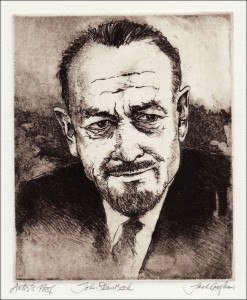

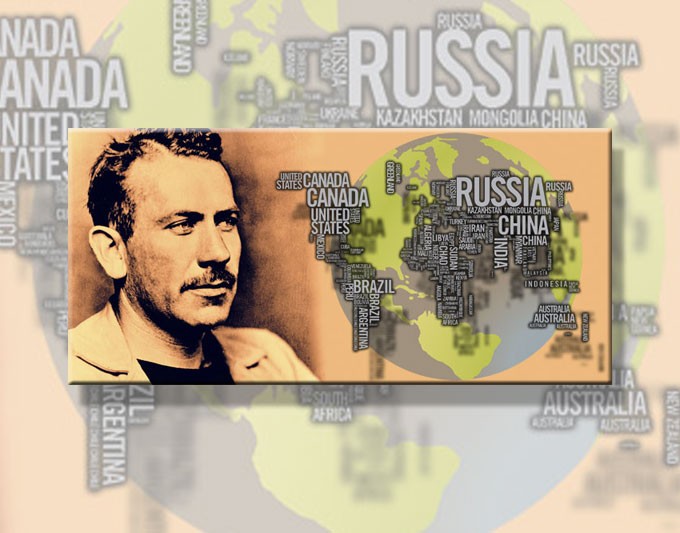

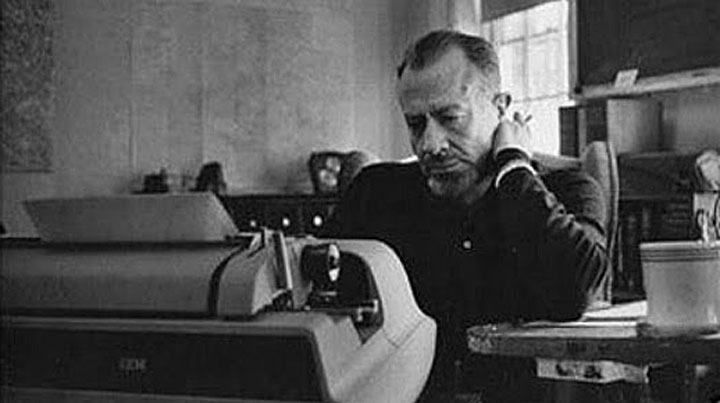

I was surprised when my friends Matt and Vivian told me about a silk opera cape that John Steinbeck wore long ago to a posh cocktail party in Pebble Beach. I didn’t doubt them (I knew them too well for that), but really—an opera cape with a red lining? It happened when they were visiting me at home during the time I lived in Monterey, California. Vivian noticed a book by Steinbeck on my writing table.

“Oh, we know him,” Vivian said, explaining how she and her husband Matt had catered the Pebble Beach affair, and how John sat alone in the corner at the party wearing a cape. “Anyone who wanted his attention had to go to him,” she added. “I thought he was being a snob. But when the party wound down he got up and spoke.”

Steinbeck said, “I’ve seen your side of the hill,” recalled Vivian. “Now who wants to see how the rest of the world lives?”

“And so off we went to Steinbeck’s house in Pacific Grove,” Vivian added, “where he showed us how to drink wine out of a gallon jug you propped on your shoulder.”

Listening to the story, I felt sure Steinbeck was giving the Pebble Beach crowd a two-fingered salute that night long ago. But I was left wondering about the cape, which seemed out of character for the writer. Years later I read a letter from Steinbeck to his soon-to-be second wife, Gwendolyn Conger, describing how a group of kids in Pacific Grove appeared at a neighborhood party dressed in capes. He said he thought it might be amusing if he were to venture out wearing one, too. Eventually he did. Mystery solved.

Celebrities Pass Through and Come Calling in Monterey

The more I think about my life surrounded by artists on Huckleberry Hill—a hill overlooking Pacific Grove and Monterey, California—the more I regret not asking more questions and listening to more stories about John Steinbeck during the 1930s and 40s. Years later, during my time there, celebrities who today would be followed by a gaggle of fans and reporters managed to live, work, and visit in peace. Famous writers in the region’s rich history included John Steinbeck, Robinson Jeffers, Dennis Murphy (the son of a childhood friend of Steinbeck’s), Eric Barker, and Hunter S. Thompson.

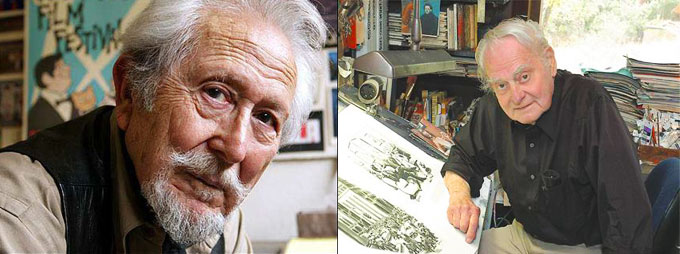

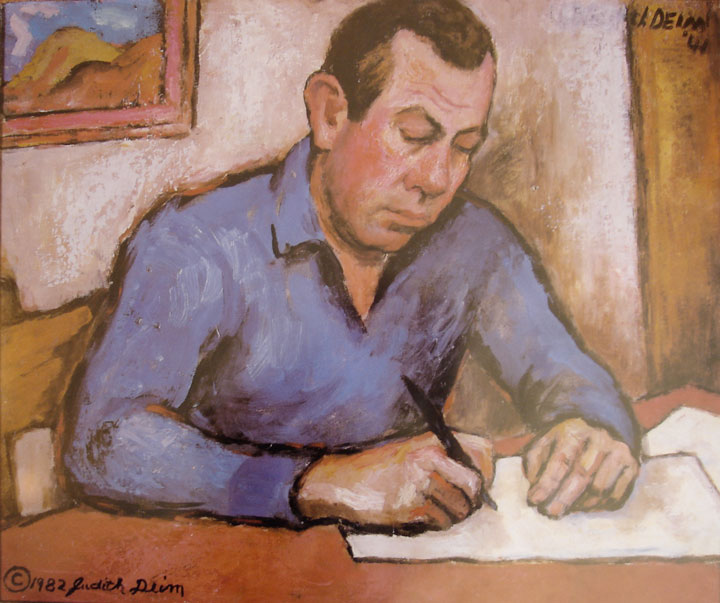

Among the motion picture stars who came to town were Marlon Brando, Steve McQueen, Shirley Temple Black, Doris Day, Bing Crosby, Joan Fontaine, Clark Gable, Kim Novak, and Frank Sinatra. Singers, too: Bobby Dylan and Joan Baez. Artists galore: Bruce and Jean Ariss, Ephraim Doner, Liza Wurtzman, John Steinbeck’s portraitist Barbara Stevenson Graham, who painted under the nom de plume Judith Deim. The art collector Bill Pearson, who owned a gallery in New Monterey, plus a flock of colorful cartoonists: Eldon Dedini, Hank Ketcham, and Gus Arriola. Photographers, some famous—Ansel Adams Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham—and others less well known: Morley Baer, John Livingston, Al Weber, Brett Cole, and Ruth Bernhard. Lesser literary lights called Monterey or Pacific Grove home as well: Ward Moore and Milton Mayer and Winston Elstob and Martin Flavin and Bob Bradford and Lester Gorn, to name a few.

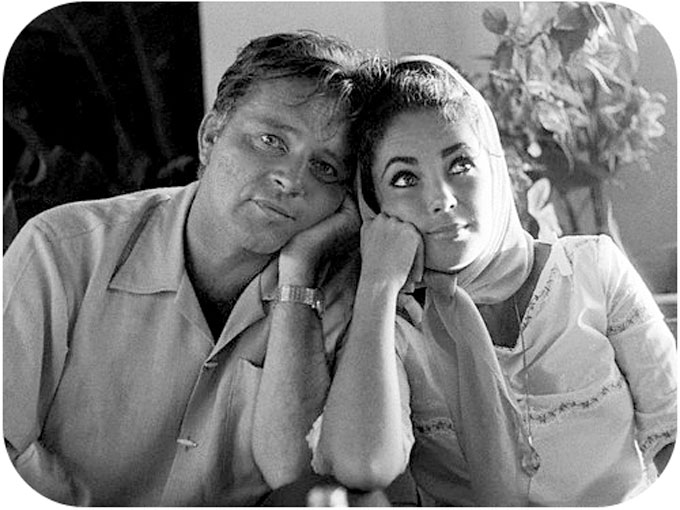

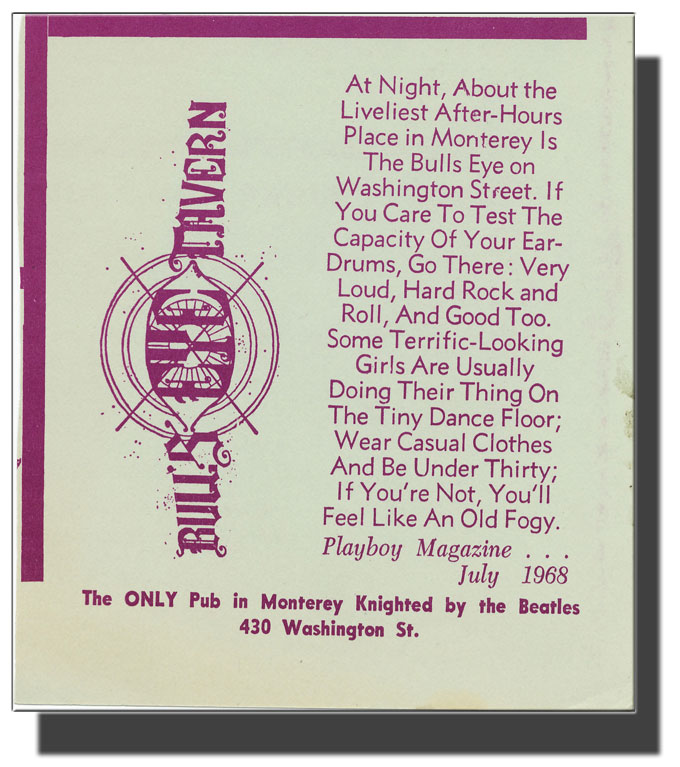

For the most part, prominent residents and visiting celebrities alike were treated by the denizens of Pacific Grove and Monterey, California, as friends or neighbors or passers-by who deserved privacy, like everyone else. Alcohol was often in evidence, and it was tolerated, even in formerly-dry Pacific Grove. Before my time the poet Dylan Thomas had passed through, driven by a wealthy woman from Berkeley in a yellow convertible. I was there when Liz Taylor and Richard Burton drank and argued and threw martini glasses at one other in a local bar. The racing driver Augie Pabst drove a car into a downtown motel swimming pool. Harold Maine, the author, visited a friend and drank all the aftershave in the bathroom. At the pub I owned in Monterey, Kenneth Rexroth leaned over and whispered, for my ears only: “I write poetry to fuck girls.” During the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival virtually every important rock musician in America paraded through my doors. The great jazz monologist Lord Buckley (“The Naz”) crashed one of my parties and gave a fireside performance that lasted well past dawn.

When a very young Diana Ross came to my bar, the Bull’s Eye Tavern, with the Supremes, a pub patron helpfully pointed out that they might not be of drinking age. I just shrugged. I figured that if I got tagged for serving these minors, the publicity would be worth a fortune. When Janis Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company hit town, they parked their canary-yellow Ford Anglia outside the Bull’s Eye and came in to drink, play darts, and play music. (Better music than darts, as I recall.) To me, it was clear from the size and condition of the car they left at the curb why Janis sang “Oh Lord, won’t you buy me a Mercedes Benz?”

Singers, Gangsters, and Royalty—All in Town for Fun

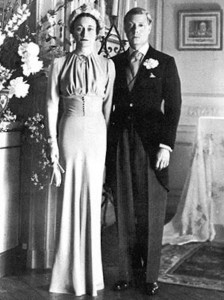

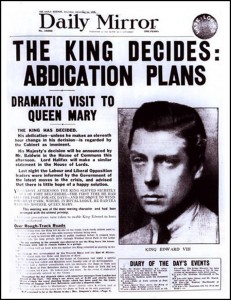

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor once stood six feet from me, gazing down at a flower garden I was constructing at a home in Pebble Beach. We exchanged smiles, as I was to do on a different occasion looking into the face of an aged and wrinkled Clark Gable. Bing Crosby saw me one afternoon and mistook me for his son. “Gary! What in the hell are you doing there?” he shouted in my direction. At the time I thought he had a vision problem, though it seems the problem may have had more to do with drink, as the man was rarely sober. He owned a house in the area that served as a party retreat for his boys. One day a young soldier from Fort Ord appeared at the Polygon Bookshop on Cannery Row. Leafing through a book of photos by Ansel Adams, he said wanted to be a photographer and would give his right arm to meet Adams. Winston Elstob, the writer who co-owned the Polygon with Jim Campbell, picked up the phone and dialed Ansel’s number. Within 30 minutes Adams arrived at the bookshop in his old blue Cadillac and spent an hour or more talking with the lad.

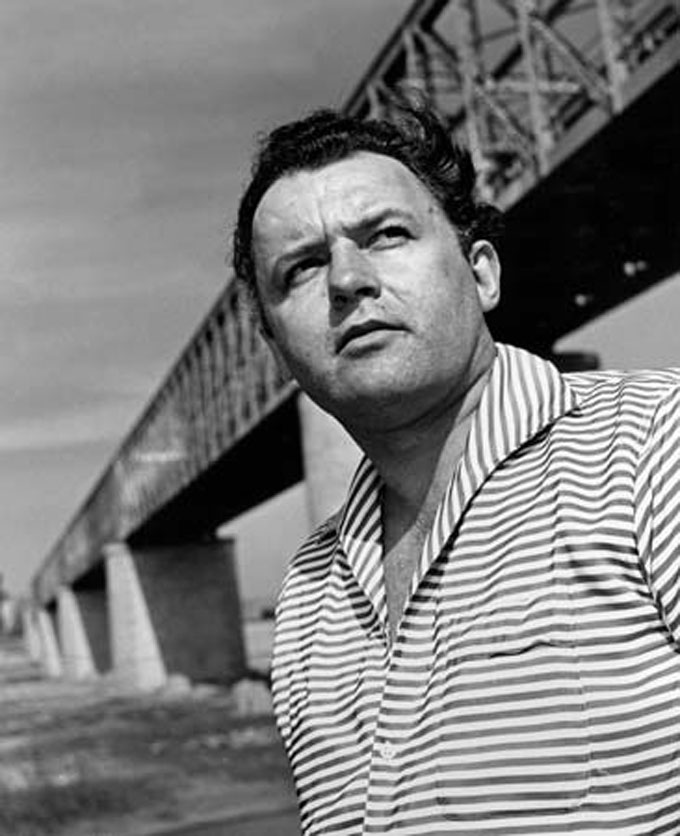

Cannery Row was a Monterey magnet, then as now. One evening I dropped into a coffeehouse bar where Bobby Dylan and Joan Baez, along with Richard Farina and Joan’s sisters Pauline and Mimi, sat in a corner singing quietly, playing guitars, and plucking a dulcimer. Los Angeles, a day’s drive, was a draw for locals like me—and vice versa. While visiting friends there, I met a screenwriter named Lionel Oley. Liking what I had to say about life in Monterey, he immediately moved north to join the Monterey-Pacific Grove fun. I located a rental house for him around the corner from mine on Huckleberry Hill, and his boyhood friend Rod Steiger often visited. After returning to Los Angeles from one trip to Monterey, Steiger observed that it never rained in LA, then took off his trench coat and handed it to me.

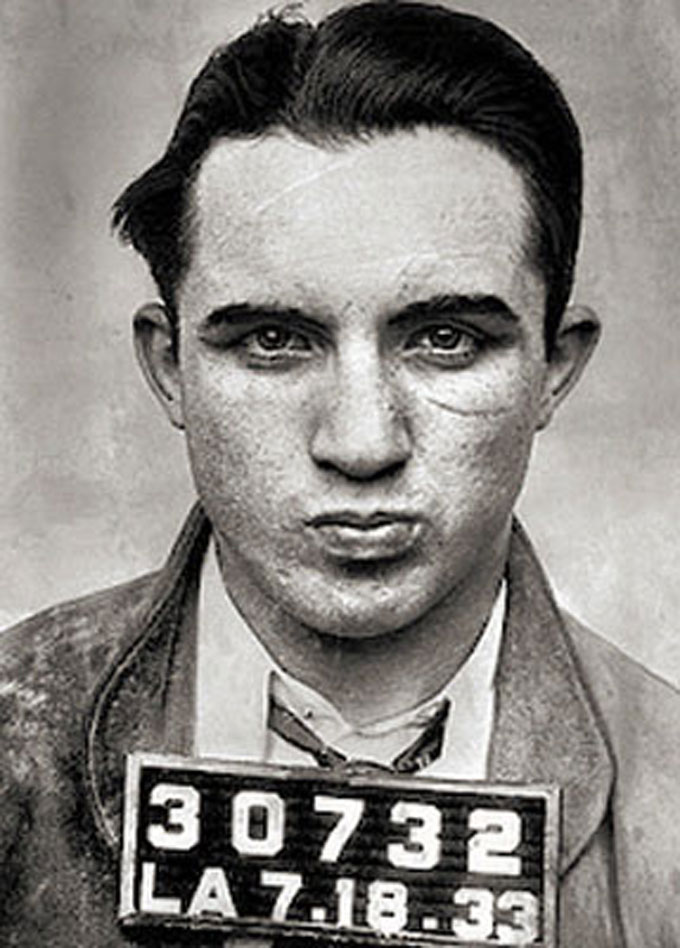

Lionel’s girlfriend moved up to Monterey as well, bringing with her a friend who was the mistress of the gangster Mickey Cohen. Mickey became a frequent caller, driving up from Los Angeles in his big bullet-proof car. The attractive business card he handed me identified him as the proprietor of a Los Angeles ice cream parlor. It was difficult going anywhere with Mickey because he would spend half an hour or more obsessively washing his hands, then go back inside to the bathroom to wash them again. Knowing his violent past, I was sure he was scrubbing away imaginary blood. One time, sitting in the back of Mickey’s car, the girlfriend rubbed her palm across the thick glass window and said, “I wish someone would start shooting so we could see if this damned stuff works.” Mickey shuddered visibly.

When Living in Monterey Was Like a Motion Picture

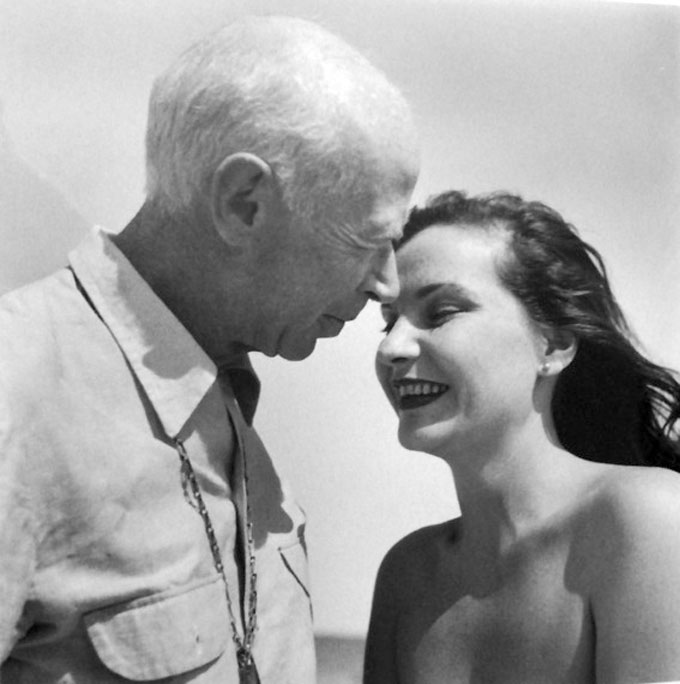

John Steinbeck’s Big Sur, down the coast from Pacific Grove and Monterey, California, was a powerful lure for writers and artists. The author Henry Miller, Big Sur’s genius loci, would sit on his sofa opening a large mailbag delivered to his mailbox at the foot of Partington, his wife Eve at his side, putting the letters with money into one pile and those without cash in another. The wonderful English poet Eric Barker lived nearby in a house on a cliff overlooking the ocean.

I was writing, too. One day a man named Roland—a friend of my friends, the artists Bruce and Jean Ariss—approached me at Big Sur’s legendary Deetjen’s inn holding a photograph album. Years earlier he had lived in Taos, New Mexico, near D.H. Lawrence and Lawrence’s wife Frieda. He asked if I would I help him write a book about the experience, showing me photos taken in the late 1920s that included one of Frieda mounted on a horse, looking quite large. I said yes, and we agreed to meet at my house on Huckleberry Hill the next day to get started. Alas, poor Roland never arrived: he died of a heart attack that night.

Motion picture people were attracted to the Monterey area for obvious reasons. During my time, a would-be actor named Ron Joy lived next door to my neighbor Lionel. Bucking the northbound trend, Ron headed south to Hollywood, where he failed as an actor but eventually achieved success as a movie magazine photographer. After getting engaged to Nancy Sinatra, he drove her up to Monterey in his little red MG roadster. If you’ve ever ridden 400 miles up and 400 miles down Highway 1 in the bucket seat of an MG, you, too, will understand why she stutters and looks so jumpy in her movies. I had a house party one night, and somehow Ingrid Bergman’s daughter Pia Lindstrom and a girlfriend from Sweden heard about it. They were staying at a Monterey motel and took a cab to my home, where they arrived unannounced and ended up spending the entire weekend. The Bull’s Eye Tavern prospered.

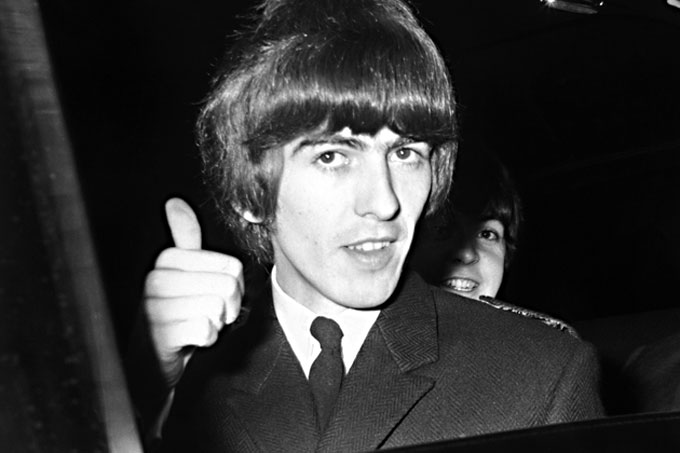

After Playboy magazine published an item about the Bull’s Eye that said my pub was the only place to go in Monterey, George Harrison and Ringo Starr appeared one evening with an entourage that included Neil Aspinall, Mal Evans, and Derek Taylor. After I closed, I invited them all to my house, where George told me that the Beatles were history. “Listen again to ‘Here Comes the Sun,’” he confided. After returning to London, he made me an honorary member of the Apple Corps, and I still have the ceramic green apple broach George sent me to prove it.

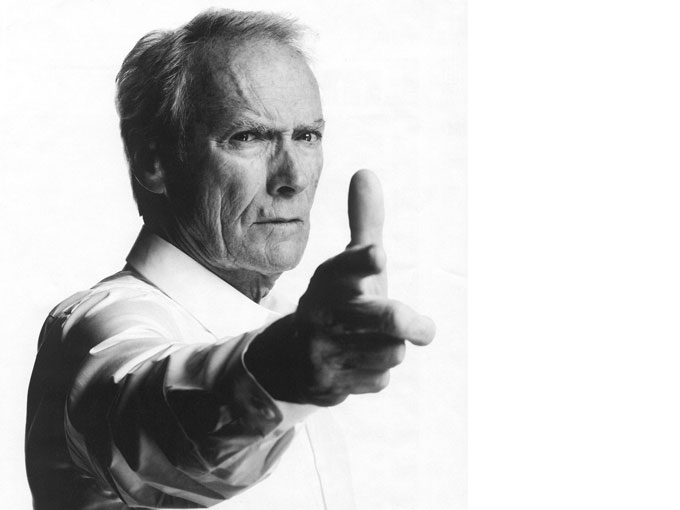

Carmel, south of Pacific Grove, has had its share of celebrities, too. The same week the Beatles came to my bar, Clint Eastwood—later the mayor of Carmel—walked into the Bull’s Eye with his friend, the golfer Ken Green. Even then, long before Dirty Harry, Clint was known to throw a punch at people with beards and long hair. “John,” he assured me, “I wouldn’t bust up your place. You’re a writer, and I respect that.” (Lucky me.) At a garden party in Carmel Highlands, the actor-screenwriter-producer John Nesbitt invited me to move to Los Angeles to work on his film series, The Passing Parade. Laughing, I said I wouldn’t give up a day in Monterey for a year in LA, even to work for him.

Because of its beauty and location, the Monterey-Pacific Grove-Carmel coast drew motion picture directors and stars almost from the beginning. When work was over, actors and writers sometimes stayed behind to live and play. During my years on Huckleberry Hill, it seemed that a picture was being shot every month somewhere between Monterey and Big Sur. If you were in the right place at the right time, there was a good chance of getting work as an extra, though a common complaint was that filming was one of the most boring jobs in the world. Shooting sometimes began before dawn and extended through the night. The tedious part for an extra was standing by as the director shot and re-shot the same scene—a little like Mickey Cohen, my gangster acquaintance, washing his hands while the rest of us waited.

Inadvertently, I almost appeared in a scene from a motion picture called Kings Go Forth when I happened to be in Martin’s Fruit Stand on the Carmel Valley Highway as the crew was shooting in an orchard behind the store. Frank Sinatra sauntered over, dressed in an army uniform for the scene, to buy an apple. Thinking back recently to my encounter with Ol’ Blue Eyes, I found a website that lists hundreds of films made around Monterey, California. My memory was further refreshed by the Monterey County Film Commisssion’s map showing where specific scenes were shot.

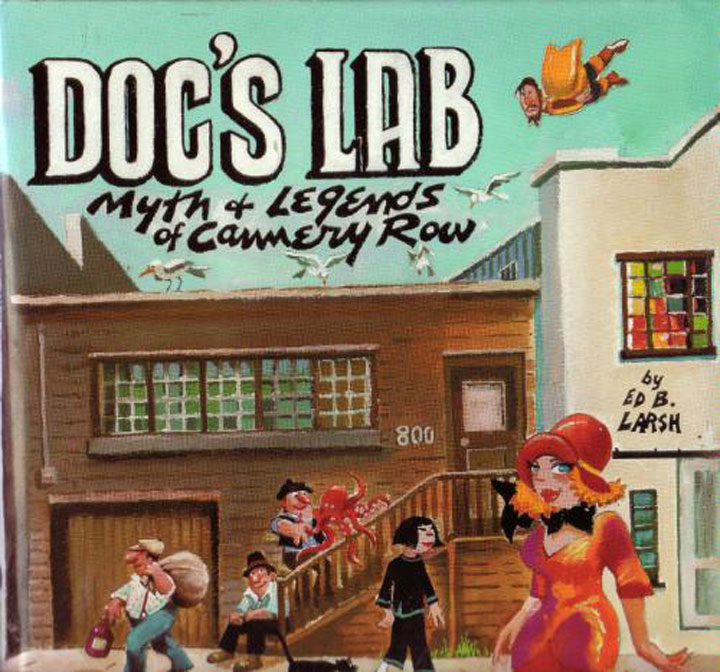

John Steinbeck, Bill Saroyan, and the Company They Kept

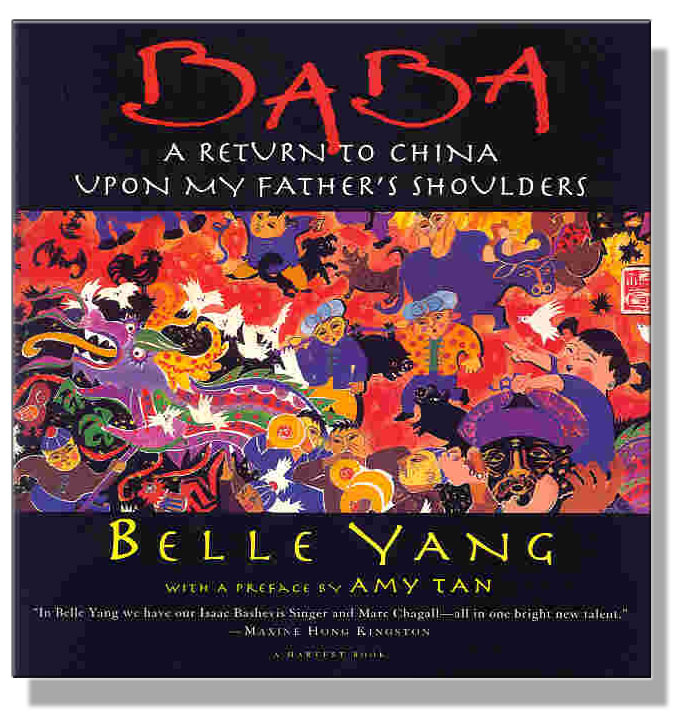

Like John Steinbeck, a handful of major writers, artists and actors of note lived in Monterey before they became famous. In Steinbeck’s era (and mine), the community offered kinship, support, and a quality of privacy that, for celebrities today, would require a wall and bodyguards to achieve. My home in Steinbeck’s old neighborhood and my pub downtown attracted an assortment of characters—famous, infamous, and struggling—not unlike Doc’s lab in Steinbeck’s day. We were all of us, in our own way, aiming for the top. Some succeeded and moved on, like Steinbeck. Others failed. I was among those who eventually left; though success spoiled Monterey for Steinbeck, my memories are mostly happy ones. If my friends Bruce and Jean Ariss were still alive, I’d talk with them about their friends Carol and John Steinbeck: about Ed Ricketts; about Steinbeck’s fellow California writer William Saroyan; about Burgess Meredith, Charlie Chaplin, and the composer John Cage, all friends of Steinbeck at one time or another. If I were rewriting the past and directing this particular picture, I’d get poor Roland to the Monterey hospital in time, and I’d add a scene for Roland to share his stories about D.H. and Frieda Lawrence in Taos—a place, like Monterey, where the stars shone brightly in a bygone era.