If you keep an open mind about astrology, as I’ve done in my investigation and application of its principles, you can learn quite a bit about John Steinbeck from his horoscope wheel. I know: reading astrology charts seems unusual for an electronic technician like me. Frankly, I was skeptical about the subject when I started—until I read the works Carl Jung and followers of the pioneering Swiss psychologist who fell out with his former mentor, Sigmund Freud. Steinbeck, who distinctly disliked Freud’s ideas about human sexuality and neurosis, was deeply attracted to Jung’s insights into human consciousness and imagination. Jung’s influence on Steinbeck is particularly compelling in Sea of Cortez, the record of Steinbeck’s expedition to Baja, California with Ed Ricketts 75 years ago.

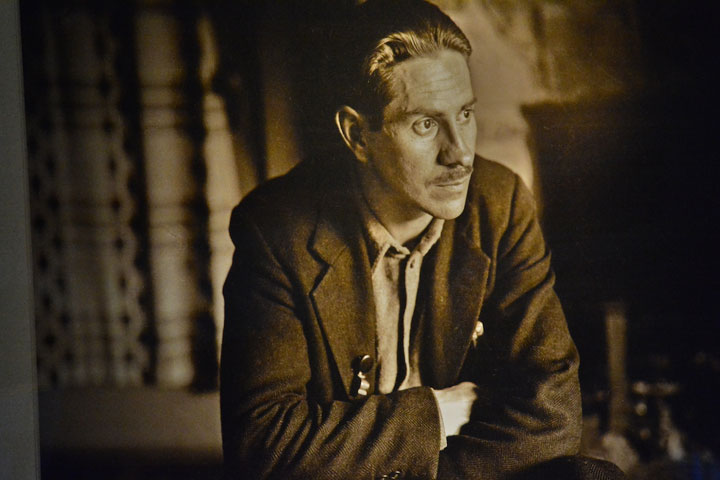

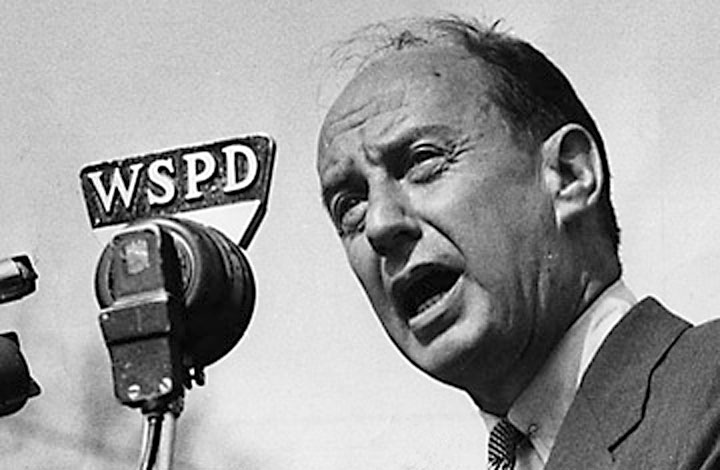

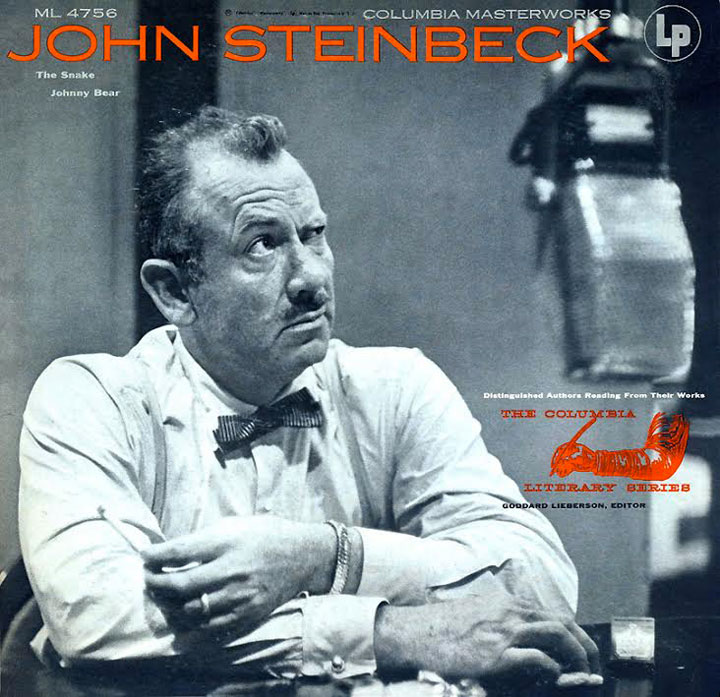

John Steinbeck, who distinctly disliked Sigmund Freud’s ideas about human sexuality and neurosis, was deeply attracted to Carl Jung’s insights into human consciousness and imagination.

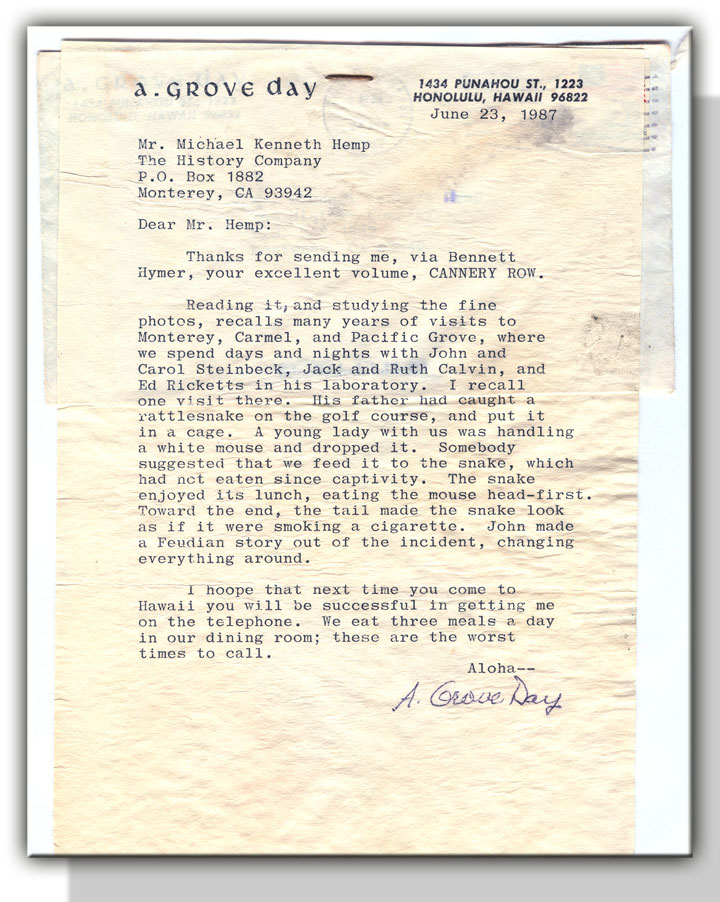

Steinbeck may have encountered Jung’s writing as early as 1922 while a student at Stanford, where he read philosophy and psychology along with other subjects that appealed to his needs as a writer. By the time he met Ed Ricketts and Joseph Campbell 10 years later, Jung had attracted the attention of these important figures in Steinbeck’s life as well. Sea of Cortez, written with Ricketts in 1941, bursts with Jungian ideas—such as the closely related concepts of synchronicity, acausality, and non-teleology—that get almost as much space as the ecology of the marine invertebrates and the culture of the people that Ricketts and Steinbeck observed along the way.

Carl Jung, Synchronicity, and Astrology Charts

I began my study of Carl Jung in 1965 and, three years later, astrology as part of a college assignment in which I intended to disprove astrology’s scientific validity. In my profession as an electronic technician at RCA’s Astro Electronic Division, I investigated further, mostly out of curiosity, but also out of respect for Jung’s rigorous empiricism. As a physician trained in the German tradition, he insisted on assembling evidence before expounding theory when he wrote about the personality, the unconscious, and the possibility that astrology had scientific value after all.

Jung insisted on assembling evidence before expounding theory when he wrote about the personality, the unconscious, and the possibility that astrology had scientific value after all.

I was three years into my study of Jung when I read “Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle,” where he endorses astrology as a tool in treating psychiatric patients. To be honest, the notion angered me so much I stopped reading his work until I renewed my research on astrology in an attempt to demonstrate, scientifically, why it really wasn’t worth the time. My method was simple: do as many horoscope readings as possible, then compare astrology chart results with what I learned from interviewing the individuals I had charted. I did dozens of charts and interviews and found much to discount and dismiss. But I also turned up evidence that, to my surprise, supported Jung’s claims about astrology.

I did dozens of charts and interviews and found much to discount and dismiss. But I also turned up evidence that, to my surprise, supported Jung’s claims about astrology.

During the same period I encountered the works of Dane Rudhyar, a long-lived and multi-talented follower of Carl Jung, born in Paris, who composed modernist music, practiced a form of humanistic astrology, and died in San Francisco in 1985. Discovering Rudhyar was a watershed moment in my study of Jung and astrology, and Rudhyar’s writing still influences me in my thinking and practice today. By reading Rudhyar, Marc Edmund Jones, and other writers on the subject, I learned about the influence of the astrological signs, the planets and houses, and what astrologists call angular relationships in our lives.

During the same period I encountered the works of Dane Rudhyar, a long-lived and multi-talented follower of Carl Jung, born in Paris, who composed modernist music, practiced a form of humanistic astrology, and died in San Francisco in 1985. Discovering Rudhyar was a watershed moment in my study of Jung and astrology, and Rudhyar’s writing still influences me in my thinking and practice today. By reading Rudhyar, Marc Edmund Jones, and other writers on the subject, I learned about the influence of the astrological signs, the planets and houses, and what astrologists call angular relationships in our lives.

John Steinbeck, Ed Ricketts, and Sea of Cortez

I’m a practical, intuitive type, and I found interpreting chart patterns and relationships, in both their static and dynamic senses, fascinating. Probably for the same reason, I also enjoyed the fiction of John Steinbeck. What I learned from Carl Jung’s “Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche,” “Psychological Types,” and “Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle” clarified my understanding of Steinbeck and Ricketts’s holistic, non-teleological thinking in Sea of Cortez, Steinbeck’s most thoughtful work of non-fiction.

What I learned from Carl Jung’s ‘Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche,’ ‘Psychological Types,’ and ‘Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle’ clarified my understanding of Steinbeck and Ricketts’s holistic, non-teleological thinking in ‘Sea of Cortez.’

As I read astrology charts and applied what I was learning, Ricketts and Steinbeck’s perceptions helped hone my technique and increase my skill. In my business, I was discovering the truth of Carl Jung’s belief that “Astrology is assured of recognition from psychology without further restrictions,” that it “represents the summation of all the psychological knowledge of antiquity.” Jung explained why he believed this was so: “The fact that it is possible to construct a person’s characters from the data of his nativity shows the validity of astrology. I have often found that in cases of difficult psychological diagnosis, astrological data elucidated points which I otherwise would have been unable to understand.” Astrology, said Jung, could be shown empirically to be scientific, “a large-scale example of synchronicity if it had at its disposal thoroughly tested findings.”

What John Steinbeck’s Astrological Chart Reveals

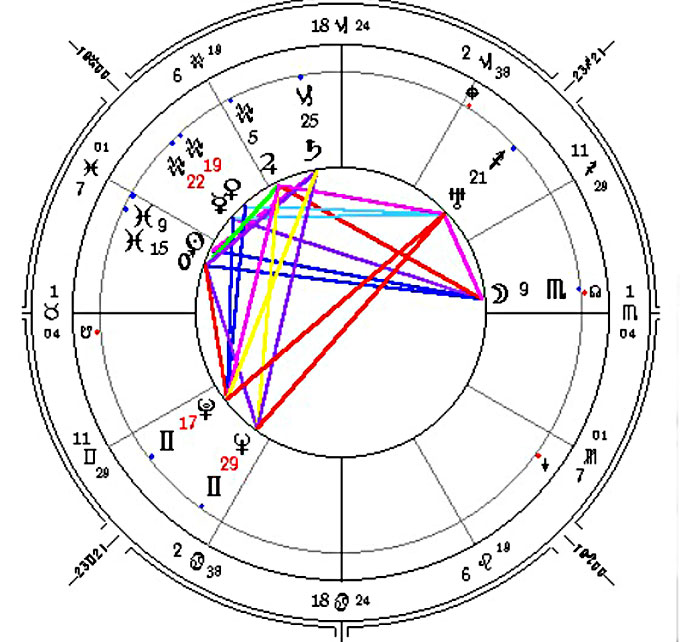

What can we learn from interpreting John Steinbeck’s astrological wheel chart, shown here?

To start with, the most influential part of anyone’s horoscope chart is the Sun, the key element in life. For example, when we say we’re a Virgo, Leo, or Aquarius, we mean that the Sun was in that particular astrological sign or constellation at the moment of our birth. Based on the location of the Sun sign when John Steinbeck—a Pisces—was born, it’s clear that Steinbeck was an Introverted Sensation Type with a Thinking auxiliary in his psychological make-up. Sensation as the primary function naturally made him more perceptive than judgmental—a helpful profile for the non-teleological exploration of human behavior demonstrated in Sea of Cortez and in his fiction.

Sensation as the primary function naturally made Steinbeck more perceptive than judgmental—a helpful profile for the non-teleological exploration of human behavior demonstrated in ‘Sea of Cortez’ and in his fiction.

Practically speaking, this means that when Steinbeck considered a situation, all the information he gathered through observation and experience went from the source—what he actually sensed—into his imaginative unconscious. There it was shaped and modified by his fears, hopes, desires, and prejudices before becoming conscious in his mind or relating to his emerging Ego.

When Steinbeck considered a situation, all the information he gathered through observation and experience went from the source—what he actually sensed—into his imaginative unconscious.

As Steinbeck and Ricketts suggest in the long philosophical passages that make Sea of Cortez fascinating to readers like me (and perplexing to others), one goal of what they call non-teleological thinking is to reduce the unconscious influence and stick as closely as possible to the reality of the object being perceived. In this connection, introverts rely on internal, subjective, and experienced evidence, seeing the world in themselves. Extraverts, by contrast, judge their perceptions based upon external evidence, seeing themselves in the world. Though it’s a bit of an over-simplification, it seems fair to say that John Steinbeck was an introvert with extraordinarily acute perception about human character and behavior.

As Steinbeck and Ricketts suggest in the long philosophical passages that make Sea of Cortez fascinating to readers like me (and perplexing to others), one goal of what they call non-teleological thinking is to reduce the unconscious influence and stick as closely as possible to the reality of the object being perceived. In this connection, introverts rely on internal, subjective, and experienced evidence, seeing the world in themselves. Extraverts, by contrast, judge their perceptions based upon external evidence, seeing themselves in the world. Though it’s a bit of an over-simplification, it seems fair to say that John Steinbeck was an introvert with extraordinarily acute perception about human character and behavior.

Though it’s a bit of an over-simplification, it seems fair to say that John Steinbeck was an introvert with extraordinarily acute perception about human character and behavior.

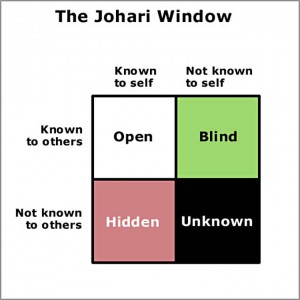

In the humanistic astrology of Dane Rudhyar and others, the Sun’s location in an individual’s astrology chart reveals the Self, the Soul, at the center of the psyche. This Self can be described as having three major components in the terminology developed by Carl Jung: the personality or persona, the Ego, and the Unconscious. Using the Johari Window, we can visualize these three components. The persona is represented by the “Open” and “Blind” panes. The “Blind” pane signifies the parts of our Ego that others see in us but about which we are unaware. The “Hidden” window includes those parts of our Ego that we recognize but do not wish them to see. In a horoscope wheel chart, the Sign and Degree of the cusp of the First House (the line between the 12th House and the 1st House, usually at nine o’clock) represents the way an individual projects to or is perceived by others: his or her “persona.”

In the humanistic astrology of Dane Rudhyar and others, the Sun’s location in an individual’s astrology chart reveals the Self, the Soul, at the center of the psyche. This Self can be described as having three major components in the terminology developed by Carl Jung: the personality or persona, the Ego, and the Unconscious. Using the Johari Window, we can visualize these three components. The persona is represented by the “Open” and “Blind” panes. The “Blind” pane signifies the parts of our Ego that others see in us but about which we are unaware. The “Hidden” window includes those parts of our Ego that we recognize but do not wish them to see. In a horoscope wheel chart, the Sign and Degree of the cusp of the First House (the line between the 12th House and the 1st House, usually at nine o’clock) represents the way an individual projects to or is perceived by others: his or her “persona.”

In a horoscope wheel chart, the Sign and Degree of the cusp of the First House represents the way an individual projects to or is perceived by others: his or her ‘persona.’

All this suggests that how a person projects himself or herself may mask the real individual, often quite dramatically. So it’s important to remember that we are partially—sometimes significantly—responsible for the opinions others have about us: we unconsciously project our own qualities into the perceptual image those around us, coloring and frequently complicating our relationships. The influence of the Sun may be masked within the persona, and often we are responsible for the mask. Consider Carl Jung’s archetypal concept of Shadow, for instance. In Jungian terms, our life experiences provide growth lessons along a path between the image we project, our Ego, and who we actually are as defined by the sign degree of our Sun.

In Jungian terms, our life experiences provide growth lessons along a path between the image we project, our Ego, and who we actually are as defined by the sign degree of our Sun.

Humanistic astrologers recognize this truth: our journey through life includes challenges that cause the persona as defined by the qualities represented in our Ascendant to join the Ego and more closely align with the Sun or Self. As Jung suggests when discussing the Shadow, this makes the journey especially difficult when it challenges the perceptions of those closest to us and can create interpersonal problems with perfect strangers. These were issues for John Steinbeck throughout his life.

As Jung suggests when discussing the Shadow, this can create interpersonal problems with perfect strangers. These were issues for John Steinbeck throughout his life.

Steinbeck’s Ascendant is at 1 degree 4 minutes Taurus, significant because it increased the likelihood of his compatibility with Ed Ricketts, who had a Taurus Sun. Given what I’ve learned about Taurus Ascendants, I suspect that Steinbeck, with a Pisces Sun, was sometimes judged by others to be more predictable than he really was. On first meeting, his personality would have attracted someone like his wife Carol, who also had a Pisces Sun. A woman of her perceptiveness would have tacitly understood her need for a partner with stability, and when they met Steinbeck’s persona could have been mistaken for that of a Taurus. Steinbeck, with a Taurus Ascendant, would offer such an illusion.

Steinbeck’s Taurus Ascendant is significant because it increased the likelihood of his compatibility with Ed Ricketts, who had a Taurus Sun.

Most importantly, John Steinbeck’s horoscope wheel reveals a significant pattern formed by the location of planets in Sign and Houses. The majority of planets in his astrology chart are in the upper left quarter, an area that is associated with objective social types. Steinbeck’s avowed goal as a writer was social: to observe others, increase understanding, and influence change—a purpose that history has proven he met beyond anyone’s expectations, including his own. For readers today, this may be the most important lesson to be learned from John Steinbeck’s astrology chart, his understanding of Carl Jung, and his collaboration with Ed Ricketts in writing Sea of Cortez, a gift from the tide pool and the stars.

The author welcomes inquiries at wstillwagon1@earthlink.net.—Ed.