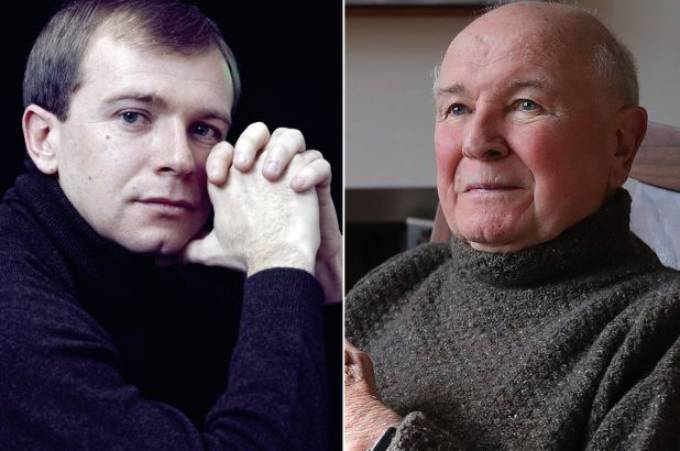

Although Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck won’t be released until October 13, a pair of publications with literary reach have picked William Souder’s scholarly new Steinbeck biography out of their fall lineup in previews that bode well for the book’s reception by readers. Writing in the September 24 New York Times, Joumana Khatib praised the balance, scope, and timeliness of the first full-length life of John Steinbeck to appear in a generation:

A comprehensive new biography of America’s best-known novelist of the Great Depression arrives at a timely moment. Though Steinbeck’s books remain his most significant literary output, Souder also dives into Steinbeck’s life as a journalist, including overseas postings during World War II and the Vietnam War, and how they shaped his worldview. And he doesn’t shy away from Steinbeck’s vices — philandering, heavy drinking — along with the feelings of inferiority that haunted him throughout his career.

A Life for Our Time of “the Novelist for Our Time”

In an October 2020 Bookpage.com feature post, reviewer Harry L. Carrigan agreed with Khatib’s assessment. “John Steinbeck just might be the novelist for our time,” Carrigan concluded, and “as vibrantly illuminated by Mad at the World,” Steinbeck’s reputation for relevance is rooted in a pair of works he said he felt compelled to write as a warning to his sons and country:

In his sprawling epic The Grapes of Wrath, he captured Americans’ peculiar yearning for a life not their own, the promise of wealth beyond the veil of desolation and the wretched impossibility of such a promise. Steinbeck’s other epic, East of Eden, illustrates the ragged desperation of human nature, wreaking destruction rather than carrying hope. William Souder’s bracing Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck vividly portrays the brooding and moody writer who could never stop writing and who never fit comfortably into the society in which he lived.