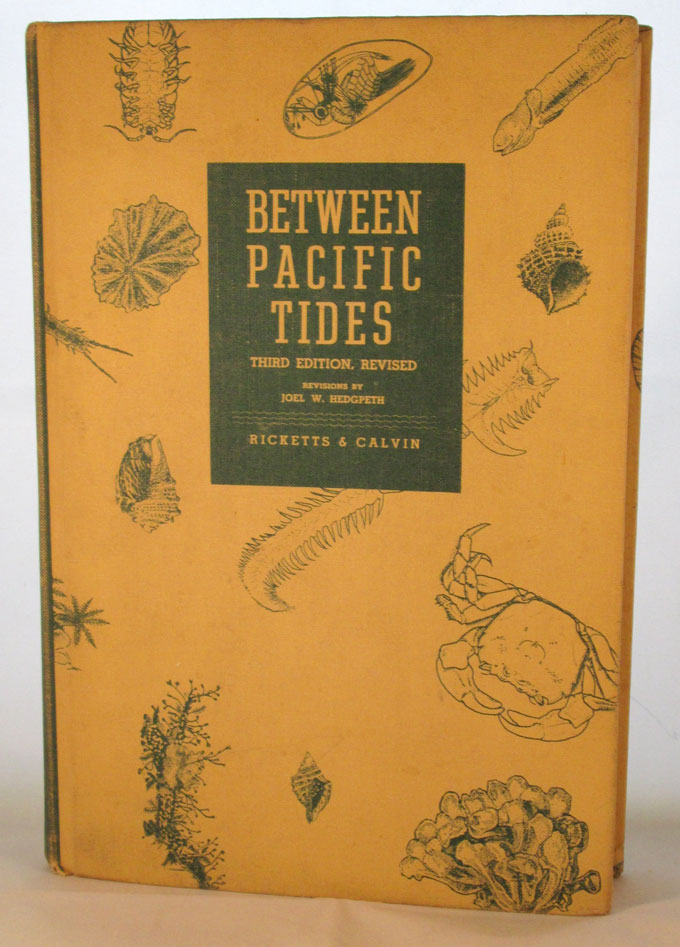

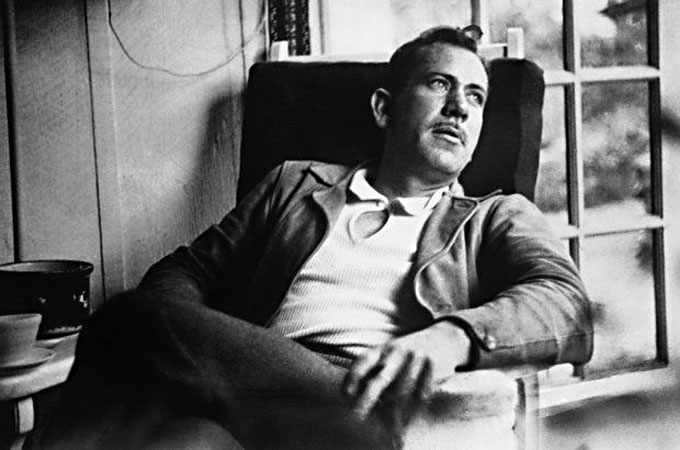

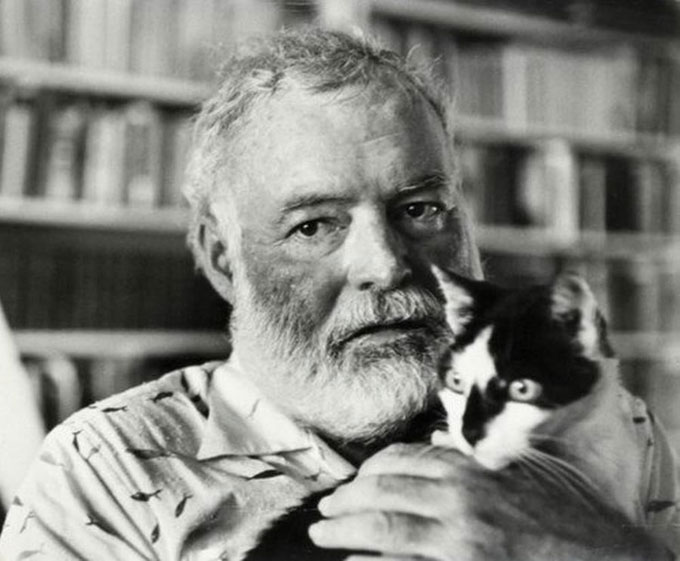

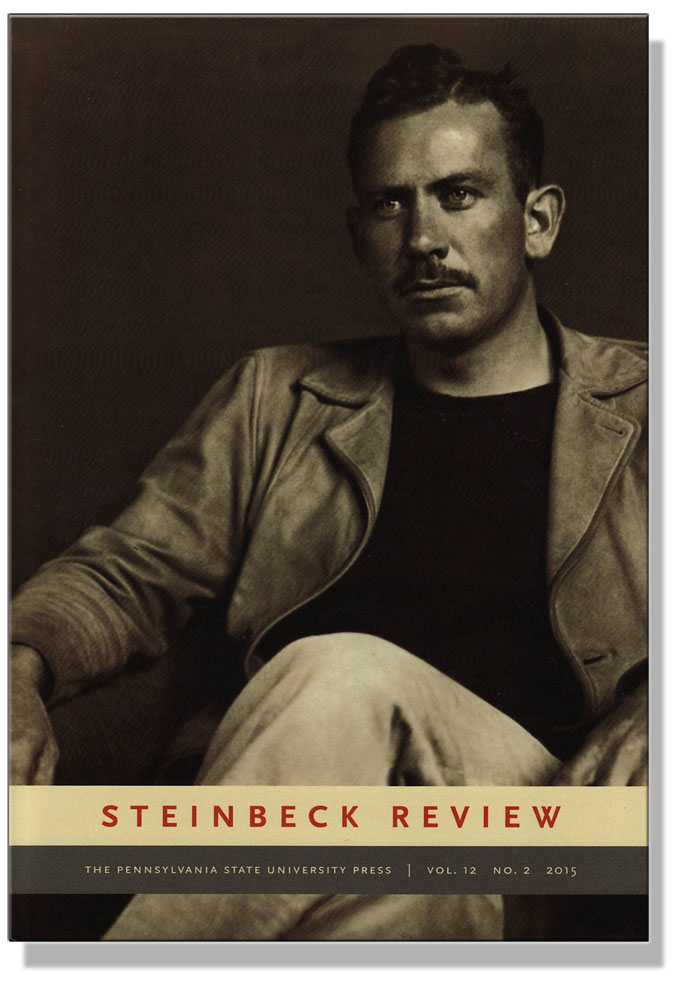

Sea of Cortez, the record of John Steinbeck’s 1940 exploration of Baja California with Edward F. Ricketts, has become a familiar source for fans of both men, and for students of marine biology. Less well known is the story behind Between Pacific Tides, the pioneering marine biology text by Ricketts and Jack Calvin, another Steinbeck friend, published by Stanford University in 1939, the year The Grapes of Wrath appeared. My research on the history of the Hopkins Seaside Laboratory and Hopkins Marine Station, and the Chautauqua nature study movement in Pacific Grove, touches on a formative phase in the life of Steinbeck, who took a summer biology course while a Stanford University student that helped set the stage for his introduction to Ricketts when Steinbeck, who left college in 1925, moved to Pacific Grove.

My research addresses intriguing questions about Ed Ricketts and his book raised by biographers, critics, and historians. The proposal for Between Pacific Tides was presented to Stanford University Press in 1930, the year Ricketts and Steinbeck met. Was the book’s publication slowed by the Director of Hopkins Marine Station Walter K. Fisher’s critical review of the manuscript? Did Stanford University Press dislike the ecological approach taken by Ricketts, whose holistic science and philosophy profoundly influenced Steinbeck’s thought and writing? Was Ricketts completely isolated from the scientific community of Hopkins Marine Station, as has often been suggested? The discovery of numerous letters between Ricketts, Stanford University Press, and invertebrate specialists around the world provides answers to these and other questions, chapter by chapter, in the book that I am writing about the delayed publication of Between Pacific Tides.

My research addresses intriguing questions about Ed Ricketts and his book raised by biographers, critics, and historians. The proposal for Between Pacific Tides was presented to Stanford University Press in 1930, the year Ricketts and Steinbeck met. Was the book’s publication slowed by the Director of Hopkins Marine Station Walter K. Fisher’s critical review of the manuscript? Did Stanford University Press dislike the ecological approach taken by Ricketts, whose holistic science and philosophy profoundly influenced Steinbeck’s thought and writing? Was Ricketts completely isolated from the scientific community of Hopkins Marine Station, as has often been suggested? The discovery of numerous letters between Ricketts, Stanford University Press, and invertebrate specialists around the world provides answers to these and other questions, chapter by chapter, in the book that I am writing about the delayed publication of Between Pacific Tides.