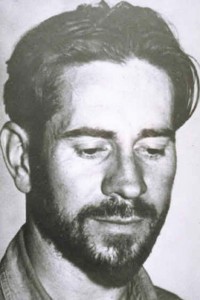

Like John Steinbeck, the writer’s friend Ed Ricketts was reared in the Episcopal Church, a coincidence of some importance. Described in Cannery Row as “half satyr, half Christ,” “Doc” Ricketts inspired the creation of identifiably Doc-like characters in works of fiction written by Steinbeck over two decades, including In Dubious Battle and Sweet Thursday. The friendship with Ricketts was fundamental to Steinbeck’s thinking through the 1930s and 40s, and the Bay of California scientific expedition undertaken by the men in 1940 produced Sea of Cortez,

Like John Steinbeck, the writer’s friend Ed Ricketts was reared in the Episcopal Church, a coincidence of some importance. Described in Cannery Row as “half satyr, half Christ,” “Doc” Ricketts inspired the creation of identifiably Doc-like characters in works of fiction written by Steinbeck over two decades, including In Dubious Battle and Sweet Thursday. The friendship with Ricketts was fundamental to Steinbeck’s thinking through the 1930s and 40s, and the Bay of California scientific expedition undertaken by the men in 1940 produced Sea of Cortez, a collaborative meditation on the meaning of life that reaches an emotional peak on Easter morning in a passage foreshadowing The Winter of Our Discontent, a later Holy Week narrative with an Episcopal church setting.

Intimate Lives That Included Episcopal Church Training

Reared in Chicago, Ed Ricketts—like Steinbeck—attended Episcopal church services as a boy and received Christian training in Episcopal church Sunday school and confirmation classes. Intelligent, introspective, and independent-minded college dropouts, both men outgrew Episcopal Church teaching as adults, becoming skeptical about religion, passionate about science, and unconventional in behavior. When they met in 1930, Ricketts was running a biological-specimen business in Pacific Grove, California, and working on a pioneering textbook of coastal ecology eventually published by Stanford University. Steinbeck, recently married and undiscovered as a writer, was younger and less sophisticated. As he noted in his profile of Ricketts years later, Steinbeck learned deeply about many subjects, including music, from the man with whom he shared a deep personal connection based in part on shared experience in the Episcopal Church.

Reared in Chicago, Ed Ricketts—like Steinbeck—attended Episcopal church services as a boy and received Christian training in Episcopal church Sunday school and confirmation classes.

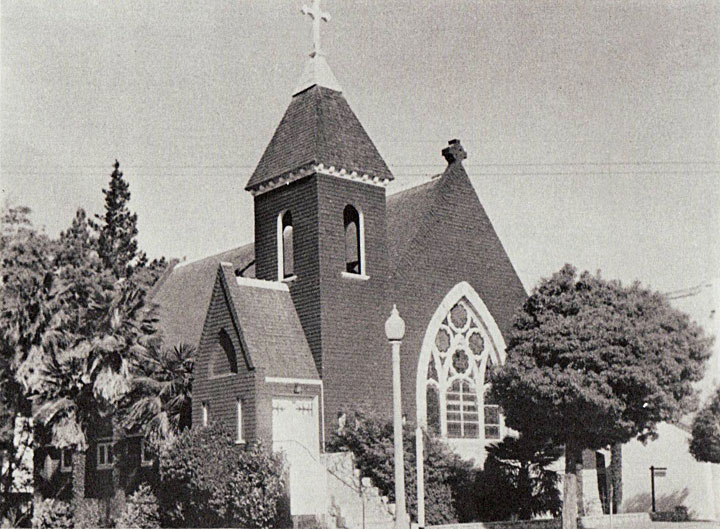

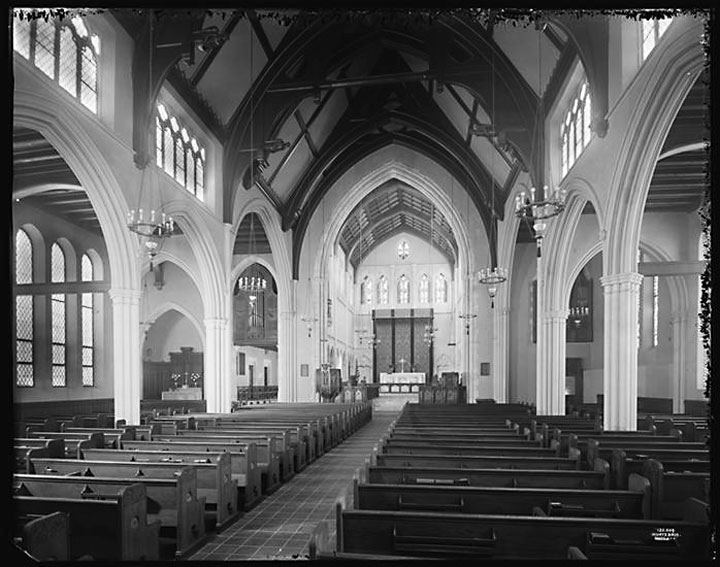

Their surviving letters demonstrate the intimacy of their relationship and their familiarity with Episcopal church doctrine, custom, and culture. Writing to Steinbeck in 1946, for example, Ricketts reflected with characteristic irony and humor on his mother’s recent death: “Directly after mother was taken very sick, she wanted an Episcopal priest. Terribly unfortunate that a few months before this, the satyr [in him] caught up with him again. . . . The wicked old women, of the church that was founded by charitable Christ, turned on him viciously.” The parish in question was All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Carmel, the same Episcopal church where Steinbeck served as the godfather for his sister Mary’s younger daughter in 1935.

‘The wicked old women, of the church that was founded by charitable Christ, turned on him viciously.’

As a result of the clerical misbehavior detailed in the letter, Ricketts’ dying mother was visited by the rector of St.-Mary’s-by-the-Sea Episcopal Church in Pacific Grove, the same Episcopal church where Thom Steinbeck, the author’s son, would be married 50 years later. The Steinbeck family cottage where the writer and his wife were living when Ricketts and Steinbeck first met—and to which Steinbeck retreated when Ricketts died—is located only two blocks from St. Mary’s Episcopal Church. Both literally and figuratively, the Episcopal Church loomed over the lives of John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts—the man he called his soul mate—from the beginning to the end of their intimate, intriguing relationship.

Photo by Bryant Fitch (October 1939) http://www.caviews.com/ed.htm