I was recently asked to consider writing an essay about Steinbeck’s short novel The Pearl to be included in a text series for secondary and undergraduate English education. Frankly The Pearl wasn’t one of my favorite Steinbeck books, and I couldn’t imagine I would be able to come up with 20 pages on the short novel. But the more I reread it, the more the subject of the Song of the Pearl kept nudging my interest. I became curious about Steinbeck’s specifying a “song” as opposed to a musical note, chord, or phrase. I knew he was interested in classical music, and I believed his choice of the word “song” was important to the story. But the publisher’s formatting specifications were overwhelming and I couldn’t decide how to reduce the content to fit within the length requirements, so I decided to publish it elsewhere. I believe doing so is important to my personal mission to support the practical and scientific psychology of Carl Jung and William James as it was deftly applied by John Steinbeck in his fiction and non-fiction. The Song of the Pearl is about personal styles, levels of maturity, attitudes, and how such things influence individual perception, judgment, decision-making, problem-solving, and social bodies like the small indigenous coastal village of the central character in the novel.

Opposites Attract in Pursuit Of Travels with Charley

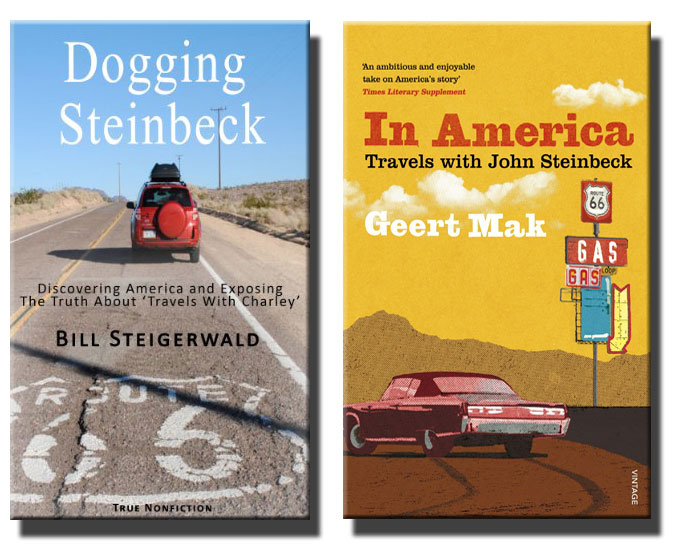

John Steinbeck delivered the speech of his life after taking the road trip described in Travels with Charley in Search of America, the last book he wrote before being awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature. Fifty-five years following Steinbeck’s acceptance speech in Stockholm, a pair of journalists who retraced Steinbeck’s route across America, and wrote separate books simultaneously, came together at a literary award event in Amsterdam attended by Queen Máxima of the Netherlands and broadcast on Dutch TV. Like their books, Bill Steigerwald and Geert Mak differ in background, language, and style. But they agree on issues, including Steinbeck’s accuracy in Travels with Charley, and their accord led to friendship. Like Steinbeck’s relationship with Bo Beskow, the Swedish artist who helped arrange Steinbeck’s speech in Stockholm, it flourished despite distance, and it led to Steigerwald’s speech in Amsterdam on November 27, when Mak was awarded the 2017 Prince Bernhard Cultural Prize for lifetime achievement as Queen Máxima looked on.

Writers Celebrate Meeting on John Steinbeck’s Trail

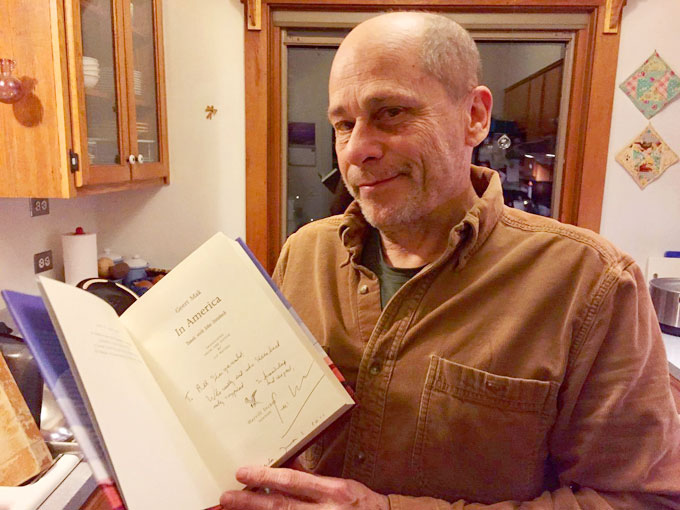

Bill Steigerwald, the investigative reporter from Pittsburgh who wrote Dogging Steinbeck “to expose the truth about Travels with Charley and celebrate Flyover America and its people six years before they elected Donald Trump,” is an American journalist with a rough edge and an independent streak. Geert Mak, the author of In America: Travels with John Steinbeck and the recipient of the award, is a Dutch journalist with European polish who writes popular history books that have drawn criticism from academics in Europe. When scholars in America downplayed or took offense at Steigerwald’s charges in Dogging Steinbeck, Mak emailed “to express my personal admiration for the job you did [and] to tell you that you became a kind of journalistic hero in my travel-story about Steinbeck.” He cited Steigerwald in the book he wrote to help readers in Europe, where John Steinbeck became a hero for writing The Moon Is Down, better understand contemporary America, where recent events have made the social criticism in Steinbeck’s American novels more relevant than ever. Mak inscribed a copy of his book to Steigerwald when it was translated from Dutch into English.

Colleague Writes Postscript to Speech in Amsterdam

The speech Bill Steigerwald gave about Geert Mak was short, like John Steinbeck’s address in Stockholm, and it left time to socialize, as Steinbeck did with Bo Beskow in 1962. The irony in this description of meeting Mak in America and paying tribute in Amsterdam sounds a bit like Steinbeck, who favored satire when he reported from Europe after World War II:

Geert Mak is my age, 70, and a masterful practitioner of drive-by journalism. In America sold a couple of hundred thousand copies in Holland, as most of his history books do. It was reviewed favorably by the Guardian newspaper, which liked both Mak’s fine writing and his left wing Euro-politics.

Mak, who calls himself a proud “half-socialist,” has visited America many times and lived for a while in Berkeley. In the fall of 2010, when he and his wife were a week into their 10,000-mile Charley road trip, in New Hampshire, he learned that I was traveling a day or two ahead of him.

Mak also soon learned I was posting a daily road blog to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and slowly revealing my charges that Steinbeck had fictionalized significant parts of Charley—which for half a century had been marketed, reviewed and taught as a nonfiction book.

Our relationship flourished online and two months ago I was suddenly asked to be a surprise guest at an elaborately produced and televised ceremony in Amsterdam honoring Mak for his impressive lifetime work. He is a household name in Holland and because he praised me in In America the people there were led to think I’m an important American journalist/author. As I wrote in an email to friends from Amsterdam after my speech, “I represented our great country with as little dignity as possible and I am proud to say that in my four-minute address—my world debut as a public speaker—I did not once bash America or use the T-word, though of course our dear leader was the embarrassing elephant in the room/country/continent.”

Mak’s prize was a crazy-looking necklace and 150,000 euros, but I was told by half a dozen people that the big hug he gave me during the event after my speech was the emotional high point of the show, which to a supposed hard boiled ex-newspaperman like me is a hilarious thought.

The American mode of mocking humor started with Mark Twain, the American drive-by journalist who invented “creative nonfiction,” and the idea of Innocents Abroad, when he wrote about his first trip to Europe. Thanks to Bill Steigerwald’s dogged pursuit, Travels with Charley has now been reassigned to the in-between category pioneered by Mark Twain 150 years ago. Thanks to Steigerwald’s long distance friendship with Geert Mak, Steinbeck was on stage again at another award event in Europe held to honor the achievements of a popular writer with mixed feelings about America.

John Steinbeck: A Literary Life, Literary Criticism from Palgrave Macmillan

John Steinbeck: A Literary Life, a book of literary criticism and biography by Linda Wagner-Martin, winner of the Hubbell Medal for Lifetime Service to American Literature, has been released by Palgrave Macmillan, the international academic and trade publishing company. The work is the latest in Palgrave Macmillan’s Literary Lives series. Wagner-Martin, a professor of English and comparative literature at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, contributed earlier biographies of Emily Dickinson, Ernest Hemingway, Sylvia Plath, and Toni Morrison to Literary Lives, described by Palgrave Macmillan as a “classic series, offering fascinating accounts of the literary careers of the most admired and influential English-language authors.” Chapters include “Steinbeck and the Short Story,” “Journalism v. Fiction,” and “The Ed Ricketts Narratives.” A hardback copy costs $109, the eBook version $85. Individual chapters can be purchased from Palgrave Macmillan in digital form for $29.95.

Steinbeck Now Publishes First Print Book and eBook

Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, a book of short stories about John Steinbeck’s life, family, and friends, has been published by SteinbeckNow.com in print and eBook format. Written by Steve Hauk, a playwright and fiction writer from Pacific Grove, California, the 16 short stories dramatize incidents in Steinbeck’s life—some real, some imagined—that take place over six decades, from the author’s childhood in Salinas, California to the years in New York, where his circle of family and friends included Burgess Meredith, Joan Crawford, and Elaine Steinbeck, the widow with whom Hauk had a memorable conversation 30 years after John Steinbeck’s death. Illustrated by Caroline Kline, an artist on California’s Monterey Peninsula, Steinbeck: The Untold Stories represents a milestone in the mission of SteinbeckNow.com to foster fresh thinking and new art inspired by Steinbeck’s life and work. If you are in a position to review or write about the book for publication in print or online, email williamray@steinbecknow.com for a review copy. Please identify the print publication or website, the date when your print piece or post will appear, and whether you prefer print or eBook format. Steinbeck: The Untold Stories is available through Amazon.com, in Monterey-area bookstores, and at Hauk Fine Arts in Pacific Grove and the National Steinbeck Center and Steinbeck House in Salinas, California.

Steve Hauk will autograph copies from 11:30 a.m. till 12:15 p.m. on Saturday, November 25, 2017, at the Pilgrim’s Way Community Bookstore on Dolores Street between 5th and 6th Streets in Carmel, California.

Critical Insights into John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men

Critical Insights: Of Mice and Men, a collection of literary criticism devoted to John Steinbeck’s Great Depression novella, is now available at Amazon.com. Edited by Barbara A. Heavilin with an introduction by Robert DeMott, it includes essays by Nick Taylor, Brian Railsback, Kathleen Hicks, Laura Smith, Luchen Li, Mimi Gladstein, Tom Barden, Danika Čerče, Cecilia Donahue, and Richard E. Hart, along with a Steinbeck chronology and a bibliography of scholarly writing about Of Mice and Men, a work that re-entered political discourse when the so-called Lenny rule was cited by defenders of capital punishment in a Texas case that recently made its way to the United State Supreme Court. Barbara Heavilin, a professor emeritus at Taylor University and the executive editor of Steinbeck Review, said this about the book’s relevance and the significance of literary criticism devoted to its understanding and appreciation: “I particularly wanted Critical Insights: Of Mice and Men to provide fresh, new insights on this novella, with articles provided by reputable Steinbeck scholars writing on their specialties. Mimi Gladstein, for example, writes on feminism, and Robert DeMott provides an insightful overview, among other well-known experts in the field of Steinbeck studies.”

Steinbeck Review Features Literary Criticism, History, Bibliography, and News

Penn State University Press recently released the first of two issues of the academic journal Steinbeck Review to be published in 2017. Along with news and reviews, it features essays in literary criticism by Gavin Jones, professor of English at Stanford University; Barbara A. Heavilin, editor of Critical Insights: Of Mice and Men; Harold Augenbraum, former executive director of the National Book Foundation, presenter of the National Book Award; Cecilia Donahue, a retired university teacher and a contributor to the Literary Encyclopedia database; Netta Bar Yosef-Paz, a literature teacher at Kibbutzim College, Israel’s largest college; Chaker Mohamed Ben Ali, a doctoral student at the University of Skikda, Algeria; and Hachemi Aboubou, assistant dean at Batna Benboulaid University, also in Algeria. The issue includes reviews of Citizen Steinbeck: Giving Voice to the People, a book of literary criticism by Robert McPartand, and Monterey Bay, a novel, as well bibliographies of recent books, articles, theses, and dissertations on John Steinbeck’s life and work. An annual subscription costs $35 and includes both print and digital editions of Steinbeck Review.

How John Steinbeck’s In Dubious Battle Helps Us Navigate Social Discord

Rarely since the Great Depression has our country been as polarized and angry as it is today. On television, in newspapers, on social media, around the office water cooler, in line at the supermarket, even at the family dinner table, there is constant clashing and creating of divisions. Warring political parties, “special interest” groups competing for social change, and an endless series of labels–liberal and conservative, Republican and Democrat, libertarian or evangelical–work to separate us from one another. More and more, Americans are being asked to take sides in this battle of interests and ideas, magnified by social media and the 24-hour news cycle. Inserting sanity into the crock pot of conflicting ideologies can be challenging. Reading John Steinbeck, one of America’s greatest writers and keenest observers, offers a way out of the insanity.

Rarely since the Great Depression has our country been as polarized and angry as it is today.

Eighty years before it was made into a mixed-review movie by the mercurial actor-director James Franco, Steinbeck’s Great Depression labor novel In Dubious Battle explored the complex relationship between the individual and the group, sometimes referred to in Steinbeck’s writing by its more malevolent moniker, “the mob.” Using a strike-torn California apple orchard as his backdrop, Steinbeck deep-dives into phalanx or “group-man” theory, grittily exposing the causes and consequences of a volatile, violent labor struggle involving pickers and organizers, growers and landowners, vigilantes and victims, and outside agitators who are never called “communists” but clearly are.

Steinbeck’s Great Depression labor novel explored the complex relationship between the individual and the group, sometimes referred to in Steinbeck’s writing as ‘the mob.’

In his introduction to the 1995 Penguin Books edition of Steinbeck’s Log from the Sea of Cortez, Richard Astro, Provost Emeritus and Distinguished Professor of English at Drexel University, writes that Steinbeck’s ideas on “group-man” thinking were influenced by the writing of the California biologist William Emerson Ritter (1856-1944). According to Astro, Ritter thought that “in all parts of nature and in nature itself as one gigantic whole, wholes are so related to their parts that not only does the existence of the whole depend upon their orderly co-operation and interdependence of the parts, but the whole exercises a measure of determinative control over its parts.” Ritter also believed that “man is capable of understanding the organismal unity of life and, as a result, can know himself more fully. This, says Ritter, is ‘man’s supreme glory’ – not only ‘that he can know the world, but he can know himself as a knower of the world.’”

Steinbeck’s ideas on ‘group-man’ thinking were influenced by the writing of the California biologist William Emerson Ritter.

Steinbeck illuminates “group-man” thinking in much of his Great Depression fiction, especially the idea that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. But this central tenet of Ritter’s theory is voiced most clearly by the character Doc Burton in the 1936 novel whose title—In Dubious Battle—Steinbeck took from John Milton’s 17th century poem Paradise Lost. Explaining his participation and fascination with the apple pickers’ strike, Burton says, “I want to watch these group-men, for they seem to be a new individual, not at all like single men. A man in a group isn’t himself at all, he’s a cell in an organism that isn’t like him anymore than the cells in your body are like you. I want to watch the group, and see what it’s like. People have said, ‘mobs are crazy, you can’t tell what they’ll do.’ Why don’t people look at mobs as men, but as mobs? A mob nearly always seems to act reasonably, for a mob.”

The central tenet of Ritter’s theory is voiced most clearly by the character Doc Burton in the 1936 novel whose title Steinbeck took from Milton.

As marches, movements, protests, and counter-protests increase in volume and virulence, Steinbeck’s insights into the behavior of “group-man,” through the words and actions of Doc Burton, can be viewed as prescient indeed, particularly by Americans who know their history. Midway through the book, in a passage worthy of one of history’s greatest thinkers–a passage I submit provides an outlook on life that, if adopted, could alleviate much of the rancor in America–Burton says this to the communist agent sent from San Francisco to organize the orchard strike: “That’s why I don’t like to talk very often. Listen to me, Mac. My senses aren’t above reproach, but they’re all I have. I want to see the whole picture–as nearly as I can. I don’t want to put on the blinders of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, and limit my vision. If I use the term ‘good’ on a thing I’d lose my license to inspect it, because there might be bad in it. Don’t you see? I want to be able to look at the whole thing.”

Steinbeck’s insights into the behavior of ‘group-man’ can be viewed as prescient, particularly by Americans who know their history.

In “John Steinbeck, American Writer,” Susan Shillinglaw, Professor of English at San Jose State University, notes that “in most of his fiction Steinbeck includes a ‘Doc’ figure, a wise observer of life who epitomizes [Steinbeck’s] idealized stance of the non-teleological thinker.” Non-teleological thinking, she explains, is “‘is’ thinking” marked by “detached observation” and a “remarkable quality for acceptance.” Reinforcing Steinbeck’s obeisance to this philosophy–an open and tolerant approach to ideas and to the people who believe in them that is desperately needed today–Shillinglaw highlights a journal entry made by Steinbeck in 1938: “[T]here is a base theme. Try to understand men, if you understand each other you will be kind to each other. Knowing a man well never leads to hate and nearly always leads to love.”

‘[T]here is a base theme. Try to understand men, if you understand each other you will be kind to each other. Knowing a man well never leads to hate and nearly always leads to love.’

Eschewing the American impulse to classify, pigeonhole, prejudge, discount, and disparage opposing ideas and those who hold them, Doc Burton prescribes detached observation and personal experience as an alternative to blind theory and blind hatred. Looking back on the unbiased Doc-like worldview favored by his father, Thom Steinbeck told an interviewer in 2012 that Steinbeck always ended his beautifully written letters to his son with this bit of advice: “Good luck. Find out on your own.” Finding out on our own is a good way, perhaps the only way, to survive the dubious battle of ideologies raging within and around us in 2017.

Why John Steinbeck Matters In Donald Trump’s America

“Steinbeckian” hasn’t achieved the currency of “Orwellian” as a term of obloquy for despotic language or behavior, but a cheerfully statistical item in The Atlantic reports that sales of John Steinbeck’s novel The Winter of Our Discontent—like George Orwell’s 1984—have spiked under the authoritarian shadow of Donald Trump, a bully and a blowhard of Steinbeckian, if not Orwellian, stature. While less apocalyptic than George Orwell’s nightmare dystopia, the world of The Winter of Our Discontent seethes with rancid resentment, greed, and xenophobia of the noisy, feculent variety increasingly associated with Donald Trump’s resurgent, alt-right America. The Atlantic article explains: “If the links between the events of the recent year and Steinbeck’s last book don’t seem entirely clear, The Atlantic’s review, published in 1961, is illuminating: ‘What is genuine, familiar, and identifiable [about the book] is the way Americans beat the game: the land-taking before the airport is built, the quick bucks, the plagiarism, the abuse of trust, the near theft, which, if it succeeds, can be glossed over—these are the guilts with which Ethan will have to live in his coming prosperity, and one wonders how happily.’” Steinbeckian is a good term for a bad leader who beat the American game, achieving personal prosperity and political power through means that can only be described as Orwellian.

Of Mice and Men In the News

The January 21 episode of Saturday Night Live gave a shout-out to John Steinbeck during the weekly fake-news feature “Weekend Update,” further substantiating Steinbeck’s pop-culture standing and sending Of Mice and Men students back to the book to find out what George really says to Lennie at the end. Two-and-a-half minutes into the skit, faux news-anchor Colin Jost compares Barack Obama’s parting comment about Donald Trump (“it’s going to be ok”) with the assurance George gives Lennie before he shoots Lennie in the head. It’s a safe bet that the latest Of Mice and Men moment on TV will be seen by millions of schoolkids, and by hipper teachers too.

W.H. Auden and His Kind: Christopher Isherwood on The Grapes of Wrath in 1939

Shortly after emigrating to America in 1939 with the poet W. H. Auden, Christopher Isherwood, the British author of Berlin Stories, wrote a review of The Grapes of Wrath for Kenyon Review, the new American literary magazine that—like John Steinbeck—quickly gained prestige and influence with readers and critics in the United States. Intimate friends since school days in England, Isherwood and Auden arrived in New York in January. Isherwood moved on to California, and in July confided this to his diary: “I forced myself to write—a review of The Grapes of Wrath and a short story called “I Am Waiting”—but there was no satisfaction in it.” Despite his mood, Isherwood’s review of The Grapes of Wrath was upbeat and positive; like the diaries, novels, and plays that he produced over five decades in America, his insights (and criticism) seem as fresh today as they were in 1939. What made Christopher Isherwood, an adoptive American, so receptive to John Steinbeck’s all-American novel when it was published? Temperamentally and socially the two men were opposites. Steinbeck preferred privacy and solitude to self-confession and self-promotion, the distinguishing features of Isherwood’s career as the main character in his books. Steinbeck’s people were middle-class, immigrant, and self-made; Isherwood came from landed gentry with deep roots in English history. But both men believed in the power of sympathy and synchronicity, and coincidence can be as important as difference in life, as in literature.

John Steinbeck, Christopher Isherwood, and Synchronicity

Both writers were born in the decade prior to World War I, when America—like England—was outgrowing Victorianism. Both were christened (and later confirmed) into the Anglican Church, an experience that effected their prose style, if not their souls. Each was an elder or only son in a family dominated by an ambitious mother: Isherwood’s father was a British infantry officer who was killed at Ypres in 1915, leaving behind a wife and two sons, an older brother who inherited the Isherwood fortune, and three younger siblings with Steinbeckian names—John, Esther, and Mary. From childhood, John Steinbeck and Christopher Isherwood were imaginative storytellers with a drive to write that drove them to drop out of college to follow their muse. By 1940 both had achieved success in their calling and hobnobbing with film-world celebrities and hangers-on in Hollywood. Despite holding opposite views about the value of autobiography, both worked well in various forms, writing novels, play-novelettes, travel books, and war correspondence that attracted a following. Each loved the warmth of the sun and the sound of the sea—unlike W.H. Auden, who stayed behind in New York in 1939 when Isherwood left for Los Angeles, where Isherwood remained until he died in 1986. (He became an American citizen in 1946.) Oddly, though Hollywood was a village and they had mutual friends in the business, neither Isherwood’s dairies not Steinbeck’s biographers suggest that they ever met.

W.H. Auden and His Kind Weren’t John Steinbeck’s

Nature and nurture conspired to keep them apart. Like other members of W.H. Auden’s circle, Isherwood was openly gay from an early age. Steinbeck grew up in small-town Salinas, where deviance was closeted; the Isherwoods were cosmopolitan provincials with property in London (Isherwood’s Uncle Henry was homosexual, and a jurist ancestor signed King Charles’s death warrant). Unlike Steinbeck, who struggled at the start and stayed in America until established, Isherwood inherited position, connections, and cash that helped pave his way, traveling extensively in Europe before settling in America. His exploration of Berlin’s pre-Nazi gay underground provided material for the 1930s Berlin fiction later adapted for stage and screen as Cabaret. His early novels—All the Conspirators (1928), The Memorial (1932), Mr. Norris Changes Trains (1935)—sold better than Steinbeck’s books—Cup of Gold, The Pastures of Heaven, To a God Unknown—published in the same period. Above all, his relationships with other writers differed dramatically from those of Steinbeck. Isherwood was a born extrovert who wrote poetry and plays with W.H. Auden and nourished friendships with other famous authors, including Aldous Huxley and Thomas Mann. Steinbeck took a disliking to Alfred Hitchcock, the quintessentially English snob who directed the war movie (Lifeboat) scripted by Steinbeck. Isherwood’s collaboration with the Austrian director Berthold Viertel was so gratifying that he wrote a novel (Prater Violet) about their friendship.

A Neglected Grapes of Wrath Review, Still Relevant Today

Christopher Isherwood had a reputation as a ready reviewer when he arrived in America with W.H. Auden, so the Grapes of Wrath assignment made sense. Although the piece he produced for The Kenyon Review is mentioned in John Steinbeck: The Contemporary Reviews (Cambridge University Press, 1996), that helpful anthology omits the full text, which seems a shame. Fortunately, it can be found in Exhumations (Simon and Schuster, 1966), a collection of Isherwood’s stories, articles, and verse that also includes reviews of authors (Stevenson, Wells, T.E. Lawrence) of interest to Steinbeck and Isherwood, two writers with more in common than their differences suggest. Here are four samples, still relevant, from the 1939 review of John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath:

(1) On the Promise of Steinbeck’s California

“Meanwhile, the sharecroppers have to leave the Dust Bowl. They enter another great American cycle—the cycle of migration towards the West. They become actors in the classic tragedy of California. For Eldorado is tragic, like Palestine, like every other promised land.”

(2) On Participating in Steinbeck’s Story

“It is a mark of the greatest poets, novelists and dramatists that they all demand a high degree of co-operation from their audience. The form may be simple, and the language as plain as daylight, but the inner meaning, the latent content of a masterpiece, will not be perceived without a certain imaginative and emotional effort. . . . The novelist of genius, by presenting the particular instance, indicates the general truth [but] the final verdict, the ultimate synthesis, must be left to the reader; and each reader will modify it according to his needs. The aggregate of all these individual syntheses is the measure of the impact of a work of art upon the world.”

(3) On Didacticism in Fiction

“Mr. Steinbeck, in his eagerness for the cause of the sharecroppers and his indignation against the wrongs they suffer, has been guilty, throughout this book, of such personal, schoolmasterish intrusions upon the reader. Too often we feel him at our elbow, explaining, interpreting, interfering with our independent impressions. And there are moments at which Ma Joad and Casy—otherwise such substantial figures—seem to fade into mere mouthpieces, as the author’s voice comes through, like the other voice on the radio.”

(4) On Art vs. Life in Novels

“If you claim that your characters’ misfortunes are due to the existing system, the reader may retort that they are actually brought about by the author himself. Legally speaking, it was Mr. Steinbeck who murdered Casy and killed Grampa and Granma Joad. In other words, fiction is fiction. Its truths are parallel to, but not identical with, the truths of the real world.”