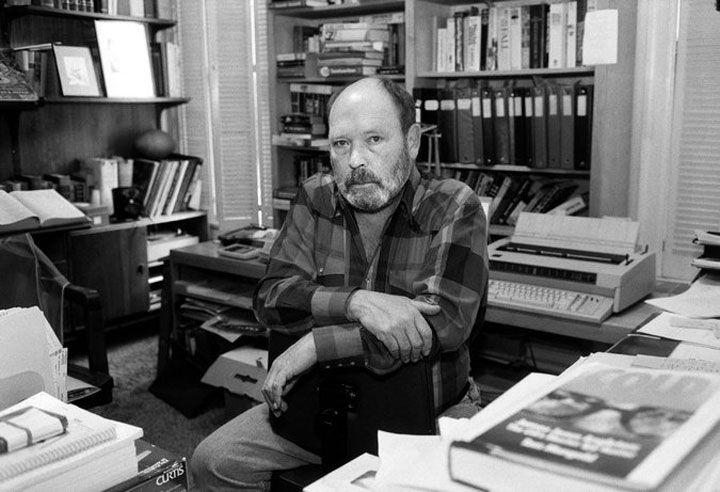

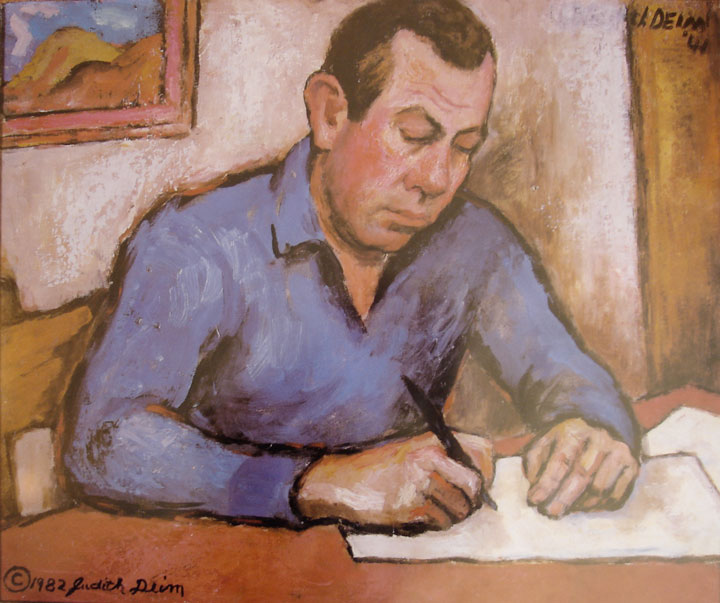

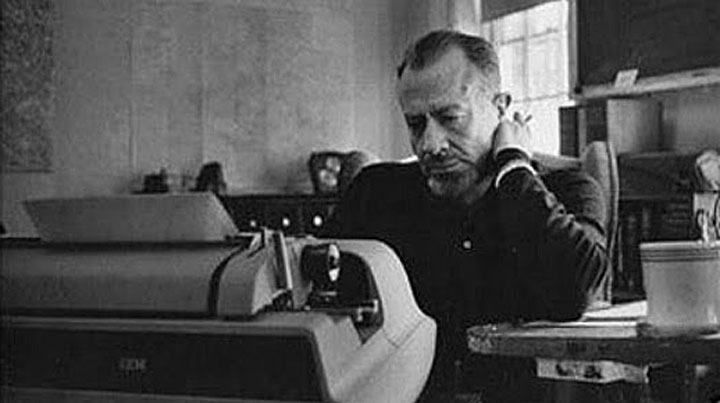

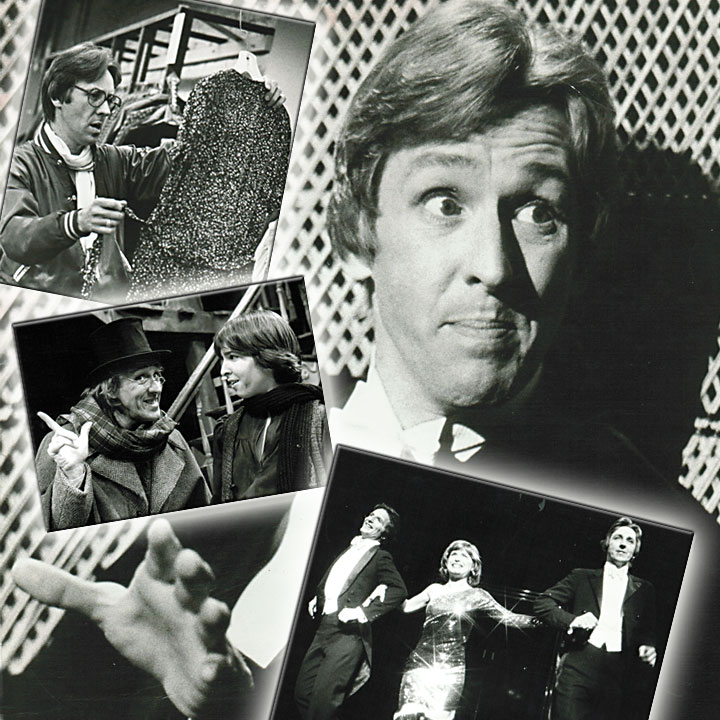

The death of the San Francisco freelance writer Curt Gentry on July 10 made me especially sad. An old-school journalist, a loyal fan of John Steinbeck, and a fearless writer about subjects close to Steinbeck’s divided heart (J. Edgar Hoover, San Francisco whorehouses), he helped me greatly when I researched Dogging Steinbeck, my true account of Travels with Charley, Steinbeck’s so-called non-fiction book. Curt Gentry was a gentleman, and one of the nicest guys I ever met.

Helter Skelter, J. Edgar Hoover, and Travels with Charley

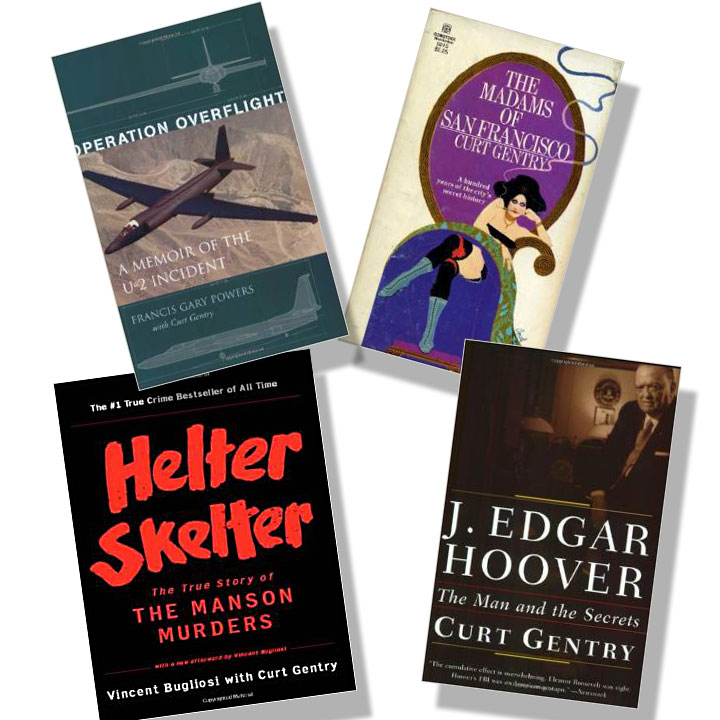

As noted in his San Francisco Chronicle obit, Gentry made his fame and fortune co-writing Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders, and a devastating biography of John Steinbeck’s dark nemesis, J. Edgar Hoover. Controversy and power never frightened Curt. Among his 13 books were histories of the downing by the USSR of an American spy plane during the Eisenhower Administration, detested by Steinbeck, and of the legendary madams who made San Francisco famous and, for Steinbeck, appealing.

From the mid-1950s until his death, Gentry lived in San Francisco’s trendy/hip North Beach neighborhood. In late October of 1960, Steinbeck pulled into town with his wife Elaine and their dog Charley on the California leg of the author’s Travels with Charley road trip to rediscover an America he said he no longer understood. Gentry deftly landed an interview with his literary hero and wrote a long piece for the San Francisco Chronicle about what Steinbeck told him.

In late October of 1960, Steinbeck pulled into town with his wife Elaine and their dog Charley on the California leg of the author’s Travels with Charley road trip . . . . Gentry deftly landed an interview with his literary hero and wrote a long piece for the San Francisco Chronicle about what Steinbeck told him.

Fifty years later, Gentry was one of the first people I tracked down when I began my research before I wrote Dogging Steinbeck, a book that reveals how Steinbeck and his editors at Viking padded Travels with Charley with fictions and fibs, then passed it off as a work of nonfiction for half a century. In The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer, Steinbeck’s biographer Jackson Benson mentioned Gentry’s San Francisco Chronicle piece without giving the young journalist’s name.

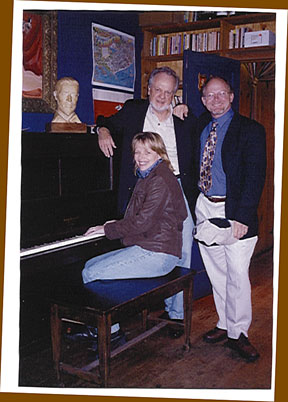

Thanks to the San Francisco Public Library and the Internet, I found Gentry’s address and phone number and called him from Pittsburgh to ask for his help retracing Travels with Charley for my book. How would the man who exposed Helter Skelter and J. Edgar Hoover but admired Steinbeck react when he heard I was trying to piece together his hero’s actual (as opposed to imagined) Travels with Charley? He replied he’d be happy to meet me for lunch whenever I was in San Francisco. I met with him twice, on two separate trips, during long, memorable lunches at nearly empty North Beach restaurants.

“Steinbeck Meets the Press” During Travels with Charley

Here, in this “Steinbeck meets the press” excerpt from Dogging Steinbeck, is what Curt Gentry told me about his encounter with John Steinbeck at Steinbeck’s San Francisco hotel during Travels with Charley in 1960:

“Headquartered at the St. Francis, Steinbeck hung out with old friends at some of the city’s top bars and restaurants. The local print media instantly discovered his arrival. Herb Caen, the famed city columnist of the San Francisco Chronicle and ‘the uncrowned prince’ of the city, reported in his daily column on Oct. 28 that his friend John Steinbeck had ‘chugged’ into town ‘from New York’ on the evening of Oct. 26.

“The next day local writer Curt Gentry got a tip from a Chronicle staffer. Doing what any hustling freelancer would do, Gentry called the famous visiting author in his hotel room and begged for an interview. Steinbeck was notoriously publicity shy, but he told Gentry to come to the St. Francis the next morning.

Doing what any hustling freelancer would do, Gentry called the famous visiting author in his hotel room and begged for an interview. Steinbeck was notoriously publicity shy, but he told Gentry to come to the St. Francis the next morning.

“Gentry, then 29, would go on to write more than a dozen books, including his biggest one with Vincent Bugliosi, Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders. But in 1960 he was a struggling writer, ex-newspaper reporter and bookstore manager. He lived in North Beach, the super-hip Italian neighborhood in downtown San Francisco. He mixed with jazz musicians, young writers and the Beats, who were headquartered at Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Bookstore at the corner of Broadway and Columbus. He knew Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsburg in passing and novelist/poet Richard Brautigan well, but Gentry was also a serious Steinbeck fan.

“On my research trip in the spring of 2010 Gentry met me at the Washington Square Bar & Grill. In its heyday the dim, aging, wood-lined North Beach landmark was a hangout for writers, politicos, musicians and the city’s in-crowd. But the WashBaG, as Herb Caen had nicknamed it, was almost empty when I was there and in a few months would close forever. Gentry, as well known to the staff as the owner, was easy to spot at the bar, looking dapper in his brown cap. He was the real deal. Helter Skelter made him rich. His 1991 New York Times bestseller J. Edgar Hoover exposed Hoover’s paranoia, his serial abuses of power and how he created the myth of the FBI as invincible and incorruptible.

Gentry, then 29, . . . mixed with jazz musicians, young writers and the Beats, who were headquartered at Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Bookstore at the corner of Broadway and Columbus. He knew Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsburg in passing and novelist/poet Richard Brautigan well, but Gentry was also a serious Steinbeck fan.

“At 79 Gentry was still writing tough books like the one he was working on about the Las Vegas mob. He couldn’t have been nicer, more helpful or more supportive of my Charley-retracing project. Not only did he buy me lunch and ignore our wide political divide. But he told me stories about the 1960 North Beach scene, repeated his favorite Steinbeck gossip and, when I expressed doubt about pulling off a book deal, kindly said, ‘I have faith in you.’

“On top of that moral support, Gentry gave me something else that was priceless – 10 pages of notes he had typed up after his meeting with Steinbeck. An observant record of what Steinbeck was doing and thinking in mid-Charley trip, Gentry’s account depicts a politically partisan 58-year-old at the top of his game, not lonely, not depressed, but full of piss and vinegar.

“When Gentry went to the St. Francis for his 11 a.m. interview, he said, Elaine was still in bed, Charley was in a kennel and John was hung over. ‘It looked like they both had quite a night,’ Gentry told me. A longtime admirer of Steinbeck, Gentry showed up at Steinbeck’s hotel suite with two shopping bags filled with every Steinbeck title he could carry – 21 books.

Gentry showed up at Steinbeck’s hotel suite with two shopping bags filled with every Steinbeck title he could carry – 21 books.

“He asked Steinbeck to sign the books, which he cheerfully did. Steinbeck had just finished sending Adlai Stevenson a telegram containing some silly anti-Nixon jokes and was sewing together the clasp for his walking stick. Later, after Steinbeck finished a rant about what he called the immorality of Americans, Gentry wrote that ‘he tossed the stick across the room in anger.’

“In his notes, Gentry described Steinbeck as friendly, talkative and animated. They discussed, among many subjects, the presidential election, what was wrong with America, why his friend and neighbor Dag Hammarskjold would make a great president and why Hemingway should write about people not bullfighting. Steinbeck told Gentry he was driving across the country in an attempt to find out what the American people thought about politics. ‘Everywhere he has traveled,’ Gentry wrote in his notes, ‘there is fantastic interest. People are not indifferent, or undecided. They just won’t say.’

“Telling Gentry he had lately been seeing signs of a close Kennedy victory, Steinbeck made fun of Eisenhower and bemoaned the fact that for the previous eight years the Republicans had ‘made it fashionable to be stupid.’ Gentry also noted that Steinbeck ‘had much to say on Richard Nixon, a great part of it unprintable.’ According to Gentry, Steinbeck was down on Americans for becoming soft and what he called ‘immoral.’ Previewing what he would express in his recently completed but not yet published novel The Winter of Our Discontent, Steinbeck defined immorality as ‘taking out more than you are willing to put back.’

Telling Gentry he had lately been seeing signs of a close Kennedy victory, Steinbeck made fun of Eisenhower and bemoaned the fact that for the previous eight years the Republicans had ‘made it fashionable to be stupid.’

“Steinbeck, wrote Gentry, ‘went on to note emphatically that “a nation or a group or an individual cannot survive immorality. The individual can’t survive being soft, comforted, content. He only survives well when the press is on him. In Rome when they began taking more out than they put in they began to decay.” And then his voice grew louder, his gestures became more emphatic as he added “If a fuse blew out in the Empire State Building today a million people would trample themselves to death . . . No one can do anything anymore. Who could slaughter and cut up a cow if they had to? No it has to be carefully cut for them, cellophane wrapped. They have lost the ability to be versatile. When either people or animals lose their versatility they become extinct.”‘

“When Gentry asked if he’d ever come back to live in California, Steinbeck said what he would later write in Travels with Charley after visiting his old haunts in Monterey. Steinbeck, according to Gentry, ‘said, sadly, “The truest words ever written were Thomas Wolfe’s ‘You Can’t Go Home Again.’ I wish it weren’t so but when I come back to California to stay it will be in a box.”‘

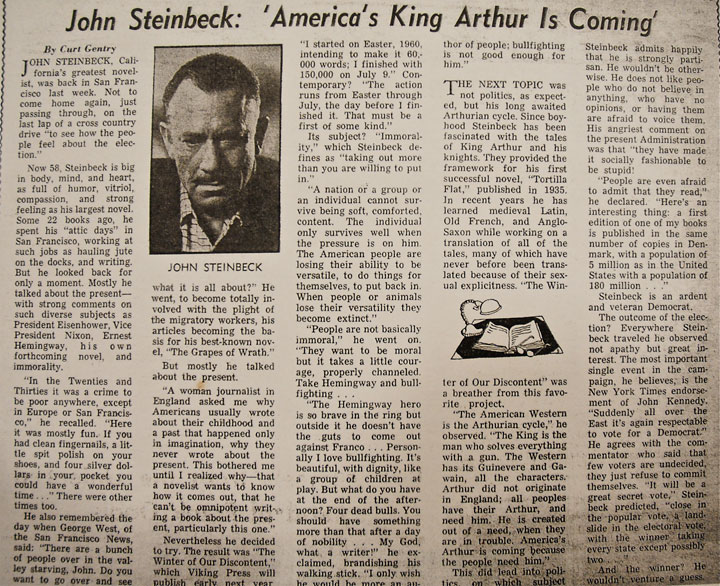

“Gentry had another gift for me. He gave me a copy of his original Steinbeck article, before it was edited. The piece ran in the San Francisco Chronicle on Sunday, Nov. 6, 1960, under the headline ‘John Steinbeck: “America’s King Arthur is Coming.”‘ (In an eerie presaging of Jackie Kennedy’s post-assassination comment that her husband’s presidency had been ‘an American Camelot,’ Steinbeck had said, apparently in reference to JFK, that all countries have legendary King Arthur-types who show up during times of trouble.)

Gentry had another gift for me. He gave me a copy of his original Steinbeck article, before it was edited.

“In his article Gentry described Steinbeck as ‘big in body, mind, and heart’ and ‘full of humor, vitriol, compassion and strong feeling.’ What Gentry had written was printed in the paper verbatim until it came to his attempts to share some of Steinbeck’s stronger political opinions with the Chronicle’s readers. A 500-word chunk at the end of his article containing all the mean things Steinbeck had said about Nixon and Eisenhower had been simply lopped off. The newspaper, which along with the San Francisco Examiner gave its editorial support to Nixon, wasn’t going to let a famous author trash its Republican hero two days before the election.

“The edits didn’t surprise Gentry. He was very involved in politics in 1960. Like Steinbeck, he was a devout Adlai Stevenson Democrat. During the 1956 presidential year, when he was active in the Young Californians for Stevenson, Gentry was called upon to drive Stevenson around town a couple times. He also was a driver for JFK, who apparently was on his best behavior because Gentry had no sexy story to share.

A 500-word chunk at the end of his article containing all the mean things Steinbeck had said about Nixon and Eisenhower had been simply lopped off. The newspaper, which along with the San Francisco Examiner gave its editorial support to Nixon, wasn’t going to let a famous author trash its Republican hero two days before the election.

“Gentry and Steinbeck kept in touch, exchanging several letters over the next few years. After Steinbeck’s death Gentry wanted to write a book about him and his relationship with his close friend Ed Ricketts, the marine biologist and real-life model for Doc in Cannery Row. Steinbeck’s agent, Elizabeth Otis, liked the idea, Gentry said. But widow Elaine – who controlled Steinbeck’s estate with a firm hand – nixed it. Elaine was, to put it kindly, not Gentry’s favorite Steinbeck. One thing that bothered him, he said, was the closeness of Elaine to Steinbeck’s biographers, Jackson Benson and Jay Parini.

“’They automatically accepted anything she said about his first two wives, Carol or Gwen,’ he said. ‘Everything I’ve read and heard is that Elaine was a real ball-buster and a terrible person, with her ex-husband, Zachary Scott (the movie actor), manipulating her in the background.’ That was a new bit of inside-Steinbeck World gossip/dirt for me. I had no idea if it was true and didn’t care one way or the other, but it sounded like something a guy who wrote an expose of J.E. Hoover might know.

“Since Gentry had lived almost exclusively in North Beach since the mid-1950s, he was a good person to ask about how the neighborhood had changed. The biggest difference, he said, was the proliferation of striptease joints. That was pretty much all the ‘entertainment’ there was in 2010. But in 1960, the clubs and bars spinning around the intersection of Columbus and Broadway were booking stars of the present and incubating stars of the future. Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Art Tatum played in clubs. Johnny Mathis got his start in North Beach in the mid ‘50s right after high school.

“The famous North Beach nightclub the Hungry i, by itself, is said to have launched the careers of Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl, Bill Cosby, Jonathan Winters and Barbra Streisand. The Hungry i was owned by mad impresario Enrico Banducci, who also opened up Enrico’s Coffee House on Broadway. Upstairs was Finochio’s, the famous nightclub featuring a vaudevillian floorshow of female impersonators. Gentry knew and liked Banducci. As soon as he made enough money, Gentry said, he basically lived in Enrico’s sidewalk cafe, which by day was a Herb Caen watering hole and by night a jazzy de facto after-hours club for cops, prostitutes and scuffling writers like him.

“Enrico’s Café, now closed, still existed in 2010. But its glory days, like North Beach’s, were ancient history. The afternoon I went to check it out it was closed for lunch. Basically unchanged since 1960, its outside tables were jammed inside behind big glass doors. The sidewalk patio was showing its age, its concrete cracked and its booths worn at the corners. The three-story building needed a paint job. The top floor where Finochio’s raunchy floorshow once shocked or entertained the straight world looked vacant.

Since Gentry had lived almost exclusively in North Beach since the mid-1950s, he was a good person to ask about how the neighborhood had changed. The biggest difference, he said, was the proliferation of striptease joints.

“Enrico’s Café’s near neighbors in 2010 were strip clubs like the Hungry I Club (‘The Best Girls in Town’) and Big Al’s adult bookstore. But still on the corner of Columbus and Broadway was City Lights Books, which became world famous in 1956 after its owner Lawrence Ferlinghetti published Allen Ginsberg’s poem ‘Howl.’ The precedent-setting First Amendment test-case that followed ultimately overturned the country’s obscenity laws and allowed banned books like Lady Chatterley’s Lover to be published in the Land of the Free.

“For several days in the fall of 1960 Steinbeck loafed only a few hundred feet from City Lights, yet he had nothing to do with the Beats and their revolutionary scene, and vice versa. Ferlinghetti’s assistant told me Ferlinghetti and Steinbeck – the new literary generation and the old – never met then or any other time. By 2010 City Lights and the Beat Museum – a well-done retail shrine to the lives and works of Kerouac, Ginsberg and other dead Beats – were the only two reasons left for going to what was once one of the coolest, most cutting edge, most culturally important intersections in America.”

Curt Gentry’s Book Blurb for Dogging Steinbeck

“I still believe John Steinbeck is one of America’s greatest writers and I still love Travels with Charley, be it fact or fiction or, as Bill Steigerwald doggedly proved, both. While I disagree with a number of Steigerwald’s conclusions, I don’t dispute his facts. He greatly broadened my understanding of Steinbeck the man and the author, particularly during his last years. And, whether Steigerwald intended it or not, in tracking down the original draft of Travels with Charley he made a significant contribution to Steinbeck’s legacy. Dogging Steinbeck is a good honest book.” – Curt Gentry

Photo of Curt Gentry by Jim Wilson courtesy San Francisco Chronicle. Excerpt from Dogging Steinbeck courtesy Bill Steigerwald.