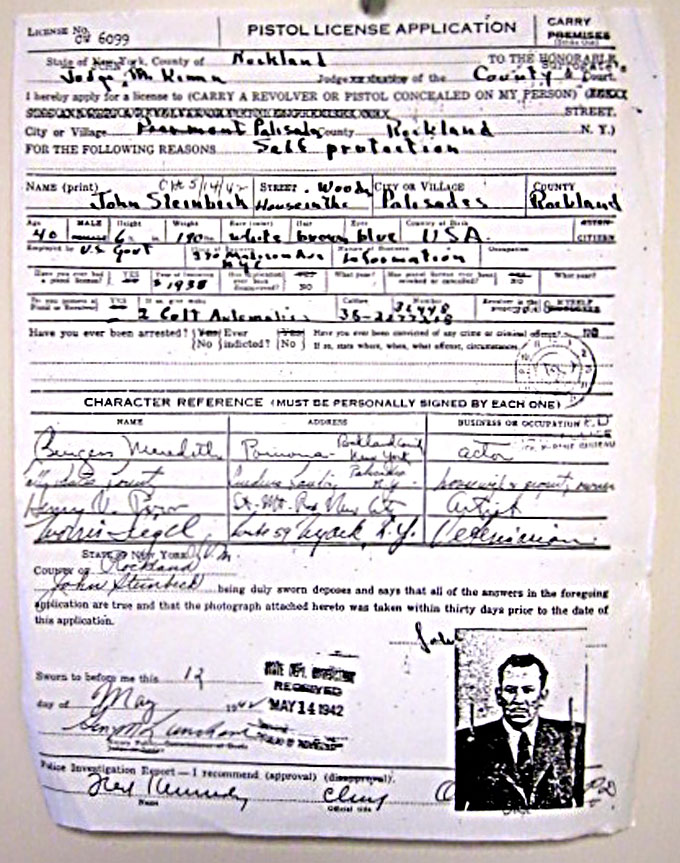

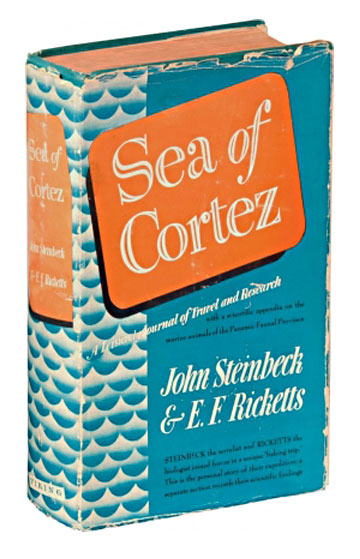

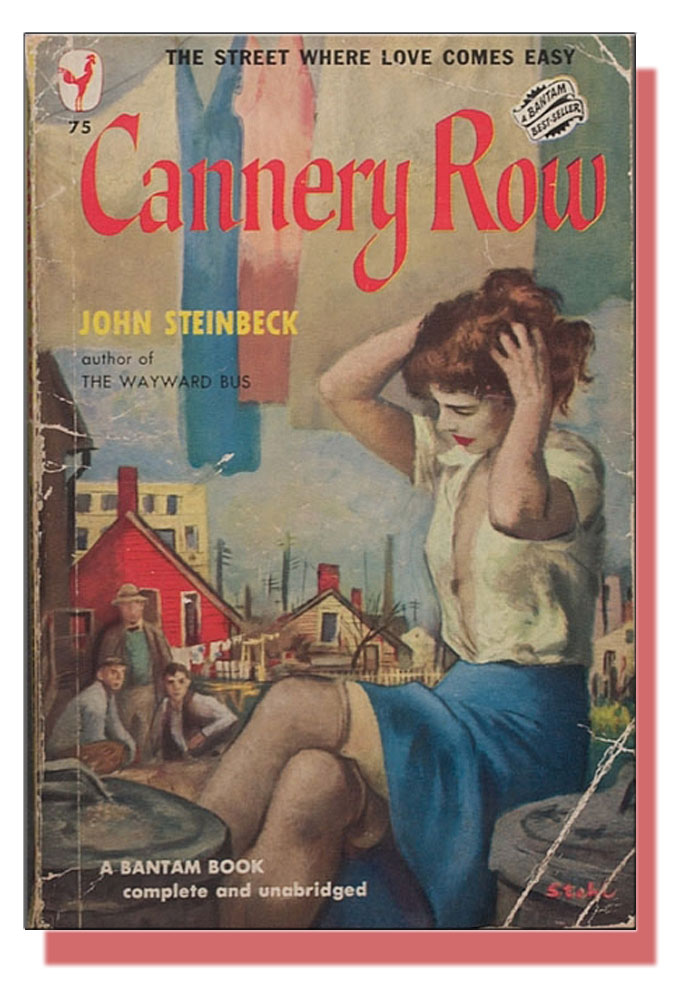

The film “Steinbeck: Armed with the Truth (And a Colt Automatic)” came about after Paul Boczkowski and Marie Wainscoat of Longtimers Productions, a California company, viewed a gallery exhibition I helped put together six or seven years ago in Pacific Grove with my wife Nancy and the prominent marine biologist Robert Brownell, a student of Ed Ricketts as well as John Steinbeck. The idea for the exhibition was born when a man sent me a copy of the application for a gun license that Steinbeck submitted in New York State on May 12, 1942. In his application Steinbeck sought permission to carry two concealed revolvers for “self-protection.”

New York State Gun License Fires Interest in Pacific Grove

The person who sent me the gun-license application worked for a museum and felt the application was important enough to be made public. The subject of Steinbeck and guns already had my attention, and I agreed. Some years earlier I had spoken with a Salinas woman who told me that sometime in the mid-to-late 1930s she had witnessed Steinbeck being threatened by a man with a gun, perhaps hired by others, who was upset about what he felt Steinbeck was writing. We called the exhibition—which included artwork, letters, and documentation—“Steinbeck: Armed with the Truth (And a Colt Automatic).” The producers kept the title for their film about the show. “Steinbeck Fully Loaded,” a Sunday magazine feature, appeared in the Monterey County Herald.

I also wrote a piece about Steinbeck’s gun license application for an innovative literary-blog website called Red Room that, unfortunately, no longer exists. Before the site went out of business, Paul Douglass—at that time the editor of Steinbeck Review—picked up on my post. This led to my writing a pair of articles for the journal in the spring of 2008 and the fall of 2009.

Since that time, my account of Steinbeck and guns has appeared in a number of periodicals and books, though no one bothers to notify me before they publish it. The gun license episode tied in with other stories and historic tidbits about Steinbeck I had picked up while writing for the Monterey County Herald, operating a Pacific Grove art gallery with a literary bent, and co-curating the inaugural art exhibition at the National Steinbeck Center in 1998.

Monterey County Sources Inspire Stories About Steinbeck

My sources were often people who had known Steinbeck well, or their descendants. Two were classmates of John in Salinas. Another was the daughter of a Monterey County cop who corresponded with Steinbeck after the writer left California for New York, and who shipped Steinbeck several revolvers via railway express. A fourth was the son of a Monterey County Herald editor who became a good friend to Steinbeck and helped him find a Big Sur mountain lion as a gift for the people of England—an incident I used in a book of stories that I wrote about Steinbeck’s life in Monterey County and New York State.

I call the series “Almost True Stories from a Writer’s Life.” The stories reflect the portrait of Steinbeck painted by my sources: a complex man of great gifts, deep compassion, and capacity for fun, traits overshadowed by very real and very dark threats experienced by Steinbeck in Monterey County. Some of my stories include artists, the secondary theme of the film. Artists were important to Steinbeck throughout his lifetime: he numbered them among his friends and felt not only comfortable, but also safe with them. When you have as many enemies as Steinbeck did, I learned, “safe” becomes important.

Which is why he applied for that gun license on May 12, 1942.

Sample “Almost True Stories from a Writer’s Life” in Steve Hauk’s Archive.—Ed,