Hard news from three different sources suggests the year ahead will be a busy one for followers, fans, heirs, and collectors of John Steinbeck. Steinbeck at Stanford is the subject of a special January 30 library event at Stanford University (sold-out as of this writing) that includes a lecture by Stanford professor Gavin Jones and an exhibit of items from Stanford’s substantial collection of Steinbeck editions, manuscripts, and memorabilia. Hard on the heels of October’s sale of manuscripts and personal possessions from the estate of Steinbeck’s widow Elaine, by an auction house in San Francisco, New Jersey’s Curated Estates auction service has announced the sale of items—including Steinbeck’s baby hair and confirmation certificate—timed to end on February 27, the author’s birthday. As reported by the Hollywood Reporter, attorneys for the widow of Steinbeck’s son Thom are taking their case for reassigning the movie rights to Steinbeck’s books all the way to the Supreme Court, assuming the high court finds time for issues beyond impeachment and tax returns in the busy year ahead.

Hard News Forecasts Busy Year Ahead for Followers, Fans of John Steinbeck

Fall 2019 Steinbeck Review Reconsiders John Steinbeck

The Fall 2019 issue of the journal Steinbeck Review, a biannual publication of Penn State Press in cooperation with the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University, is now available online and in print. Contents include essays on aspects of John Steinbeck’s life and work as a proto-ecologist and internationalist viewed from a contemporary perspective; the publishing history of Steinbeck’s books in the former Iron Curtain countries of Eastern Europe; and the challenges of teaching Steinbeck to students who may be better versed in the #MeToo movement than the progressive labor movement that preoccupied Steinbeck’s interest and writing in the 1930s. Also included in the Fall 2019 issue are book reviews, announcements, and a summary of Steinbeck news since the summer.

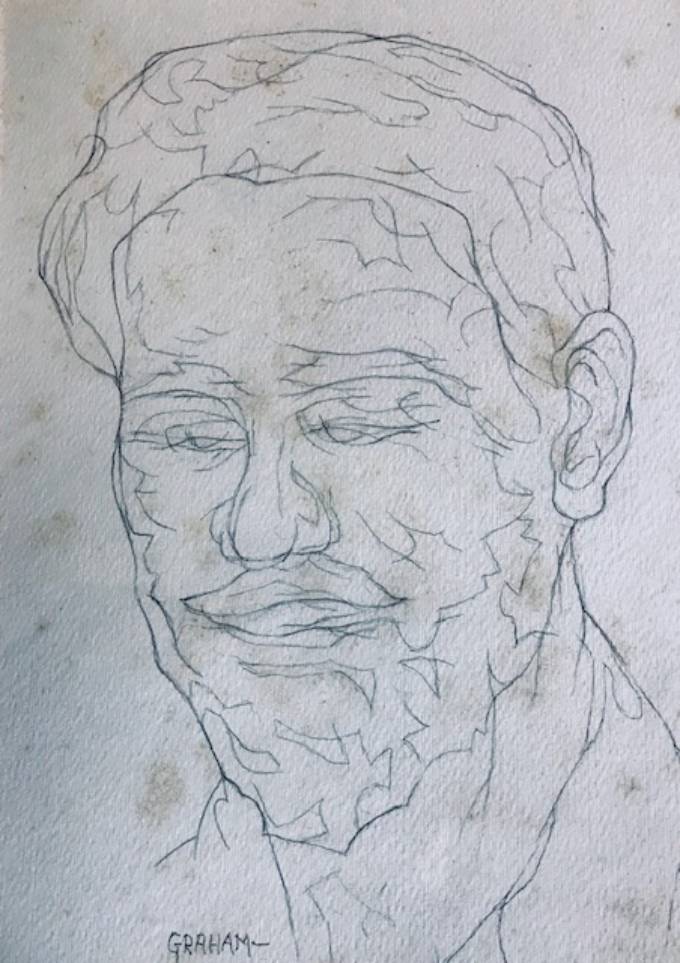

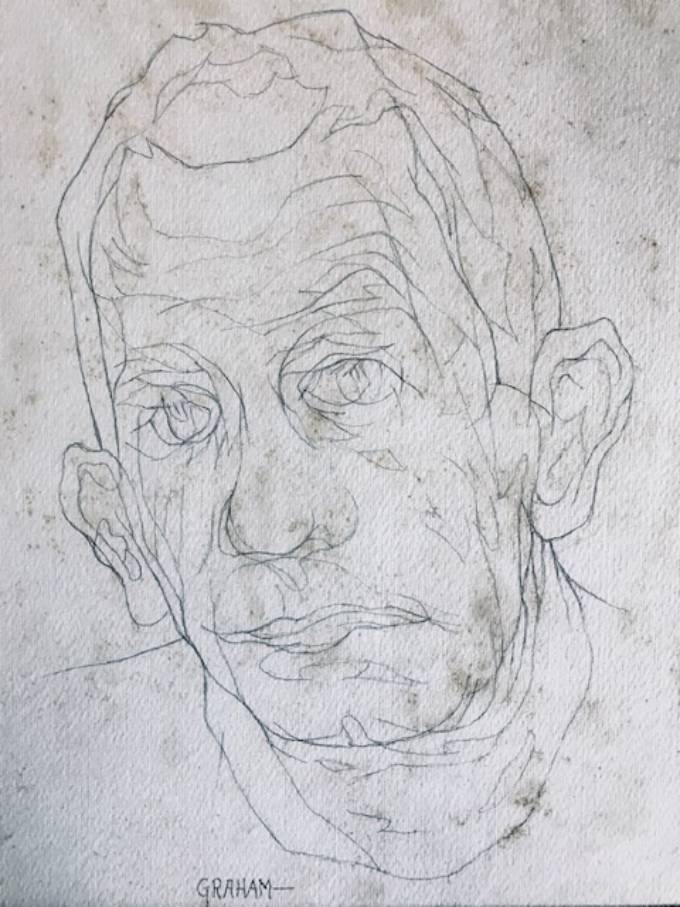

Sketches of John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts Resurface in Carmel, California Collection

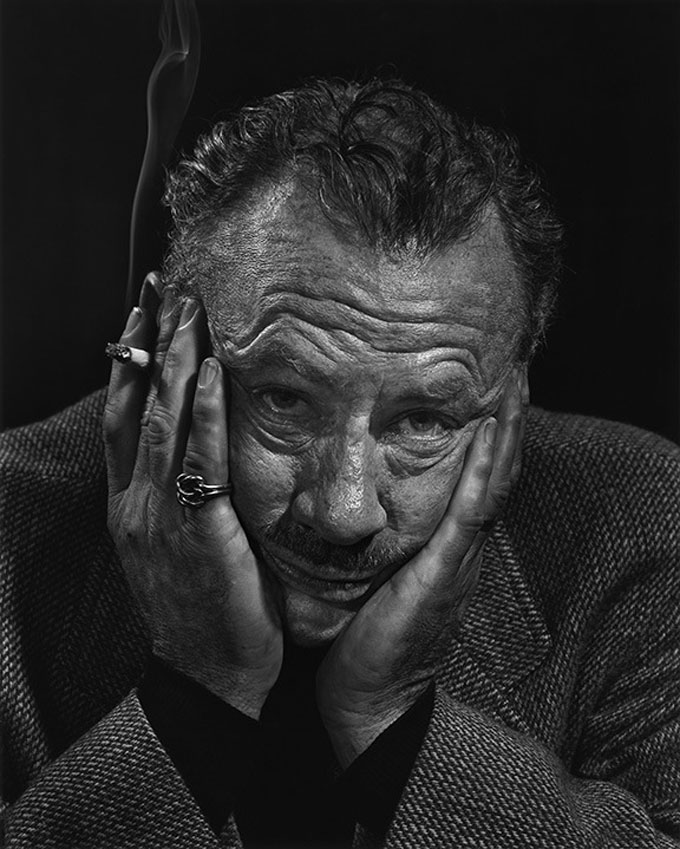

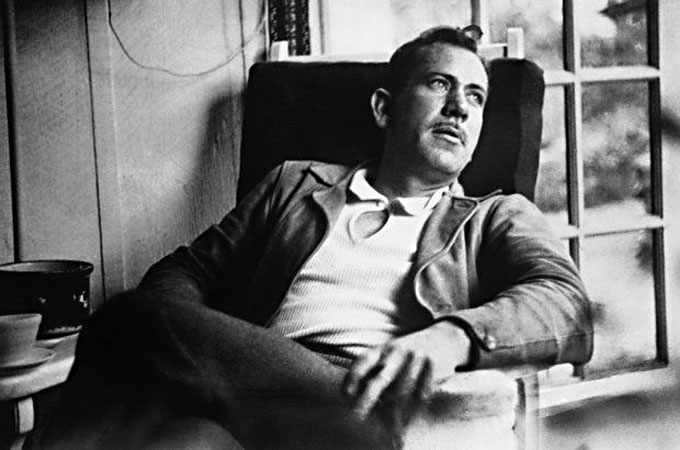

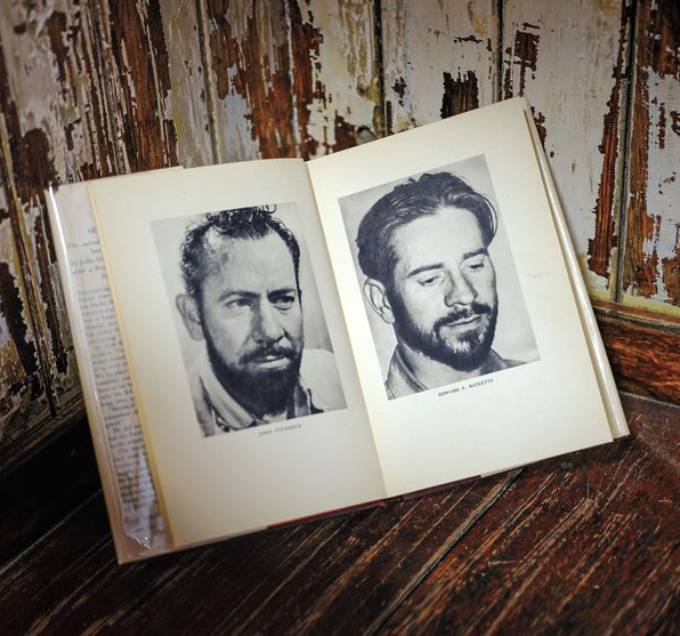

Numerous artists drew, painted, or photographed John Steinbeck, but artistic images of his friend Ed Ricketts are relatively rare. This made the chance discovery of a drawing of Ricketts by Ellwood Graham—in a Carmel, California art collection that also includes Graham’s sketch of Steinbeck—especially exciting. Both drawings are discolored and have acid burn, but Graham’s lines are vivid and the impression in both, even before restoration, remains strong.

In 1991 Graham penned his remembrance of doing the two drawings (shown here) around 1940-41, and in 1995 they were included in a Monterey Museum of Art exhibition, curated by Richard Gadd and called “Monterey Life: The Steinbeck Years.” Ironically, when I came across the pair on my first visit to a Carmel collector’s home several months ago I was writing The Willow Grave, a screenplay on Graham and his wife Judith Deim. Ricketts and Steinbeck are significant characters in the story.

“Doing John’s Portrait Was an Unusual Luxury” for Artist

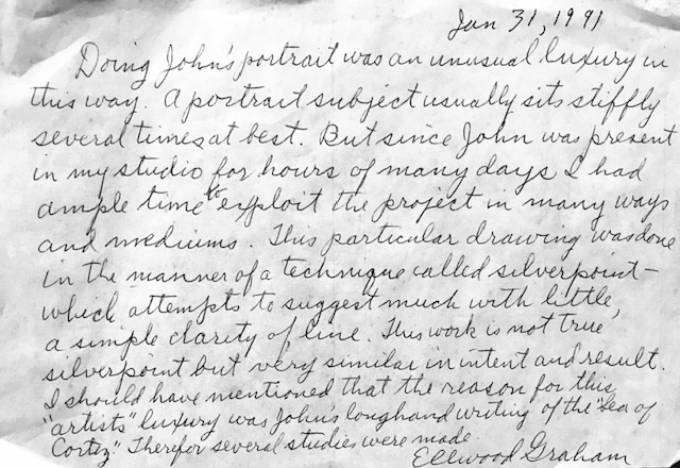

Graham’s recollection of sketching Steinbeck was still fresh when he wrote this note:

Doing John’s portrait was an unusual luxury in this way. A portrait subject usually sits stiffly several times at best. But since John was present in my studio for hours of many days, I had ample time to exploit the project in many ways and mediums. This particular drawing was done in the manner of a technique called silverpoint – which attempts to suggest much with little, a simple clarity of line. This work is not true silverpoint but very similar in intent and result. I should have mentioned that the reason for this “artists” luxury was John’s longhand writing of “The Sea of Cortez.” Therefor several studies were made.

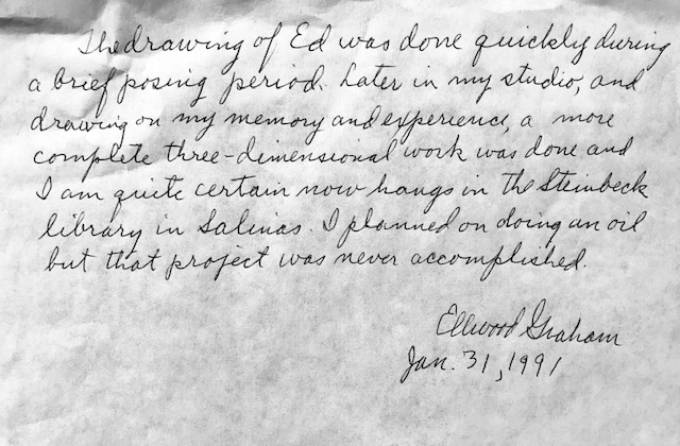

Equally strong was Graham’s memory of sketching Ricketts:

The drawing of Ed was done quickly during a brief posing period. Later in my studio, and drawing on my memory and experience, a more complete three-dimensional work was done and I am quite certain hangs in the Steinbeck library in Salinas. I planned on doing an oil but that project was never accomplished.

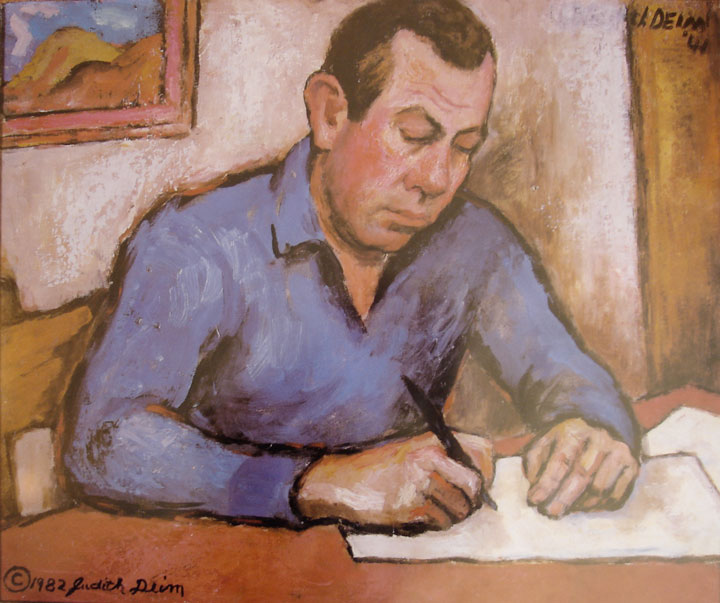

Ellwood Graham and Judith Deim—then going by her given name of Barbara Stevenson—were artists from St. Louis, Missouri, who made their way to California on Route 66 during the Dust Bowl days of the Great Depression. By chance in Los Angeles they met Gordon Grant, the California artist who was creating murals under the auspices of the Federal Art Project, and he hired them. They were working on the mural in the Ventura, California post office when—again a chance meeting—they met Steinbeck and Ricketts, who were passing through on their way to Mexico. Before parting, Ricketts and Steinbeck invited the young artists to visit Monterey, which, of course, they eventually did. Deim was to do her own portrait of Steinbeck (shown here). It is in the collection of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies. Graham also did an oil portrait of the writer, but it was lost and its whereabouts are unknown.

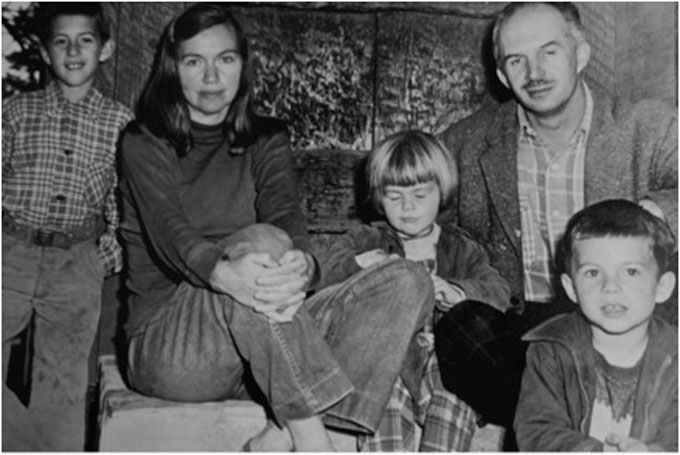

Newlyweds, Deim and Graham (shown with their children in this undated photo) met as students in the School of Fine Arts at Washington University and went on to distinguished careers in California and Mexicao. Deim exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Art, the Palace of the Legion of Honor, and the Patzcuaro Museum (she spent the last years of her life in Mexico’s Michoacan). Among many honors, she was the first artist given a solo exhibition at the Carmel Art Association, in 1946. Graham has work in the Whitney Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the De Young Museum, and the Monterey Museum of Art. Among dozens of exhibits and solos, he had work in the 1939 Golden Gate International Exhibition in San Francisco. Deim spent her last years in Mexico. Graham died in Oregon.

An art dealer in Los Angeles who specializes in early modernism told me he knew Graham had a strong sense of his worth as an artist, “because when I find his old paintings, they usually have a pretty high price—for the time—on the reverse side.” Steinbeck and Ricketts believed in Graham and Deim’s talent; Steinbeck, for instance, felt easy enough in their presence to write while they painted him. Luck brought Graham and Deim to the attention of Gordon Grant in Los Angeles and Ricketts and Steinbeck at the Ventura post office. I, too, was fortunate to happen upon Ellwood Graham’s drawings in that Carmel collection.

Ellwood Graham’s recently rediscovered sketches of John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts courtesy of private collector in Carmel, California.

John Steinbeck Sale Another Reminder of Missing History

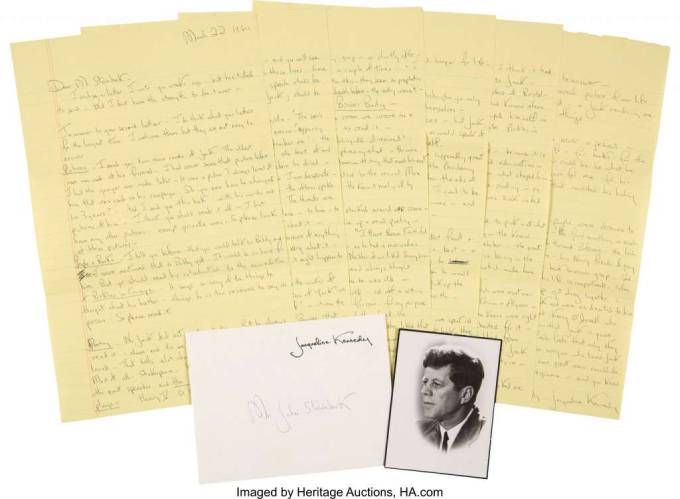

Like the recent donation of the S.J. Neighbors collection of John Steinbeck papers to Stanford University, the upcoming sale of John Steinbeck memorabilia by Heritage Auction House in San Francisco serves as a reminder that much remains to be learned about the author’s life and work—and that access to documents is key to discovery. Among the 36 items on offer, spanning 100 years of Steinbeck family history, are the walnut box Steinbeck’s grandfather gave his grandmother, an early manuscript of his novel Tortilla Flat, and the journal he kept when he was writing The Wayward Bus. Also included are letters from President John Kennedy and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, the latter in response to questions posed to her by Steinbeck for the biography she asked him to write following her husband’s assassination in 1963. “I enclose a letter I wrote you weeks ago – but hesitated to send. But I don’t have the strength to do it over. In answer to your second letter – I do think about your letters for the longest time. I welcome them but they are not easy to answer,” wrote Mrs. Kennedy in 1964.

Schoolchildren Make Visiting Scholar’s Duty Pure Pleasure

My most recent trip to the Monterey Peninsula as Visiting Scholar at the National Steinbeck Center was organized to further the Center’s connection to the increasingly diverse community of Monterey County and Salinas, California. Speaking at the Center about John Steinbeck’s career as a war correspondent in the context of the exhibit on Steinbeck at war was a real treat, as were my talks to John Wood’s high school English class in Salinas and the audience—mostly adult—attending a Saturday afternoon session at the Monterey Public Library. As a faculty member and administrator at Oklahoma’s largest public university, I make it a point to meet community groups whenever I can, and the individuals I encountered at each stop on my Monterey Peninsula itinerary came with interesting questions and intelligent insights about the author who helped make the region a literary legend. The library in Monterey is the oldest public library in California, and John Wood’s students are writing research papers on John Steinbeck, who attended high school in Salinas and college at Stanford. But the highlight of the trip was the time I spent with the youngest people on the schedule—fifth and sixth graders from area schools named for Cesar Chavez, John Steinbeck, and Dr. Oscar Loya, former superintendent of the Alisal school district east of Salinas. The kids’ energy was contagious, and their questions kept me on my toes most enjoyably. Their teachers and principals thanked me for coming, but on reflection the greater pleasure was mine. Helping to make John Steinbeck’s life and work relevant in children’s lives today can be a heady experience—one I recommend to those who, like me, research and write about John Steinbeck as faculty members at institutions of higher learning from Oklahoma to California.

John Steinbeck? Mais oui!

As a humorist I’ve learned that the best gags come from listening to people. Recently I broke one of my rules and picked up a couple hitchhiking on U.S. Highway 1, near Carmel, California. It turned out they were French and out to see the world, two things John Steinbeck liked most about life. When I asked them if they had read anything he wrote, the woman said oui! In France we read the raisins of anger! I liked her answer so much I put them up for the night and used the idea for “Life in the Grove,” the weekly cartoon I write for my home town newspaper, the Cedar Street Times.

Photo of Keith Larson at 2019 Steinbeck Festival by Elayne Azevedo

Dog Days Dampen Festival

One spring morning at Alice’s Dog Park in Pasadena, a few of us dog owners were talking about traveling with your dog when a gentleman in his 80s, named Larry, mentioned Travels with Charley in Search of America by John Steinbeck, a fellow dog-lover and former Californian. When I got home I ordered the book on Amazon and, a few days later, began reading. Several pages into the opening chapter of Steinbeck’s autumnal road trip story, I called to recommend it to my dog-obsessed mother back in Louisiana. At her local library she learned the state system appeared to have only one copy, which she would have to special-request. When I got to the section on school desegregation in New Orleans, near the end of Steinbeck’s narrative, I understood why.

I’d been assigned to read Of Mice and Men and The Red Pony in high school, and I was familiar with the classic films made from East of Eden and The Grapes of Wrath, so I knew John Steinbeck was an important writer who created robust settings and raw-hearted characters with whom, for whatever reason, I could easily identify. But I knew little about the causes of the author’s deeply held concern for the undervalued and marginalized, and the fraying of America’s moral fabric. Travels with Charley sparked my curiosity about this side of Steinbeck’s career.

An internet search for the whereabouts of Steinbeck’s custom 1960 GMC pickup truck, the Rocinante, led me to the National Steinbeck Center in his home town of Salinas, located five hours north of Pasadena. I was delighted to discover that the upcoming Steinbeck festival, the center’s annual event, would focus on Travels with Charley, and that attendees would have a once-in-a-lifetime chance to board the Rocinante. The theme of the 2019 festival was dogs, so I bought tickets and drove to Salinas on Saturday, August 3 with my mother, my wife, and three teenagers—our two sons and a neighbor’s—along for the ride.

Travel to Salinas in Search of John Steinbeck

We left early and arrived at 10:00 a.m. expecting crowds of Steinbeck fans, dog lovers, and social justice types, all eager to chat up strangers about Travels with Charley, like my friend Larry. Instead, a handful of early arrivals were milling about as staff members set up for the 10:30 tour of the Rocinante that had piqued my interest in the festival. While we waited I gave our neighbor’s son a rundown on John Steinbeck. The mention of The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, and East of Eden drew a blank stare. The clue about East of Eden—“You know, one of the three movies James Dean made before he died”—caused a response. “Who’s James Dean?”

The Rocinante tour, led by Tom Lorentzen (a.k.a. John Steinbeck), was educational and entertaining, and there was something for everyone on the schedule for the rest of the day: a dog show, a walking tour of downtown, a writers workshop, a scavenger hunt and games for kids, a road trip scene-painting booth, a staged reading of Travels with Charley, a food-and-beverage fundraiser, live music, and more. The highlight for me was author Peter Zheutlin’s talk about writing The Dog Went Over The Mountain—a Travels with Charley-inspired narrative comprised of events and encounters experienced by Zheutlin during his six-week cross-country journey, in a BMW convertible, with his dog Albie.

Unfortunately, none of the crowds for the day’s activities topped 50, and by my count there were no more than 150 people, total, in attendance on August 3, the first full day of the festival. A white poodle—the single entry for the dog show—won Best Charley Lookalike, Best Dressed, and Best Personality. Scheduled for an hour and a half, the canine contest was over in five minutes. The kids games had few players, or none, and the photo booth was quiet. The bookstore looked empty. The food and beer booths, set up to raise money, were also lonely.

I’d read about large crowds at past festivals when I was doing my research, so I wondered what could have caused the drop in this year’s attendance. Was the change in date from early May to the dog days of August at fault, or was it the ticket price of $50-$60 for a festival that used to be free? Could teachers be to blame for declining interest among teenagers (like our neighbor’s son), who never read Steinbeck because he wasn’t assigned? Disappointed by the trip, I headed back to home to Alice’s Dog Park—In Search of John Steinbeck.

Christopher Dickey Asks: Was John Steinbeck a CIA Informant in Paris in 1954?

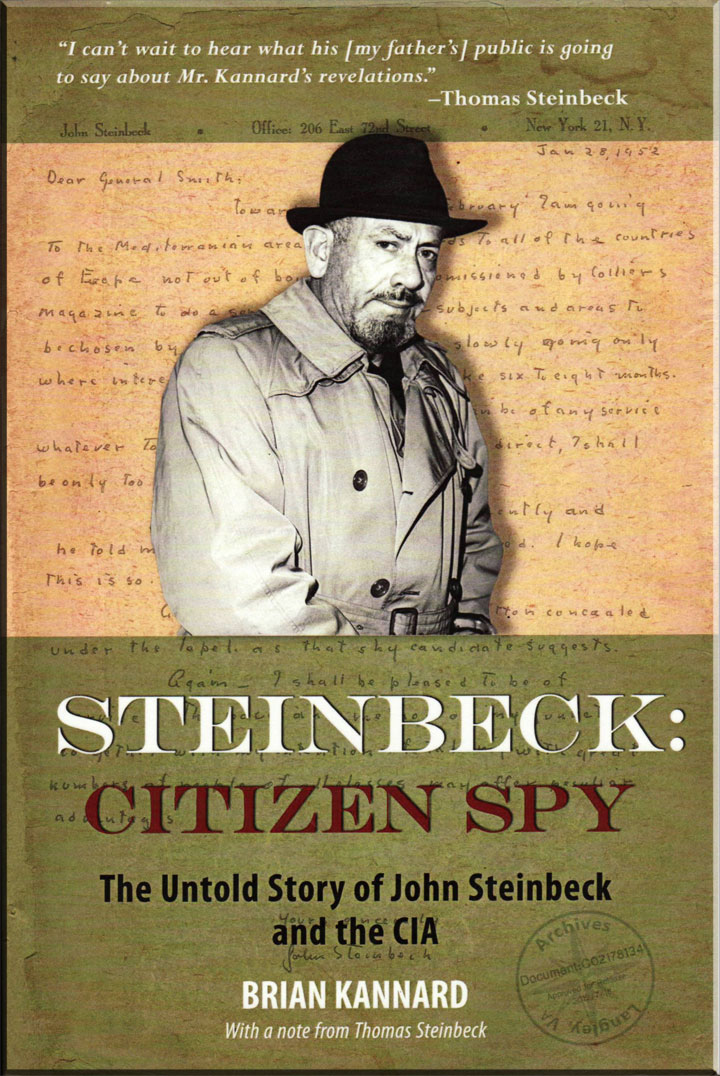

Was John Steinbeck acting as a CIA informant in Paris the summer he wrote the satirical short story for Le Figaro, published in English for the first time in the current issue of The Strand, about a haughty French chef and his hyper-finicky cat? That’s the question raised in a provocative Daily Beast piece by Christopher Dickey, the Daily Beast’s Paris-based world-news editor. Working his way to a firm maybe, Dickey quotes John Steinbeck’s contemporaneous correspondence with his New York agent, Elizabeth Otis, and Thom Steinbeck’s eye witness account—first cited by Brian Kannard in his 2013 book Steinbeck: Citizen Spy—of daily visits to the Steinbeck’s residence at 1 Avenue de Marigny by a man from the U.S. embassy with an attaché case. The son of a famous father, like Thom Steinbeck, Christopher Dickey is a frequent contributor to Foreign Affairs, Vanity Fair, The New York Times, MSNBC, CNN, France 24, BBC TV, and Al Jazeera.

New Light on John Steinbeck at Stanford’s Green Library

A trove of documents donated to Stanford University—the S.J. Neighbors collection of John Steinbeck papers, 1859-1999—adds dramatic detail to a literary life story that started in 19th century Germany and Palestine and became synonymous with 20th century California and America. Totaling 256 items, the acquisition is the largest since 1999, when Wells Fargo funded the addition of a major collection of Steinbeck material to the holdings of the newly renovated Green Library, which first opened in 1919, the year Steinbeck enrolled at Stanford as a freshman. The new collection includes correspondence to and from John Steinbeck, notebooks kept by his American grandmother, Almira Steinbeck, and lecture notes written by her earnest, German-born husband about their missionary work in Palestine and the attack on their compound in Jaffa that sent them packing for the United States, just in time for the outbreak of the Civil War. According to Rebecca Wingfield, curator of British and American literature, the addition of the S.J. Neighbors collection makes the Stanford University Library the most important resource anywhere for research on Steinbeck’s roots. Her colleague Ben Stone, curator of American and British history, notes that the school’s commitment to Steinbeck includes access to the collection by regular readers of the restless American writer who never got around to telling his grandparents’ back story and disappointed his family by leaving Stanford without a degree.

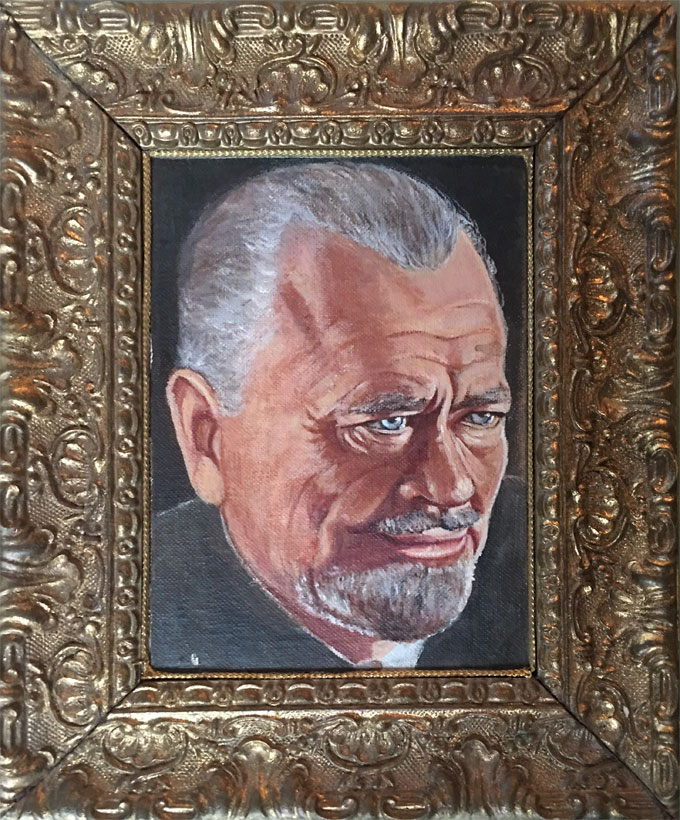

Painted 50 Years Ago, Lost Portrait Comes to Light

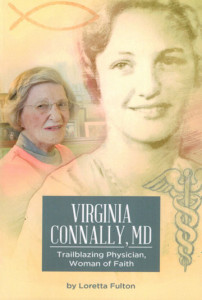

The lucky purchase by a young couple in Austin, Texas—of a lost portrait of John Steinbeck painted by an admirer 50 years ago—presents intriguing questions about the California author’s connection to Texas, the state he celebrated in Travels with Charley because, he said, his wife Elaine grew up there. Anthony Verdecanna, a specialist in mid-20th century furniture, and his wife Whitney, a musician, came across the elegantly framed find recently at an estate sale near Austin. The inscriptions on the back—“To Elaine Steinbeck” and “Virginia Boyd in Thailand 1969”—piqued their curiosity about its provenance. Following the trail of “Jenny Boyd,” the person who signed the work, they learned that the Virginia in the inscription was most likely the artist’s mother, Virginia Hawkins Boyd Connally, a pioneering physician in Abilene and the widow of Ed Connally, chairman of the Texas Democratic Party during the heyday of Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson. An eye-ear-nose-and-throat specialist whose first husband

The lucky purchase by a young couple in Austin, Texas—of a lost portrait of John Steinbeck painted by an admirer 50 years ago—presents intriguing questions about the California author’s connection to Texas, the state he celebrated in Travels with Charley because, he said, his wife Elaine grew up there. Anthony Verdecanna, a specialist in mid-20th century furniture, and his wife Whitney, a musician, came across the elegantly framed find recently at an estate sale near Austin. The inscriptions on the back—“To Elaine Steinbeck” and “Virginia Boyd in Thailand 1969”—piqued their curiosity about its provenance. Following the trail of “Jenny Boyd,” the person who signed the work, they learned that the Virginia in the inscription was most likely the artist’s mother, Virginia Hawkins Boyd Connally, a pioneering physician in Abilene and the widow of Ed Connally, chairman of the Texas Democratic Party during the heyday of Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson. An eye-ear-nose-and-throat specialist whose first husband  was named Fred Boyd, Dr. Connally was born in 1912 and died on March 31, 2019, leaving her daughter Genna Boyd Davis, an art education major in the 1960s, as her sole immediate survivor. Like a story by Steinbeck, the heroic narrative of Virginia Connally’s life presents multiple possibilities. Did she and Ed meet John and Elaine in Texas through the Johnsons, with whom the Steinbecks were friendly? Or was the writer’s generous portrait of Texas in the pages of Travels with Charley enough to win her affection—and the tribute of a devoted daughter’s painting, lost for 50 years until its discovery by yet another power couple from Elaine Steinbeck’s home state?

was named Fred Boyd, Dr. Connally was born in 1912 and died on March 31, 2019, leaving her daughter Genna Boyd Davis, an art education major in the 1960s, as her sole immediate survivor. Like a story by Steinbeck, the heroic narrative of Virginia Connally’s life presents multiple possibilities. Did she and Ed meet John and Elaine in Texas through the Johnsons, with whom the Steinbecks were friendly? Or was the writer’s generous portrait of Texas in the pages of Travels with Charley enough to win her affection—and the tribute of a devoted daughter’s painting, lost for 50 years until its discovery by yet another power couple from Elaine Steinbeck’s home state?