Steve Hauk, the author of Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, contributed to this account of an overlooked aspect of John Steinbeck’s life, writing, and reputation as a 20th century American internationalist: his association with the Swedish writer Vilhelm Moberg, with whom he shared political sympathies, geographical proximity, and personal traits, including depression.—Ed.

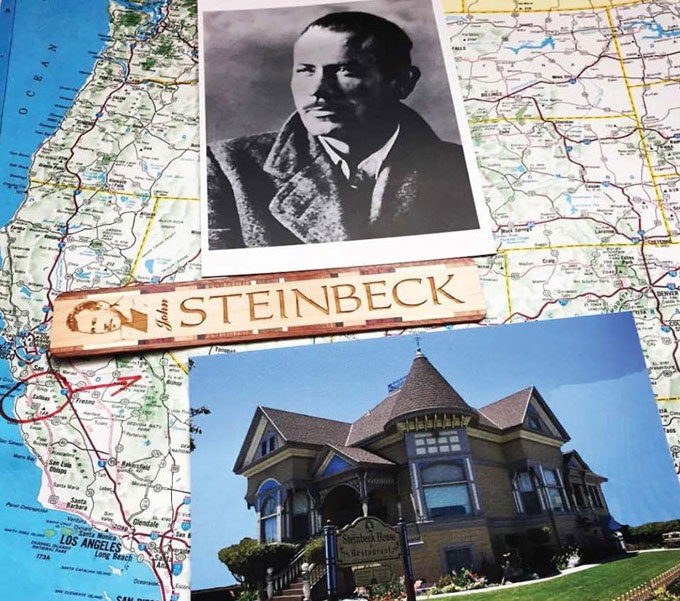

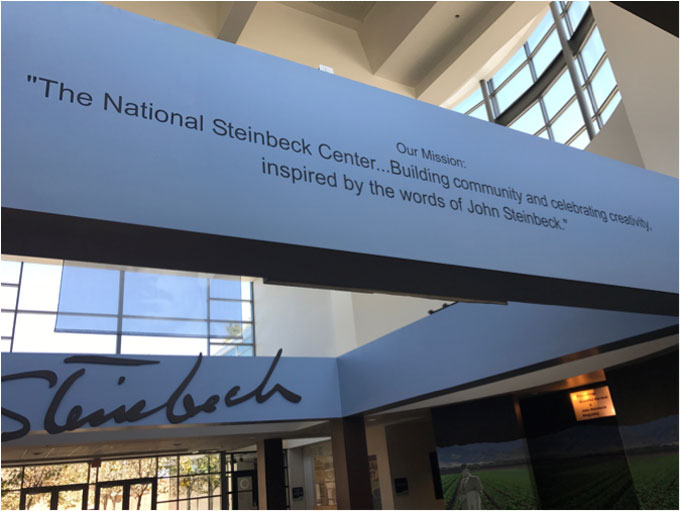

John Steinbeck and Vilhelm Moberg had more in common than literary greatness. Sensitive to the humble, powerless, and downtrodden, both writers documented social injustice with abiding sympathy and convincing clarity in works of fiction that became classics. Both wrote novelistic sagas of human migration that became major movies—Steinbeck’s 1930s protest novel The Grapes of Wrath and The Emigrants, the series of four novels in Swedish written by Moberg and made into a pair of feature films starring Liv Ullmann and Max von Sydow in the 1970s. Both men did some of their best writing on California’s Monterey Peninsula, though at different times, and may have met there in the late 1940s. “In one of his letters home, Moberg mentions having met Steinbeck,” notes Swedish scholar Jens Liljestrand, who speculates that the meeting must have been “brief and superficial,” given the barriers of language, age, and demeanor that separated them.

Both men did some of their best writing on California’s Monterey Peninsula, though at different times, and may have met there in the late 1940s.

Steinbeck died in 1968 at 66, and Moberg, who was born in 1898, committed suicide in 1973. But one thing is certain. If they were alive today both men would be deeply disturbed by the global refugee crisis and the resurgent nativism that has nurtured anti-immigration movements in Sweden, the United States, and across Europe. While Steinbeck focused on a family of Oklahoma tenant farmers driven west by natural catastrophe and Depression economics, Moberg followed a family of Swedish farmers who abandon the stony soil of Smaland in the 1800s for the promised land of rural Minnesota. Both took sides in parallel stories of epic struggle—for survival, dignity, and a place to call home. In each case, the dream of land and domicile motivated migration across states or seas by displaced souls, described most poignantly in the African American spiritual “Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child.”

Both took sides in parallel stories of epic struggle—for survival, dignity, and a place to call home.

When Vilhelm Moberg came to California in 1948, the Monterey Peninsula was about to face its own disaster—the depletion of the sardine population through over-fishing predicted by John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts, who died the year Moberg arrived. Gustaf Lannestock, a Swede who had worked as a masseur at the Hotel Del Monte and moved to Carmel, met Moberg walking on the beach and became his friend and translator. In 1998, the late Monterey County Herald columnist Bonnie Gartshore described the fateful encounter: “One day in 1948, Vilhelm Moberg, Sweden’s foremost novelist, took a rest from writing “Utvandrana” (“The Emigrants”). He had come to the Monterey Peninsula after long months of research to write the book, first of a [quartet] about Swedish families . . . in the 1800s. One way of relaxing after intense writing stints was to plunge into the surf at Carmel Beach.’’

Moberg came to the Monterey Peninsula to write a book about Swedish families in the 1800s.

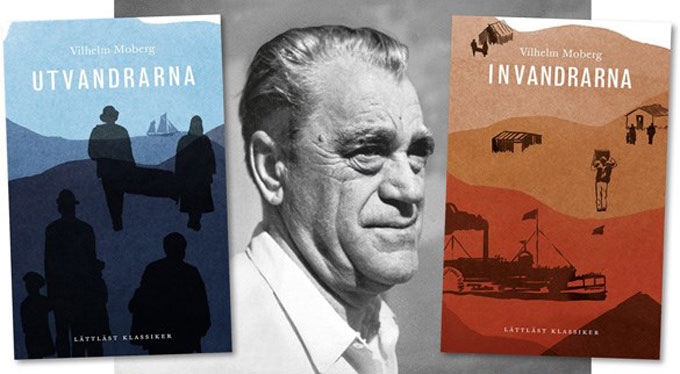

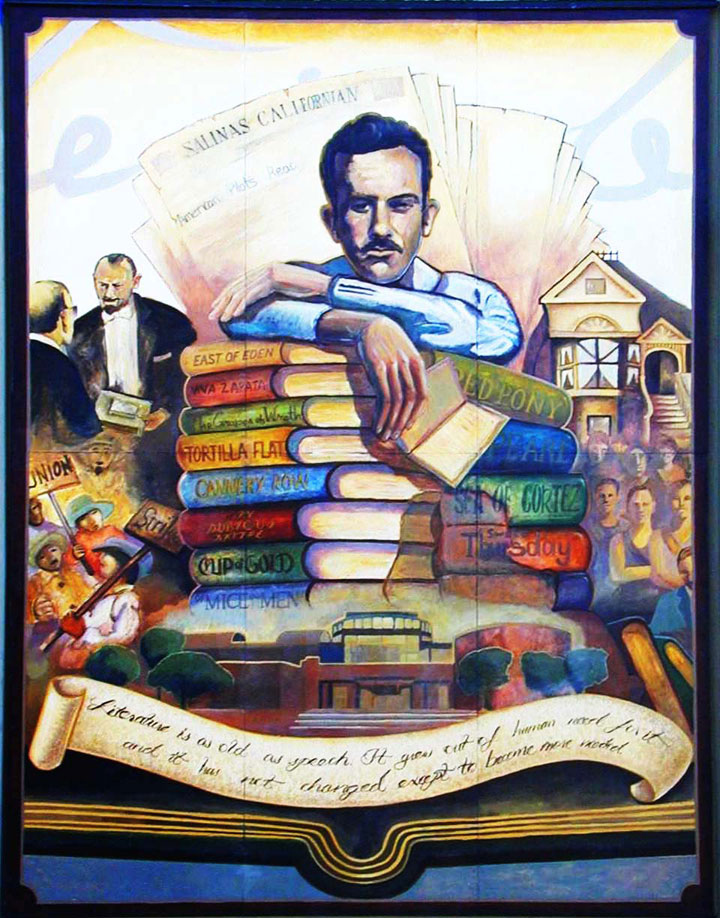

When Steinbeck lived in Pacific Grove in the 1930s he sought relief in the same fashion, exploring the tide pools with his friend Ricketts and gaining a sense of proportion. Lannestock and his wife Lucile enjoyed Swedish-style entertaining and their home attracted a party crowd, described by Liljestrand as the “cultural elite in Carmel,” that included Ricketts—who wrote of his friendship with Lannestock—and Steinbeck, as well as Robinson Jeffers. But according to Moberg, notes Liljestrand, the Lannestocks “didn’t socialize much with Steinbeck” because “they took his estranged wife’s side” when the Steinbecks moved to Los Gatos and their marriage collapsed. Steinbeck’s career eventually took him to Hollywood, Mexico, and Manhattan. He completed East of Eden, the California saga of his mother’s Irish-immigrant farm family, in New York. Moberg—who based his quartet of Swedish emigrant novels on the diaries of a Minnesota farmer—had finished the first two (shown here) in Carmel by 1952, the year East of Eden appeared.

When war came, neither Moberg nor Steinbeck was afraid to speak out. Moberg was openly critical of Sweden’s attempt at neutrality, and his 1941 novel Ride This Night, though set in the 17th century, is clearly a commentary on Nazi aggression. Steinbeck’s 1942 novella The Moon Is Down is about the invasion of an unnamed town in Scandinavia by an unnamed army that is unmistakably German. The book was outlawed in occupied Sweden, where Steinbeck had friends, but contraband copies were passed by hand and Steinbeck’s contribution to European morale was cited when he received the Nobel Prize from the Swedish Academy. The Steinbeck-Moberg connection can also be seen in Arvid and Robert, characters in The New Land who, as the film critic Terrence Rafferty observed, “have come to resemble Lennie and George, the wanderers of John Steinbeck’s ‘Of Mice and Men’” in the 1972 motion picture adaptation of the second novel in Moberg’s emigrant series. The movie’s director was Jan Troell, a Swede who shared Steinbeck and Moberg’s vision of the emigrant experience—and who came to the Monterey Peninsula in 1974 to shoot Zandy’s Bride, also starring Liv Ullman.

When war came, neither Moberg nor Steinbeck was afraid to speak out.

Swedes are supposed to be solitary types who wait for others to break the ice, a function frequently served by friends like Lannestock and Ricketts, Moberg’s likely entrée to Steinbeck’s world. “According to Lannestock’s memoir,” notes Liljestrand, “Moberg’s English wasn’t very good. He mostly hung out with just the Lannestocks, with whom he spoke Swedish.” If Bonnie Gartshore is correct, Moberg made his way despite that obstacle. In Monterey, she says, “he enjoyed talking to Sicilian Fishermen whom he met on Fisherman’s Wharf, and he wrote an article about them for a Stockholm newspaper.” Devastated by the death of Ricketts and a second failed marriage, Steinbeck returned to Pacific Grove in 1949 to recover. Given their habit of taking walks, a meeting with Moberg could have occurred by accident. Given their reticence, it might have needed help.

Lannestock and Ricketts were Moberg’s likely entrée to Steinbeck’s world.

Like Steinbeck, Moberg enjoys an enduring reputation in the homeland he both criticized and celebrated in his writing. His novels are required reading in Sweden, where he’s revered as a journalist, historian, and playwright with more than two dozen dramas to his credit. Also like Steinbeck, he experimented with literary forms. Steinbeck will always be associated with Okie migration and intercalary structure for The Grapes of Wrath. The author who called The Emigrants series his “documentary novels” became synonymous with Swedish immigration to the United States. Neither writer was satisfied by the celebrity. In a letter to Toby Street, Steinbeck talked about “a longing for extinction” caused by the conviction he “had no home, never did”—cruelly ironic from one who, like Moberg, wrote so memorably of people searching for a home.

Neither Steinbeck nor Moberg was satisfied by the celebrity they achieved.

Like Steinbeck, Moberg suffered from depression that grew worse with age. A radical democrat and political contrarian, he continued to speak out against monarchy, bureaucracy, and public corruption after he returned to Sweden. But he experienced writer’s block and his melancholy became despair. Early one morning in 1973 he left a letter of apology for his wife and drowned himself. “The time is twenty past seven; I go to search in the lake for eternal sleep. Forgive me, I could not endure,” he wrote her. He is frequently paired with his fellow Scandinavian O.E. Rolvaag, the author of Giants in the Earth. But he had much in common with his fellow Californian, John Steinbeck. The connection is overlooked, but it extended to war, depression, and epic protest against epic injustice. In light of current events, it’s worth remembering.