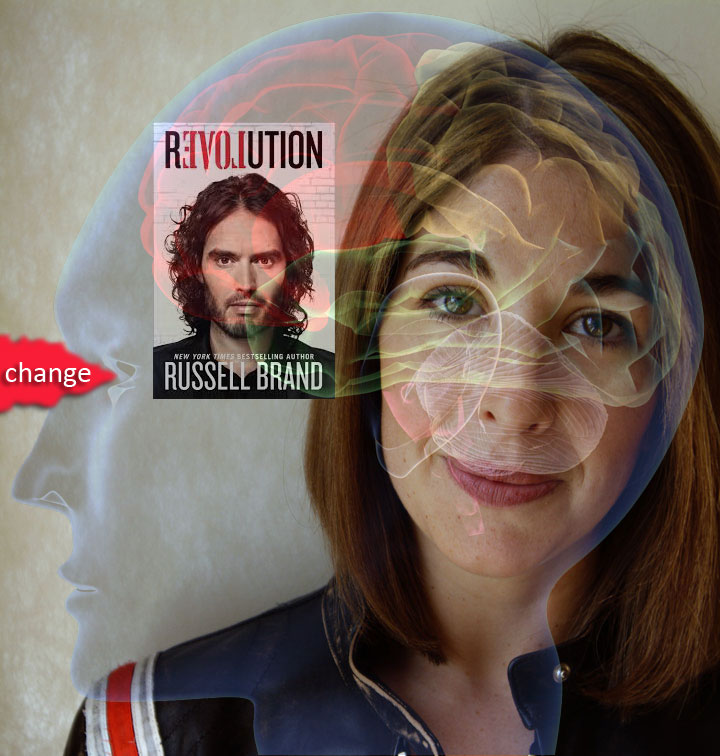

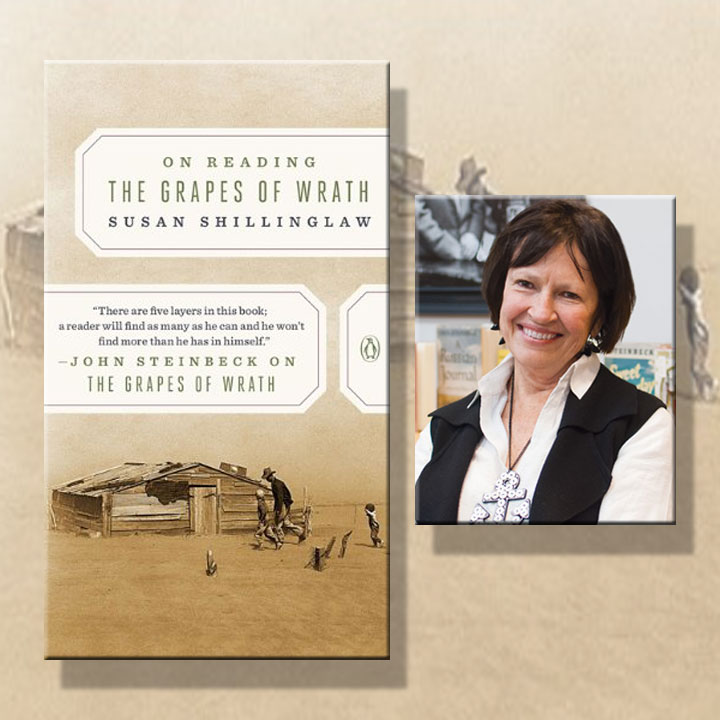

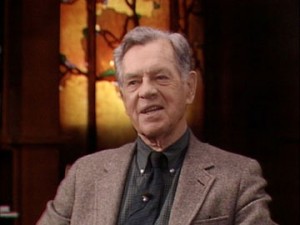

Though he’d probably be puzzled by the media contemporary counter-cultural critics like Russell Brand and Naomi Klein employ to communicate the human cost of mounting income inequality, predatory capitalism, and pending climate crisis—YouTube, podcasts, personal websites—John Steinbeck would likely agree with their call for a revolution in how we think and organize ourselves as a survival-species. I encourage you to read Russell’s Brand’s Revolution and Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything, both published in 2014, if like me, The Grapes of Wrath captivated your imagination and outraged your sense of justice.

Though he’d probably be puzzled by the media employed, John Steinbeck would likely agree with the call for a revolution in how we think and organize ourselves as a survival-species.

Not long after meeting Joseph Campbell—quoted by Brand and Klein in their writing about human belief and behavior—Steinbeck encountered first hand the evidence of destructive income inequality and environmental degradation in the Midwestern Dust Bowl and California labor camps of the Great Depression. The Grapes of Wrath was the result of John Steinbeck’s personal epiphany. Both the struggle and the enlightenment he dramatized continue in our time. Russell Brand and Naomi Klein project Steinbeck’s local vision on a global screen, exposing the noxious roots of global income inequality, climate change, and predatory capitalism—problems that are worse today than when John Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath.

‘The Grapes of Wrath’ was the result of John Steinbeck’s personal epiphany. Both the struggle and the enlightenment he dramatized continue in our time.

As I read Russell Brand and Naomi Klein, it occurred to me that they were really channeling John Steinbeck, even when quoting Joseph Campbell or James Lovelock, the British biologist whose 1960s Gaia theory (Earth as a single organism comprised of interconnected systems) reflects advanced thinking about ecology expressed by John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts in Sea of Cortez. For that matter, Tortilla Flat presages the small-group collectivism espoused by Russell Brand in Revolution, and Travels with Charley suggests the same connections between consumerism, conflict, and unhappiness drawn by Brand and Naomi Klein in their books. Events have caught up with John Steinbeck’s prophecy; as I write, his beloved city of Paris remains on security alert following the Charlie Hebdo massacre, and Agence France-Presse reports that the richest one percent of the world’s population will own half of the world’s wealth by next year. Like John Steinbeck, Russell Brand and Naomi Klein wish to advise us of disaster ahead.

As I read Russell Brand and Naomi Klein, it occurred to me that they were really channeling John Steinbeck, even when quoting Joseph Campbell or James Lovelock, the British biologist whose 1960s Gaia theory (Earth as a single organism comprised of interconnected systems) reflects advanced thinking about ecology expressed by John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts in Sea of Cortez. For that matter, Tortilla Flat presages the small-group collectivism espoused by Russell Brand in Revolution, and Travels with Charley suggests the same connections between consumerism, conflict, and unhappiness drawn by Brand and Naomi Klein in their books. Events have caught up with John Steinbeck’s prophecy; as I write, his beloved city of Paris remains on security alert following the Charlie Hebdo massacre, and Agence France-Presse reports that the richest one percent of the world’s population will own half of the world’s wealth by next year. Like John Steinbeck, Russell Brand and Naomi Klein wish to advise us of disaster ahead.

Like John Steinbeck, Russell Brand and Naomi Klein wish to advise us of disaster ahead.

Russell Brand’s Revolution—Change You Can’t Believe In?

Mention Russell Brand to anyone under 40—the age the hyperkinetic actor, radio host, and comedian will reach in June—and you’ll likely learn about Forgetting Sarah Marshall and Get Him to the Greek, youth-market movies in which Brand played offbeat characters. I’ll show my own age and admit I didn’t know who Russell Brand was until he was called out by Bill Maher (on Real Time with Bill Maher, soon after the 2014 election) for asserting in Revolution that voting is pointless because all political parties have the same agenda: getting and keeping power and protecting moneyed interests. But watching Maher, I recognized Brand’s face from St. Trinian’s, an offbeat British comedy about an anarchic private girl’s school that I enjoyed. In the movie, Brand plays a hyperbolic drug dealer, Colin Firth is a clueless Tory Minister of Education, and Rupert Everett portrays a playboy dad and—in dreadful drag—the school’s pot-smoking headmistress, who is Firth’s love interest as well. Naturally, I bought Brand’s book.

Mention Russell Brand to anyone under 40 and you’ll likely learn about ‘Forgetting Sarah Marshall’ and ‘Get Him to the Greek,’ youth-market movies in which Brand plays offbeat characters.

When I learned more about Russell Brand, his role in St. Trinian’s made sense. Turns out he’s an up-from-poverty populist with an ability to talk fast, a history of alcohol and drug abuse, and a slight criminal record—sort of an updated character from Tortilla Flat, but with an East London accent. As a thinker Brand firmly believes in benevolent anarchy, the form of social reorganization he recommends in Revolution. As a speaker and writer he manages, like John Steinbeck, to mix high-level messaging with low-level language, similar to the chatty social outcasts who populate Cannery Row. Also like Steinbeck, Brand attributes greed and consumerism to spiritual causes embedded in the human condition. This is where John Steinbeck’s friend Joseph Campbell, the anthropologist of myth-making, comes in handy for Brand, a recovering alcoholic whose 12-step program for curing income inequality (Chapter One: “Heroes’ Journey”) rests on spiritual insights found in the world’s great religions and literature. William Blake, whose visionary poetry particularly appealed to John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts, is mentioned frequently in the same vein.

As a thinker Brand firmly believes in benevolent anarchy, the form of social reorganization he recommends in ‘Revolution.’

I marked my copy of Revolution as I read along because so much that Russell Brand says is, like his movie roles, so entertaining. And while he’s perfectly aware of the paradox that he’s trashing capitalism in a product published by an affiliate of the media conglomerate Bertelsmann, it wouldn’t be fair to discourage other buyers by over-quoting from the book. (Also, as Brand might observe, there’s them corporate lawyers, so look out.) Brand’s serio-comic perceptions are memorable because they mix things up, Tortilla Flat-like. Here are a few examples, chosen because they connected with John Steinbeck, Joseph Campbell, Blake, or my funny bone:

“We are living in a zoo, or more accurately a farm, our collective consciousness, our individual consciousness, has been hijacked by a power structure that needs us to remain atomized and disconnected.”

“Campbell said, ‘All religions are true in that the metaphor is true.’ I think this means that religions are meant to be literary maps, not literal doctrines, a signpost to the unknowable, a hymn to the inconceivable.”

“At some point in the past, the mind has taken on the duty of trying to solve every single problem you are having, have had, or might have in the future, which makes it a frenetic and restless device.”

“The alarm bells of fear and desire are everywhere; these powerful primal tools, designed to aid survival in a world unrecognizable to modern civilized humans, are relentlessly jangled.”

“At some Anglican sermon in Surrey, the ‘file-down-the-aisle, handshake-and-smile’ ending is the energetic climax of proceedings. After a polite rendition of ‘Jerusalem’ (in which Blake was apparently being sarcastic) or ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ (which Stewart Lee breaks down beautifully), there isn’t a moment of postcoital awkwardness where everyone thinks, ‘F*** me, we really let ourselves go here.’”

And that’s only from the first five chapters. There are 33 in all, and there are no asterisks in any of them, suggesting a P-13 rating if the book were a motion picture. In a hostile review, The Guardian newspaper dismissed Revolution as “The barmy credo of a Beverly Hills Buddhist.” Then again, the London paper’s online logo boasts that it’s a past “Winner of the Pulitzer prize,” information that Russell Brand would probably identify as a sign of deep-seated corporate insecurity, and that John Steinbeck, who won a Pulitzer for The Grapes of Wrath and disliked self-promotion, would also find deeply unimpressive. Newspapers were economic enterprises with political agendas in Steinbeck’s view, one based on bitter personal experience, and certain media moguls particularly bothered him. The Grapes of Wrath could be characterized as “the barmy complaining of a Los Gatos liberal” and was called worse in print; Steinbeck went out of his way to disparage (without identifying) the ruthlessly acquisitive California publisher William Randolph Hearst, the Rupert Murdoch of Steinbeck’s day. Brand, like Naomi Klein, calls out Murdoch by name for creating the global media machine that protects the interests of predatory capitalism and right-wing politics everywhere: a Citizen Kane on steroids.

The Guardian newspaper dismissed ‘Revolution’ as ‘The barmy credo of a Beverly Hills Buddhist.’ Then again, the London paper’s online logo boasts that it’s a past ‘Winner of the Pulitzer prize,’ information that Russell Brand would identify as a sign of deep-seated corporate insecurity, and that John Steinbeck, who won a Pulitzer for ‘The Grapes of Wrath’ and disliked self-promotion, would also find deeply unimpressive.

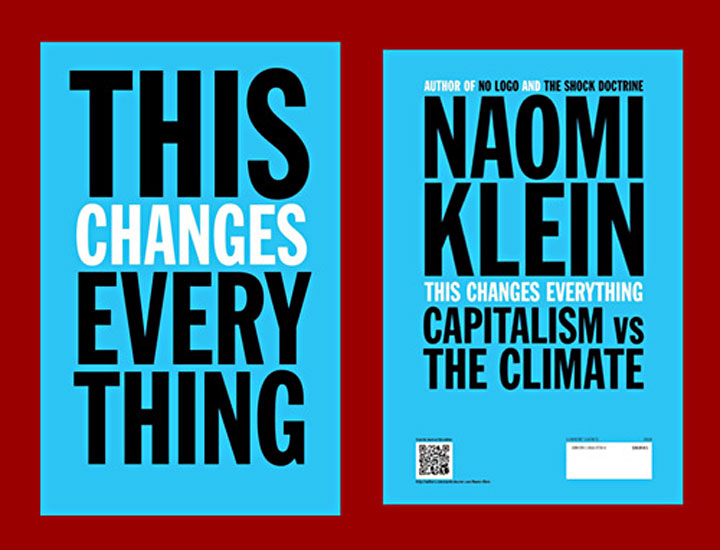

Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything: Third Hit in a Row

This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate got better reviews. The medium is the message, and the book’s careful composition reflects the contrast between Naomi Klein’s polish and Russell’s brand of craziness. He’s hot, hyperactive, and can seem hostile, even with a bath towel draped around his naked neck on his daily YouTube news show, The Trews. Naomi Klein is cool, calm, collected—the daughter of American professionals who left for Canada during the Vietnam War. Brand grew up on the mean streets of East London with a struggling but doting mum and a step-dad. Naomi Klein’s mother is a documentary filmmaker and her father is a physician; both are social activists committed to global causes. In May, Klein will be 45, one month before Russell Brand turns 40. His previous books were wacky children’s stories; hers—No Logo (2000) and The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (2007)—are already considered classics of contemporary cultural criticism. She writes well and she writes often, for The Nation, Harper’s, and—yes—The Guardian; Russell Brand’s mode is oratory, on stage, on radio, and on YouTube. He’s poetry, she’s prose. Other than not bothering to finish college, neither one remotely resembles John Steinbeck in background or personality. But both share Steinbeck’s anger about income inequality, environmental degradation, and social injustice, writing from rage without being inhibited by academic or institutional affiliations.

‘This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate’ got better reviews. The medium is the message, and the book’s careful composition reflects the contrast between Naomi Klein’s polish and Russell’s brand of craziness.

After viewing Russell Brand’s daily Trews segment this morning—a denunciation of military-industrial profiteering and health-service cost-cutting in Great Britain—I dialed back to his October 15, 2014 podcast with Naomi Klein about her then-new book. Her clear, controlled answers to his exuberant questions were just like her writing: comprehensive, linear, and built on solid research, including copious sources, vigorous narrative, and clusters of checkable statistics. The New York Times praised This Changes Everything as “a book of such ambition and consequence that it is almost unreviewable.” The same can be said of Klein’s earlier books. No Logo (“No Space, No Choice, No Jobs”) explores corporate branding from various vantage points—economic, psychological, sociological, political—and turns up a goldmine. The Shock Doctrine connects the dots between Cold War American interventionism, both covert and undeclared (as in Chile under Pinochet), George Bush’s Halliburton-helping invasion of Iraq, and post-Katrina profiteering by firms like Blackwater. Henry Kissinger, the architect of U.S. shock-doctrine foreign policy, and Milton Friedman, the father of free-market economic ideology, receive the close attention the human damage they caused deserves.

The New York Times praised ‘This Changes Everything’ as ‘a book of such ambition and consequence that it is almost unreviewable.’ The same can be said of Klein’s earlier books.

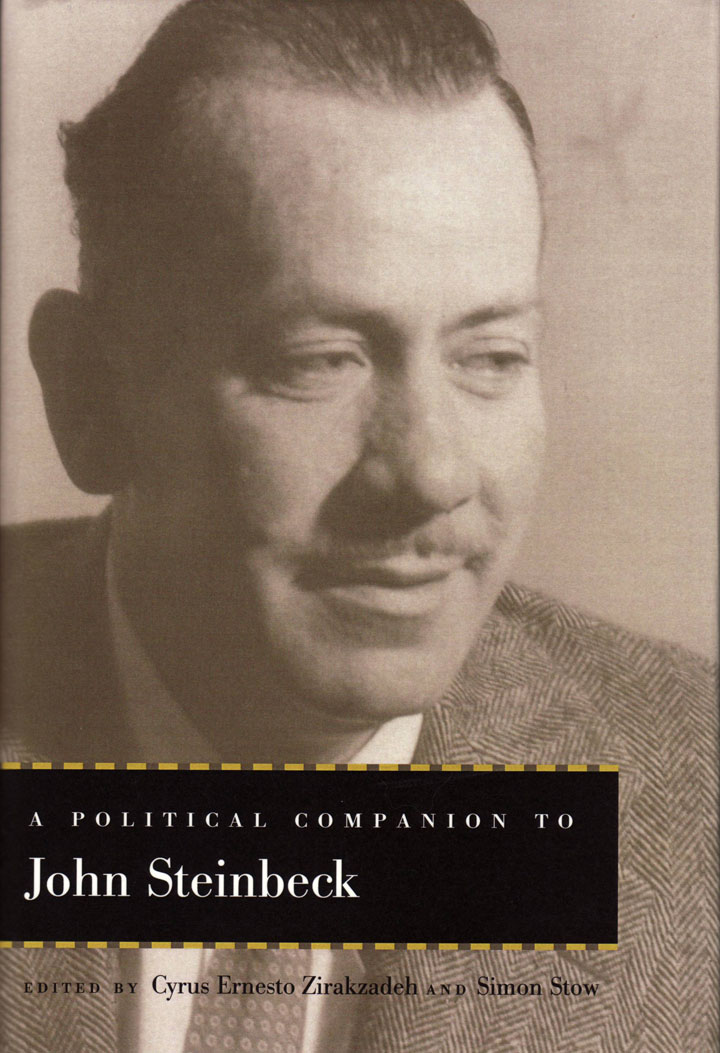

John Steinbeck’s public support for American intervention in Vietnam—pre-Friedman and pre-Kissinger—continues to trouble the author’s admirers. Based on private correspondence, however, there’s little doubt that Steinbeck had his doubts about the war’s wisdom or justification, or that he might eventually have come around to Naomi Klein’s parents’ point of view. He was no friend of torture, assassination, or reactionaries, either; we can be confident that Klein’s compelling critique of Margaret Thatcher’s England, George W. Bush’s America, and Vladimir Putin’s Russia would resonate with him if he were alive. As Russell Brand would say, laissez-faire only sounds like a laid-back street party; it’s actually quite dangerous. As political and economic doctrine, it encourages corporate cronyism, induced-disaster opportunism, and national-security statism on an Orwellian scale. Brand and Klein remind us that the unfortunate evidence can be found on the ledgers of both political parties in the U.S., on both sides of the aisle at Westminster, and in both major post-Communist nations, Russia and China.

Perhaps Russell Brand is right, then: why bother to vote if the outcome will always be the same? As Klein notes, even conservatives make concessions to personal freedom (gay marriage, for example) to keep the public’s nose out of Wall Street’s business, which is avoiding regulation, breaking rules, and increasing income inequality. I know, this part’s a bit confusing, because laissez-faire economics is called neo-liberalism in Europe, rendering the term useless in discussing the economic implications of American politics. (Milton Friedman, the right wing’s Karl Marx, was a neo-liberal. Go figure.) John Steinbeck supported liberal politicians all his adult life—Roosevelt, Stevenson, Kennedy—and he actively disliked neo-liberal conservatives like Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon, who would be considered too moderate by Tea Party members today. I’m pretty sure Steinbeck would argue with Russell Brand about not voting, but I’m equally certain he would agree with Naomi Klein’s analysis of the Arab-Israeli conflict over Palestine, where he wrote some of his most interesting travel commentary before the Six-Day War that changed the political landscape of the Middle East, it would appear permanently.

John Steinbeck supported liberal politicians all his adult life, and he actively disliked neo-liberal conservatives who would be considered too moderate by Tea Party members today.

In a sense, This Changes Everything is a continuation of the cultural narrative begun in The Shock Doctrine. Indeed, Naomi Klein’s books can be read (and I recommend this) as a single meta-story, not unlike the alternating narrative and intercalary chapters in The Grapes of Wrath. The social and environmental consequences of laissez-faire economics—perpetual armed conflict, growing income inequality, cataclysmic climate change—all flow from a singe source in both interpretations of current events: the enshrinement of personal greed as a political philosophy, employing all of the tools that government, media, and private wealth possess to reshape collective consciousness and reify the status quo. James Lovelock, the author of the earth-as-organism theory that I first heard about in college biology, was and is a sunny optimist, now approaching the age of 96. But as John Steinbeck knew, hope can be a commodity too.

In a sense, This Changes Everything is a continuation of the cultural narrative begun in The Shock Doctrine. Indeed, Naomi Klein’s books can be read (and I recommend this) as a single meta-story, not unlike the alternating narrative and intercalary chapters in The Grapes of Wrath. The social and environmental consequences of laissez-faire economics—perpetual armed conflict, growing income inequality, cataclysmic climate change—all flow from a singe source in both interpretations of current events: the enshrinement of personal greed as a political philosophy, employing all of the tools that government, media, and private wealth possess to reshape collective consciousness and reify the status quo. James Lovelock, the author of the earth-as-organism theory that I first heard about in college biology, was and is a sunny optimist, now approaching the age of 96. But as John Steinbeck knew, hope can be a commodity too.

James Lovelock, the author of the earth-as-organism theory, was and is a sunny optimist, now approaching the age of 96. But as John Steinbeck knew, hope can be a commodity too.

When John Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath, Sea of Cortez, and later Cannery Row, war and drought and despair seemed liked passing phases, misfortunes to be confronted and endured and survived. Now, three-quarters of a century later, are we still that sanguine about the future? As Naomi Klein demonstrates in This Changes Everything, the global climate clock is ticking, and the accumulated power of the international petroleum industry prevents the reformation of human belief and behavior required to slow it down. I’m glad she picked Bill Gates and Virgin’s Richard Branson for special scorn in her book. As she shows, each is a wolf in liberal’s clothing when it comes to meaningful action in the current crisis: the billionaires won’t save us when the oceans rise, she proves that for sure. If not reform—as John Steinbeck warned us in The Grapes of Wrath, then what? Revolution?