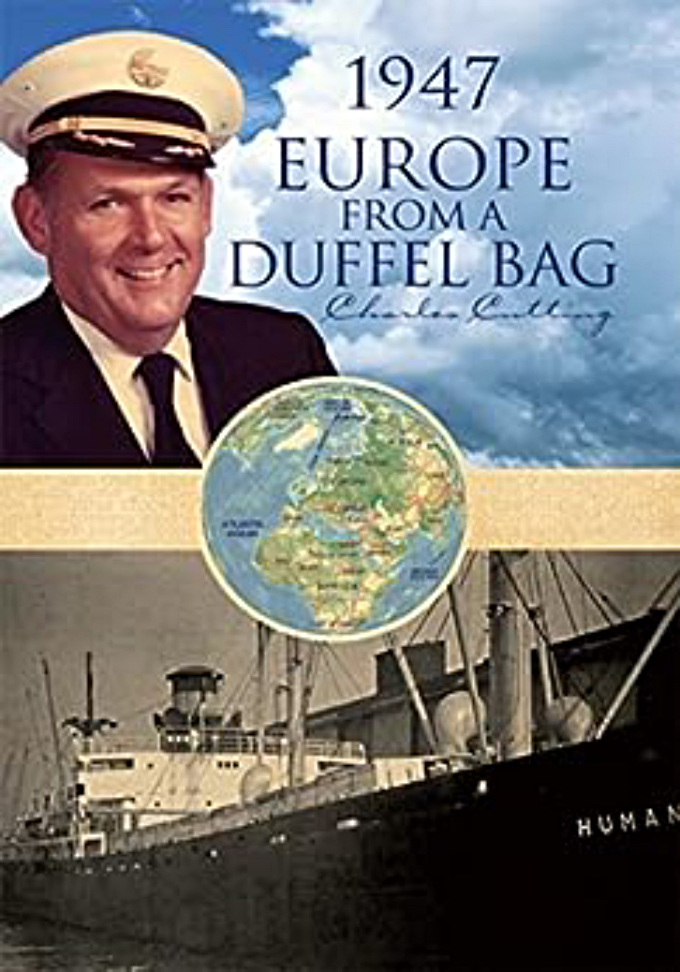

A chance Christmas dinner with John Steinbeck helped set the course of a young man’s life as an adventurer and Pan American pilot who crisscrossed the world many times–and then wrote a book about it. Charles Cutting honored Steinbeck by using the year of their meeting in the title of his book, 1947 Europe from a Duffel Bag. The book, which is available on Amazon, also includes harrowing and insightful experiences as a pilot.

“I was born in Pacific Grove, California, February, 1930,” Cutting writes. “My father as a young man worked down on Cannery Row in Monterey near our home in Pacific Grove. These were the days when the author John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts were well known. Because of this connection, I heard stories of these two men and some of their life and times.”

Cutting’s father, F. Douglass Cutting, had gone through a divorce and died when Charles was 12, Charles’s daughter Susan said. Charles’s grandfather, Francis Cutting–a superb plein air artist and Impressionist of the period–stepped in to help raise Charles. Francis would often take the boy with him when painting scenes along the California coast. The boy would play while the grandfather painted the land and sea around them.

Charles’s favorite location was Point Lobos, now a state reserve south of Carmel, and thought by many to be the inspiration for another writer of note who had connections to the Monterey Peninsula–Robert Louis Stevenson. It has been said that a tale about a hidden treasure at Point Lobos led Stevenson to write Treasure Island. But Charles Cutting mainly remembers it for the time spent there with his artist grandfather. When Francis Cutting relocated his studio from Pacific Grove to Campbell, California, he brought Charles with him.

“By 1946 I was attending high school in Campbell,” Cutting continued. “My girlfriend in those school days was a friend of one of John Steinbeck’s nieces. Through this connection in 1947 my girlfriend and I were invited for Christmas dinner at the home of Steinbeck’s sister [Beth Ainsworth, who ran a boarding house in Berkeley at the time].

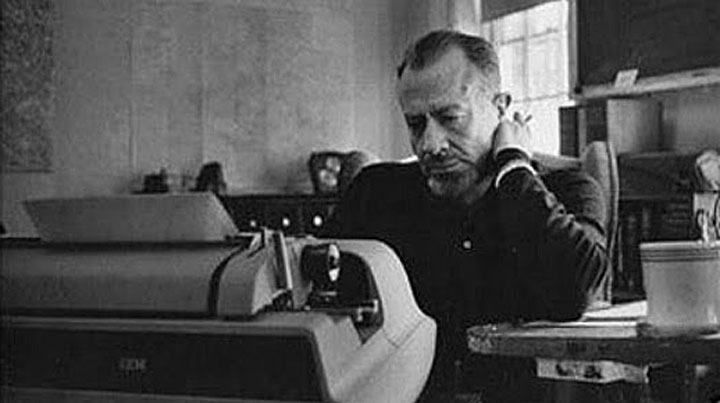

“As it happened, John came in unexpectedly from his reporting job in Europe and joined us for dinner. We had a warm visit and discussion of his just completed life in Europe. I was intrigued with his description of current events and life on the continent.

“One year later, I graduated from high school. After completing a summer of work, I combined my summer’s pay with my life savings for a grand total of $400. I set out to see for myself what John Steinbeck had talked about during that Christmas dinner in 1947.”

So at the age of 18, with his possessions in a duffel bag, Charles Cutting was off to explore a continent still recovering from World War II. That exploration would continue through his long flying career, including tense times, such as this expressed in one of his poems as his jet begins its climb over the Outer Hebrides: “Still our four engines strained upward through the vast blue void/Sharp sudden spasm and this machine becomes a problem child . . . .”

A Chance Encounter with a Masterful Painting

I met Charles Cutting by accident or, maybe I should say, by way of art. Driving home to Pacific Grove from San Francisco several decades ago, I stopped at the Red Barn weekend flea mart off Highway 101 to stretch my legs. I didn’t expect to find anything of interest; it was late Sunday afternoon and booths had been pretty well picked over. But in a large cardboard box I found an early 20th century oil painting of a cypress tree on dunes against a moody sky, likely painted in Pacific Grove’s Asilomar or at Point Pinos or nearby Pebble Beach. A beautiful painting, it was signed F.H. Cutting. Research showed that F.H. stood for Francis Harvey and that Cutting had exhibited prolifically, including the California Palace of the Legion of Honor and the Stanford Art Gallery, winning many awards in his lifetime.

Somehow, that led me to Charles Cutting. Or he contacted me when I inquired on the internet after his grandfather. Neither of us remembers exactly how it happened, but we got to know each other and Charles told me the Steinbeck story as well as stories of his career as a Pan Am pilot. Several years later, in 2007, he published 1947 Europe from a Duffel Bag. He once wrote me, “My encounter with Steinbeck was brief on that Christmas in 1947, but it did have an effect on my future life. I never forgot it.”