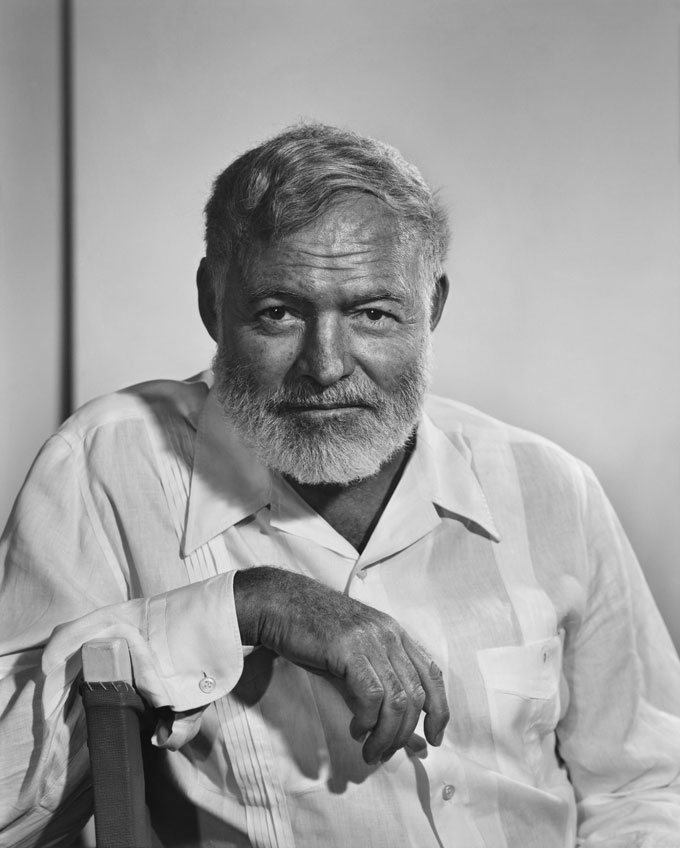

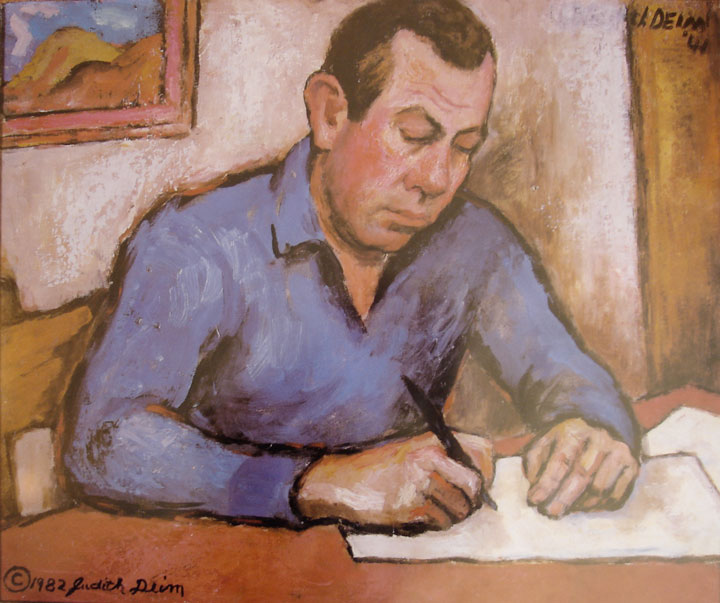

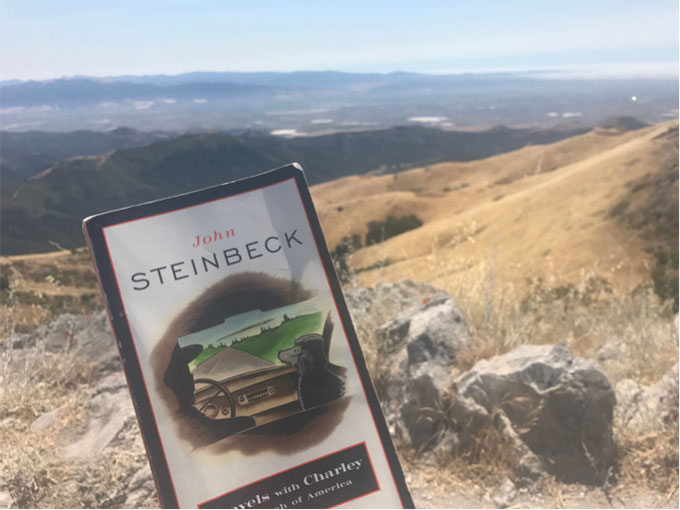

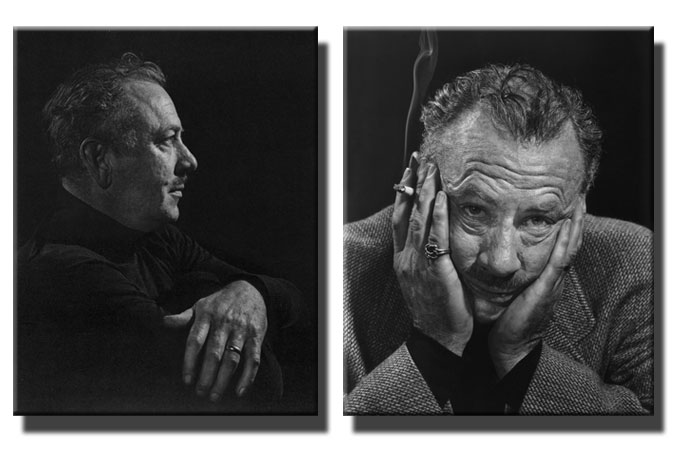

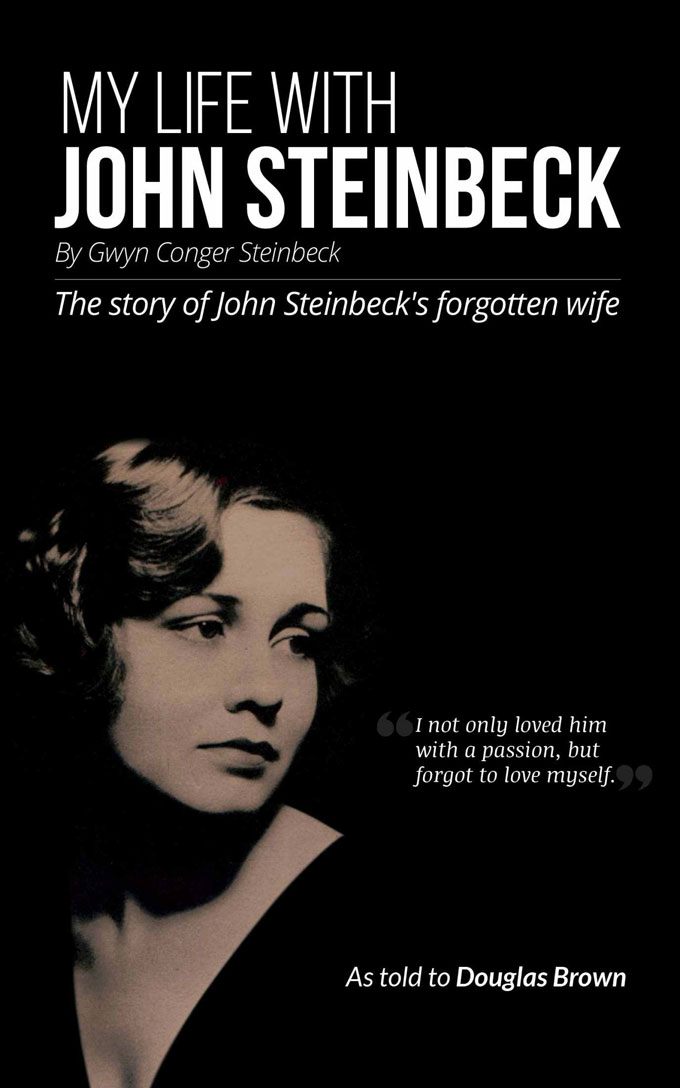

When Ernest Hemingway died, John Steinbeck suspected suicide and praised Hemingway’s writing, but knew Hemingway had disparaged his, viewing him as a literary competitor. Michael Katakis, the award-winning photographer and cultural critic who divides his time between Paris and Carmel, spoke recently about becoming Hemingway’s literary executor, editing Ernest Hemingway: Artifacts from a Life, and putting Hemingway and Steinbeck in comparative perspective as contrasting authors who remain popular with contemporary readers despite their differences. The recorded conversation took place on January 31, 2019 at the Carmel Public Library. Like the photography of Yousuf Karsh, the light it sheds on Ernest Hemingway also extends to John Steinbeck, whose life is the subject of a new biography by William Souder—scheduled for publication in 2020—that may comment further on the relationship of two figures with more in common than either ever acknowledged.—Ed.

An Evening’s Conversation: Ernest Hemingway and Traveling the World from Harrison Memorial Library on Vimeo.