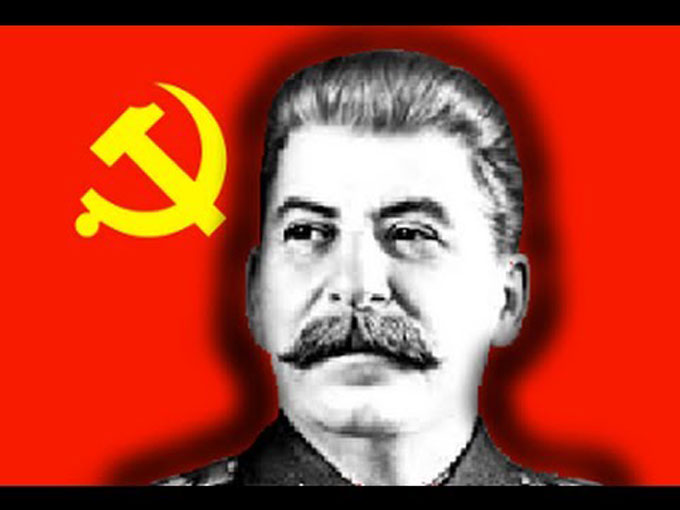

Donald Trump said weather kept him from wreath-laying duty at the American cemetery outside Paris on the 100th anniversary of the armistice that ended the Great War. But the rain-shy Make-America-Great-Again president managed to keep his Armistice Day date in Paris with Vladimir Putin, the former KGB officer who runs Russia the way Stalin did when John Steinbeck and Robert Capa toured the Soviet Union 70 years ago. Previously undisclosed details of KGB spying on Steinbeck and Capa emerged from a recently declassified document summarized in a Radio Free Europe report that should stir anyone anxious about Russian history repeating itself in the love affair between Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump. (For a dose of relief, see Stephen Cooper’s blog post on finding solace in Steinbeck published by The Hill in 2016.)

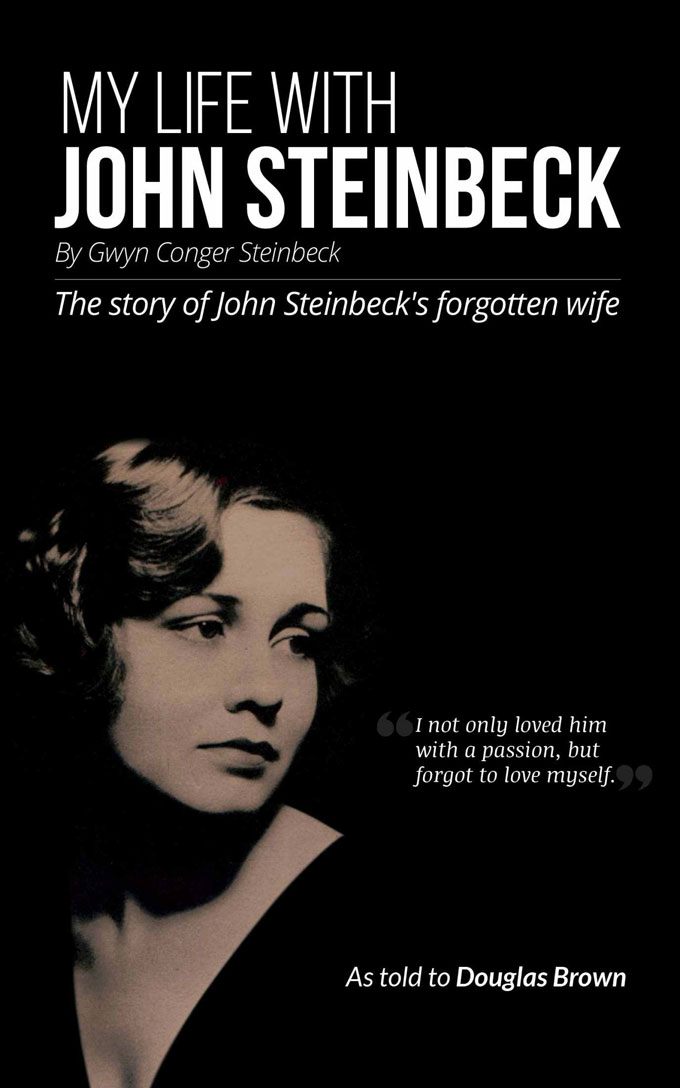

Latest Book About John Steinbeck Honors No One

The publication of My Life with John Steinbeck, a kiss-and-tell marriage tale from the second wife’s point of view, is likely to raise more dust than it settles in Steinbeck country. Based on an edited transcript by the British reporter who taped interviews with Steinbeck’s second wife, Gwyn Conger Steinbeck, the book has a family-feud slant and an origin story that scholars and survivors have probable cause to challenge. A typescript of the taped interviews, which took place in 1971, has been out since 1976, in the form of a graduate student thesis readily available to researchers at various libraries and Steinbeck centers. Douglas Brown—the journalist hired by Gwyn to ghostwrite her memoir, then fired—was back in Britain when he passed away, in the 1990s, without ever publishing his rewrite of her account of an affair that started when Steinbeck was married to Carol Henning and ended in divorce, legal wrangling, and the birth of sons, now deceased, who both became writers. According to London’s Daily Mail, Douglas Brown passed the manuscript to his daughter before he died. She gave it to an uncle in Wales who showed it to a neighbor named Bruce Lawson, the man whose decision to publish now, 50 years after John Steinbeck’s death and 43 years after Gwyn’s, honors neither.

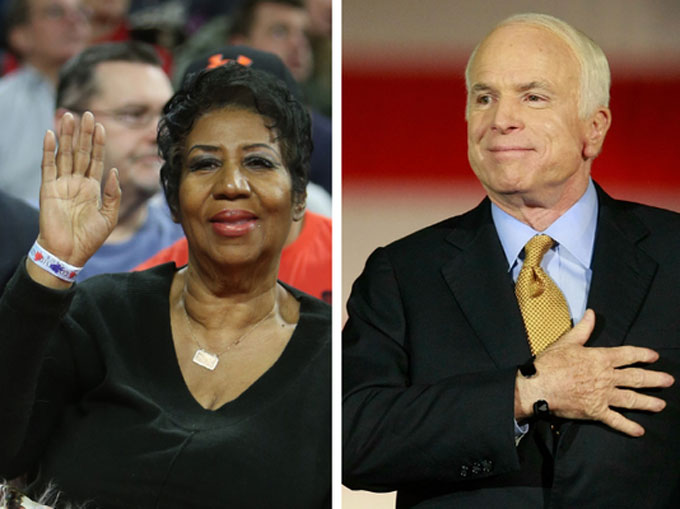

Funeral Services for Aretha Franklin and John McCain Echoed John Steinbeck

Bill Clinton spoke, Stevie Wonder sang, and there was dancing in the aisles at Greater Grace Temple for Aretha Franklin’s funeral in Detroit on Friday. That was hardly the style of the service for John McCain held at Washington’s National Cathedral today, however. Barack Obama and George Bush eulogized their former rival with discretion. “Danny Boy” was delivered, with care, by a former opera star. The camera caught dignitaries in the audience—among them a current cabinet member and a former secretary of state—nodding off in their seats. But no one danced at John Steinbeck’s funeral 50 years ago either. Like McCain, Steinbeck ordered a by-the-book Episcopal service for himself before he died. Both of his sons served in Vietnam, like McCain, and he declined to criticize a war he doubted could be won out of the same sense of duty. Yet he was vocal about civil rights, and his death in 1968 followed that of Martin Luther King, Jr., the motivating inspiration for everyone in attendance at Aretha Franklin’s event, and for the most memorable speaker at John McCain’s. He liked opera and jazz equally, and he missed hearing music at the funeral of his friend Adlai Stevenson in 1965. The services for John McCain and Aretha Franklin this week had different beats for sure. But they marched in the same direction—toward hope for justice. They were singing Steinbeck’s song.

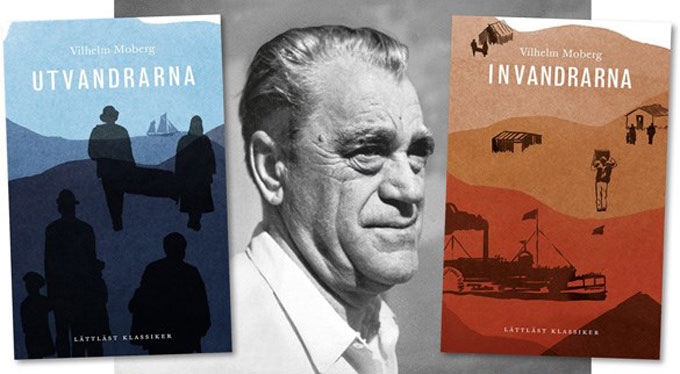

Parallels Meet: Steinbeck, Moberg, and Two Migrations

Steve Hauk, the author of Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, contributed to this account of an overlooked aspect of John Steinbeck’s life, writing, and reputation as a 20th century American internationalist: his association with the Swedish writer Vilhelm Moberg, with whom he shared political sympathies, geographical proximity, and personal traits, including depression.—Ed.

John Steinbeck and Vilhelm Moberg had more in common than literary greatness. Sensitive to the humble, powerless, and downtrodden, both writers documented social injustice with abiding sympathy and convincing clarity in works of fiction that became classics. Both wrote novelistic sagas of human migration that became major movies—Steinbeck’s 1930s protest novel The Grapes of Wrath and The Emigrants, the series of four novels in Swedish written by Moberg and made into a pair of feature films starring Liv Ullmann and Max von Sydow in the 1970s. Both men did some of their best writing on California’s Monterey Peninsula, though at different times, and may have met there in the late 1940s. “In one of his letters home, Moberg mentions having met Steinbeck,” notes Swedish scholar Jens Liljestrand, who speculates that the meeting must have been “brief and superficial,” given the barriers of language, age, and demeanor that separated them.

Both men did some of their best writing on California’s Monterey Peninsula, though at different times, and may have met there in the late 1940s.

Steinbeck died in 1968 at 66, and Moberg, who was born in 1898, committed suicide in 1973. But one thing is certain. If they were alive today both men would be deeply disturbed by the global refugee crisis and the resurgent nativism that has nurtured anti-immigration movements in Sweden, the United States, and across Europe. While Steinbeck focused on a family of Oklahoma tenant farmers driven west by natural catastrophe and Depression economics, Moberg followed a family of Swedish farmers who abandon the stony soil of Smaland in the 1800s for the promised land of rural Minnesota. Both took sides in parallel stories of epic struggle—for survival, dignity, and a place to call home. In each case, the dream of land and domicile motivated migration across states or seas by displaced souls, described most poignantly in the African American spiritual “Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child.”

Both took sides in parallel stories of epic struggle—for survival, dignity, and a place to call home.

When Vilhelm Moberg came to California in 1948, the Monterey Peninsula was about to face its own disaster—the depletion of the sardine population through over-fishing predicted by John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts, who died the year Moberg arrived. Gustaf Lannestock, a Swede who had worked as a masseur at the Hotel Del Monte and moved to Carmel, met Moberg walking on the beach and became his friend and translator. In 1998, the late Monterey County Herald columnist Bonnie Gartshore described the fateful encounter: “One day in 1948, Vilhelm Moberg, Sweden’s foremost novelist, took a rest from writing “Utvandrana” (“The Emigrants”). He had come to the Monterey Peninsula after long months of research to write the book, first of a [quartet] about Swedish families . . . in the 1800s. One way of relaxing after intense writing stints was to plunge into the surf at Carmel Beach.’’

Moberg came to the Monterey Peninsula to write a book about Swedish families in the 1800s.

When Steinbeck lived in Pacific Grove in the 1930s he sought relief in the same fashion, exploring the tide pools with his friend Ricketts and gaining a sense of proportion. Lannestock and his wife Lucile enjoyed Swedish-style entertaining and their home attracted a party crowd, described by Liljestrand as the “cultural elite in Carmel,” that included Ricketts—who wrote of his friendship with Lannestock—and Steinbeck, as well as Robinson Jeffers. But according to Moberg, notes Liljestrand, the Lannestocks “didn’t socialize much with Steinbeck” because “they took his estranged wife’s side” when the Steinbecks moved to Los Gatos and their marriage collapsed. Steinbeck’s career eventually took him to Hollywood, Mexico, and Manhattan. He completed East of Eden, the California saga of his mother’s Irish-immigrant farm family, in New York. Moberg—who based his quartet of Swedish emigrant novels on the diaries of a Minnesota farmer—had finished the first two (shown here) in Carmel by 1952, the year East of Eden appeared.

When war came, neither Moberg nor Steinbeck was afraid to speak out. Moberg was openly critical of Sweden’s attempt at neutrality, and his 1941 novel Ride This Night, though set in the 17th century, is clearly a commentary on Nazi aggression. Steinbeck’s 1942 novella The Moon Is Down is about the invasion of an unnamed town in Scandinavia by an unnamed army that is unmistakably German. The book was outlawed in occupied Sweden, where Steinbeck had friends, but contraband copies were passed by hand and Steinbeck’s contribution to European morale was cited when he received the Nobel Prize from the Swedish Academy. The Steinbeck-Moberg connection can also be seen in Arvid and Robert, characters in The New Land who, as the film critic Terrence Rafferty observed, “have come to resemble Lennie and George, the wanderers of John Steinbeck’s ‘Of Mice and Men’” in the 1972 motion picture adaptation of the second novel in Moberg’s emigrant series. The movie’s director was Jan Troell, a Swede who shared Steinbeck and Moberg’s vision of the emigrant experience—and who came to the Monterey Peninsula in 1974 to shoot Zandy’s Bride, also starring Liv Ullman.

When war came, neither Moberg nor Steinbeck was afraid to speak out.

Swedes are supposed to be solitary types who wait for others to break the ice, a function frequently served by friends like Lannestock and Ricketts, Moberg’s likely entrée to Steinbeck’s world. “According to Lannestock’s memoir,” notes Liljestrand, “Moberg’s English wasn’t very good. He mostly hung out with just the Lannestocks, with whom he spoke Swedish.” If Bonnie Gartshore is correct, Moberg made his way despite that obstacle. In Monterey, she says, “he enjoyed talking to Sicilian Fishermen whom he met on Fisherman’s Wharf, and he wrote an article about them for a Stockholm newspaper.” Devastated by the death of Ricketts and a second failed marriage, Steinbeck returned to Pacific Grove in 1949 to recover. Given their habit of taking walks, a meeting with Moberg could have occurred by accident. Given their reticence, it might have needed help.

Lannestock and Ricketts were Moberg’s likely entrée to Steinbeck’s world.

Like Steinbeck, Moberg enjoys an enduring reputation in the homeland he both criticized and celebrated in his writing. His novels are required reading in Sweden, where he’s revered as a journalist, historian, and playwright with more than two dozen dramas to his credit. Also like Steinbeck, he experimented with literary forms. Steinbeck will always be associated with Okie migration and intercalary structure for The Grapes of Wrath. The author who called The Emigrants series his “documentary novels” became synonymous with Swedish immigration to the United States. Neither writer was satisfied by the celebrity. In a letter to Toby Street, Steinbeck talked about “a longing for extinction” caused by the conviction he “had no home, never did”—cruelly ironic from one who, like Moberg, wrote so memorably of people searching for a home.

Neither Steinbeck nor Moberg was satisfied by the celebrity they achieved.

Like Steinbeck, Moberg suffered from depression that grew worse with age. A radical democrat and political contrarian, he continued to speak out against monarchy, bureaucracy, and public corruption after he returned to Sweden. But he experienced writer’s block and his melancholy became despair. Early one morning in 1973 he left a letter of apology for his wife and drowned himself. “The time is twenty past seven; I go to search in the lake for eternal sleep. Forgive me, I could not endure,” he wrote her. He is frequently paired with his fellow Scandinavian O.E. Rolvaag, the author of Giants in the Earth. But he had much in common with his fellow Californian, John Steinbeck. The connection is overlooked, but it extended to war, depression, and epic protest against epic injustice. In light of current events, it’s worth remembering.

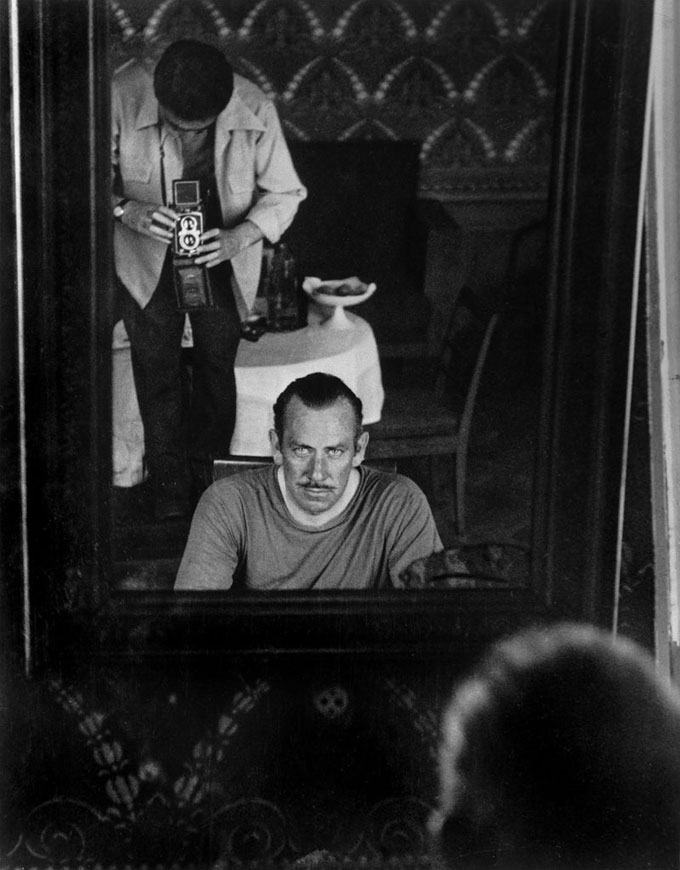

New Republic Updates John Steinbeck and Robert Capa’s Russian Journal in Pictures

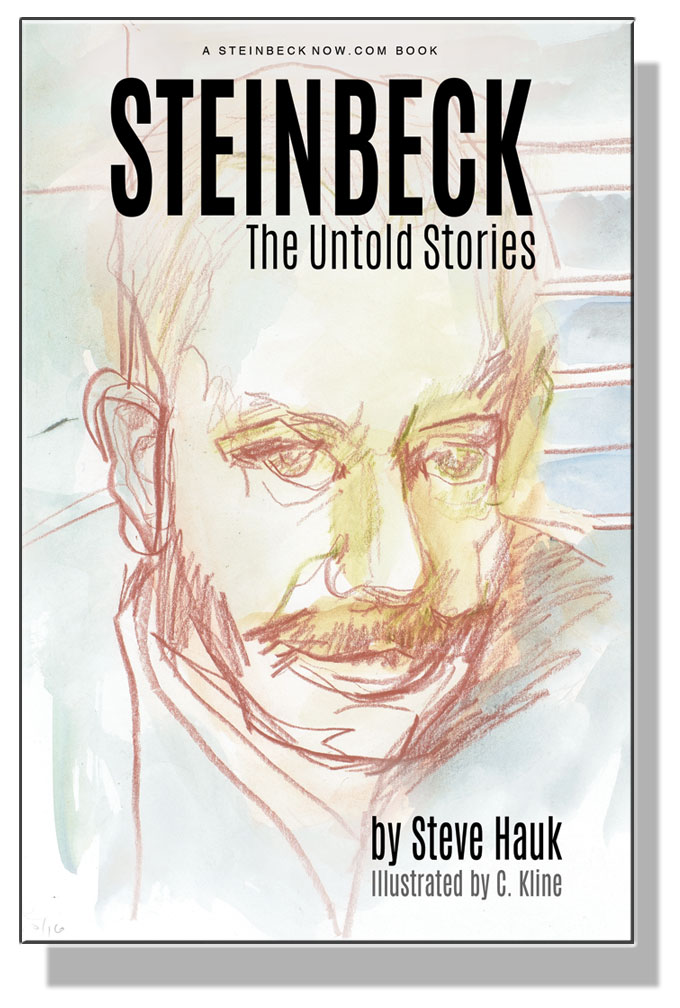

Like John Steinbeck’s 1940 expedition to Baja, California with the marine biologist Ed Ricketts, his 1947 trip to Russia with the war photographer Robert Capa yielded a book that reveals as much about the relationship of the co-authors as it does about the subject. Like Ricketts, Steinbeck’s collaborator in writing Sea of Cortez, Capa was Steinbeck’s boon companion and opposite, equally accomplished and adventurous but lighter on his feet and better with women and strangers. A photo essay published this week in New Republic, 70 years after the publication of A Russian Journal, displays a selection of Capa’s black-and-white images next to color photos taken by Thomas Dworzak when he and Julius Strauss recapped the trip recorded in A Russian Journal to show how Russia has changed since 1947. Steinbeck enjoyed the company of everyday Russians, who weren’t that different from Americans when encountered face-to-face. He also enjoyed Robert Capa, as shown in Capa’s photo of Steinbeck looking at their reflection, a mirror of the relationship revealed in A Russian Journal.

Photograph by Robert Capa courtesy International Center of Photography/Magnum.

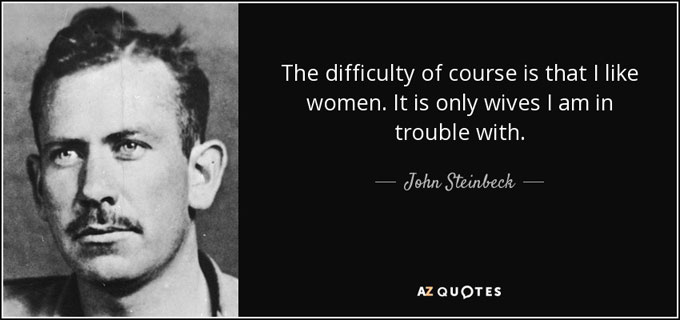

Women in John Steinbeck’s Life on Display in San Jose

Ma Joad in The Grapes of Wrath. Cathy/Kate in East of Eden. Elisa Allen in “The Chrysanthemums.” Such women from John Steinbeck’s fiction are unforgettable. So, on examination, are the women in Steinbeck’s life, as this quotation suggests. Steinbeck’s mother Olive Hamilton and first wife, Carol Henning, were both from San Jose, California, and San Jose State University is celebrating each (and the two wives who followed) in a special exhibit of documents and photographs on the 5th floor of the MLK Library, located on the San Jose State University campus, through January 20, 2018.

To paraphrase the man who bragged about failing his way to success in marrying for the third time, the success of John Steinbeck’s marriage to Elaine Scott, from 1950 until his death in 1968, was possible only because the strong willed mother and wives who preceded her prepared him for their partnership. Some say he married his mother. Steinbeck doubted Freud and disliked psychoanalysis, but he’d be happy to see the women in his life get the credit they deserve for the roles of educator (Olive), editor (Carol), and manager (Elaine) without which his writing wouldn’t be so quotable.

The exhibition may move next to the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California, where the theme of the 2018 Steinbeck Festival (and the inspiration for the MLK Library show) is “The Women of Steinbeck’s World.” The May 4-6, 2018 festival will be held at the Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove, where John Steinbeck and his sister Mary studied biology when they were students at Stanford University. Susan Shillinglaw, professor of English at San Jose State University and director of the National Steinbeck Center, is the author of Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage,

Like Life of John Steinbeck, Interest in Short Stories Is Both Global and Local

Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, a collection of short stories by the California writer and art expert Steve Hauk, continues to attract attention internationally and at home. Artnet, the influential art marketplace website headquartered in New York, focuses on “the gallery owner’s reimagining of John Steinbeck and the contemporary interest in early California art” in a November 8 interview with Hauk, who owns and operates the downtown Pacific Grove art gallery that has become a popular venue for area Steinbeck fans and visitors to the coastal community where the author lived and wrote in the 1930s. The local public library frequented by Steinbeck and his wife Carol is doing its part, too. On November 17, Friends of the Pacific Grove Library will present Hauk’s talk on writing the Steinbeck short stories at a 7:30 p.m. event that is free and open to the public. (Non-members: suggested donation is $10.)

How John Steinbeck’s Name Caused Confusion at the Pacific Grove Post Office

Just the other day she stepped into our Pacific Grove, California gallery with a distinguished-looking gentleman who likes to do carvings. Her name’s Joy and the gentleman was her husband Jerry.

The subject of John Steinbeck came up—as it usually does in the gallery—and Joy said:

“My parents couldn’t stand him.”

“Why not?”

“They’d get late night phone calls from people, usually inebriated, asking for him—for John Steinbeck. Getting them up in the middle of the night infuriated my folks.”

Steinbeck probably would have liked Joy, a school teacher and administrator who has taught and teaches everything from English and business to quilting, because she added with finality: “And that’s all I know about it.”

It reminded me of something Ma Joad might say.

I waited a bit then asked some questions anyway.

Joy said her parents came to Pacific Grove in 1943. Her father was about 37 years old at the time but could have been drafted into the army even though he and his wife Lela had a young child. Someone recommended that he join the post office instead of the army and he did, becoming, eventually, a clerk in the Pacific Grove branch on Lighthouse Avenue, a branch Steinbeck would have used for many of his postal needs in the 1930s—perhaps sending off typescript copies of Tortilla Flat and Of Mice and Men to his publisher in New York.

What, I asked Joy, was her parents’ last name?

“Steinecke,” she said. “It came right after Steinbeck in the phone book.”

“And what was your father’s first name?’

“John,” she said.

It was beginning to come together . . . .

I could see someone in a phone booth looking up the Steinbeck phone number in the middle of the night—maybe to give the author some good advice, not realizing he was now living on the East Coast. Having had a few drinks, the caller could easily morph Steinbeck into Steinecke, or maybe the finger marking the place slipped down the page just a smidge and, hey, it still says John! If the Steinbeck name wasn’t listed, Steinecke would do nicely.

As a result, Mr. Steinecke, scheduled to begin work at the post office in a few hours, gets calls at two, three in the morning. Not easy to get back to sleep, the phone conversations likely still echoing in his head:

“Mr. Steinbeck, I think . . . I think you should change the ending of Tortilla Flat.“

“I’m a postal clerk!”

“I know, but you wrote the book.”

According to Joy, John Steinecke would not have been amused.

“My dad was the grandson of a Prussian general who immigrated from Germany in the mid-1800s,” Joy said. “His sense of humor was not particularly well-developed, and he would probably huff about those phone calls if he were still alive. Anyway, he might not laugh, but he definitely would be pleased that you were writing about him and John Steinbeck.”

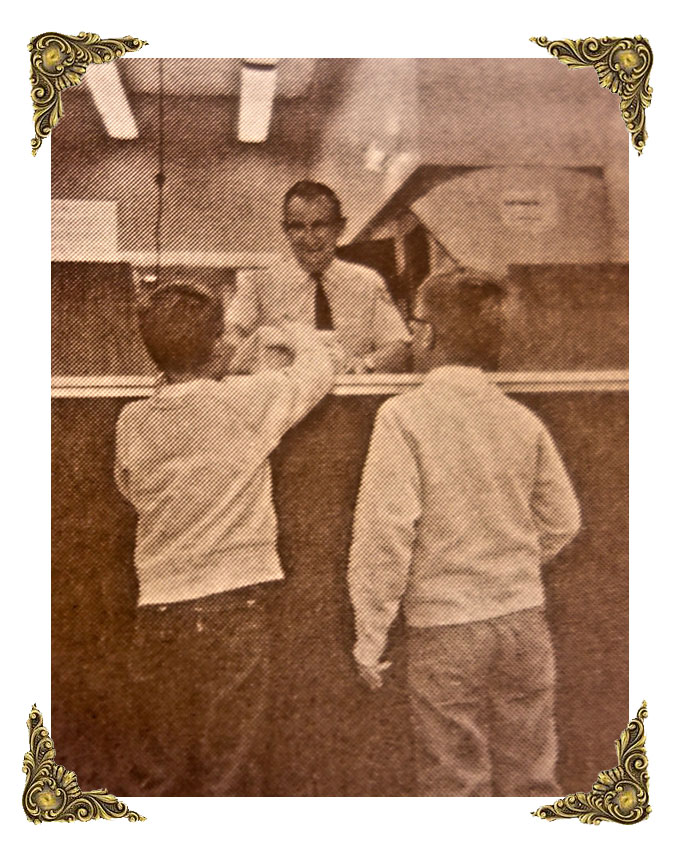

So, on a recent morning, with images of John Steinbeck and John Steinecke dancing interchangeably in my head, I went into the Pacific Grove post office for stamps and spoke with a clerk named Ron. For all I know, Ron was standing where Mr. Steinecke stood decades ago.

Ron said, quite the opposite of what Mr. Steinecke thought in the 1940s, “Steinbeck’s one of my favorites. People recommend other writers, but I always seem to come back to Steinbeck.”

Of course, if Ron had been living back then, working in the Pacific Grove post office, and his name was John Steinecke, even Ron Steinecke, he might have switched his literary allegiance to Hemingway or Faulkner.

Period photo of John Steinecke serving young customers at the Pacific Grove post office from Norton and Gus, by Margaret Hayden Rector (Grossmont Press, 1976).

Stanford University Praises John Steinbeck in Profile of English Prof Gavin Jones

Stanford University—the wealthy private university in Palo Alto, California known for having world-class programs in business, engineering, and medicine—has given a new boost to the literary reputation of John Steinbeck, an erratic English department enrollee who left Stanford in 1925 without a degree. A new online profile of English department faculty member Gavin Jones makes the case for Steinbeck as an undervalued American writer and thinker who was ahead of his time in subject, style, and versatility. “One hundred and fifteen years after his birth in Salinas, California,” the story states, “Steinbeck’s life and work—the latter [of] which has long languished on high school reading lists—is undergoing a revival.” An affable Englishman who recently taught an American studies course at Stanford on Steinbeck and the environment, Jones explains the renewed attraction: “I’d like to think that Steinbeck’s work speaks to students from multiple backgrounds because his interests were so interdisciplinary.” Robert DeMott, the distinguished Steinbeck scholar and poet who also writes about fly fishing, says that Stanford University’s initiative is especially encouraging because Steinbeck teaching and scholarship have traditionally been the province of public colleges such as San Jose State and Ohio University, where DeMott taught generations of graduates including David Wrobel, another English convert to Steinbeck who was recently named interim dean at Oklahoma University. Adds DeMott: “Steinbeck’s recognition by a private university of Stanford’s stature will go far to redress Steinbeck’s underestimation by the literary establishment of his day, and to some extent our own as well.”

Photo of Gavin Jones courtesy Stanford University News Service.

Rousing Post Recalls Cold War, Citing John Steinbeck

“Revisiting John Steinbeck’s A Russian Journal from 1948”—an impassioned website post dated March 21, 2017—reminds readers that John Steinbeck and Robert Capa overcame opposition from left and right in reporting firsthand on daily life in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin following World War II. A publication of the International Committee of the Fourth International, the World Socialist site revives Cold War rhetoric in attacking the forces of fascism, Stalinism, and reactionary capitalism that combined to make the lives of ordinary Russians as miserable as possible before, during, and after the war. The language of the post sounds outdated, but the author’s idea accords with the view of John Steinbeck, whom she credits for accuracy and bravery in the face of threats at home and in Russia. “While the Soviet Union was destroyed more than 25 years ago by the Stalinist bureaucracy,” she writes, “the experiences of the Second World War continue to shape the consciousness of millions in the former USSR. Despite certain limitations, this work by Steinbeck and Capa provides valuable insight into the historical experiences of the working class and peasantry of the former USSR.” Timely praise.

“Revisiting John Steinbeck’s A Russian Journal from 1948”—an impassioned website post dated March 21, 2017—reminds readers that John Steinbeck and Robert Capa overcame opposition from left and right in reporting firsthand on daily life in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin following World War II. A publication of the International Committee of the Fourth International, the World Socialist site revives Cold War rhetoric in attacking the forces of fascism, Stalinism, and reactionary capitalism that combined to make the lives of ordinary Russians as miserable as possible before, during, and after the war. The language of the post sounds outdated, but the author’s idea accords with the view of John Steinbeck, whom she credits for accuracy and bravery in the face of threats at home and in Russia. “While the Soviet Union was destroyed more than 25 years ago by the Stalinist bureaucracy,” she writes, “the experiences of the Second World War continue to shape the consciousness of millions in the former USSR. Despite certain limitations, this work by Steinbeck and Capa provides valuable insight into the historical experiences of the working class and peasantry of the former USSR.” Timely praise.