My most recent trip to the Monterey Peninsula as Visiting Scholar at the National Steinbeck Center was organized to further the Center’s connection to the increasingly diverse community of Monterey County and Salinas, California. Speaking at the Center about John Steinbeck’s career as a war correspondent in the context of the exhibit on Steinbeck at war was a real treat, as were my talks to John Wood’s high school English class in Salinas and the audience—mostly adult—attending a Saturday afternoon session at the Monterey Public Library. As a faculty member and administrator at Oklahoma’s largest public university, I make it a point to meet community groups whenever I can, and the individuals I encountered at each stop on my Monterey Peninsula itinerary came with interesting questions and intelligent insights about the author who helped make the region a literary legend. The library in Monterey is the oldest public library in California, and John Wood’s students are writing research papers on John Steinbeck, who attended high school in Salinas and college at Stanford. But the highlight of the trip was the time I spent with the youngest people on the schedule—fifth and sixth graders from area schools named for Cesar Chavez, John Steinbeck, and Dr. Oscar Loya, former superintendent of the Alisal school district east of Salinas. The kids’ energy was contagious, and their questions kept me on my toes most enjoyably. Their teachers and principals thanked me for coming, but on reflection the greater pleasure was mine. Helping to make John Steinbeck’s life and work relevant in children’s lives today can be a heady experience—one I recommend to those who, like me, research and write about John Steinbeck as faculty members at institutions of higher learning from Oklahoma to California.

John Steinbeck? Mais oui!

As a humorist I’ve learned that the best gags come from listening to people. Recently I broke one of my rules and picked up a couple hitchhiking on U.S. Highway 1, near Carmel, California. It turned out they were French and out to see the world, two things John Steinbeck liked most about life. When I asked them if they had read anything he wrote, the woman said oui! In France we read the raisins of anger! I liked her answer so much I put them up for the night and used the idea for “Life in the Grove,” the weekly cartoon I write for my home town newspaper, the Cedar Street Times.

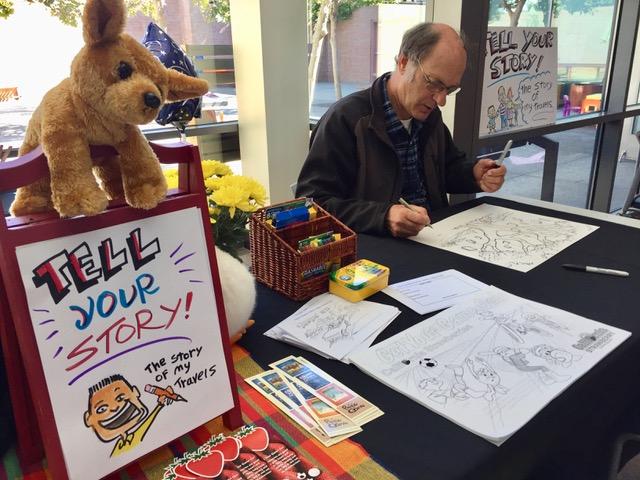

Photo of Keith Larson at 2019 Steinbeck Festival by Elayne Azevedo

Dog Days Dampen Festival

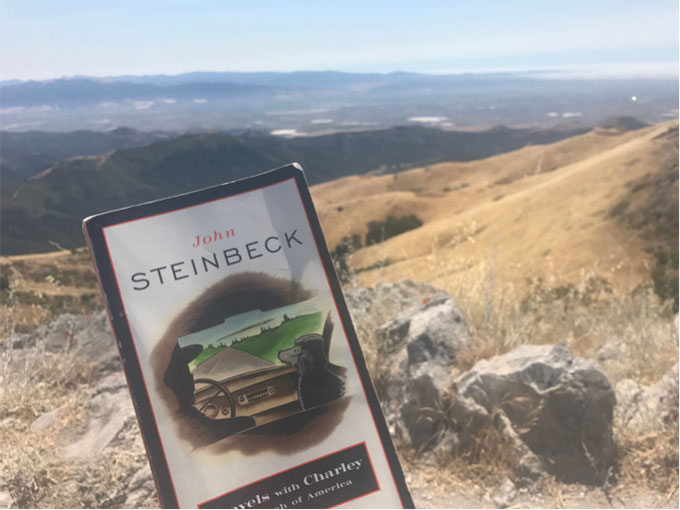

One spring morning at Alice’s Dog Park in Pasadena, a few of us dog owners were talking about traveling with your dog when a gentleman in his 80s, named Larry, mentioned Travels with Charley in Search of America by John Steinbeck, a fellow dog-lover and former Californian. When I got home I ordered the book on Amazon and, a few days later, began reading. Several pages into the opening chapter of Steinbeck’s autumnal road trip story, I called to recommend it to my dog-obsessed mother back in Louisiana. At her local library she learned the state system appeared to have only one copy, which she would have to special-request. When I got to the section on school desegregation in New Orleans, near the end of Steinbeck’s narrative, I understood why.

I’d been assigned to read Of Mice and Men and The Red Pony in high school, and I was familiar with the classic films made from East of Eden and The Grapes of Wrath, so I knew John Steinbeck was an important writer who created robust settings and raw-hearted characters with whom, for whatever reason, I could easily identify. But I knew little about the causes of the author’s deeply held concern for the undervalued and marginalized, and the fraying of America’s moral fabric. Travels with Charley sparked my curiosity about this side of Steinbeck’s career.

An internet search for the whereabouts of Steinbeck’s custom 1960 GMC pickup truck, the Rocinante, led me to the National Steinbeck Center in his home town of Salinas, located five hours north of Pasadena. I was delighted to discover that the upcoming Steinbeck festival, the center’s annual event, would focus on Travels with Charley, and that attendees would have a once-in-a-lifetime chance to board the Rocinante. The theme of the 2019 festival was dogs, so I bought tickets and drove to Salinas on Saturday, August 3 with my mother, my wife, and three teenagers—our two sons and a neighbor’s—along for the ride.

Travel to Salinas in Search of John Steinbeck

We left early and arrived at 10:00 a.m. expecting crowds of Steinbeck fans, dog lovers, and social justice types, all eager to chat up strangers about Travels with Charley, like my friend Larry. Instead, a handful of early arrivals were milling about as staff members set up for the 10:30 tour of the Rocinante that had piqued my interest in the festival. While we waited I gave our neighbor’s son a rundown on John Steinbeck. The mention of The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, and East of Eden drew a blank stare. The clue about East of Eden—“You know, one of the three movies James Dean made before he died”—caused a response. “Who’s James Dean?”

The Rocinante tour, led by Tom Lorentzen (a.k.a. John Steinbeck), was educational and entertaining, and there was something for everyone on the schedule for the rest of the day: a dog show, a walking tour of downtown, a writers workshop, a scavenger hunt and games for kids, a road trip scene-painting booth, a staged reading of Travels with Charley, a food-and-beverage fundraiser, live music, and more. The highlight for me was author Peter Zheutlin’s talk about writing The Dog Went Over The Mountain—a Travels with Charley-inspired narrative comprised of events and encounters experienced by Zheutlin during his six-week cross-country journey, in a BMW convertible, with his dog Albie.

Unfortunately, none of the crowds for the day’s activities topped 50, and by my count there were no more than 150 people, total, in attendance on August 3, the first full day of the festival. A white poodle—the single entry for the dog show—won Best Charley Lookalike, Best Dressed, and Best Personality. Scheduled for an hour and a half, the canine contest was over in five minutes. The kids games had few players, or none, and the photo booth was quiet. The bookstore looked empty. The food and beer booths, set up to raise money, were also lonely.

I’d read about large crowds at past festivals when I was doing my research, so I wondered what could have caused the drop in this year’s attendance. Was the change in date from early May to the dog days of August at fault, or was it the ticket price of $50-$60 for a festival that used to be free? Could teachers be to blame for declining interest among teenagers (like our neighbor’s son), who never read Steinbeck because he wasn’t assigned? Disappointed by the trip, I headed back to home to Alice’s Dog Park—In Search of John Steinbeck.

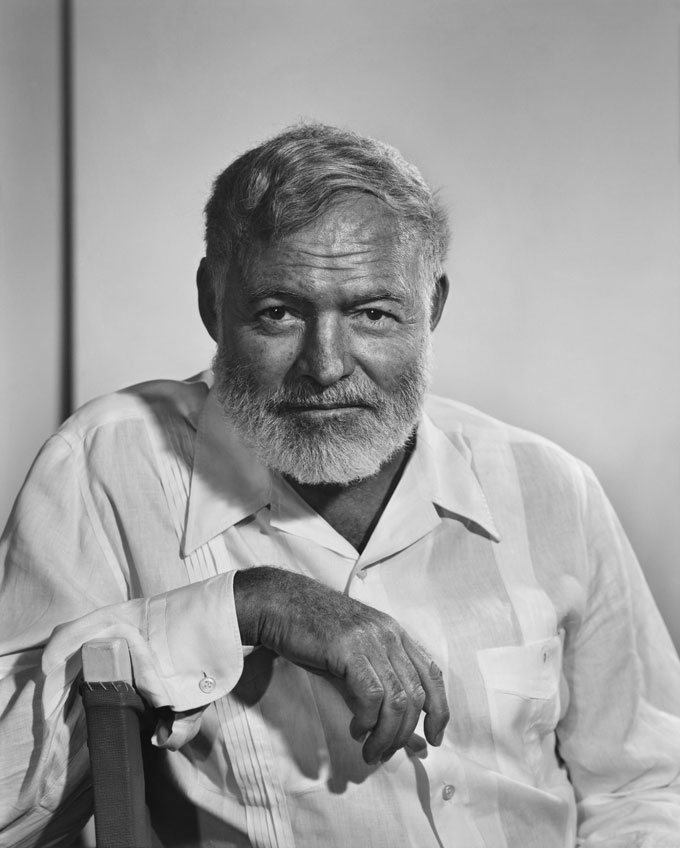

Talk on Ernest Hemingway Illuminates John Steinbeck

When Ernest Hemingway died, John Steinbeck suspected suicide and praised Hemingway’s writing, but knew Hemingway had disparaged his, viewing him as a literary competitor. Michael Katakis, the award-winning photographer and cultural critic who divides his time between Paris and Carmel, spoke recently about becoming Hemingway’s literary executor, editing Ernest Hemingway: Artifacts from a Life, and putting Hemingway and Steinbeck in comparative perspective as contrasting authors who remain popular with contemporary readers despite their differences. The recorded conversation took place on January 31, 2019 at the Carmel Public Library. Like the photography of Yousuf Karsh, the light it sheds on Ernest Hemingway also extends to John Steinbeck, whose life is the subject of a new biography by William Souder—scheduled for publication in 2020—that may comment further on the relationship of two figures with more in common than either ever acknowledged.—Ed.

An Evening’s Conversation: Ernest Hemingway and Traveling the World from Harrison Memorial Library on Vimeo.

Where First Reading Of Mice and Men in High School Led

I first read Steinbeck in high school. The book was Of Mice and Men, and I still remember how I felt when I finished. Lennie’s death was sad, but the final scene struck me as both necessary and beautiful, though I had yet to explore the paradox it presented. My world was black and white, filled with the naive explanations and simple solutions of boyhood. It had no room for ambivalence or complexity. Lennie was going to hang. George had no choice. What was I supposed to make of that at the age of 15?

Lennie was going to hang. George had no choice. What was I supposed to make of that at 15?

As my understanding of life and literature matured, I learned that philosophical questions lurked behind the emotional ending of Steinbeck’s novella-play. Was George justified in killing Lennie? What is justice? And who is the judge? What is the right response to a broken world? Above all, is there hope for healing? Spurred by these questions, I went on to discover subterranean levels of meaning in Steinbeck’s longer fiction, particularly in East of Eden, where the conflict of good and evil is clear but also complicated.

The Road from “Of Mice and Men” to “East of Eden”

“I believe that there is one story in the world, and only one,” Steinbeck wrote in the novel. “Humans are caught . . . in a net of good and evil . . . . There is no other story.” The moral dichotomy laid out by Steinbeck is simple in concept, but the narrative iterations in which it appears are endless. Steinbeck, whose world was never black and white, expressed this complexity throughout his work. He recognized the danger posed by the utopian revolutionary and the reactionary cynic alike, each attached to a false premise of possible permanence. Instead of certainty he sought balance, truthful balance, and he knew that relativity and change are rules imposed by nature.

Steinbeck, whose world was never black and white, expressed this complexity throughout his work.

An avid observer of marine life, Steinbeck writes like the changing tides, never claiming to know where one wave ends and another begins. Instead, he contemplates water hitting the shore and the adaptation required of all creatures to survive the shock, inviting readers to consider the process and the results. After Of Mice and Men, I began to appreciate the confounding complexity of existence and the responsibility of the individual to uncover meaning which Steinbeck embraced in his writing. “He’ll take from my book what he can bring to it,” Steinbeck said of his readers in a note to Pat Covici, his editor. “The dull witted will get dullness and the brilliant may find things in my book I didn’t know were there.” Steinbeck had done his part. Now, it was my turn to drive.

Steinbeck had done his part. Now it was my turn to drive.

Six years after first reading Of Mice and Men, I keep coming back to Steinbeck with a perspective that, if not brilliant, is deeper than that of high school. His work has not changed, but my understanding and appreciation have, and I’m writing fiction of my own. I’ve abandoned the passive interpretations of youth for the active ambiguity of adulthood, as Steinbeck had done at my age. Like Steinbeck and Ricketts searching the Pacific tide pools, I look below the surface of the prose I encounter and create, combing for balance and truth in the shifting sand.

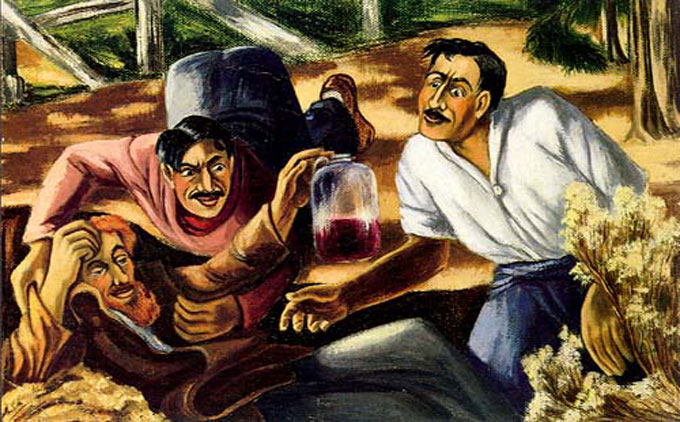

East Meets West in the Illustrations for Tortilla Flat

A number of years ago an art dealer on the East Coast called me in Pacific Grove, California to say he had access to the original illustrations commissioned by Viking Press for the deluxe edition of Tortilla Flat. Would I be interested in buying? I found a copy of the 1935 novel that gave Steinbeck his first dose of security, glanced at the illustrations for the 1947 edition, and promptly phoned the dealer. I liked Steinbeck’s fiction, but I had no clue that I would write a book of stories about him. It was the art dealer and lover of art who said yes that afternoon. The illustrations for Tortilla Flat, by an artist named Peggy Worthington, were exquisite.

The inside cover flap of the book was sketchy about her life but accurate in explaining how well illustrations mirrored Steinbeck’s colorful text: “For this new edition, Peggy Worthington, the artist, has done seventeen paintings in oil, here glowingly reproduced as full color illustrations and jacket. She spent much time in Monterey, and has admirably captured the atmosphere of both the setting and the kind of people of whom Steinbeck wrote. The strong, primary, human quality of the story is expressed in her paintings, and the result is a thoroughly handsome book to give and to own.”

When I asked the dealer for information, he said that Peggy was an East Coast artist who was rumored to have been a student of Norman Rockwell, the most celebrated illustrator of 20th century. He added that she might also be known as Peggy Worthington Best, for she was married to Marshall Best, a senior editor at Viking.

It wouldn’t have been surprising if she got the commission through her husband. Best is mentioned several times in Jackson Benson’s biography of Steinbeck, though the editor and the author weren’t close. Steinbeck’s editor at Viking, Pat Covici, was caught in the middle when conflict occurred, and Best was Covici’s boss. Peggy Worthington Best didn’t appear in Benson’s book, or anywhere else that I looked, but I bought two of the illustrations anyway. One shows Jesus Maria Corcoran polishing off a jug of wine, to the dismay of Pilon and Pablo. The other depicts Danny and Dolores in conversation over a picket fence. I wish I could have bought more, but money was tight and the price wasn’t cheap.

Both of the pieces I bought were included in the 1998 inaugural art exhibition of the National Steinbeck Center: This Side of Eden – Images of Steinbeck’s California, which I co-curated with Patricia Leach. From the Steinbeck Center in Salinas the show traveled to the Laguna Art Museum, accompanied by a brilliantly designed catalog by Melissa Thoeny and Glenn Johnson. The exhibition put our gallery on the map of Steinbeck’s California, and people started bringing in Steinbeck-related material—not just artwork, but letters and other important documents as well.

All of this eventually led to the book of short stories about Steinbeck’s life that I wrote and Steinbeck Books published in 2017. In 2008 we had created an exhibition featuring material brought in since 1998, along with the two illustrations from Tortilla Flat and other Steinbeck-related works of art. The title suggested by our friend Chris Carroll for the show—Steinbeck: Armed with the Truth—played on the idea of weaponry the way Steinbeck did when he wrote to a struggling novelist with the advice that “your only weapon is your work.” As in 1998, the show attracted a lot of attention. I still have Peggy’s picture of Danny and Dolores, but a buyer offered more than I could refuse for Jesus Maria, Pilon, and Pablo.

My curiosity about Peggy Worthington Best came to mind recently when I ran across collector copies of Tortilla Flat for sale online. Recalling the 1947 book blurb (“She spent much time in Monterey, and has captured the atmosphere of both the setting and the kind of people Steinbeck wrote of”), I realized how fully her art justified the praise. The clouds gathering over San Carlos Cathedral in one illustration, the mist drifting through the Monterey pines as the Pirate lectures his dogs, Danny and Dolores in front of her white board-and-batten cottage, so typical of Monterey and Pacific Grove past and present—everything looks seen.

Peggy must have kept a low profile when she visited. Assuming she came at or around the time of the Tortilla Flat commission, it’s possible that she (and perhaps her husband—though Benson doesn’t mention it) were hosted or helped by the author of the book she was illustrating. Less speculative than an encounter with Steinbeck in California is her relationship with an artist of equal stature in Massachusetts. This came to light recently, when a letter dated September 28 of 1961, addressed to “Peggy Worthington Best, Stockbridge,” came up for sale. The part quoted in the ad has the bones of a story by O. Henry: “Dear Peggy, since we are such good friends I just don’t want the news to reach you second hand. Molly Punderson and I are going to be married. I guess everyone in town will probably know this before long. I know you’ll be pleased for me.”

The seller of the letter in question is asking $1,000. A note to Peggy from the letter’s author sold for $250 or so some years ago. He had taken classes from Peggy in Stockbridge or Cambridge (versions differ) because his art had become tight and he wanted to loosen up. And he often sketched with Peggy. Who was the note-writer who wanted to brush up on his technique with the illustrator of Tortilla Flat? His name was Norman Rockwell . . . and he studied with her, not the other way around. Peggy Worthington may have been an East Coast artist, but East meets West in her work. Through it she came into contact with great artists on both coasts, including Norman Rockwell and John Steinbeck. Given time, who knows what other names will emerge.

Monterey Peninsula Chapter Closes in Bisbee, Arizona

Steve Hauk, the author of Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, is a fiction writer and dramatist. Here he recalls the late Bill Clements, the last character in the book of short stories he based on the life and times of John Steinbeck. Fortune’s Way, his play about the Monterey Peninsula artist E. Charlton Fortune, will be performed at Carmel Mission Basilica this Friday and Saturday.—Ed.

We lost another link to the world of John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts when Bill Clements died peacefully in his sleep last Saturday at his home in Bisbee, Arizona. Bill didn’t know Steinbeck or Ricketts, but when he lived on the Monterey Peninsula he met many people who did. The most important were Bruce and Jean Arris.

Bill didn’t know Steinbeck or Ricketts, but he met many people who did.

Bruce was an artist and author, and Jean was a writer, too. Together they drew Bill into their world when he first appeared on the Monterey Peninsula in the mid-1970s, a young Navy veteran driving an old pickup truck. Bill absorbed Bruce and Jean’s tales of the legendary 1930s so thoroughly that he became a storyteller himself, then an active part of the local scene.

Bill absorbed tales of the legendary 1930s so thoroughly that he became a storyteller himself.

When I came to write stories about this world, I included one on Bill that I simply called “Bill,” the last story in my collection, Steinbeck: The Untold Stories. Like everyone in the book besides Bill, Bruce and Jean were gone, and I was happy to close with a living character. In a sense, Bill’s death is the true ending.

I was happy to close my book with a living character. In a sense, Bill’s death is the true ending.

Bill was born in Philadelphia in 1944. An uncle was a professional boxer named Eddie Cool, a handsome, talented welterweight whose life ended badly. Once, talking about his uncle, Bill began to cry. He could be emotional, and that’s one of the reasons Bruce and Jean loved him so much. But they told him they loved him because he didn’t treat them like old people.

Bill could be emotional, and that’s one of the reasons Bruce and Jean Arris loved him so much.

Bill became a house painter, and though he never took a bad fall, the sandwich shop business he called Philly Billy’s failed and he worked part-time as a bartender. He lived in a rental home in Pacific Grove, and when people got in trouble, sometimes homeless, he rented them a room in his rented house, much like Danny’s boys in Tortilla Flat. This eventually got him into trouble with his landlord and the town. Being evicted convinced him to leave for Bisbee, Arizona, a place he also loved, though in the story I wrote I have him going elsewhere.

He lived in a rental home in Pacific Grove, and when people got in trouble, he rented them a room in his rented house.

Bill had lazy blue eyes and thick blond hair and a look like the actor Richard Widmark. One time he called the author Ken Kesey to ask him about writing One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, about shock treatments and lobotomies. When he got off the phone with Kesey he had tears in his eyes. He had a tender heart and a last name that meant mercy, and he went on helping others, as this Bisbee, Arizona interview showed last December.

Dogging John Steinbeck Getting a Hair Cut: True Story

The summer I was 12 years old, my step-grandfather Jimmy Tyson suggested that the two of us drive over to Sag Harbor, on Long Island, to meet John Steinbeck. Jimmy, as I called him, lived along the ocean in nearby Amagansett, in a renovated 18th century saltbox house that was authentic in every way. The driveway was long and meandered through a potato field—a signature feature of eastern Long Island when Jimmy and John were alive and Sag Harbor was a good place to be anonymous.

I knew who John Steinbeck was, but until Jimmy’s suggestion I had no idea that the author of The Red Pony, which I’d read at school, had a home in Sag Harbor. On that bright and sunny eastern Long Island day in 1961, the two of us got into Jimmy’s car—a blue Dodge station wagon—and drove the 15 or so miles from Amagansett. Jimmy knew where the Steinbecks lived, and when we pulled up to their modest Cape Cod style house, Elaine emerged to say that her husband was in town having his hair cut. They probably got hounded all the time, and I don’t know if she was nice to everyone or just to us because I was a kid, but I remember that she was friendly. Now I think about it, my grandfather might have brought me along for that very reason.

Jimmy knew where the Steinbecks lived, and when we pulled up to their modest Cape Cod style house, Elaine emerged to say that her husband was in town having his hair cut.

So we drove into Sag Harbor to the town’s only barbershop, parked, and went inside. Sitting in one of the chairs was John Steinbeck. I remember his face, bearded and distinctive, and he was a towering figure when he took jimmy’s hand, though I don’t recall if he shook mine. It was a short visit, and as we drove out of the parking lot we caught a glimpse of a large poodle—the soon-to-be-famous Charley—sitting in Steinbeck’s converted truck.

I was too young to feel intimidated when I met John Steinbeck. But I’m sure my grandfather realized the importance of the event, and that must have made it enjoyable for him. Thinking back, I wonder who benefited more—Jimmy in the moment or me, much later, in memory.

Photo of John Steinbeck with dog Charley in Sag Harbor courtesy of The New York Times.

Lifelong Learning Through Travels with Charley

Like most of the middle age-plus pupils in the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute classes I teach at the University of Richmond, I first read John Steinbeck’s fiction as a young adult. But I chose a work of nonfiction written by Steinbeck in middle age—Travels with Charley In Search of America—to open the course I teach in American literary classics. Before we begin, I advise those who read Travels with Charley when they were young, as I did, to disregard first impressions and read it again with fresh eyes. As Steinbeck observes at the outset of the journey, what we see is determined by how we view: So much there is to see, but our morning eyes describe a different world than do our afternoon eyes, and surely our wearied evening eyes can report only a weary evening world. You don’t even know where I’m going. I don’t care. I’d like to go anywhere. I set this matter down not to instruct others but to inform myself.

As Steinbeck observes at the outset of the journey, what we see is determined by how we view.

Later, discussing the book’s significance in middle age, we recall how we explored Steinbeck’s America in our teens and twenties—driving, and riding trains, buses, and planes; experimenting with ideas; testing the patience of people who were our parents’ and Steinbeck’s age during the turbulent decade of the sixties. For many of us, the need to experience our parents’ world through the “morning eyes of youth” was the reason we read Travels with Charley the first time around. Even in middle age, Steinbeck understood the impulse to escape: When I was very young, and the urge to be someplace else was on me, I was assured by mature people that maturity would cure this itch. When years described me as mature, the remedy prescribed was middle age. In middle age, I was assured greater age would calm my fever and now that I am fifty-eight perhaps senility will do the job . . . I fear this disease incurable.

Even in middle age, Steinbeck understood the impulse to escape.

Reading Travels with Charley in maturity gives my students renewed respect for Steinbeck’s courage in answering the call of the road by driving a fitted-up camper solo from one coast to the other, with his wife’s poodle as companion and a deep understanding that “after years of struggle that we do not take a trip; a trip takes us.” Steinbeck’s itinerary in 1960 included destinations he visited on book tours years before—places he visited without fully experiencing them—and avoided high-speed super-highways, which were spreading like cancer across the map of post-war America. Steinbeck’s recognition that “When we get these thruways across the whole country . . . it will be possible to drive from New York to California without seeing a single thing” resonates with us as we recall the places we passed through along the way and reflect on the influence Travels with Charley continues to exert on how Americans think America is or was or ought to be.

We reflect on the influence Steinbeck continues to exert on how Americans think America is or was or ought to be.

All of us are amazed that Steinbeck could travel cross-country incognito until he came to Salinas, the home town he abandoned in 1925, and some identify with the sense of rejection he felt from family members and friends who failed to understand the values and ideas he expressed in the books he wrote in the 1930s. Like Thomas Wolfe, he became a stranger among his own people, though he knew better than to blame them. “Through my own efforts,” he notes, “I am lost most of the time without any help from anyone,” and he recognizes lost-ness in the people and places he encounters in Travels with Charley. A waitress has “vacant eyes” which could “drain the energy and excitement” from a room. “Some American cities are like badger holes, ringed with trash . . . surrounded by piles of wrecked and rusting automobiles [and] smothered in rubbish.” Observed firsthand, the anger of housewives protesting school desegregation in New Orleans seems inhuman and insane. “I’ve seen a look in dogs’ eyes,” he concludes, “a quick and vanishing look of amazed contempt, and I am convinced that basically, dogs think humans are nuts.”

Like Thomas Wolfe, he became a stranger among his own people, though he knew better than to blame them.

We try to avoid issues of race in class (though everyone recognizes that they still exist). As Steinbeck notes, “A dog is a bond between strangers,” and because many of us are empty-nesters, we focus instead on Steinbeck’s feelings for his dog Charley, who “loved deeply and tried dogfully,” and on the improved status of pets in his writing after Of Mice and Men. Reading or rereading Travels with Charley opens middle-aged eyes to the need for connection and companionship Steinbeck felt at a time of life when sudden loss or change—in a family or a country or a culture—can lead to alienation, loneliness, and depression. Those who think and feel after 50 will recognize the danger of despair. John Steinbeck, who made lifelong learning a creative enterprise, responded by creating an adventure for himself and us that makes Travels with Charley rewarding reading at any age.

Photo of Osher Institute for Lifelong Learning class courtesy University of Richmond.

Text of Tribute to Geert Mak At Award Event in Holland

Bill Steigerwald (at left), the American journalist who wrote Dogging Steinbeck “to expose the truth about Travels with Charley,” accepted the invitation to address an audience in Holland that included Queen Máxima (right) when his friend Geert Mak (center), the Dutch journalist who wrote In America—Travels with John Steinbeck, was awarded the 2017 Prince Bernhard Cultural Prize. “My appearance at the ceremony for Geert Mak on November 27 in Amsterdam was a total surprise to Mak,” says Steigerwald. “It was like the old time TV show This is Your Life.” The text of the tribute to a friendship that started with Steinbeck is published here for the first time.—Ed.

Good afternoon. Thank you for inviting me.

Though Geert and I were born an ocean apart, and though he’s much smarter and far more accomplished than I’ll ever be, we have some things in common.

We’re both 70-year-old Baby Boomers.

We both started out life with lots of hair.

We both grew up to be journalists and writers.

And we both specialized in the kind of drive-by journalism that he used so masterfully in 2010 for what became his American history book, In America—Travels With John Steinbeck.

In America is a great mix of big-picture history, on-the-road journalism and progressive opinion. The Guardian newspaper called it “witty, personable and knowing”—and it is.

But perhaps the most impressive thing about it is that it reads like it was written by a lifelong American, not a longtime citizen of Europe.

As a way to show how big America is and how much it had changed in the previous 50 years, Geert came up with idea to follow the same route around the United States that John Steinbeck took in 1960 for his famous road book Travels with Charley.

It was a really good idea—and I had thought of it too.

That’s why early on the morning of September 23, 2010, exactly 50 years after Steinbeck left on his iconic 10,000-mile road trip, Geert and I each drove to the great novelist’s former house on Long Island, New York.

We didn’t bump into each other at Steinbeck’s place.

I left to catch the ferry to New England an hour or so before Geert and his wife Mietsie arrived in their rented Jeep Liberty.

For nearly two months, from Maine to California and down to New Orleans, the Maks and I traveled to the same places and even interviewed some of the same people.

For the record, as we journalists like to say, the Maks traveled like adults. They stayed in motels and drove responsibly.

I drove alone, as fast as a runaway teenager, often sleeping in my Toyota RAV4 in Walmart parking lots or beside the highway.

We never did meet on the road, but before Geert got out of New England he discovered that I was a day or so ahead of him.

He also saw I was posting a daily road blog on a newspaper website and slowly proving my case that Steinbeck had fictionalized large chunks of what was supposed to be a nonfiction travel book.

Geert, who already had his own suspicions about Steinbeck stretching the truth, realized he had to include me in his book.

Two years later, after a Dutch reader alerted me that my name was in In America, Geert and I were exchanging friendly transatlantic emails–in English.

We compared notes on Steinbeck and the road trip we shared.

I confessed to him that I was a lifelong libertarian, someone he’d call “a radical individualist.”

He confessed to me that he was “a typical latte-drinking, Citroën-driving, half-socialist European journalist and historian.”

Someday, we promised each other, we would meet in Holland over a Heineken and have a friendly debate about the two very different 2010 Americas we found along the same stretch of highway.

I never made it to Amsterdam–until now.

But in May of 2014, when Geert was in New York at a writers conference, he jumped on a plane and flew to Pittsburgh for three hours just to meet me and buy me lunch.

His visit was both an honor and a special treat.

He was even nicer in person than he was online. In addition to being a renowned European journalist and historian, he was clearly a great guy, a regular guy.

That’s a high compliment from an American, but I don’t think that’s news to many people in the Netherlands.

Hello, Geert. I’m a little bit over-dressed. But I’m here to buy you that beer.