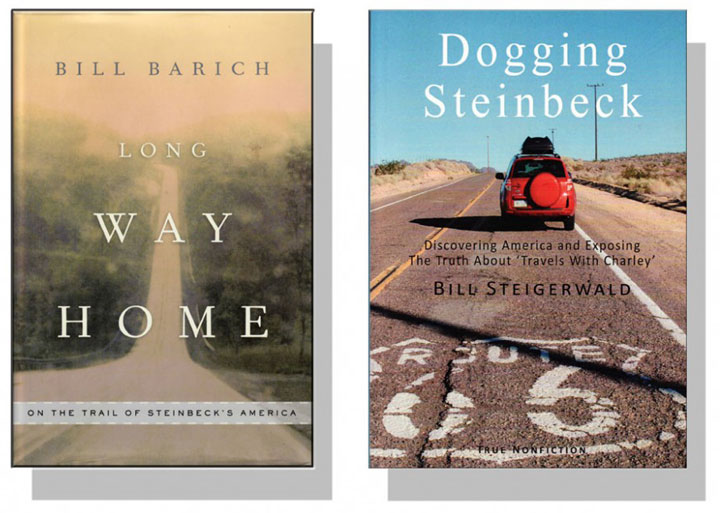

John Steinbeck’s brand remains a resilient commodity with commercial uses that continue to surprise. Steve Hauk alerts Steinbeck lovers to J. Crew’s online profile of Carla Sersale, a clothing designer whose family owns a summer resort on the Amalfi Coast, a magical place visited by John Steinbeck in 1953. Along with the view, the hotel’s rooms feature specially bound copies of John Steinbeck’s piece on Positano, Italy, written for Harper’s Bazaar magazine—a reminder that Steinbeck knew how to travel well and commercialize, too.

Pulitzer Prize Finalist Writing John Steinbeck Biography: Talk With William Souder

Plans to publish a new John Steinbeck biography by William Souder, a Pulitzer Prize finalist for Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of The Birds of America, received wide attention for good reason. When Souder’s John Steinbeck biography is released by W.W. Norton & Company in 2019, Jackson Benson’s classic life of Steinbeck will already be 35 years old. Jay Parini’s 1995 John Steinbeck biography covered some of the same ground, but Benson’s experience with Steinbeck’s heirs may have intimidated other biographers, delaying reinterpretation of Steinbeck’s life and work for contemporary readers more interested in new information than old quarrels. On a Farther Shore: The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson, Souder’s brilliant biography of the crusading ecologist who wrote the 1962 book that made environmentalism a burning issue, promises to connect ecology, Steinbeck, and the so-called American century, renewing appreciation and deepening our understanding of a troubled writer who seemed, almost equally, behind and ahead of his turbulent time. Like John James Audubon, John Steinbeck was a complicated man who sometimes managed to cover his tracks. Like Rachel Carson, Steinbeck was a passionate dissident who championed change, challenged power, and suffered the consequences. In this interview, William Souder explores the connections and compares the three figures, explaining why (and how) he is writing a new John Steinbeck biography now.

WR: Your John Steinbeck biography will be titled “Mad at the World: John Steinbeck and the American Century.” How was this title chosen, and what does it tell us about your approach?

WS: Titles are important. Sometimes it comes to you easily at the start, and other times you struggle to find the right one. With Steinbeck I had this title almost from the moment I decided to write about him. There’s the obvious meaning—that Steinbeck wrote in response to the injustice and evil he saw in the world. That’s clearly true in books such as In Dubious Battle, The Grapes of Wrath, East of Eden, and The Winter of Our Discontent, a book I regard highly, and that contains some of Steinbeck’s most elegant prose. Of course, most writers concern themselves in some way with the ills of the world. Steinbeck seemed to take it more personally. He was, especially when he was young, prickly. Not bad-tempered, but running a couple of degrees hotter than everyone else. He bridled at conformity—his deep friendship with Ed Ricketts was based in large part on their shared hatred of convention. Steinbeck didn’t like school, didn’t like Salinas, didn’t like working as a reporter in New York. And all of those things didn’t like him back. Stanford was happy to be rid of him when he finally gave it up. Later, people in California thought The Grapes of Wrath was obscene and filled with lies. Steinbeck pretended to ignore criticism, but no writer actually can. When he said he didn’t think he deserved the Nobel Prize I don’t believe he really meant it. I think he just wanted to disarm the critics who were lining up to say as much. Of course, they said it anyway.

One of the things that attracted me to Steinbeck is that he was far from perfect—as a man, a husband, a writer, he had issues. He had a permanent chip on his shoulder. He got sidetracked by ideas that were a waste of his time and talent. Some of his work is brilliant and some of it is awful. That’s what you want in a subject—a hero with flaws. Steinbeck was a literary giant who wouldn’t play along with the idea that he was important. I love that. He was mad at the world because it seemed somehow mad at him.

Anyway, I think it’s a strong, provocative title. And I hope it explains that I want to place Steinbeck firmly in the historical context that was the wellspring for so much of his work.

WR: Like Steinbeck’s father, you spent your early life in Florida but moved away. Where, when, and how did you become a writer?

WS: I did grow up in Florida, but I was actually born in Minnesota. My dad was an aerospace engineer, and we moved to Florida when the space program got going in the late 1950s. I loved it there, the beaches and the Gulf of Mexico, and the scent of orange blossoms in the warm night air. Florida will always be home to me, but I’ve lived in a lot of places. I married a girl from St. Paul and once you do that you’re committed to the tundra. I’ve been in Minnesota now for longer than anywhere else. It has a lot going for it, though in the winter it’s like living on another planet. We’re out in the country, with the coyotes and the wide open spaces, and the dark, dark starry nights. Our neighbor still cuts hay on our property. But we can see the Minneapolis skyline from our house—in fact I’m looking that way right now.

I got interested in film and photography and writing after I got out of the Navy. I went to the journalism school at the University of Minnesota, which at the time was among the best j-schools in the country, and where you could study all of those things. This was right after Woodward and Bernstein had turned journalism into a glamorous profession. There was a legendary professor there named George Hage—he’s long deceased, but still remembered here as an inspiration to several generations of journalists—who was a mentor to me and who convinced me to become a reporter. Which I did. Then, in 1996, a story I wrote for the Washington Post turned into my first book. I was 50 when it came out four years later and I didn’t look back.

WR: Your first book was about a local ecological catastrophe. How did that lead to writing a life of John James Audubon, who could hardly be characterized as an environmentalist?

Let’s pull the curtain back. For many writers, it only looks like one book naturally follows another. The truth is that, in between, there are often false starts and dead ends. Ideas that don’t pan out. Concepts that your agent or your editor—or both—don’t like. I’ve sold four books to publishers, but I’ve had probably twice that number rejected, though most of them in the early, talking stages, when I had little invested. Some of those ideas probably deserved to die, but with others I wonder what might have been. At one point I was determined to write a book about hurricanes. I had plenty of firsthand experience with hurricanes growing up in Florida, and I wanted to get inside a big storm by flying with the Hurricane Hunters out of Miami. But my editor didn’t think it would work and I moved on. Later that year, Katrina hit New Orleans.

My interests are science—especially biology—the environment, history, and writers. So I look for subjects that embody those interests. That’s the common thread in all of my books, and it applies to John Steinbeck, too. It’s true that Audubon was no environmentalist. Nobody was back then. But he was, in addition to being a great painter, a naturalist and explorer and ornithologist who was immersed in what we call “the environment,” which is really just the world as it is—including the damage we do to it.

WR: Your biography of John James Audubon was a Pulitzer Prize book finalist. Winning the Pulitzer Prize seemed to surprise Steinbeck and disrupt relationships in his life. Did making the Pulitzer Prize short list influence your choice of subject for your next book?

WS: Being a finalist for the Pulitzer means your book was one of three nominees for up for consideration. One book wins, the other two are the finalists. So it’s a select group and an honor. And it did have one important effect on my future work: It confirmed for me that I could write biography, a discipline I didn’t know anything about until I did the Audubon book, but which I fell in love with. It turns out that I have that gene that makes you willing to spend weeks or months in an archive crawling around inside someone else’s life. And when you do that, and that other life becomes a story you have to tell, you know you’re cut out for biography.

You do choose your subjects. Absolutely. And there can be a lot of calculation in it. You’re searching for a book that you want to write and that people will also want to read. But for it all to come together, on some level your subject has to choose you. I started thinking about writing about Rachel Carson around 2005. But I wanted to time that book so it would come out in 2012, on the 50th anniversary of Carson’s Silent Spring. I figured I had time to write one, or maybe two other books before turning to Carson. But a couple of ideas didn’t work and by 2008 I realized it was time to start on Carson. She left a rich paper trail—most of it is at the Beinecke library at Yale, one of my favorite places in the world—and the more I looked at the material the more insistent it became. Once someone’s life gets inside your head you can’t shut it off. It’s like hearing a voice. Let’s do this now.

WR: Your John James Audubon book is also a biography of frontier America’s adolescence. What motivated the leap from 19th century to 20th century America in your decision to write about Rachel Carson?

WS: In my mind, Audubon and Carson have deep connections to each other. Audubon recorded, in his remarkable bird paintings and in what he wrote to accompany those images, an American landscape largely unmarred by civilization. A century later, Rachel Carson surveyed that same landscape—first as a writer for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and later as the author of Silent Spring—and found it damaged. With Silent Spring, she almost singlehandedly launched the modern environmental movement. And that movement has as its objective the preservation of a natural order that Audubon took for granted. We will never get there, but Carson started us in the right direction. A good friend of mine who is a biologist once told me that our job is not to save the world, but to save ourselves. Audubon showed us why; Carson showed us how.

WR: What were the hardest parts of researching the lives of Rachel Carson and John James Audubon for publication, and how did your research methods differ in writing the two books?

WS: I’ve got a good answer, which sort of true, and a boring answer, which is totally true.

The good answer is that although biographical research is work, it is never hard if you’ve chosen your subject wisely. The test comes after the first year or two. Are you still intrigued? Do you still have the fever that set you off in the first place? I’ve been lucky (so far) that the answer has been yes. So the work is enjoyable and in no way “hard.”

The boring answer is that the hard part is organizing the material. How do you keep track of everything? There are ways, things you learn from others and things you invent for yourself. For Rachel Carson, I ended up with 100 pages of single-spaced notes and more than 3,000 documents on microfilm, plus a medium-sized library of books. Knowing where to find the one fact that you need from somewhere in all of that is the art of biography. Being clever helps, but sometimes it’s a matter of brute force. I can keep track of an amazing amount of stuff in my head.

You asked only about the research, not the writing. Now the writing—that is hard. I love it, but it is difficult. I had an editor once who liked to say that good writing is simple—but not easy. So true. Good writing involves several processes, but the most important is taking out the words that don’t belong. John Steinbeck knew this. In a well-known letter to his son Thom he apologized for going on for 18 pages. “I’d have written you a note,” he said, “but I didn’t have time.”

WR: John Steinbeck comes into your Rachel Carson book because of Ed Ricketts. How did Ricketts’s story contribute to your understanding of Rachel Carson?

WS: Ricketts and Carson were opposites—except in the way they looked at the ecology of the seashore. Ricketts invented himself, devised a personal philosophy that corresponded to his bohemian tastes and voracious appetites. Ricketts devoured life. Carson was the product of university training and the studious contemplation of scientific research. She lived quietly with her mother and a couple of cats. Both Ricketts and Carson died young. Carson succumbed to cancer. Ricketts was run over by a train. Had the two of them ever met face-to-face I think it might have opened a worm-hole in the universe. But they agreed utterly on the nature of the world they inhabited so differently. Each understood that every living creature is part of an ecosystem that is maintained collectively by every entity within. When Carson began work on The Edge of the Sea, which had started out as only a guidebook for beachcombers, she consciously modeled it on Ricketts’s Between Pacific Tides

WR: When did you decide to write a new John Steinbeck biography, and why?

WS: I didn’t find Steinbeck. He found me. And, as you suggest, it happened when I was researching Ed Ricketts for the Carson book, especially the collecting trip Ricketts and Steinbeck undertook to the Sea of Cortez.

This is how it begins: You come across a name you know a few things about—he was from California, he wrote The Grapes of Wrath—and you get curious. And because you’re always on the lookout for your next subject you are always trying to fit the pieces of someone’s life into a narrative. And in Steinbeck’s case it was easy. His story cuts right across the headlong march of 20th century American history, which I find fascinating. Steinbeck is born just after the close of the Victorian era—and he dies a few months before Neil Armstrong steps onto the moon. So that was his material. I was hooked.

WR: What other similarities, differences, or patterns attracted you to Audubon, Carson, and Steinbeck as subjects?

WS: Writers and artists don’t have to be writers and artists. But they feel compelled. It’s in the nature of a calling, a feeling that you’re meant to do something particular with your time on earth. I don’t mean that in any religious sense. No greater being taps you on the shoulder and makes you understand that you should write East of Eden. It’s more like you can’t help yourself. I think that’s the common trait among Audubon, Carson, and Steinbeck. They couldn’t help themselves. They became stories worth telling.

WR: How does researching Steinbeck’s life differ from your research on Carson and Audubon?

WS: I don’t know yet. There will be many similarities. All three were prolific correspondents, and letters are a biographer’s most important resource. I guess the main difference will be contextual, in exploring the history more closely with Steinbeck. I know what I want to get into my book. It’s a specific feeling that is hard to describe. There is a government retreat in Shepherdstown, West Virginia called the National Conservation Training Center. It belongs to the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service, Rachel Carson’s old outfit. It’s a beautiful campus in the rolling hills not too far from Harper’s Ferry. All of the buildings are lined with big, black-and-white photos, many from the agency’s glory days in the 1940s and 50s, of FWS personnel in the field. I’ve visited this place twice, and both times those photos got to me—elicited an ache. Like I could feel a connection to something that happened decades ago that would have been a great story to be part of. That’s the feeling you strive for in biography, the feeling that you are close to an earlier time, a different place, a person who lived in that time and place.

When I was in Scotland working on Audubon, I noticed that the library at the University of Edinburgh had a map room. I asked them if they had a map of the city from 1826, the year Audubon was there. And they did—a postal carrier’s map that was small and portable. I had them make a photocopy—I’d never been to Edinburgh—and then used that map to navigate around the city while I was there. And because Edinburgh is old, the map was still quite accurate. It helped me to see the city as Audubon saw it—to feel closer to my subject. One fog-bound night as I walked back to my hotel along one of the ancient cobbled streets I heard footsteps approaching and for a minute I let myself think it might be him.

WR: What is your research plan for the John Steinbeck biography, and how can readers of SteinbeckNow.com help?

WS: I’m just starting. There are important collections at Stanford, San Jose State, and in Salinas, as well as other places. And there are many Steinbeck experts and scholars I hope to talk with, and places he lived or that were important to him that I plan to visit. I expect to spend most of the next two years on research, and will write the book the year after that. It’s due to the publisher in the spring of 2018 and will be out sometime in 2019.

I’m happy to hear from anyone in the far-flung Steinbeck community with tips or leads about things I need to know.

Hookers With Hearts of Gold: John Steinbeck’s Prostitutes

John Steinbeck’s split-screen picture of women—Mother Virgin vs. Vestibule Whore—continues to trouble contemporary readers of East of Eden and his Cannery Row fiction. Male characters like Doc, Lee, and Sam Hamilton are complex . . . intelligent men, like Steinbeck, with mixed moral motives. Dora, Suzy, and Cathy, all prostitutes of one type or another, also show a range of feeling and behavior, but far narrower. Steinbeck’s depiction of whores almost seems bipoloar, flat and forced and, the case of Cathy, not completely convincing. Was Steinbeck, with the shining exception of Ma Joad, a male chauvinist whose writing failed to understand or value women equally with men? Reading East of Eden and Steinbeck’s Cannery Row novels in the context of Steinbeck’s contempt for conventional morality suggests that he was far from it.

Was Steinbeck, with the shining exception of Ma Joad, a male chauvinist whose writing failed to understand or value women equally with men?

John Steinbeck was, in fact, atypical of his gender and time in reversing the status of “churchy” mother-wives and the “ladies of the night” with hearts of gold who were their moral superior from Steinbeck’s point of view. In Steinbeck’s Cannery Row books, “nice women” are gossipy, negative Nancies living lives of hypocrisy, while the “working girls” offering sexual services to husbands and single men are positive, contributing members of society who display compassion and honesty without shame. Cathy, the sociopathic madam in East of Eden, is the exception who proves the rule.

In Steinbeck’s Cannery Row books, ‘nice women’ are gossipy, negative Nancies living lives of hypocrisy, while the ‘working girls’ offering sexual services to husbands and single men are positive.

But this begs a nagging question: Is it sexist to sort women into dramatically opposed categories of character, behavior, and moral worth, however heavily weighed in favor of whores? From a feminist point of view, probably so. In the context of Steinbeck’s age, however, the writer’s inversion of current values was both radical and, by today’s standards, agreeably accepting. Depicting prostitutes as positive role models was intended to shock Steinbeck’s readers, and did. But even from the perspective of modern feminism, his portrayal of their status was ahead of its time. Steinbeck’s Cannery Row whores and East of Eden prostitutes were, exceptions noted, more financially secure and less dependent on men than the wives and mothers whose husbands and son used their services.

In the context of Steinbeck’s age, his inversion of current values was both radical and, by today’s standards, agreeably accepting. Even from the perspective of modern feminism, his portrayal of women’s status was ahead of its time.

Steinbeck’s upside-down vision was no doubt rooted in his upbringing by a repressed, retiring father and a strong-minded mother with social ambitions in a small frontier town. To his way of thinking, the moral framework and sentiments about sex he learned at home and in Sunday School lacked logic and, worse, justification in the natural scheme of things. To Steinbeck, the worst aspect of Salinas culture was its hypocrisy, especially with regard to sex, but also money. Salinas hypocrites of both kinds (often the same people) populate his fiction, particularly East of Eden, one reason the novel still feels so fresh to contemporary readers.

To his way of thinking, the moral framework and sentiments about sex he learned at home and in Sunday School lacked logic and, worse, justification in the natural scheme of things.

The inspiration for Steinbeck’s characters wasn’t limited to Salinas. His Cannery Row prostitutes—notably Dora, the madam with a heart of gold—were based on real-life figures from nearby Monterey, a place he much preferred to the town where he grew up. In Sweet Thursday, a Christian Science official arrives on Cannery Row to check on a group of female Christian Science followers who, to his dismay, he learns are working for Dora, the heart-of-gold madam of a popular brothel. The idea for this over-the-top incident originated in Steinbeck’s experience, decades earlier, as a struggling writer in New York City. During his time there he dated a chorus girl and met her chorine friends, many of whom belonged to a large Christian Science church, probably the one led in the 1920s by a charismatic female Christian Science practitioner with a prosperous following.

A Christian Science official arrives on Cannery Row to check on a group of female Christian Science followers who, to his dismay, he learns are working for Dora, the heart-of-gold madam of a popular brothel.

But what of Cathy, the murderous madam in East of Eden? Christian Science was farthest thing from her deeply disturbed mind. Steinbeck biographers have suggested that Cathy’s inspiration was Steinbeck’s second wife, though that’s less important to this discussion than the profile Steinbeck creates of a heartless character—irrespective of gender—born bad. Cathy isn’t condemned because she’s a whore who refuses to remain with her husband and babies. Clearly, she was never the parenting type (nor, for that matter, was John Steinbeck). Her sin isn’t whoring; it’s monstrous, premeditated murder. Exploiting the affections of the kindhearted madam who takes her in after she abandons her home, Cathy poisons her heart-of-gold host and takes over her business, running a notorious house where anything sexual goes . . . for a price. Blackmail is on her mind, too, and her desire to expose the town’s hypocritical citizens seems somehow justified and strangely satisfying, despite her dark motives.

But what of Cathy, the murderous madam in East of Eden? Christian Science was farthest thing from her deeply disturbed mind.

And yet . . . Despite Steinbeck’s ironic moral inversion of virgin and whore, can the prostitutes who populate his fiction still be seen as stereotypes? The answer has to be a qualified yes, and it tends to blunt the impact of Steinbeck’s blow against hypocrisy for readers today. Yet he took his small town “working girls” seriously, and they got him into trouble, even among certain sophisticates in his high-flying circle of New York colleagues and collaborators. Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, the musical team that based the Broadway musical Pipe Dream on the Cannery Row characters from Sweet Thursday, turned Steinbeck’s heart-of-gold heroine Suzy, who worked at Dora’s and fell in love with Doc, into what Steinbeck bitterly described as a less-than-believable “visiting nurse.”

Steinbeck took his small town ‘working girls’ seriously, and they got him into trouble, even among sophisticates in his high-flying circle of New York colleagues and collaborators.

Because he was serious, I prefer to give John Steinbeck the benefit of the doubt on the subject of prostitutes. It’s important to remember that his “whore with a heart of gold” characters like Dora and Suzy are a literary trope with a moral purpose, social stereotypes notwithstanding. In Cannery Row, Sweet Thursday, and (Cathy excepted) East of Eden, they represent a courageous reversal of conventional values that no doubt would have offended Steinbeck’s mother, had she lived, while probably pleasing his father, who died shortly before Steinbeck’s first book success. That was in the 1930s, back in small town Salinas. But did sophisticated New York in the 1950s react that differently? Even Rodgers and Hammerstein, the kings of Broadway musical theater, choked on Steinbeck’s whores when they staged Cannery Row and failed, or so Steinbeck felt, as a result.

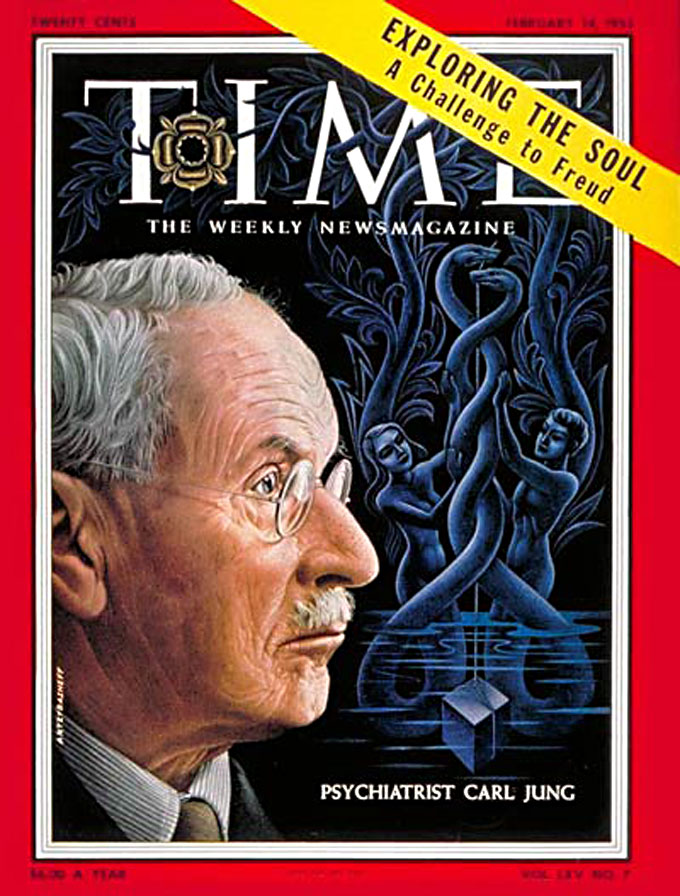

Carl Jung’s Psychology and John Steinbeck’s Horoscope

If you keep an open mind about astrology, as I’ve done in my investigation and application of its principles, you can learn quite a bit about John Steinbeck from his horoscope wheel. I know: reading astrology charts seems unusual for an electronic technician like me. Frankly, I was skeptical about the subject when I started—until I read the works Carl Jung and followers of the pioneering Swiss psychologist who fell out with his former mentor, Sigmund Freud. Steinbeck, who distinctly disliked Freud’s ideas about human sexuality and neurosis, was deeply attracted to Jung’s insights into human consciousness and imagination. Jung’s influence on Steinbeck is particularly compelling in Sea of Cortez, the record of Steinbeck’s expedition to Baja, California with Ed Ricketts 75 years ago.

John Steinbeck, who distinctly disliked Sigmund Freud’s ideas about human sexuality and neurosis, was deeply attracted to Carl Jung’s insights into human consciousness and imagination.

Steinbeck may have encountered Jung’s writing as early as 1922 while a student at Stanford, where he read philosophy and psychology along with other subjects that appealed to his needs as a writer. By the time he met Ed Ricketts and Joseph Campbell 10 years later, Jung had attracted the attention of these important figures in Steinbeck’s life as well. Sea of Cortez, written with Ricketts in 1941, bursts with Jungian ideas—such as the closely related concepts of synchronicity, acausality, and non-teleology—that get almost as much space as the ecology of the marine invertebrates and the culture of the people that Ricketts and Steinbeck observed along the way.

Carl Jung, Synchronicity, and Astrology Charts

I began my study of Carl Jung in 1965 and, three years later, astrology as part of a college assignment in which I intended to disprove astrology’s scientific validity. In my profession as an electronic technician at RCA’s Astro Electronic Division, I investigated further, mostly out of curiosity, but also out of respect for Jung’s rigorous empiricism. As a physician trained in the German tradition, he insisted on assembling evidence before expounding theory when he wrote about the personality, the unconscious, and the possibility that astrology had scientific value after all.

Jung insisted on assembling evidence before expounding theory when he wrote about the personality, the unconscious, and the possibility that astrology had scientific value after all.

I was three years into my study of Jung when I read “Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle,” where he endorses astrology as a tool in treating psychiatric patients. To be honest, the notion angered me so much I stopped reading his work until I renewed my research on astrology in an attempt to demonstrate, scientifically, why it really wasn’t worth the time. My method was simple: do as many horoscope readings as possible, then compare astrology chart results with what I learned from interviewing the individuals I had charted. I did dozens of charts and interviews and found much to discount and dismiss. But I also turned up evidence that, to my surprise, supported Jung’s claims about astrology.

I did dozens of charts and interviews and found much to discount and dismiss. But I also turned up evidence that, to my surprise, supported Jung’s claims about astrology.

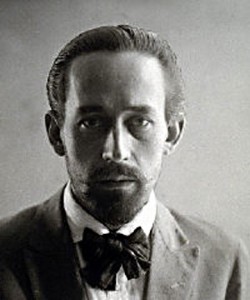

During the same period I encountered the works of Dane Rudhyar, a long-lived and multi-talented follower of Carl Jung, born in Paris, who composed modernist music, practiced a form of humanistic astrology, and died in San Francisco in 1985. Discovering Rudhyar was a watershed moment in my study of Jung and astrology, and Rudhyar’s writing still influences me in my thinking and practice today. By reading Rudhyar, Marc Edmund Jones, and other writers on the subject, I learned about the influence of the astrological signs, the planets and houses, and what astrologists call angular relationships in our lives.

During the same period I encountered the works of Dane Rudhyar, a long-lived and multi-talented follower of Carl Jung, born in Paris, who composed modernist music, practiced a form of humanistic astrology, and died in San Francisco in 1985. Discovering Rudhyar was a watershed moment in my study of Jung and astrology, and Rudhyar’s writing still influences me in my thinking and practice today. By reading Rudhyar, Marc Edmund Jones, and other writers on the subject, I learned about the influence of the astrological signs, the planets and houses, and what astrologists call angular relationships in our lives.

John Steinbeck, Ed Ricketts, and Sea of Cortez

I’m a practical, intuitive type, and I found interpreting chart patterns and relationships, in both their static and dynamic senses, fascinating. Probably for the same reason, I also enjoyed the fiction of John Steinbeck. What I learned from Carl Jung’s “Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche,” “Psychological Types,” and “Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle” clarified my understanding of Steinbeck and Ricketts’s holistic, non-teleological thinking in Sea of Cortez, Steinbeck’s most thoughtful work of non-fiction.

What I learned from Carl Jung’s ‘Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche,’ ‘Psychological Types,’ and ‘Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle’ clarified my understanding of Steinbeck and Ricketts’s holistic, non-teleological thinking in ‘Sea of Cortez.’

As I read astrology charts and applied what I was learning, Ricketts and Steinbeck’s perceptions helped hone my technique and increase my skill. In my business, I was discovering the truth of Carl Jung’s belief that “Astrology is assured of recognition from psychology without further restrictions,” that it “represents the summation of all the psychological knowledge of antiquity.” Jung explained why he believed this was so: “The fact that it is possible to construct a person’s characters from the data of his nativity shows the validity of astrology. I have often found that in cases of difficult psychological diagnosis, astrological data elucidated points which I otherwise would have been unable to understand.” Astrology, said Jung, could be shown empirically to be scientific, “a large-scale example of synchronicity if it had at its disposal thoroughly tested findings.”

What John Steinbeck’s Astrological Chart Reveals

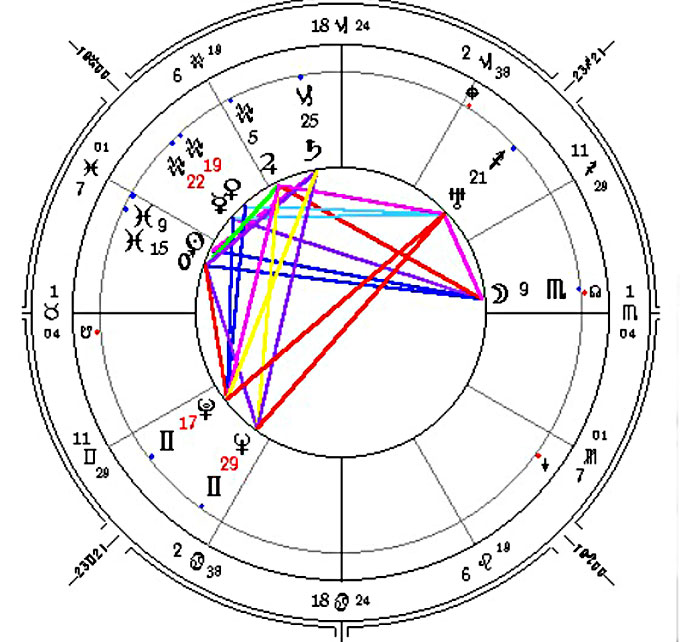

What can we learn from interpreting John Steinbeck’s astrological wheel chart, shown here?

To start with, the most influential part of anyone’s horoscope chart is the Sun, the key element in life. For example, when we say we’re a Virgo, Leo, or Aquarius, we mean that the Sun was in that particular astrological sign or constellation at the moment of our birth. Based on the location of the Sun sign when John Steinbeck—a Pisces—was born, it’s clear that Steinbeck was an Introverted Sensation Type with a Thinking auxiliary in his psychological make-up. Sensation as the primary function naturally made him more perceptive than judgmental—a helpful profile for the non-teleological exploration of human behavior demonstrated in Sea of Cortez and in his fiction.

Sensation as the primary function naturally made Steinbeck more perceptive than judgmental—a helpful profile for the non-teleological exploration of human behavior demonstrated in ‘Sea of Cortez’ and in his fiction.

Practically speaking, this means that when Steinbeck considered a situation, all the information he gathered through observation and experience went from the source—what he actually sensed—into his imaginative unconscious. There it was shaped and modified by his fears, hopes, desires, and prejudices before becoming conscious in his mind or relating to his emerging Ego.

When Steinbeck considered a situation, all the information he gathered through observation and experience went from the source—what he actually sensed—into his imaginative unconscious.

As Steinbeck and Ricketts suggest in the long philosophical passages that make Sea of Cortez fascinating to readers like me (and perplexing to others), one goal of what they call non-teleological thinking is to reduce the unconscious influence and stick as closely as possible to the reality of the object being perceived. In this connection, introverts rely on internal, subjective, and experienced evidence, seeing the world in themselves. Extraverts, by contrast, judge their perceptions based upon external evidence, seeing themselves in the world. Though it’s a bit of an over-simplification, it seems fair to say that John Steinbeck was an introvert with extraordinarily acute perception about human character and behavior.

As Steinbeck and Ricketts suggest in the long philosophical passages that make Sea of Cortez fascinating to readers like me (and perplexing to others), one goal of what they call non-teleological thinking is to reduce the unconscious influence and stick as closely as possible to the reality of the object being perceived. In this connection, introverts rely on internal, subjective, and experienced evidence, seeing the world in themselves. Extraverts, by contrast, judge their perceptions based upon external evidence, seeing themselves in the world. Though it’s a bit of an over-simplification, it seems fair to say that John Steinbeck was an introvert with extraordinarily acute perception about human character and behavior.

Though it’s a bit of an over-simplification, it seems fair to say that John Steinbeck was an introvert with extraordinarily acute perception about human character and behavior.

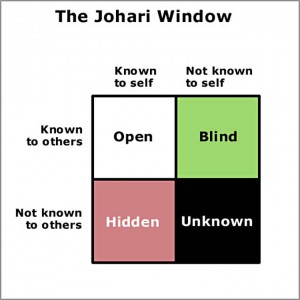

In the humanistic astrology of Dane Rudhyar and others, the Sun’s location in an individual’s astrology chart reveals the Self, the Soul, at the center of the psyche. This Self can be described as having three major components in the terminology developed by Carl Jung: the personality or persona, the Ego, and the Unconscious. Using the Johari Window, we can visualize these three components. The persona is represented by the “Open” and “Blind” panes. The “Blind” pane signifies the parts of our Ego that others see in us but about which we are unaware. The “Hidden” window includes those parts of our Ego that we recognize but do not wish them to see. In a horoscope wheel chart, the Sign and Degree of the cusp of the First House (the line between the 12th House and the 1st House, usually at nine o’clock) represents the way an individual projects to or is perceived by others: his or her “persona.”

In the humanistic astrology of Dane Rudhyar and others, the Sun’s location in an individual’s astrology chart reveals the Self, the Soul, at the center of the psyche. This Self can be described as having three major components in the terminology developed by Carl Jung: the personality or persona, the Ego, and the Unconscious. Using the Johari Window, we can visualize these three components. The persona is represented by the “Open” and “Blind” panes. The “Blind” pane signifies the parts of our Ego that others see in us but about which we are unaware. The “Hidden” window includes those parts of our Ego that we recognize but do not wish them to see. In a horoscope wheel chart, the Sign and Degree of the cusp of the First House (the line between the 12th House and the 1st House, usually at nine o’clock) represents the way an individual projects to or is perceived by others: his or her “persona.”

In a horoscope wheel chart, the Sign and Degree of the cusp of the First House represents the way an individual projects to or is perceived by others: his or her ‘persona.’

All this suggests that how a person projects himself or herself may mask the real individual, often quite dramatically. So it’s important to remember that we are partially—sometimes significantly—responsible for the opinions others have about us: we unconsciously project our own qualities into the perceptual image those around us, coloring and frequently complicating our relationships. The influence of the Sun may be masked within the persona, and often we are responsible for the mask. Consider Carl Jung’s archetypal concept of Shadow, for instance. In Jungian terms, our life experiences provide growth lessons along a path between the image we project, our Ego, and who we actually are as defined by the sign degree of our Sun.

In Jungian terms, our life experiences provide growth lessons along a path between the image we project, our Ego, and who we actually are as defined by the sign degree of our Sun.

Humanistic astrologers recognize this truth: our journey through life includes challenges that cause the persona as defined by the qualities represented in our Ascendant to join the Ego and more closely align with the Sun or Self. As Jung suggests when discussing the Shadow, this makes the journey especially difficult when it challenges the perceptions of those closest to us and can create interpersonal problems with perfect strangers. These were issues for John Steinbeck throughout his life.

As Jung suggests when discussing the Shadow, this can create interpersonal problems with perfect strangers. These were issues for John Steinbeck throughout his life.

Steinbeck’s Ascendant is at 1 degree 4 minutes Taurus, significant because it increased the likelihood of his compatibility with Ed Ricketts, who had a Taurus Sun. Given what I’ve learned about Taurus Ascendants, I suspect that Steinbeck, with a Pisces Sun, was sometimes judged by others to be more predictable than he really was. On first meeting, his personality would have attracted someone like his wife Carol, who also had a Pisces Sun. A woman of her perceptiveness would have tacitly understood her need for a partner with stability, and when they met Steinbeck’s persona could have been mistaken for that of a Taurus. Steinbeck, with a Taurus Ascendant, would offer such an illusion.

Steinbeck’s Taurus Ascendant is significant because it increased the likelihood of his compatibility with Ed Ricketts, who had a Taurus Sun.

Most importantly, John Steinbeck’s horoscope wheel reveals a significant pattern formed by the location of planets in Sign and Houses. The majority of planets in his astrology chart are in the upper left quarter, an area that is associated with objective social types. Steinbeck’s avowed goal as a writer was social: to observe others, increase understanding, and influence change—a purpose that history has proven he met beyond anyone’s expectations, including his own. For readers today, this may be the most important lesson to be learned from John Steinbeck’s astrology chart, his understanding of Carl Jung, and his collaboration with Ed Ricketts in writing Sea of Cortez, a gift from the tide pool and the stars.

The author welcomes inquiries at wstillwagon1@earthlink.net.—Ed.

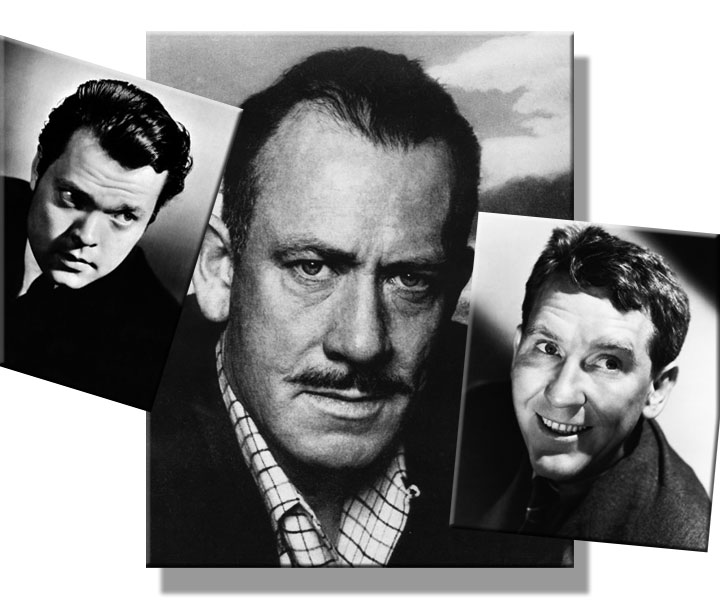

Orson Welles at 100: How Would a Meeting Between John Steinbeck and the Creator of Citizen Kane Go?

The legendary American actor-writer-director Orson Welles was born 100 years ago today. That’s as good a reason as any to contemplate how a meeting might have gone between the controversial creator of Citizen Kane and the author of The Grapes of Wrath. Despite different backgrounds, opposite personalities, and divergent careers, John Steinbeck and Orson Welles shared much, including progressive politics, Hollywood troubles, and rocky friendships with the actor Burgess Meredith. It’s hard to imagine their paths never crossed and amusing to consider what they talked about if they had the chance. Opposites attract, particularly when there’s a common enemy like William Randolph Hearst.

Orson Welles was born 100 years ago today. That’s as good a reason as any to contemplate a meeting between the controversial creator of Citizen Kane and the author of The Grapes of Wrath.

Steinbeck’s 1939 novel and Welles’s 1941 film both caused serious problems for their creators, arousing public opinion against powerful interests and incurring the wrath of powerful men like Hearst, the California media mogul portrayed by Welles in Citizen Kane. Burgess Meredith, the puckish actor who played George in the 1938 film Of Mice and Men, was a member of Welles’s theater company in New York and became a close friend of Welles and Steinbeck as a result of artistic collaboration. It’s possible Meredith suggested that Welles read Steinbeck’s short story “With Your Wings,” written (perhaps at Meredith’s urging) for radio broadcast in the 1940s.

Steinbeck’s 1939 novel and Welles’s 1941 film caused serious problems for their creators, arousing public opinion and incurring the wrath of men like William Randolph Hearst.

For years John Steinbeck, Orson Welles, and Burgess Meredith moved in New York and Hollywood entertainment circles dominated by parties, personalities, and adultery-and-divorce gossip (all three had multiple wives). In later life, Welles and Steinbeck fell out with Meredith, though for different reasons. Until that happened, however, both writers were close to Meredith, whose sunny side attracted moody men like Steinbeck and Welles. Movies and politics, fame and fortune, Meredith and Hearst: Orson Welles and John Steinbeck, lubricated and relaxed if chemistry clicked, would have plenty to talk about over drinks or at a party.

John Steinbeck, Orson Welles, and Biography

Robert DeMott, an enterprising scholar who thinks creatively along these lines, piqued my curiosity about a possible connection by suggesting that Burgess Meredith could have been Welles’s conduit for the radio broadcast of “With Your Wings.” In response to my question about the cloudy origin of Steinbeck’s story, Bob said Meredith knew both men well and was a member of the theater company that performed Welles’s sensational production of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, set in Haiti and staged in Harlem, which made headlines and caught the attention of the Hollywood film establishment. History moved fast from there.

Meredith was a member of the theater company that performed Welles’s version of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, set in Haiti and staged in Harlem, which made national headlines and caught Hollywood’s attention.

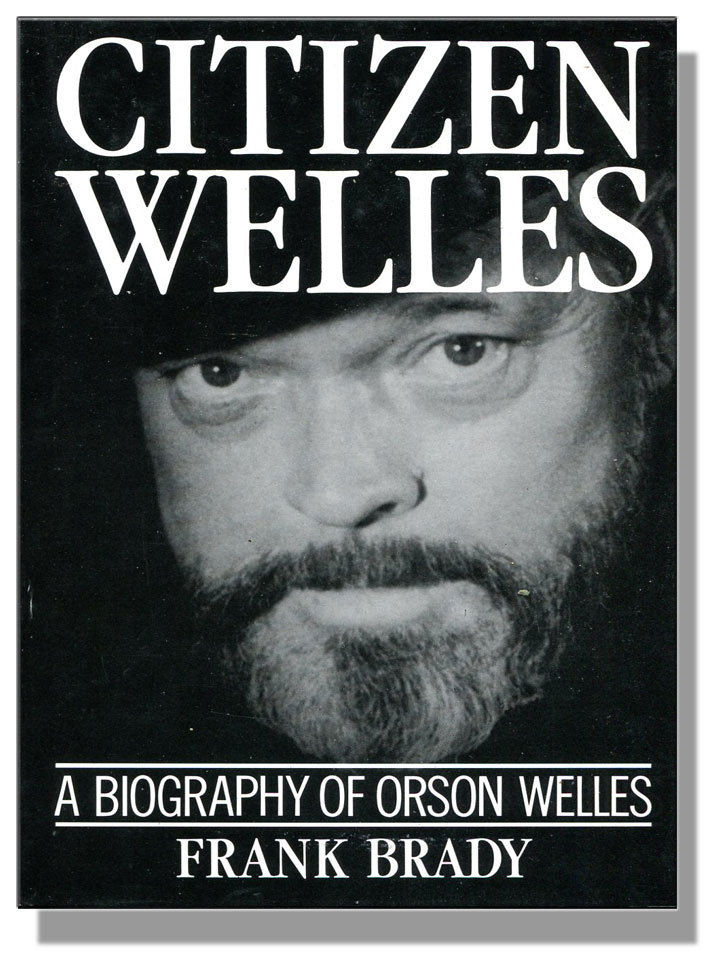

Meredith’s memoir, published 60 years later, recalls the excitement surrounding the production and relates incidents in the actor’s fraught friendships with Welles and Steinbeck. Unfortunately, So Far, So Good is weak on details and reveals nothing about Welles and Steinbeck having met. Nor does Frank Brady’s Citizen Welles, a film-focused account of Welles’s rapid rise and fall following the notoriety of Citizen Kane. But Brady’s perceptive portrait of a precocious, tormented genius suggests why Welles’s view of celebrity differed dramatically from Steinbeck’s, despite shared experience of publicized dalliances and divorces, film-studio mistreatment, and persecution by opponents in government and press.

Welles’s view of celebrity differed dramatically from Steinbeck’s, despite shared experience of publicized dalliances and divorces, film-studio mistreatment, and persecution by opponents in government and press.

Both men were autodidacts who read insatiably and relished the sound of words from an early age. Unlike Steinbeck, Welles was also an extroverted autocrat with an ability to project his voice, promote his talent, and write very quickly. Ireland was important to each, but for reasons that underscored their contrasting characters and careers. Welles, an ambitious Midwesterner, started acting on the Irish stage at 18. Steinbeck, a late-blooming Californian with Irish grandparents, visited Ireland only once, late in life, and was disappointed when he did. As New Deal Democrats, both produced patriotic propaganda for the U.S. war effort, Steinbeck in print and Welles on air. Each attracted the attention of the FBI anyway.

Unlike Steinbeck, Welles was also an extroverted autocrat with the ability to project his voice, promote his talent, and write very quickly.

They hated William Randolph Hearst, the powerful publisher who created yellow journalism and built the crazy castle caricatured, along with Hearst’s actress-lover Marion Davies, in Citizen Kane. As Brady’s biography demonstrates, Welles never really recovered from the aftermath of his attack on Hearst. The monied interests skewered by Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath were almost as hurtful, at least at first, but Steinbeck’s career didn’t suffer permanent damage, despite a dry spell during the 1940s when he churned out stories and scripts mangled by studio rewrite-men and directors. He never forgave Alfred Hitchcock for the racial stereotyping and sentimentality the English director inserted into Steinbeck’s World War II movie Lifeboat.

Welles never really recovered from the aftermath of his attack on Hearst. The monied interests skewered in The Grapes of Wrath were almost as hurtful to Steinbeck, who survived the dry spell that followed.

Hitchcock was a likely topic of any conversation Steinbeck had with Welles, whose obsessive anxiety about other directors’ treatment of his ideas shadowed him until he died. John Huston’s name probably came up as well. Both men were guests at Huston’s estate in Scotland, though Steinbeck’s enjoyment of the genial Irish director’s hospitality was free from the competitiveness that characterized Welles’s relations with most movie people. Henry Fonda read poetry at Steinbeck’s well-attended funeral in 1968. Welles’s death in 1985 attracted less devoted attention.

Hitchcock was a likely topic of any conversation Steinbeck had with Welles, whose obsessive anxiety about other directors’ treatment of his ideas shadowed him until he died.

Welles and Steinbeck also enjoyed the hospitality of Burgess Meredith, whose country place not far from Manhattan was a convenient getaway for exhausted celebrities and uninhibited conversation. Steinbeck and Welles experienced Broadway fatigue at about the same time (Steinbeck with Pipe Dream and Burning Bright). Both loved music and liked to head downtown to hear jazz and to drink, the two great social equalizers of their period in New York. Eddie Condon’s jazz club in the Village is another appealing venue for an imagined conversation between the two men, perhaps about how badly it hurt to fail on Broadway while others were succeeding.

Henry Fonda, Burgess Meredith, and Memory

Like Burgess Meredith, Henry Fonda offers little of substance about Welles or Steinbeck in Fonda: My Life. But when asked for an opinion about a Steinbeck-Welles connection, Steinbeck’s biographer Jay Parini said it was safe to assume Steinbeck and Welles not only met but probably got along: “I’d be amazed if they didn’t meet, and I’d be very amazed if they didn’t find something to like in each other.” Responding to the same question for this blog post, another expert source quoted a conversation that occurred between Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, the actor-director who worked hard to restore Welles’s reputation. Ironically, the quoted conversation confirms that—unlike Henry Fonda—Orson Welles actually read The Grapes of Wrath:

WELLES: I hated [John Ford’s film adaptation of The Grapes of Wrath].

BOGDANOVICH: Well, it’s better than the book.

WELLES: Oh no, the book is much better.

BOGDANOVICH: Really?

WELLES: At the time I saw The Grapes of Wrath, if you told me I’d ever have a good word to say for Ford again . . . I hated him so. I would have hit him if I’d seen him afterwards. He made a movie about mother love. You know, a sentimental, stupid, sloppy movie. Beautifully photographed, and all the beautiful photography was done by a 2nd unit cameraman without Ford or Toland, as I found out. I complimented Toland on those great shots of those things, and he said, “I didn’t make it. I didn’t do it, and Jack Ford wasn’t there either.”

BOGDANOVICH: I didn’t know that.

WELLES: And all that stuff they did with that awful actress that everybody loves, Jane Darwell, that awful Jane Darwell, and all those terrible creeps walking around being cute. God, I hated that picture!

Welles’s dim view of John Ford’s adaptation of The Grapes of Wrath sounded pitch-perfect when I read it, and it led me to Henry Fonda, whose role as Tom Joad launched Fonda’s career and friendship with John Steinbeck. Steinbeck’s name comes up frequently in Fonda’s memoir, which includes details about Steinbeck’s funeral that differ from Steinbeck biographies. But Fonda’s version of the phone call he got from his agent about the casting of The Grapes of Wrath struck me as oddly off-key:

It was a joyous moment [for Fonda] when Leland Hayward telephoned . . .

“Ever hear of The Grapes of Wrath?” the agent asked.

“Sure have,” Fonda answered readily. “It’s about the farmers who were driven out of Oklahoma by the dust storms and made their way to California . . . “

“I didn’t ask you for a book report,” Hayward said, stopping the enthusiastic actor. “I just want you to know Zanuck bought it for Fox.”

I was intrigued by a recent remark from Richard Astro, an American scholar of prodigious memory, that Fonda admitted he never read The Grapes of Wrath when interviewed for Dick’s groundbreaking study of John Steinbeck. Clearly, Welles not only read Steinbeck’s book but understood the author’s deep meaning—another tempting topic of imagined conversation between the two men, along with the mystery of “Rosebud” in Citizen Kane. Like Welles, Steinbeck was misunderstood, even by friends such as Fonda, and he suffered for his art. Not long before he died he advised a struggling writer, “Your only weapon is your work.” Welles had every reason to agree.

My source for the Welles-Bogdanovich exchange added the following tidbit from an era when actors like Burgess Meredith and Henry Fonda were attacked for being liberals and writers like Orson Welles and John Steinbeck were accused of being socialists or worse: “It’s interesting that Ayn Rand, in one of her private letters, lumped John Steinbeck and Orson Welles together as ‘Marxist propagandists.’” As a non-admirer of Ayn Rand, I consider her unintended tribute to Steinbeck and Welles, even if the pair never met, cause for celebration. Happy birthday, Orson. Unlike us, Citizen Kane will never die.

My source for the Welles-Bogdanovich exchange added the following tidbit from an era when actors like Burgess Meredith and Henry Fonda were attacked for being liberals and writers like Orson Welles and John Steinbeck were accused of being socialists or worse: “It’s interesting that Ayn Rand, in one of her private letters, lumped John Steinbeck and Orson Welles together as ‘Marxist propagandists.’” As a non-admirer of Ayn Rand, I consider her unintended tribute to Steinbeck and Welles, even if the pair never met, cause for celebration. Happy birthday, Orson. Unlike us, Citizen Kane will never die.

Cannery Row Symposium Celebrates Ed Ricketts, John Steinbeck’s Prince of Tides

John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts’s legendary expedition from Monterey Bay to the Sea of Cortez 75 years ago was celebrated in a February 21 symposium organized by Cannery Row historian Michael Kenneth Hemp and sponsored by the not-for-profit Cannery Row Foundation. Richard Astro—an academic superstar who first identified the John Steinbeck-Ed Ricketts relationship as a reason for the enduring appeal of The Grapes of Wrath—was the opening speaker at the Pacific Grove, California event, establishing the context for a day of rediscovery, revival, and some surprising news.

The Pioneer Who Blazed the Steinbeck-Ricketts Trail

Astro, former provost and current professor at Drexel University, finished writing his doctoral dissertation on Steinbeck the day the author died in 1968. The budding scholar’s first book, John Steinbeck and Edward F. Ricketts: The Shaping of a Novelist, appeared in 1973, setting the stage for Steinbeck research that continues to this day. In a distinguished career as a university administrator and writer about American literature, Astro—along with his ebullient wife Betty—divides his time between Philadelphia and Florida. Their return to Pacific Grove after a 10-year absence was welcome, and the early-morning audience was energized by Astro’s straight talk about Steinbeck and scholarship, his signature as a public speaker.

Astro’s first book, John Steinbeck and Edward F. Ricketts: The Shaping of a Novelist, appeared in 1973, setting the stage for Steinbeck research that continues to this day.

Astro got his PhD at the University of Washington and his first teaching job at Oregon State. At the time John Steinbeck was considered a has-been by critics, but Astro has a contrarian streak and choice and chance were on his side when he selected Steinbeck as his subject. An unsolicited visit from Joel Hedgepeth, a scientific colleague of Ricketts also teaching in Oregon, led to a meeting with Ricketts’s son, Ed Jr., who gave Astro letters between Steinbeck and Ricketts that no one else had seen. The senior Ricketts died in 1948, but others who knew Steinbeck well were still alive—celebrities types like Burgess Meredith and Henry Fonda, friends from Monterey Bay days, former and current wives—and Astro interviewed each.

At the time John Steinbeck was considered a has-been by critics, but Astro has a contrarian streak and choice and chance were on his side when he selected Steinbeck as his subject.

Occasionally, as with Steinbeck’s wife Carol Henning, there were moments of psychodrama that Astro learned to manage, gaining a useful ability to separate fact from fiction about Steinbeck’s complicated life. Ed Ricketts, a Monterey Bay biologist whose name was unknown to the public at the time, kept coming up in the process. Astro borrowed Ricketts’s metaphor—“breaking-through”—in describing the excitement he felt when he discovered Ricketts’s pervasive presence in Steinbeck’s best writing, including The Grapes of Wrath. As a result Steinbeck scholarship advanced rapidly, but Astro was modest about his role: “I set the table; those who followed cooked the dinner.”

As a result Steinbeck scholarship advanced rapidly, but Astro was modest about his role: ‘I set the table; those who followed cooked the dinner.’

Ricketts and Steinbeck first met in 1930, forging an intimate friendship that survived multiple partners, married and otherwise, and provided Steinbeck material for his fiction. Occasional rivalry rocked the boat, including relations with Joseph Campbell, who broke with Steinbeck after an emotional disagreement but continued to correspond with Ricketts, who possessed a knack for being loved by everybody. With money from The Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck and Ricketts hired The Western Flyer in 1940 and explored the Gulf of California, describing the experience in a book, Sea of Cortez, published three days before Pearl Harbor.

With money from The Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck and Ricketts hired The Western Flyer in 1940 and explored the Gulf of California, describing the experience in Sea of Cortez, published three days before Pearl Harbor.

Reissued in 1995 with an indispensable introduction by Richard Astro, Sea of Cortez comprises the core of Steinbeck and Ricketts’s collaborative thinking about God, man, and nature. In his remarks, Astro noted that the spirit of Ed Ricketts is also present in The Grapes of Wrath, where Ricketts appears as the questioning preacher Jim Casy, whose thinking about belief and behavior are essential to Steinbeck’s purpose in the novel. Other artists of the era—Oklahoma novelist Sonora Babb, New Deal filmmaker Pare Lorentz—also documented the Dust Bowl and Great Depression, but Astro observed that their works quickly became period pieces while The Grapes of Wrath, underpinned by Steinbeck and Ricketts’s collaborative philosophy, “transcends time and place, as valid now as the day it was written.”

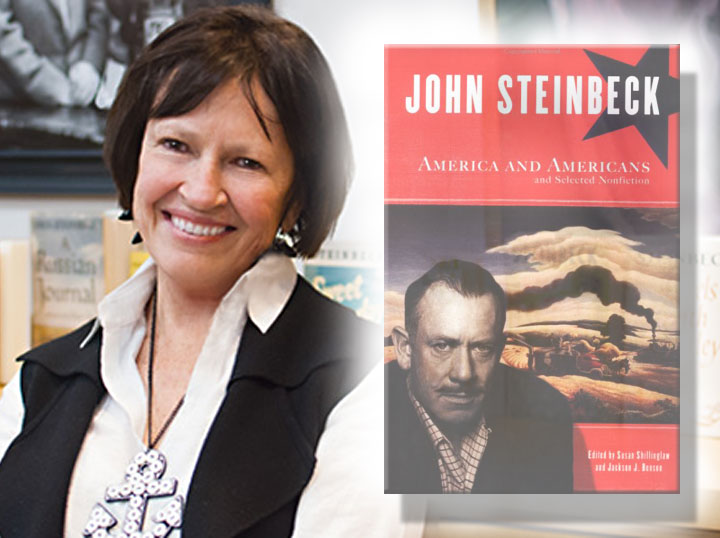

How to Avoid Drowning in Sea of Cortez Scholarship

Perhaps no star in the current constellation of Steinbeck scholars has done more to complete the table set by Richard Astro than Susan Shillinglaw, author of Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage and On Reading The Grapes of Wrath and the writer and editor of essays on Steinbeck and Ricketts’s environmentalism. A professor of English at San Jose State University who lives in the Monterey Bay area, she spoke on “Layered Fiction and Deep Ecology: John, Ed, Carol, and The Grapes of Wrath” at the conclusion of the Cannery Row symposium. Like Astro, she has a gift for expressing ideas clearly to the non-specialist audience attracted by Steinbeck’s works. (Shillinglaw met her husband, a marine biologist at Stanford University, when he was chief scientist on a 2004 voyage that recreated the Sea of Cortez trip taken by The Western Flyer.)

Like Richard Astro, Susan Shillinglaw has a gift for expressing ideas clearly to the non-specialist audience attracted by John Steinbeck’s works.

Bob Enea, a descendant of the colorful Western Flyer crew member Sparky Enea and the ship’s captain Tony Berry, recounted the rise and fall of the Monterey Bay fishing industry, describing the day Ricketts and Steinbeck left Monterey Bay for their Sea of Cortez journey after a bon-voyage party remembered as Cannery Row’s biggest bash ever. The symposium’s energetic organizer, Michael Hemp, spoke on “Cannery Row: The Industrial Stage for John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row Fiction.” Steven Federle, a John Steinbeck scholar at Solano College, discussed the provenance of Steinbeck’s libidinous short story “The Snake,” a psychological curiosity set in Ricketts’s lab on Cannery Row. Don Kohrs, librarian at Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Station, enumerated the obstacles Ricketts faced in finishing Between Pacific Tides, the textbook published by Stanford in 1939. Kohrs also described materials, including Ed Ricketts’s famous index-card file, from the collection at Hopkins, where Steinbeck took a summer course in biology several years before meeting Ed Ricketts.

A Pair of Cannery Row Films and Western Flyer News

In publicity for the symposium the Cannery Row Foundation promised variety and surprise and delivered both. Eva Lothar, a French medical doctor who created the 1973 cinematic poem Street of the Sardine, spoke about moving to the Monterey Bay area as a young widow shortly after the Cannery Row sardine supply collapsed. (Her story about filming Street of the Sardine, shown at the symposium, is the subject of an upcoming SteinbeckNow.com video special.) Monterey Bay-area filmmakers Steve and Mary Albert exhibited their impressive documentary, The Great Tide Pool, causing a viewer to say she wished Steinbeck and Ricketts were alive to see both films, one interpreting Cannery Row ecology as poetry, the other as prose.

A viewer said she wished Steinbeck and Ricketts were alive to see the pair of films, one interpreting Cannery Row ecology as poetry, the other as prose.

Two speakers not listed on the printed program provided the surprise promised before the symposium began. John and Andy Gregg, businessmen-brothers, announced that they were buying The Western Flyer to restore and return the legendary vessel to its Monterey Bay home as a permanent educational resource for students and, perhaps, visitors to Cannery Row. The Greggs operate a geophysical investigation and marine drilling business, the kind of know-how that makes success in meeting that objective seem likely. Their straight answers to cost-and-schedule questions were as impressive as their goal: to assure that the boat used by the Prince of Tides and the author of The Grapes of Wrath to explore the Sea of Cortez will survive as long as John Steinbeck, Ed Ricketts, and Monterey Bay continue to matter.

Jim Kent: Symposium a Tipping Point for Cannery Row?

A frequent Cannery Row visitor who applies Steinbeck and Ricketts’s insights in his international consulting business flew from Colorado to attend the symposium. Asked for his reaction, Jim Kent expressed delight at the event’s energy and renewed optimism about Cannery Row’s future. “Don Kohrs got us excited when we learned that he has been assembling writings and other material of Ed Ricketts owned by the Hopkins Marine Station,” he explained. “Don located Ricketts’s legendary index cards,” detailing scientific specifics of unusual marine specimens from Monterey Bay tagged by the Prince of Tides as early as 1928. “Ricketts was a thinker and Steinbeck’s friend, but he was first and foremost a scientist,” Kent noted. “This dimension has been lost in academic writing about the characters Steinbeck based on Ricketts, and it’s great to see the Ricketts revival beginning here, where it all started.”

Jim Kent, a frequent Cannery Row visitor, observed, ‘It’s great to see the Ricketts revival beginning here, where it all started.’

Kent added that the symposium marked a new phase in public appreciation of John Steinbeck, Ed Ricketts, and Cannery Row. “My understanding of Steinbeck and Ricketts’s social ecology taught me how to bypass top-down thinking in working with community groups to make changes that benefit people, not just profit,” he said. “Ed Ricketts and John Steinbeck understood the importance of gathering places, informal networks, affinity-relationships, and bottom-up change. What I heard today leaves old ways of conceiving Cannery Row, Monterey Bay, and Steinbeck studies in the dust. Steinbeck and Ricketts saw ecological collapse coming when nobody would listen. I am sure they could see this, too!”

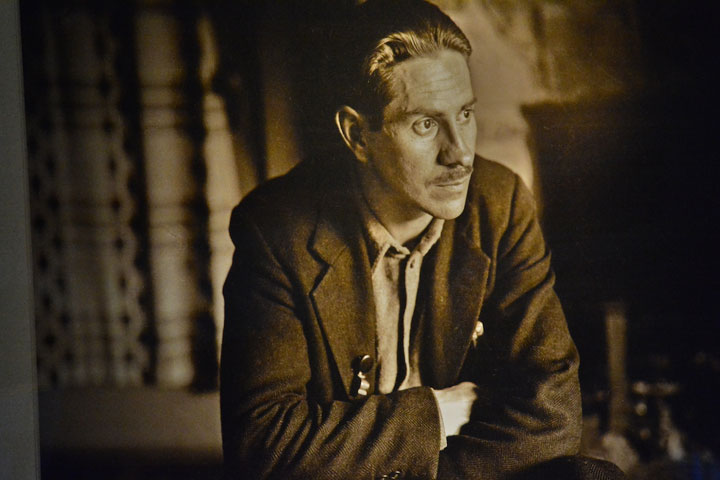

Image of Ed Ricketts from the historical photograph collection of Pat Hathaway, featured in the Winter 2015 issue of Carmel magazine.

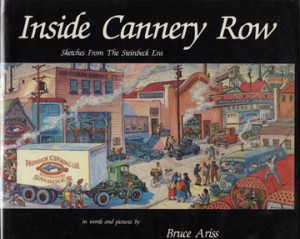

Calling Dr. Freud? Letter Explains John Steinbeck’s Short Story “The Snake”

Fresh questions raised by scholars about the source of John Steinbeck’s brief short story “With Your Wings,” recently published for the first time, reminded me that Steinbeck’s college friend, the writer A. Grove Day, once sent me a personal letter with an eye-witness explanation of the incident behind “The Snake,” an earlier short story set in Doc’s Lab on Cannery Row. “The Snake” was written before Tortilla Flat appeared in 1935, and Steinbeck’s friend Bruce Ariss, the Cannery Row painter-writer-publisher, printed it as “A Snake of One’s Own” (the original title) in a local publication called The Beacon. In 1938 the short story was published in Esquire magazine and in Steinbeck’s classic short story collection The Long Valley, where it continues to attract readers fascinated by its gritty, gruesome subject and intriguing origin.

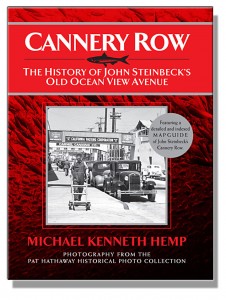

“The Snake” takes place in a familiar version of Ed Ricketts’ Doc’s Lab on Cannery Row, a frequent venue in Steinbeck’s writing and a big part of my recently revised book Cannery Row: The History of John Steinbeck’s Old Ocean Avenue . Steinbeck tells the story from the viewpoint of a Dr. Phillips, the story’s Ed Ricketts character, and it contains stark sexual symbolism frequently interpreted by critics in Freudian terms. But did the disturbing incident at the story’s core come from Steinbeck’s imagination, or did it really happen as described? Even Steinbeck’s friends from the time didn’t agree about where he got the idea for “The Snake.”

“The Snake” takes place in a familiar version of Ed Ricketts’ Doc’s Lab on Cannery Row, a frequent venue in Steinbeck’s writing and a big part of my recently revised book Cannery Row: The History of John Steinbeck’s Old Ocean Avenue . Steinbeck tells the story from the viewpoint of a Dr. Phillips, the story’s Ed Ricketts character, and it contains stark sexual symbolism frequently interpreted by critics in Freudian terms. But did the disturbing incident at the story’s core come from Steinbeck’s imagination, or did it really happen as described? Even Steinbeck’s friends from the time didn’t agree about where he got the idea for “The Snake.”

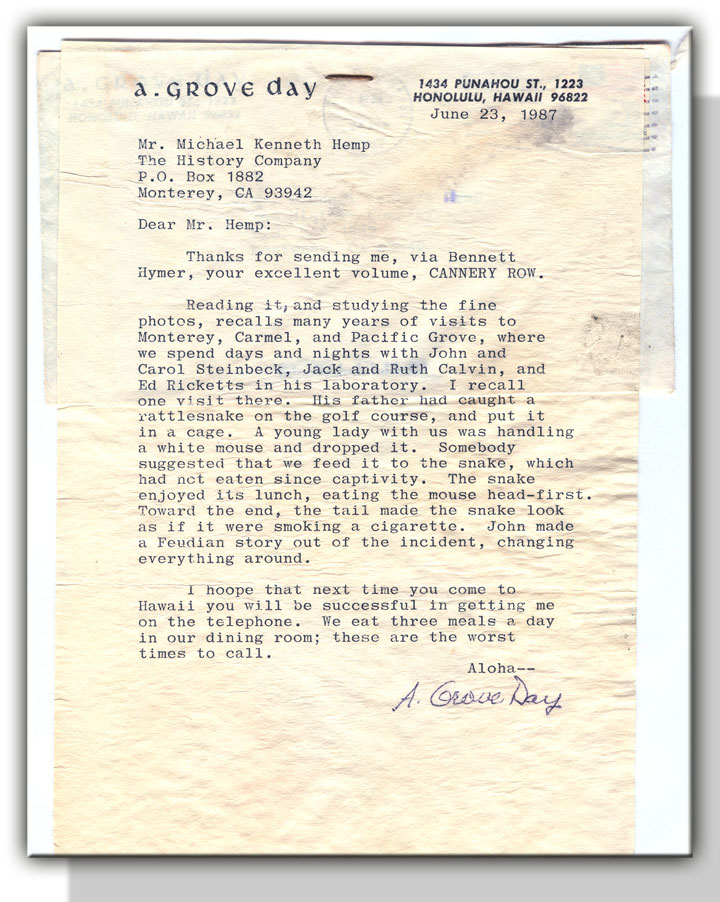

While reading comments by Robert DeMott concerning the context of John Steinbeck’s forgotten World War II story “With Your Wings,” I recalled an acknowledgement letter I received years ago from A. Grove Day, the late historian and biographer who became Steinbeck’s friend at Stanford in the 1920s, where both were members of the famous Stanford English Club. Born in Philadelphia in 1904, Grove died in Hawaii—the subject of his special expertise as a scholar—in 1994. I found his fascinating 1987 letter about “The Snake” in my files, postmarked from Honolulu.

While reading comments by Robert DeMott concerning the context of John Steinbeck’s forgotten World War II story “With Your Wings,” I recalled an acknowledgement letter I received years ago from A. Grove Day, the late historian and biographer who became Steinbeck’s friend at Stanford in the 1920s, where both were members of the famous Stanford English Club. Born in Philadelphia in 1904, Grove died in Hawaii—the subject of his special expertise as a scholar—in 1994. I found his fascinating 1987 letter about “The Snake” in my files, postmarked from Honolulu.

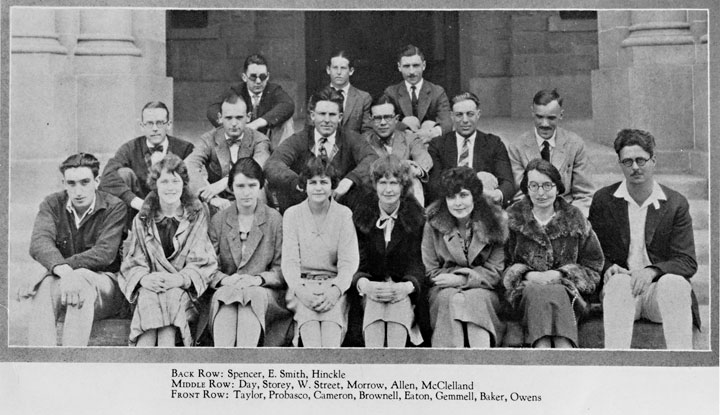

Grove’s letter, which shows his skill as a writer and his knowledge of Doc’s Lab, augments other interpretations of “The Snake,” including those by two other friends from Steinbeck’s Stanford student days, Toby Street and Dook Sheffield. (In this photo of the English Club, Day is seated far left on the middle row; Street sits third from the left on the same row.) Grove’s letter claims that Ricketts’s father—who helped out at his son’s Cannery Row marine specimen business—caught the snake on a golf course and put it in a cage at the Lab, where “a young lady with us” fed it a white mouse as the snake’s first meal in captivity. Sheffield, who became a newspaper reporter, was more direct when he spoke about the story. He claimed that a local showgirl needed the snake for her act, although a rattlesnake would be a dangerous choice for the purpose.

Street commented about “The Snake” in a 1975 interview with Martha Heasley Cox, founder of the Steinbeck Studies Center at San Jose State University. His version possesses the weight of what lawyers call credible evidence and is quoted in full below. At this point in his exchange with Professor Cox, Street mentions “a girl that was on the circuit here [who] took a fancy to Ed.” When asked by Cox to explain what he means by “the circuit” (roadhouse and bar entertainment replacing vaudeville with some burlesque), Street employed a combination of diplomacy and directness developed in his post-Stanford career as a Monterey attorney for clients including John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts. Like Grove, Street was as careful with facts as with feelings. When he spoke to his interviewer for the record about “The Snake,” he may have omitted living names, dates, and details.

“They used to have, you know, the piano player and a couple of girls and they’d entertain and they’d go around. And this girl happened to be [at the Blue Bell Café] and took a fancy to Ed, and Ed invited her to the lab. And she was a kind of sexy-looking dame and so while she was there, he said that he had to feed the snake. He had a big cage, quite a big cage full of white rats—and he went in there and selected one and put it in with the rattlesnake. The mouse ran all around, and this girl was just fascinated by the damned thing. And then, pretty soon, the little mouse stopped and the rattlesnake struck. Its fang caught in the mouse. And when he pulled, he brought the mouse back with it, and of course the mouse didn’t pay any attention, just ran around until the toxic effects began to take hold. His back got all rigid, and he stood up on his back feet and when he fell down, he put his paws right on his nose, like that. This girl, by this time, was right up there looking down at that. And the rattlesnake went over, and you know the way they do—they go up and down the body, noticing how long it is and whether it is still alive. Their auditory nerve is on their tongue. It then finally discovered that the mouse was in fit shape to eat. He went over and went through all his business and got his jaws on the edge and took this little mouse in his mouth. And she watched, oh, I think perhaps half an hour, until there wasn’t anything left but the tail of this mouse hanging out of the snake. John made a story out of it and gave it a lot of implications that probably were there.”

In his way, Toby Street agrees with Grove Day about the story’s Freudianism, as does Bruce Ariss, a Cannery Row legend in his own right. Bruce’s book, Inside Cannery Row: Sketches from the Steinbeck Era, identifies a tweedy, spinsterish dean from an eastern girl’s college as the woman in Doc’s Lab who became excited and told Ricketts she wanted to pay him to keep and feed the snake for her.

In his way, Toby Street agrees with Grove Day about the story’s Freudianism, as does Bruce Ariss, a Cannery Row legend in his own right. Bruce’s book, Inside Cannery Row: Sketches from the Steinbeck Era, identifies a tweedy, spinsterish dean from an eastern girl’s college as the woman in Doc’s Lab who became excited and told Ricketts she wanted to pay him to keep and feed the snake for her.

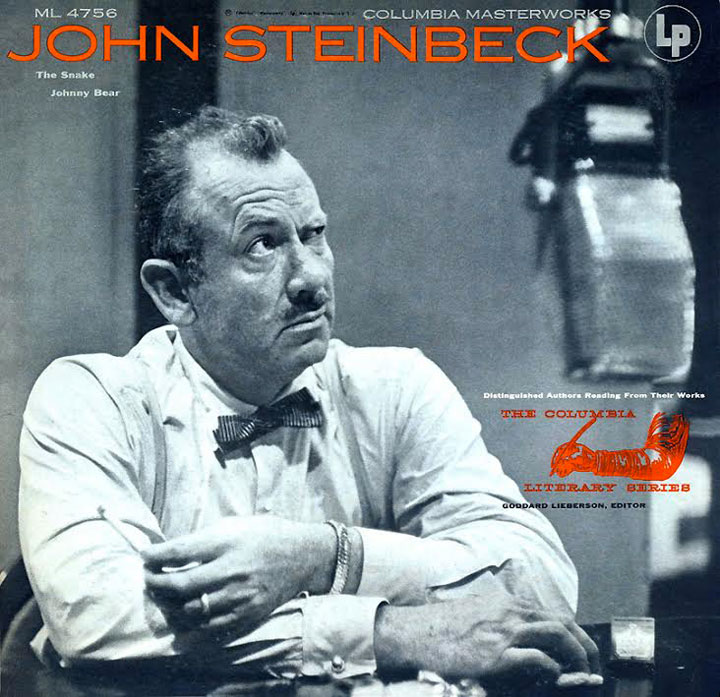

Frank Wright, another friend of Ed Ricketts from the 1940s, introduced me to “The Snake” more than 30 years after Steinbeck wrote his short story. Following Ed’s death, Frank became a member of the circle of men who saved Doc’s Lab, all friends of Monterey schoolteacher Harlan Watkins, who rented Doc’s Lab in the early 1950s before buying it from the Yee family (the real-life family of Lee Chong in Cannery Row). Watkins eventually sold the Lab to Frank and friends, and it was there that Frank first played for me the LP recording of John Steinbeck reciting “The Snake”—a dramatic way for any new reader to participate in Steinbeck’s provocative short story. Brought to life by Steinbeck’s distinctive baritone and experienced where the incident occurred, “The Snake” takes on a powerful feeling all its own. Friends lucky enough to have Frank as their Cannery Row guide continue to enjoy listening to John Steinbeck recite his story while visiting Doc’s Lab.

Frank Wright, another friend of Ed Ricketts from the 1940s, introduced me to “The Snake” more than 30 years after Steinbeck wrote his short story. Following Ed’s death, Frank became a member of the circle of men who saved Doc’s Lab, all friends of Monterey schoolteacher Harlan Watkins, who rented Doc’s Lab in the early 1950s before buying it from the Yee family (the real-life family of Lee Chong in Cannery Row). Watkins eventually sold the Lab to Frank and friends, and it was there that Frank first played for me the LP recording of John Steinbeck reciting “The Snake”—a dramatic way for any new reader to participate in Steinbeck’s provocative short story. Brought to life by Steinbeck’s distinctive baritone and experienced where the incident occurred, “The Snake” takes on a powerful feeling all its own. Friends lucky enough to have Frank as their Cannery Row guide continue to enjoy listening to John Steinbeck recite his story while visiting Doc’s Lab.

Now listen for yourself. Pay particular attention to what Steinbeck says before he recites the story. Though missing from printed editions, the compelling comments Steinbeck makes here about “The Snake” confirm how he liked to cover his tracks in his writing. Using the same phrase (“something that happened”) he employed elsewhere about other challenging subjects in his fiction, Steinbeck makes a funny reference to the sex-symbolism that distressed certain readers of “The Snake” from the beginning: “One of my favorite pieces of fan mail came from a small town librarian. She said it was the worst story she’d read anywhere; she was quite upset at its badness. Actually it isn’t a story at all. It’s just something that happened . . . . ”

Postscript: Steinbeck’s reading of “The Snake” and “Johnny Bear”—another short story from The Long Valley—was released in 1953 as a now-rare Columbia Literary Series record album. As noted, the details about the story’s origin provided by A. Grove Day in his letter differ in emphasis from those offered by Toby Street and Dook Sheffield, whose versions differ substantially from that of Bruce Ariss. As I thought about time and memory, another conversation with a friend of John Steinbeck came rolling out of the past. In 1983 I interviewed the great Joseph Campbell in Doc’s Lab, where he recalled the time “Ed called us all down to the Lab to watch him feed a rattlesnake.” Here is what Campbell had to say about “The Snake” that day on Cannery Row three decades ago.

Postscript: Steinbeck’s reading of “The Snake” and “Johnny Bear”—another short story from The Long Valley—was released in 1953 as a now-rare Columbia Literary Series record album. As noted, the details about the story’s origin provided by A. Grove Day in his letter differ in emphasis from those offered by Toby Street and Dook Sheffield, whose versions differ substantially from that of Bruce Ariss. As I thought about time and memory, another conversation with a friend of John Steinbeck came rolling out of the past. In 1983 I interviewed the great Joseph Campbell in Doc’s Lab, where he recalled the time “Ed called us all down to the Lab to watch him feed a rattlesnake.” Here is what Campbell had to say about “The Snake” that day on Cannery Row three decades ago.

John Steinbeck’s African-Americans—Author Susan Shillinglaw Clarifies the Context of the World War II Hero in “With Your Wings”

The publication of John Steinbeck’s “With Your Wings” continues to stimulate conversation about the writer’s understanding of African-Americans and the roots and relevance of his forgotten World War II short story about a black Air Force aviator. Last week Steinbeck scholar Robert DeMott challenged assumptions about the story’s origins. This week Susan Shillinglaw, author of On Reading The Grapes of Wrath and Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage, interprets the story’s African-American hero in the context of Steinbeck’s World War II experience and writings about African-American characters and issues. Like Robert DeMott, she responded generously to my request for expert comment about “With Your Wings.”

Susan Shillinglaw interprets the story’s African-American character in the context of Steinbeck’s World War II experience and writings about African-American characters and issues.

A professor of English at San Jose State University, she teaches the only regularly scheduled college-level John Steinbeck course offered anywhere. As Robert DeMott’s successor as director of SJSU’s Center for Steinbeck Studies, she introduced previously unpublished Steinbeck works of various kinds in Steinbeck Newsletter and Steinbeck Studies. These included the short story “The Kitten and the Curtain,” “The God in the Pipes”—an early fragment of what became Cannery Row—and an omitted chapter from the novel, “The Day the Wolves Ate the Vice Principal.” She wrote introductions for popular Penguin Classics editions of Steinbeck’s fiction, co-edited John Steinbeck’s America and Americans and Selected Nonfiction, and is co-editing a major Steinbeck reference work. Her 25-year record of teaching, editing, and writing was recognized by her designation as SJSU’s President’s Scholar in 2012-13. She is also Scholar in Residence at the National Steinbeck Center and co-director of a summer program on John Steinbeck for high school teachers funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

On Reading “With Your Wings”: African-Americans in John Steinbeck’s Life and Writing in and out of World War II

Susan Shillinglaw’s enlightening comments on the cultural and historical context of John Steinbeck’s World War II character William Thatcher, the African-American hero of the newly published short story “With Your Wings,” are quoted in full:

“This aviator, a second lieutenant with gold bars on his sleeves, would have earned his flight wings in Tuskegee, Alabama, where all African-American pilots were trained during World War II. ‘To have gone through the schools they must be very good, very intelligent and alert,’ Steinbeck writes in Bombs Away, a book-length propaganda piece published in 1942 on assignment for the U.S. war department in which Steinbeck lucidly explains the training of bomber pilots.

‘This aviator, a second lieutenant with gold bars on his sleeves, would have earned his flight wings in Tuskegee, Alabama.’

“Presumably Steinbeck produced ‘With Your Wings’ after writing Bombs Away and following his stint as a war correspondent covering England, North Africa, and a daring diversionary maneuver by Allied forces off the coast of Sicily and southern Italy. It’s tempting to think he wrote his short story after he returned from the front, where he might have encountered the Tuskegee Airmen, the 99th Squadron of the Army Air Forces first posted to North Africa in April 1943—four months before Steinbeck arrived at a ‘North African post,’ as in notes in Once There was a War, a collection of his World War II dispatches. Both Steinbeck and the 99th squadron then went on to Sicily, so it’s quite possible he knew and admired men like William Thatcher in this first African-American squadron posted overseas in World War II.

‘It’s tempting to think Steinbeck wrote his short story after he returned from the front, where he might have encountered the Tuskegee Airmen.’

“This aviator wants to detach from his 16-man group, to go home to ‘get something,’ to think about himself only. ‘He had thought to come home in triumph,’ a hero, a man set apart. But instead, like Tom Joad in The Grapes of Wrath, he discovers he is a group man, buttressed by family and community and ‘every black man in the world.’ That’s ‘something’ to hang on to.

‘Like Tom Joad, William Thatcher discovers he is a group man, buttressed by family and community and “every black man in the world.”‘