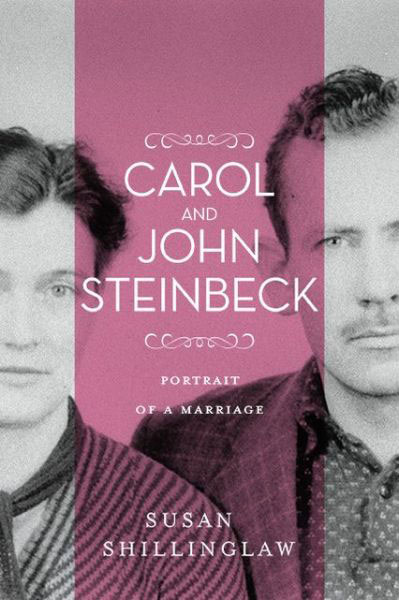

Nobody knows more or writes better about the life of Steinbeck than Susan Shillinglaw, professor of English at San Jose State University, former director of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies, and scholar-in-residence at the National Steinbeck Center. Her superb scholarship and elegant style are equally evident in Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage, the biography of Steinbeck’s marriage to Carol Henning, a Jazz Age rebel with a Great Depression conscience. As Shillinglaw observes, John and Carol were no Scott and Zelda. But their dramatic story book reads like a novel—unfortunately, one with a similarly unhappy ending.

Nobody knows more or writes better about the life of Steinbeck than Susan Shillinglaw, professor of English at San Jose State University, former director of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies, and scholar-in-residence at the National Steinbeck Center. Her superb scholarship and elegant style are equally evident in Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage, the biography of Steinbeck’s marriage to Carol Henning, a Jazz Age rebel with a Great Depression conscience. As Shillinglaw observes, John and Carol were no Scott and Zelda. But their dramatic story book reads like a novel—unfortunately, one with a similarly unhappy ending.

From Jazz Age Joy to Great Depression Decline

Meticulously researched over a period of 20 years, Shillinglaw’s life of Steinbeck and his first wife, from Jazz Age joy through Great Depression decline, describes a companionable marriage of equals and opposites, revealing intimate details of a relationship that began in 1928, at the cusp of Steinbeck’s career, and dissolved following the success of The Grapes of Wrath. Using Steinbeck’s phalanx metaphor, she demonstrates how such a relationship becomes a kind of third person, with characteristics, dynamics, and patterns of development and decay distinct from both partners and ultimately beyond their control. Her subject is the life and death of a relationship, but her protagonist is clearly Carol, a shining figure in the life of Steinbeck who has remained in her husband’s shadow until now.

Years after his divorce from Carol, Steinbeck advised another writer that “your work is your only weapon.” As Shillinglaw shows, John and Carol’s collaboration in Steinbeck’s signature work of the 1930s—always his work, rarely hers—was their mutual weapon against poverty and insecurity until fortune and fame—his, not hers—intervened. The title of Steinbeck’s anthem of the Great Depression, The Grapes of Wrath, was her idea. The progressive politics of the protest novels that preceded it—In Dubious Battle and Of Mice and Men—were hers before they were his. She became his muse and motivator, typist and editor, connector and companion. But the 12-year experience drained and disoriented her, leaving her ill-equipped to cope with wealth, notoriety, and competition from the woman who became Steinbeck’s second wife in 1943.

A Life of Steinbeck Story Told by the Perfect Narrator

Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage is a book only Susan Shillinglaw could have written. The life of Steinbeck has been chronicled by men—notably Jackson Benson, the author of The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer—with an emotional detachment from their distant, difficult subject. Unlike her husband, Carol demanded attention, engagement, and shared context, qualities that Shillinglaw brings to the story of her life before, with, and after Steinbeck. A resident of Pacific Grove and Los Gatos—towns where the Steinbecks lived for most of their marriage—Shillinglaw teaches in the city where Carol was born, raised, and rooted. Married to a biologist at the Hopkins Marine Station, the Monterey outpost of Stanford University where Steinbeck took summer courses, Shillinglaw collaborates with her husband in a imaginative summer program for high school teachers passionate about Steinbeck. The author of an upcoming book on The Grapes of Wrath, she shares context with the woman who—in Steinbeck’s words—“willed it.”

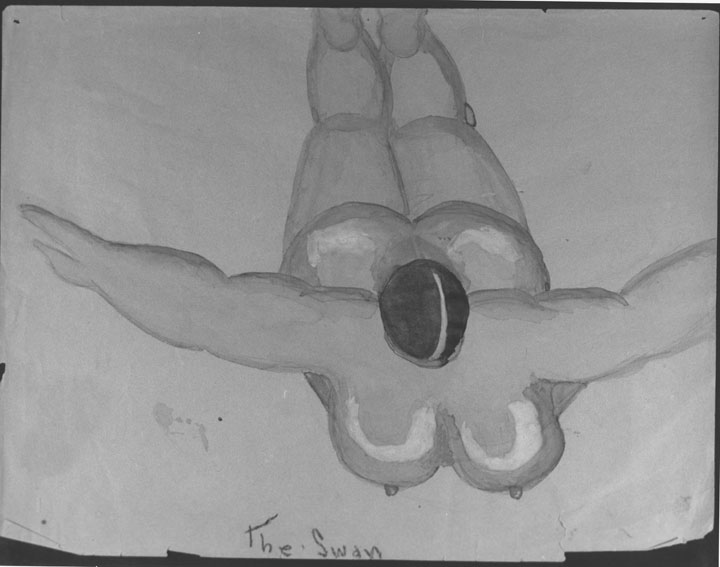

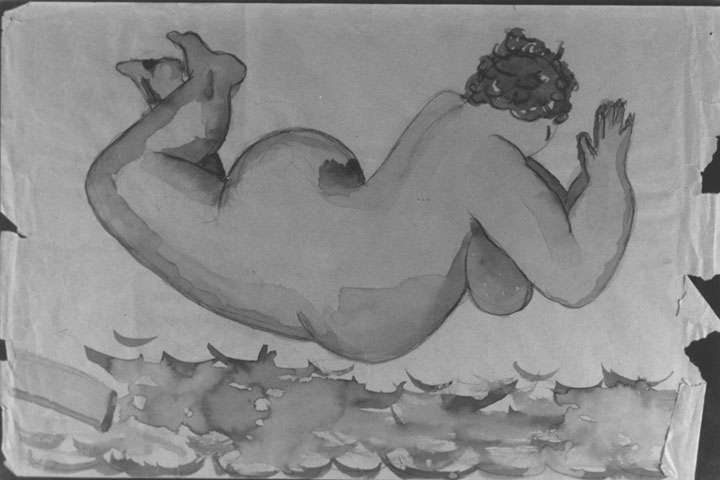

To the credit of Shillinglaw’s publisher, her life of Steinbeck and Carol Henning’s marriage is affordable, attractive, and accessible to non-academics. Unfortunately, small inconsistencies were overlooked, marring an otherwise masterful achievement. Several sentences introduce names left unexplained until later, end without punctuation, and place closing quotation marks on the wrong side of the period. End notes are copious and unobtrusive, but the name of Dick Hayman is printed twice in a sentence thanking sources, and the index seems incomplete. (Mary Dole, the pineapple-heiress acquaintance of Carol’s estranged sister Idell, is included, but Bennett Cerf—the publisher who arranged the Steinbecks’ introduction to the poet Robinson Jeffers—is omitted.) Jazz Age children of musical families, Carol and John both loved music, a pursuit—like Carol’s drawing and sculpting—documented in satisfying detail. Yet Carol’s talented mother is described as attending music school in San Jose to improve her “piano techniques,” not technique, and Gregorian chant (a collective noun, like opera) is referred to as “Gregorian chants.”

To the credit of Shillinglaw’s publisher, her life of Steinbeck and Carol Henning’s marriage is affordable, attractive, and accessible to non-academics. Unfortunately, small inconsistencies were overlooked, marring an otherwise masterful achievement. Several sentences introduce names left unexplained until later, end without punctuation, and place closing quotation marks on the wrong side of the period. End notes are copious and unobtrusive, but the name of Dick Hayman is printed twice in a sentence thanking sources, and the index seems incomplete. (Mary Dole, the pineapple-heiress acquaintance of Carol’s estranged sister Idell, is included, but Bennett Cerf—the publisher who arranged the Steinbecks’ introduction to the poet Robinson Jeffers—is omitted.) Jazz Age children of musical families, Carol and John both loved music, a pursuit—like Carol’s drawing and sculpting—documented in satisfying detail. Yet Carol’s talented mother is described as attending music school in San Jose to improve her “piano techniques,” not technique, and Gregorian chant (a collective noun, like opera) is referred to as “Gregorian chants.”

Minor errors in major works can be corrected in subsequent editions. I predict that Susan Shillinglaw’s life of Steinbeck and Carol Henning’s together from Jazz Age joy to Great Depression decline—a dramatic story told by the perfect narrator—will have many.

Minor errors in major works can be corrected in subsequent editions. I predict that Susan Shillinglaw’s life of Steinbeck and Carol Henning’s together from Jazz Age joy to Great Depression decline—a dramatic story told by the perfect narrator—will have many.

Drawings by Carol Henning Steinbeck courtesy of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies, San Jose State University.