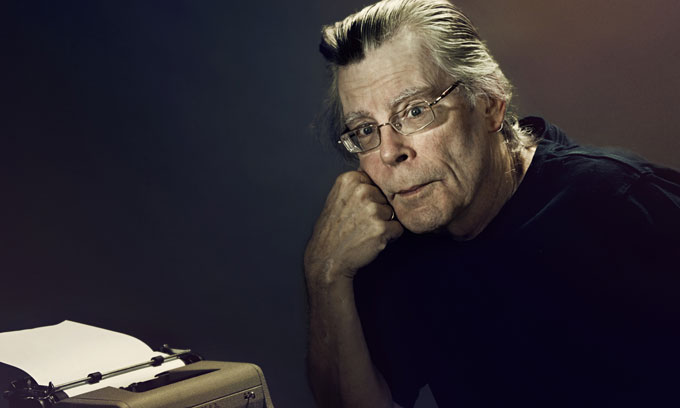

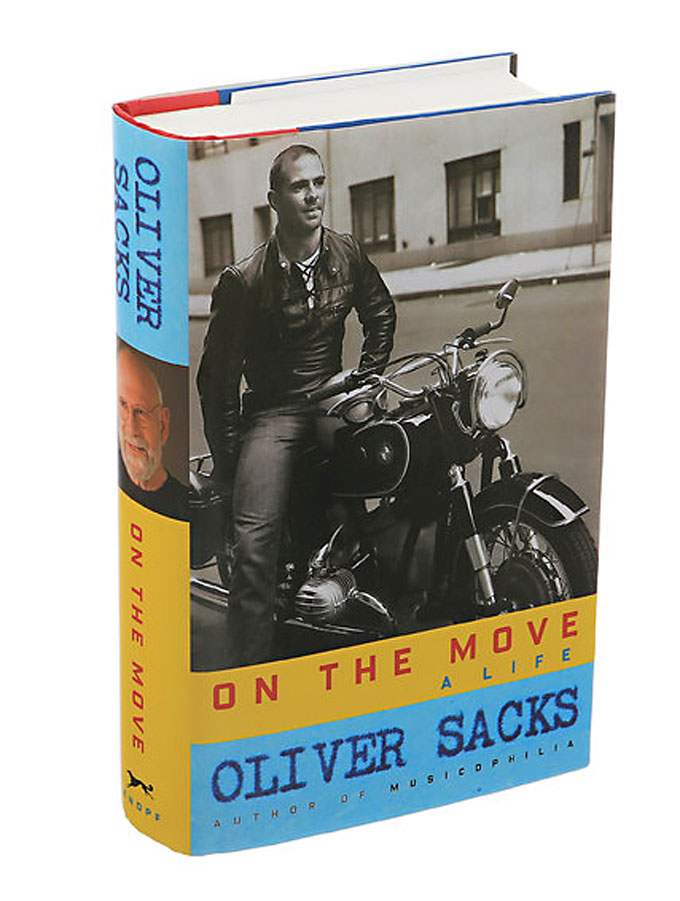

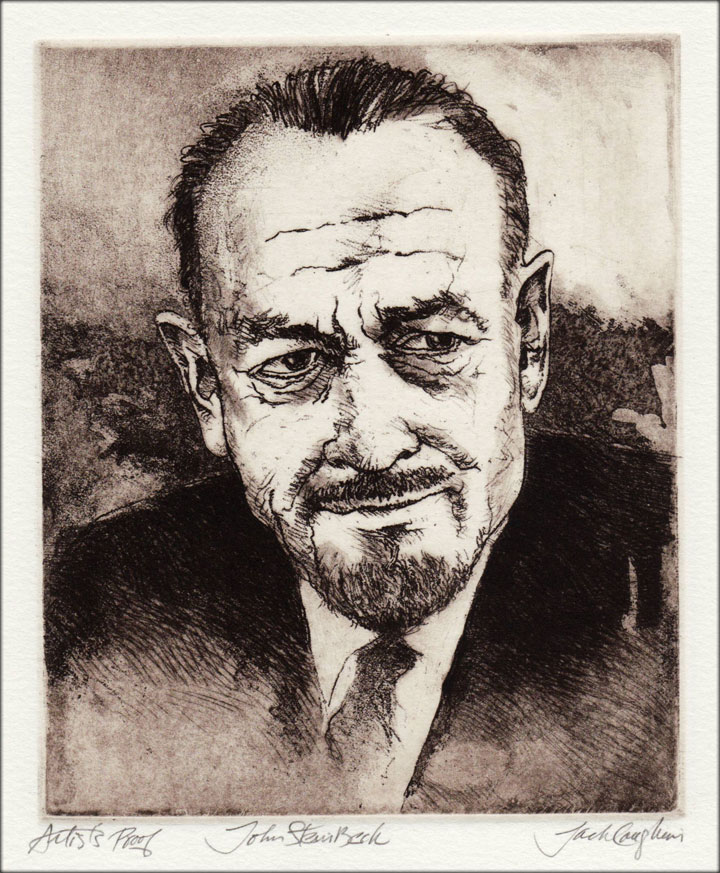

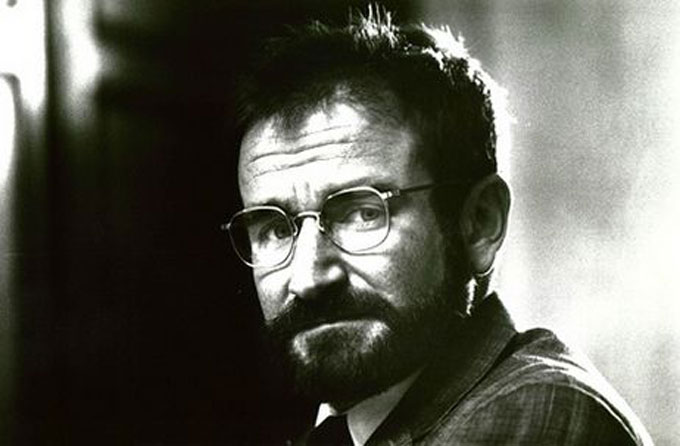

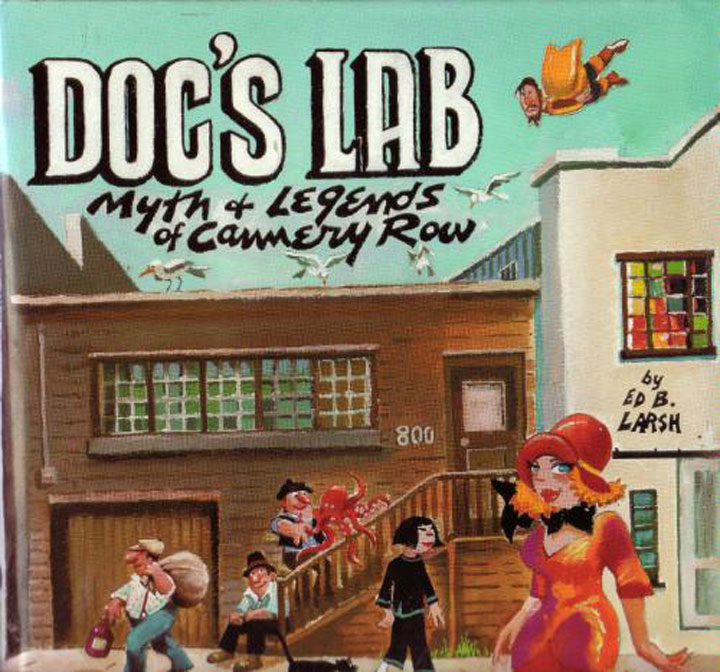

John Steinbeck wasn’t a fan of science fiction, but Stephen King, the reigning master of the form, is a fan of Steinbeck and his books, including Of Mice and Men. Steinbeck’s 1937 novella about George and Lennie plays a particularly important role in 11/22/63, King’s alternate history of America, published on November 8, 2011, five years to the day before Americans elect their 45th president. The TV adaptation of King’s novel downplayed Of Mice and Men but mentioned Steinbeck and starred James Franco, who played George on Broadway and Mac in the 2016 movie adaptation of In Dubious Battle. Like Steinbeck’s 1936 novel about the conflict between modern labor and capital, King’s horror-history of America after 1963 is powerful projection of a political divide that Steinbeck regretted but understood.

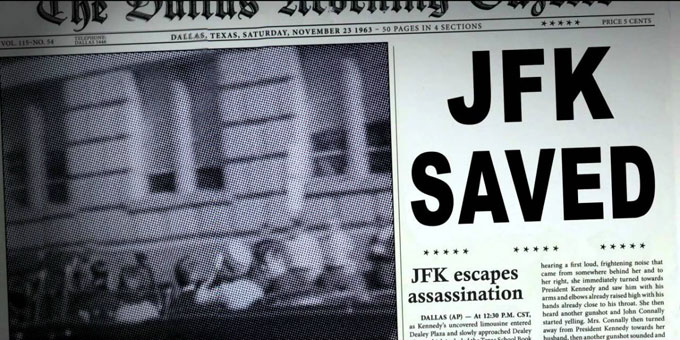

Of Mice and Men aside, the major alteration made in Hulu TV’s version of 11/22/63 is in the chain of events set in motion by Franco’s character, a high school English teacher from Maine who time-travels to Dallas to stop Lee Harvey Oswald from assassinating John Kennedy. While underscoring the danger of messing with the past, which like Texas resists interference, King’s story also deals with complexities of cause, effect, and unintended consequences around issues that preoccupy Americans from both political camps today—terrorism, race relations, and climate change, whether acknowledged (Hillary Clinton) or denied (Donald Trump).

In King’s alternate history of America, Kennedy lives to serve two terms but fails to enact civil rights legislation, end the escalating war in Southeast Asia, or prevent the election of George Wallace in 1968. President Wallace—a proto-Trump figure with a trigger-happy VP—firebombs Chicago, goes nuclear in Vietnam, and leaves an apocalyptic mess for a series of feckless, one-term successors that includes Humphrey, Reagan, and Clinton (Hillary, not Bill). Skipping this intervening narrative, the Hulu miniseries fast-forwards to a post-apocalyptic America populated by alien “Kennedy camps” and terrorist street gangs with dirty bombs—a version of alternate history certain to offend people who revere Kennedy while fulfilling the worst fears of those who revile Donald Trump.

Both groups include fans who will be disappointed in the diminished attention paid to John Steinbeck in the TV version of 11/22/63, where Of Mice and Men is basically limited to a favorite-book comment made by Franco’s character to the librarian who becomes his love interest. In the novel, long but not too long at 850 pages, Of Mice and Men provides dramatic depth, character development, and thematic amplification absent from the eight-part miniseries. Early in the book Franco’s character ponders the challenge of “exposing sixteen-year-olds to the wonders of Shakespeare, Steinbeck, and Shirley Jackson.” Later, while teaching in Texas, he directs Of Mice and Men in a high school production that provides a dimension of joy sadly missing from the miniseries: “At that moment I cared more about Of Mice and Men than I did about Lee Harvey Oswald . . . . I thought that Vince looked like Henry Fonda In The Grapes of Wrath.”

Of Mice and Men Helps 11/22/63 Connect with America

Stephen King, who co-wrote and produced the Hulu series, must share the blame—if that’s the word—for shortchanging John Steinbeck in the interest of narrative compression. The loss is regrettable, and in light of another change unnecessary as well. The first incidence of time travel in the novel takes place in the fictional town of Derry, Maine, a nightmare venue familiar to Stephen King fans from his other books. This episode is important, and it includes a character named Bill Turcotte, a slow-moving, middle-aged loser who threatens Franco’s character and gets left behind in Derry. In the TV version, the Derry action takes place in Kentucky and Turcotte—a wound-up ingénue—stays in the story as a sidekick, all the way to Dallas and the confrontation with Oswald. Unlike Derry and its scary clowns, Turcotte’s Kentucky feels tame. And the time devoted to his character, played by a 23-year-old English actor with a lousy Southern accent, would have been better invested in keeping Of Mice and Men, an essential piece of Americana, in the picture.

Stephen King, who co-wrote and produced the Hulu series, must share the blame—if that’s the word—for shortchanging John Steinbeck in the interest of narrative compression. The loss is regrettable, and in light of another change unnecessary as well. The first incidence of time travel in the novel takes place in the fictional town of Derry, Maine, a nightmare venue familiar to Stephen King fans from his other books. This episode is important, and it includes a character named Bill Turcotte, a slow-moving, middle-aged loser who threatens Franco’s character and gets left behind in Derry. In the TV version, the Derry action takes place in Kentucky and Turcotte—a wound-up ingénue—stays in the story as a sidekick, all the way to Dallas and the confrontation with Oswald. Unlike Derry and its scary clowns, Turcotte’s Kentucky feels tame. And the time devoted to his character, played by a 23-year-old English actor with a lousy Southern accent, would have been better invested in keeping Of Mice and Men, an essential piece of Americana, in the picture.

John Steinbeck, Donald Trump, and the King of Horror

But that’s a quibble. More important is the attention drawn to the phenomenon described years ago by the historian Richard Hofstadter as the paranoid style in American politics. During a recent interview with the book editor of The Washington Post, Stephen King confessed that “a Trump presidency scares me more than anything else.” Exercising and exorcising paranoia is what King does in his writing, of course, so whatever the outcome of this week’s election, it’s safe to assume that a scary-Trump novel will be making us scream soon. Maybe an alternate history of America since 2011? With John Steinbeck as a modern-day time traveler on a mission, like James Franco’s character in 11/22/63, to rewrite the record and save us from ourselves?

But that’s a quibble. More important is the attention drawn to the phenomenon described years ago by the historian Richard Hofstadter as the paranoid style in American politics. During a recent interview with the book editor of The Washington Post, Stephen King confessed that “a Trump presidency scares me more than anything else.” Exercising and exorcising paranoia is what King does in his writing, of course, so whatever the outcome of this week’s election, it’s safe to assume that a scary-Trump novel will be making us scream soon. Maybe an alternate history of America since 2011? With John Steinbeck as a modern-day time traveler on a mission, like James Franco’s character in 11/22/63, to rewrite the record and save us from ourselves?