I was nine when I discovered Google Maps. I was a demure little thing, sporting wispy baby hairs and crooked front teeth, but I sat in front of our family computer with the omnipotence of a goddess. I could go anywhere in the world; see the tip of the Great Pyramid of Giza or the cascading grandeur of Niagara Falls. After just a few clicks, I could declare proudly to my mom that I was a world traveler.

I sat in front of our family computer with the omnipotence of a goddess. I could go anywhere in the world.

But what I loved best was to zoom in on the United States. I zoomed to California, zoomed to the Central Coast, and zoomed to my hometown of Salinas, wondering if the suburban sidewalks and neatly lined lettuce rows of my life looked different from the sky. “Of course, people are only interested in themselves,” as John Steinbeck’s character Lee says in East of Eden. “The strange and foreign is not interesting – only the deeply personal and familiar.”

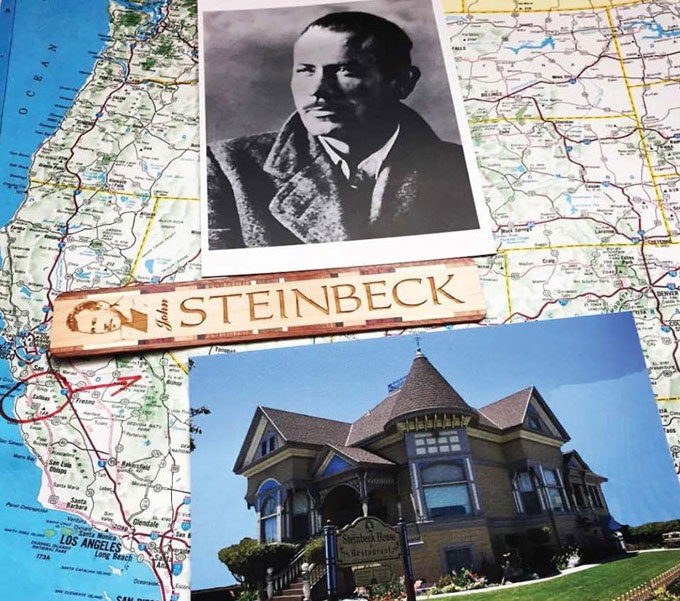

From Salinas, California to Stanford, Like the Steinbecks

By the time I turned 16, I was trying to make myself fall in love with places I did not know. Places that were not far away, but foreign nonetheless. What would it be like to live in San Francisco? San Jose? Los Angeles? How would I fare deciphering a train timetable or navigating the concrete capillaries of a city that scrapes the sky?

By the time I turned 16, I was trying to make myself fall in love with places I did not know. Places that were not far away, but foreign nonetheless.

In short, I wanted out of Salinas. I think that was the general feeling of my peers as well. The mountain ranges rising from the dark soil of the valley seemed a macro-enclosure, a way to trap us. As Steinbeck notes in “The Chrysanthemums,” “the high grey-flannel fog . . . closed off the Salinas Valley from the sky and from all the rest of the world,” making us feel as though we were stuck in the belly of a large “closed pot.” Scribbling away at SAT prep books felt like clawing at the walls. I knew a college acceptance was my ticket out, as it was for Steinbeck when he left Salinas for Stanford, followed later by his sister Mary.

In Journal of a Novel, Steinbeck’s record of writing East of Eden, he explained to his editor Pat Covici that he wanted to tell the story “against the background of the country I grew up in and along the river I know and do not love very much. For I have discovered that there are other rivers.” I knew that the Salinas is, as Steinbeck wrote in East of Eden, “not a fine river at all.” It wasn’t worth boasting about. Neither was the city of Salinas. When traveling out of town and answering the where-are-you-from question, I would quickly say “Monterey,” then quietly add “area.” Technically this face-saving half-truth wasn’t a lie, and when I entered Stanford as a freshman it also saved time. “I’m from Salinas.” Where? “Ever heard of Monterey?” Oh. Right.

I knew that the Salinas is, as Steinbeck wrote, ‘not a fine river at all.’ It wasn’t worth boasting about. Neither was the city of Salinas.

At Stanford, however, my relationship with my hometown started to improve. I suppose that to some degree all college students who flee the nest feel this way, but I think the proximity of Salinas to Palo Alto amplified the experience for me. I felt a wistful longing when I looked at photos of the rolling, golden hills that surround the Salinas Valley. Like Steinbeck, I missed the comforting landscapes of home.

The Stanford Course on Steinbeck That Opened My Eyes

One day in the dining hall during my second quarter at Stanford a friend from my dorm leaned over and said, “Jenna, you have to take the Steinbeck course with me.”

A friend from my dorm said, ‘Jenna, you have to take the Steinbeck course with me.’

Gavin Jones, the English professor my friend had a class with that quarter, was teaching a new course on Steinbeck in the spring. I had mentioned that East of Eden was one of my favorite books because—as Frank Bergon notes in Susan Shillinglaw’s collection of Steinbeck essays, Centennial Reflections—it made “the ordinary surroundings of my life become worthy of literature.” When I described Salinas to my friend, I realized I had strong feelings about the issues of socioeconomic inequality, gang violence, and racial tension that plague my hometown. I also saw that, like Steinbeck, my Salinas childhood shaped how I perceived Stanford and its surrounding community, from the groomed neighborhoods near campus to East Palo Alto, the other, poorer Palo Alto across Highway 101.

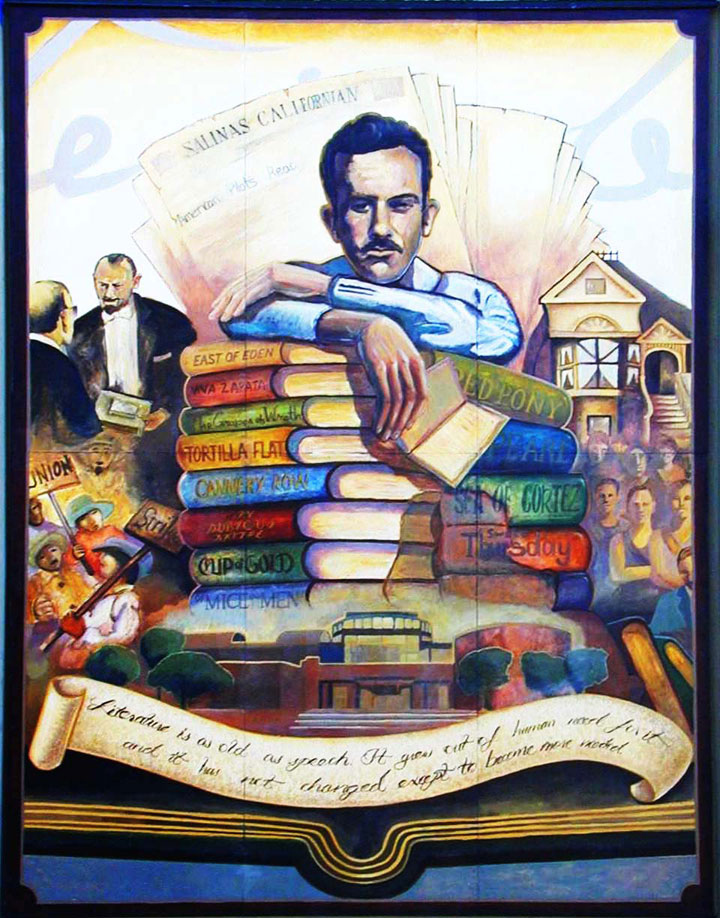

Although East of Eden wasn’t on the reading list for the Steinbeck course, a number of familiar titles were. The Red Pony, Cannery Row, The Pearl, The Grapes of Wrath: these were the school books with yellowed paper and dog-eared pages that I had read at Salinas High. When I was preparing for third quarter during spring break at home, I mentioned to my dad that I was ordering new copies of Steinbeck books for delivery to our address. “Don’t,” he protested. After rummaging in the garage, he emerged with a dusty box saved from his school years. Almost all of the Steinbeck books selected by Gavin Jones for the course had been languishing since my father used them, waiting to be rediscovered.

Almost all of the Steinbeck books selected by Gavin Jones for the course had been languishing in our garage since my father used them, waiting to be rediscovered.

On the first day of class I failed to arrive at the lecture hall early. My previous English classes had been small, quiet affairs, so I was surprised to see more than 120 students, buzzing with anticipation, already in their seats for Gavin’s course on John Steinbeck. As I readied my notebook I pondered Steinbeck’s reach. I knew he spoke out against injustice in his day and won the Nobel Prize in 1962, but not that he resonated with so many people more than a half-century later. I wondered how many lives he had touched over time, how many students in my Steinbeck class had seen the country of my childhood, and Steinbeck’s, through the golden lens of Steinbeck’s prose. Never thinking beyond the “closed pot,” I always assumed that my teachers had thrust his books into our hands just because we were in Salinas, not because we were part of the universal story Steinbeck told.

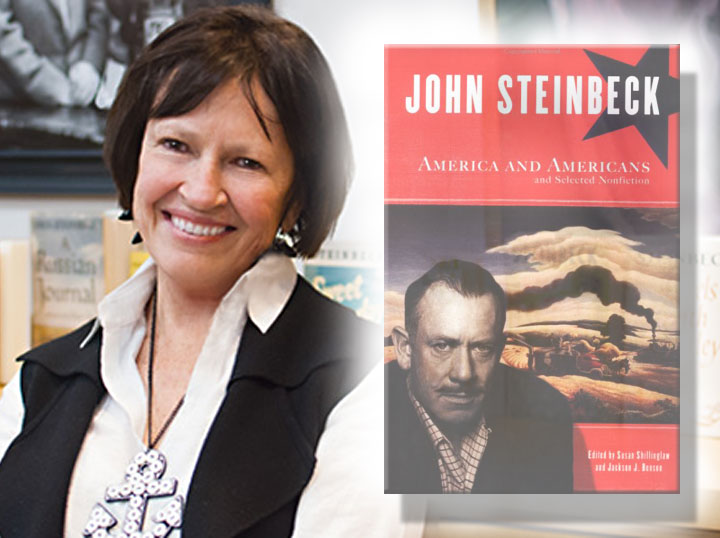

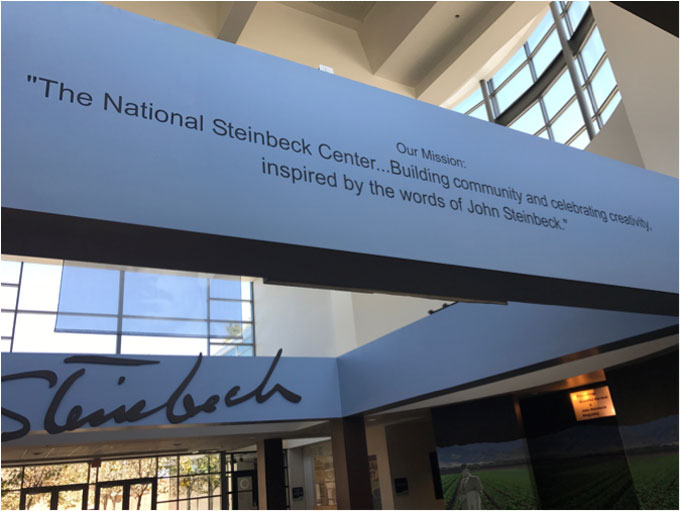

Over the course of the quarter I looked forward eagerly to class with Gavin. He embraced unconventional ideas, tracing behaviorism in The Red Pony and linking plants and humans in unexpected ways in “The Chrysanthemums.” He also brought in guest lecturers who expanded upon these themes and others. One of the lecturers was Susan Shillinglaw, professor of English at San Jose State University and director of the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, who discussed Steinbeck’s relationship with his first wife, Carol. Parts of her talk helped me better contextualize Steinbeck’s relationship with Salinas and the Monterey Peninsula.

One of the guest lecturers was Susan Shillinglaw. Her talk helped me better contextualize Steinbeck’s relationship with Salinas and the Monterey Peninsula.

Once I began to grasp Steinbeck’s central role in creating the region’s identity, I wanted to know more. The name Steinbeck was everywhere when I was growing up, attached to real estate companies, hotels, streets, and highways. How had the man behind the name shaped Salinas and the region? How had they changed since he roamed the hills of the Salinas Valley 100 years ago? What could characters like Lee and the stories of Steinbeck’s “valley of the world” teach me about growth, about spirit, about understanding and embracing human differences? I had a lot to learn.

The Summer Internship in Salinas That Opened My Heart

In Travels with Charley, Steinbeck returns to the Monterey Peninsula to revisit his California past one last time. Hoping for joy, he experiences disillusionment edged with despair. Slumping over a Monterey bar with his friend “Johnny,” he laments: “What we knew is dead, and maybe the greatest part of what we were is dead. . . . We’re the ghosts.” When I returned to Salinas for my first summer home, I decided to look toward the future instead of the past.

When I returned to Salinas for my first summer home, I decided to look toward the future instead of the past.

Thanks to Community Service Work Study, a Stanford program that funds internships at nonprofit organizations for eligible students, I was able to take an internship at the National Steinbeck Center, the museum and cultural center on Main Street in downtown Salinas. Over the course of the summer I wrote grant applications, learned about marketing and management, worked with Susan Shillinglaw on a new publication for Penguin’s Steinbeck series, and planned a poetry slam for the NEA Big Read, forging a deeply felt bond with my community. I can’t say where the winds will take me after college, or if I will ever live in Salinas again, but I hope I never have the sense of loss that overwhelmed Steinbeck’s homecoming in Travels with Charley. I hope I can return to the landscape that raised me with joy, tapping into the sense of deep belonging I feel when I see the soft sunlight falling on Mount Toro or inhale the mild breeze from Monterey Bay.

Over the course of the summer I wrote grant applications, learned about marketing and management, worked with Susan Shillinglaw on a new publication for Penguin’s Steinbeck series, and planned a poetry slam for the NEA Big Read, forging a deeply felt bond with my community.

Steinbeck echoed the novelist Thomas Wolfe in Travels with Charley: “you can’t go home again.” Nostalgia is hard to reconcile with new names and faces, with the attachment to growth and “progress” that Steinbeck came to distrust in America and Americans. Yet elements of Steinbeck’s California remain, and I have faith that pieces of my California will survive too. During my summer in Salinas I combed the streets around the Steinbeck family home on Central Avenue. I sipped chai tea in the Main Street coffee shop that was once a feed store owned by Steinbeck’s father. I ate lunch at the little café Steinbeck is thought to have frequented. In Monterey I lingered outside Doc’s Lab and listened to the sloshing of the sea and the distant cries of gulls swooping in the sky.

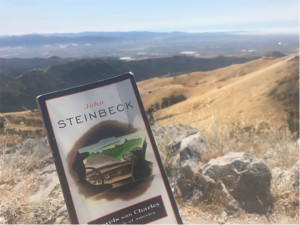

Before Steinbeck left home for the last time in Travels with Charley he did “one formal and sentimental thing.” He climbed Fremont’s Peak, the highest point in the Salinas Valley, and contemplated the places he loved—where he “fished for trout” with his uncle; where his mother “shot a wildcat”; the “tiny canyon with a clear and lovely stream” where his father burned the initials of the girl he loved on an oak tree.

Before Steinbeck left home for the last time in Travels with Charley he did “one formal and sentimental thing.” He climbed Fremont’s Peak, the highest point in the Salinas Valley, and contemplated the places he loved—where he “fished for trout” with his uncle; where his mother “shot a wildcat”; the “tiny canyon with a clear and lovely stream” where his father burned the initials of the girl he loved on an oak tree.

I followed John Steinbeck to the top of Fremont’s Peak on a warm Saturday in July. I felt the breeze cool the back of my neck as I contemplated the checkerboard of farmland below, the sun-kissed “valley of the world” celebrated in East of Eden and other books and stories. Close to the clouds, the air seems sacred up there, offering something bright and righteous to the open heart. Something pure. Something deeply personal and eternally familiar.