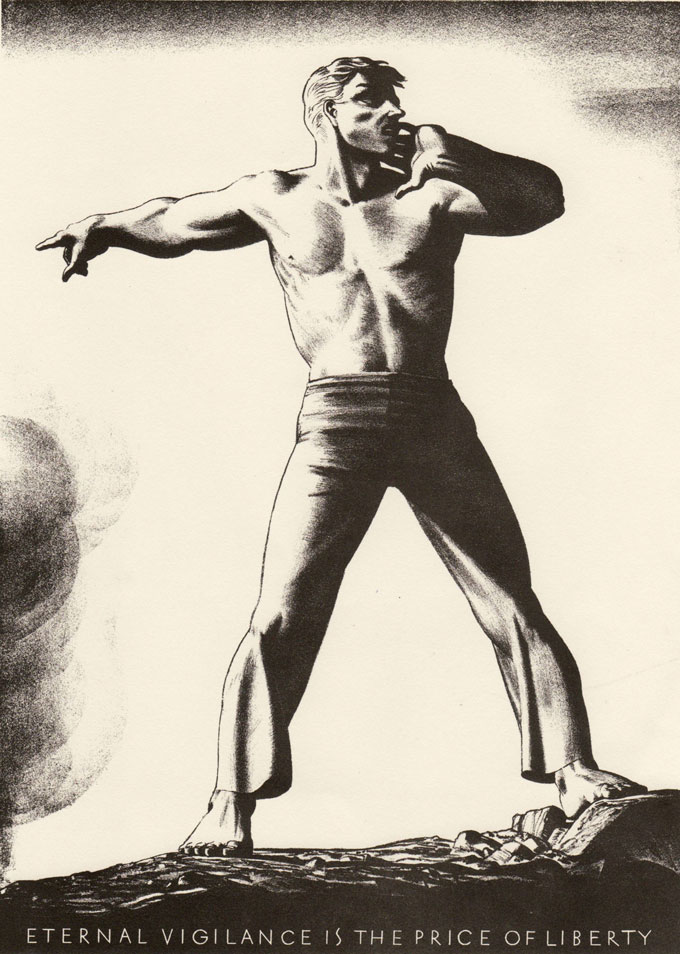

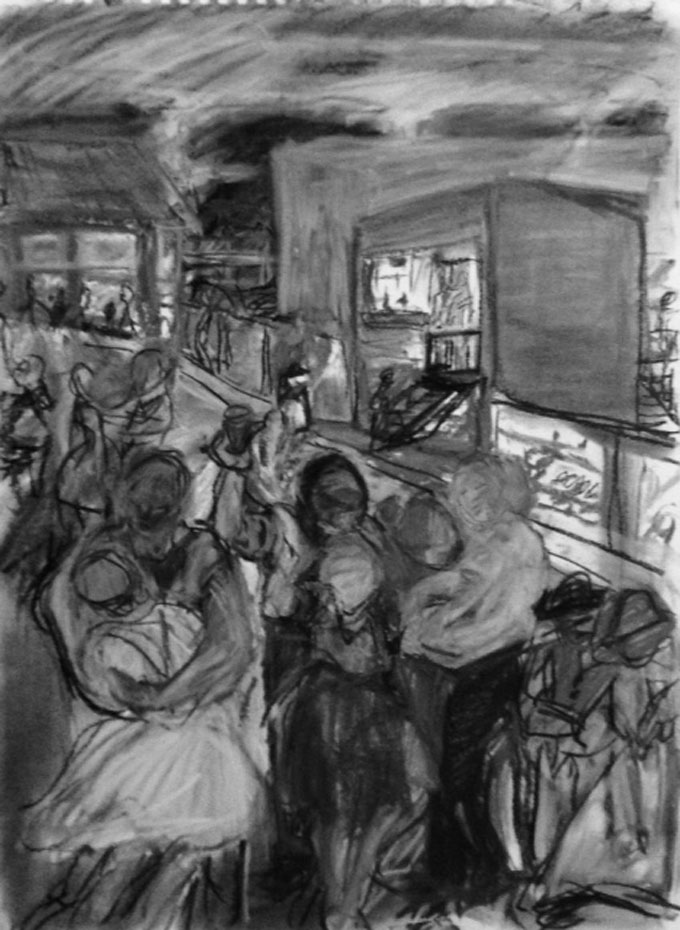

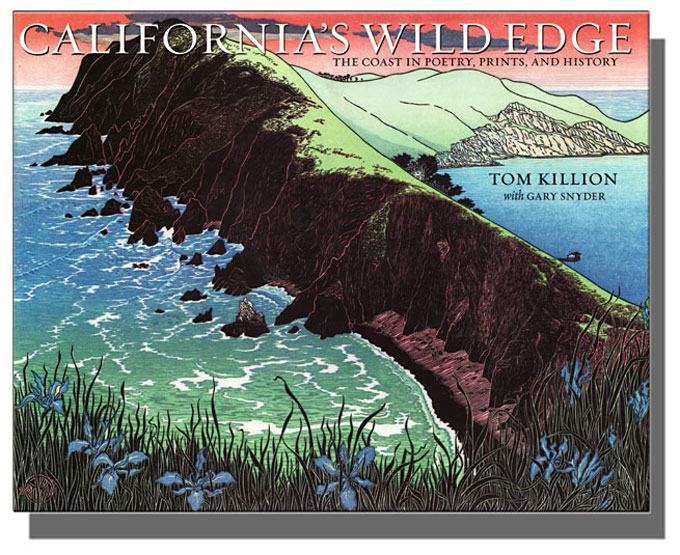

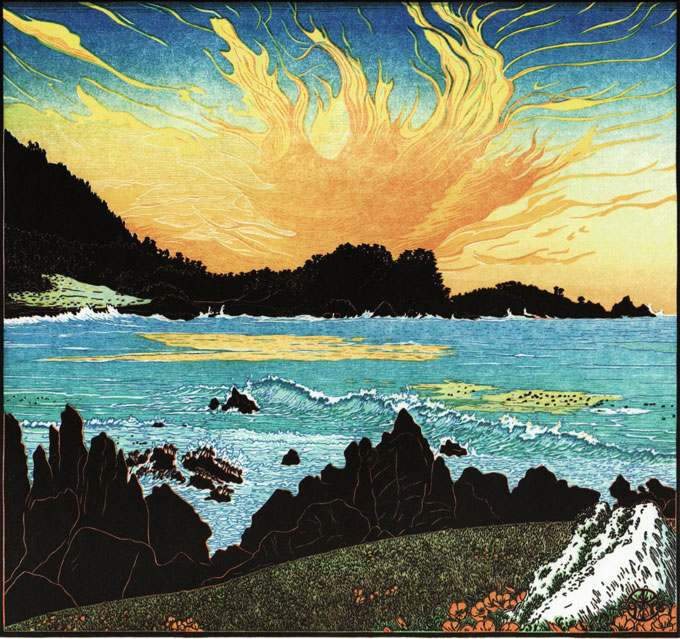

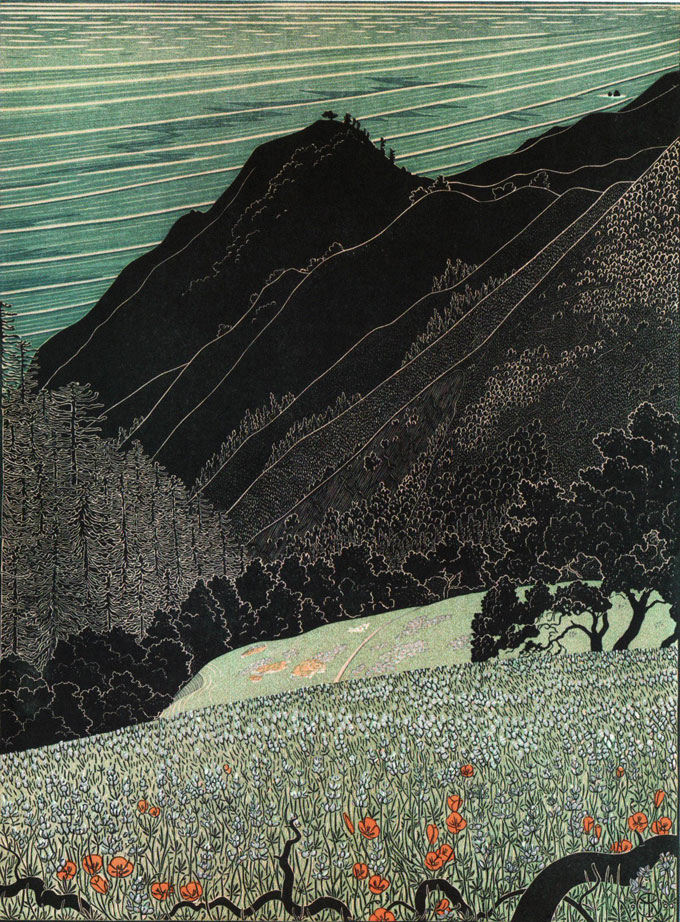

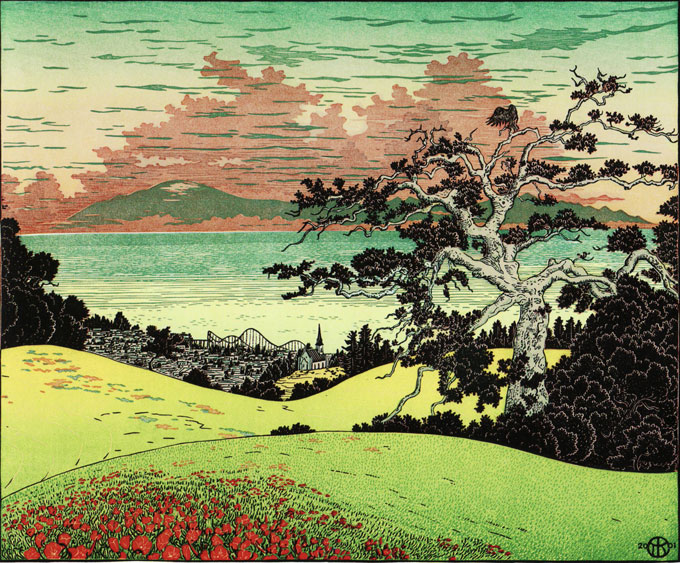

Being that this stadium is located in the most-cultured half of California, an emphasis on art is a given. Spread throughout the elite Citrix Owners Club, the Brocade Club, BNY Mellon Club East and West and SAP Tower of suites, this collection, curated by Sports and The Arts specifically for Levi’s Stadium, is comprised of over 200 pieces of original artwork and 500 photographs that celebrate the history of the San Francisco 49ers as well as California’s stunning landscape. You’ll find charcoal sketches of notable figures such as John Steinbeck and Jack Kerouac as well as timeless psychedelics of the storied Fillmore made famous by Bill Graham. However, the portraits stadium-goers still pose next to the most are those of Joe Montana throwing to Jerry Rice and current quarterback Colin Kaepernick on the run.

When the city of Salinas wanted to name a school or library for John Steinbeck, he suggested choosing a bowling alley (or whorehouse) instead. For followers of the Levi’s Stadium story from Salinas and Monterey, there’s an upside to Santa Clara’s cluelessness about Steinbeck: Cannery Row may be tacky, and the National Steinbeck Center needs money, but neither place violates the spirit of John Steinbeck and Dorothea Lange like the San Francisco 49ers’ opulent new home in Santa Clara, California, where Steinbeck and Lange hang within view of noshing VIPs, high above ordinary football fans who can’t afford a five-figure seat.

Photo of Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California by Michael Fiola (Reuters).