This week marks four years of weekly posts at SteinbeckNow.com celebrating John Steinbeck’s life and work, the relevance of his writing to current events, and new art inspired by his enduring fiction. Features posted in August 2013 included new music, visual art, and creative writing, along with a young painter’s reflection on Steinbeck’s artistic impact and a piece about Steinbeck’s home movies by a professional videographer. Other posts discussed Steinbeck’s writing habits, his scrutiny by the FBI, and the connection between the campaign of character assassination waged against Steinbeck in the 1930s and 1940s and the flight of Edward Snowden. Since launching as an independent, noncommercial site serving John Steinbeck’s international fandom, SteinbeckNow.com has published 365 posts that continue the pattern of originality and diversity set four years ago—previously unpublished critical and creative writing, new art and music, and thoughtful commentary from 60 contributors from as far away as North Africa. Along with critical and creative writing inspired by Steinbeck, news items and reviews are also welcome, provided they are original and do not duplicate existing online content. In keeping with its mission, SteinbeckNow.com does accept advertising or pay for material. If you’d like to be in the picture, email williamray@steinbecknow.com.

Help SteinbeckNow.com Celebrate Four Years of Celebrating John Steinbeck

The Salt Has Kept its Savor For the Reader Who Finds Religious Meaning in John Steinbeck’s Land and People

Although I have read and enjoyed most of John Steinbeck’s published writing, I am not a Steinbeck scholar and claim no special expertise. But I have lived in California’s Monterey County since 1950, and for many years I taught and coached in Salinas, the town where Steinbeck was born, went to school, and found religious meaning attending a local church. In a sense he never left, and my interpretation and appreciation of his work are colored by the land he lived on—the Salinas Valley and the Monterey Peninsula—and the people he wrote about: the poor and “the salt of the earth,” many of whom (to quote the Sermon on the Mount in the King James Version that Steinbeck read) had “lost their savour.”

In a sense Steinbeck never left Salinas or Monterey, and my interpretation and appreciation of his work are colored by the land he lived on and the people he wrote about.

Walking the hills and observing the vistas of Monterey County—from Fremont’s Peak in the Gabilans east of Salinas, to Mount Toro and the Corral de Tierra (the “pastures of heaven” where I now live), to Presidio Ridge in Monterey—these places have affected me deeply as I think they did John Steinbeck. Likewise, looking at the underground Salinas River from the East Garrison bluffs on the site of the former Fort Ord, where Steinbeck may have walked, suggests to me an undercurrent in the lives of the people who have lived on the surface of this land. Unavoidable, and taken for granted in Steinbeck’s time, were the sounds and smells and sights of Monterey Bay, of Cannery Row, of Fisherman’s Wharf, of lower Alvarado Street, of the Rodeo grounds in Salinas during Big Week, which he always enjoyed. Each one added to the grist and flavor of the characters and stories Steinbeck created or recreated in his fiction. I keep coming back to this all-encompassing environment when I read about his characters. These people were close to the earth.

I keep coming back to this all-encompassing environment when I read about his characters. These people were close to the earth.

As an impressionable boy in Salinas, Steinbeck observed poor Mexicans doing stoop labor in the fertile fields of the Long Valley near town, often alongside their children, who should have been in school. This experience prepared him to empathize with the legions of poor Americans looking for jobs in California in the 1930s—with the Dust Bowl farm families displaced by drought and economic depression who populate The Grapes of Wrath, with the unemployed single men moving from ranch to ranch and harvest to harvest in Of Mice and Men and In Dubious Battle.

In the End Melancholy Lifts, Like the Monterey County Fog

During my time teaching and coaching in the schools of Steinbeck’s home town, I interacted with the children and grandchildren of these people. I don’t see “Okies” anymore, but increasingly I do see down-and-out people standing on the corner in downtown Salinas with cardboard signs asking for work or money. The harsh realities faced by rural and small town Americans prior to World War II—the displaced Americans poignantly painted on Steinbeck’s word canvases—seem to have returned. Other vestiges of Steinbeck’s California can be found if one takes the time to walk, look, and listen to the land and the people on whose behalf Steinbeck’s books still bear witness: the emigrants and the immigrants, the homeless and the lonely, the powerless, and those whose lives lack spiritual or religious meaning.

Vestiges of Steinbeck’s California can be found if one takes the time to walk, look, and listen to the land and the people on whose behalf Steinbeck’s books still bear witness.

Read the books, then walk the land—the Monterey County of The Red Pony, Cannery Row, Tortilla Flat, The Pastures of Heaven, Of Mice and Men, East of Eden and The Long Valley; the sister valleys of The Wayward Bus, In Dubious Battle, and To a God Unknown. The living land evoked by Steinbeck largely remains. So does the emotional and thematic undercurrent that runs like a river through the lives of his characters. Many are spiritually, educationally, economically, or socially disadvantaged, unhinged, or bereft. Some find religious meaning. Most do not.

The living land evoked by Steinbeck largely remains. So does the emotional and thematic undercurrent that runs like a river through the lives of his characters.

My reading reveals a human dynamic in Steinbeck’s characters mirroring that of the land they inhabit, sometimes barely: drought followed by flood; summers of suffering followed by winters of discontent; deserts of isolation broken by moments of sustaining humanity that I would call Christian charity. Often melancholy rolls in like the morning fog. But the fog breaks eventually, and Steinbeck’s endings, though rarely happy, always seem hopeful to me.

Day’s End, oil on canvas by Warren Chang, 20” x 30” (2008), courtesy of the artist. ©Warren Chang.

Landscape with a Red Pony, oil on canvas by David Ligare, 32” x 48” (1999), courtesy of the artist. ©David Ligare.

The Gift Shop Visitor from England Who Wanted East of Eden to Go On Forever

Since moving to Salinas, California, I’ve volunteered twice monthly in the house where John Steinbeck grew up: one day assisting Chef Augie in the Steinbeck House restaurant kitchen and one working day in the Best Cellar, the book and gift shop in the basement that inspired the punny name. Because I work in the gift shop only once a month, it was a stroke of luck that I happened to be there on July 20, a busy day that began when my cohort John Mahoney and I saw reservations for 40 on the restaurant’s board upstairs. Forty was a good start. Counting walk-ins without reservations, it meant we could anticipate quite a few visitors to the gift shop before and after lunch. Even a slow day gets better when a “bluebird” visitor drops in and engages in fan chat about John Steinbeck. Along with near-record gift shop sales, July 20 also brought a bluebird encounter that I will never forget.

Even a slow day gets better when a ‘bluebird’ visitor drops in and engages in fan chat about John Steinbeck.

Shortly after we opened the door at 11 a.m., two parties came in: a father and teenage son from the Czech Republic and a 40-something couple from England with their small daughter. We’re used to foreign visitors in the gift shop, and the five we had that morning were talkative and friendly. Like his father, the teenager was clearly a Steinbeck fan—easy to tell as they zoomed past the shiny, pretty things and headed for the book section at the back of the shop. We stock some early editions of John Steinbeck, and the Czech father was visibly excited to find a vintage copy of The Red Pony to buy, lavishly illustrated, from the 1940s.

We’re used to foreign visitors in the gift shop, and the five we had that morning were talkative and friendly.

While the little English girl and her mum were occupied with the gift shop’s amazing dollhouse replica of Steinbeck House, one of our most popular not-for-sale items, John and I got to talking with the husband, who asked us what our favorite Steinbeck novel happened to be. We answered East of Eden, and he said he loved it, too. Then I mentioned that the first time I read the novel I dreaded getting to the end because I didn’t want the story to stop. The man’s response caught me by surprise: “Oh, my wife never did finish it for that reason.” I thought he was joking and turned to his wife. Yes, she said, ” I just didn’t want to know the end of those characters” after grieving over the death of Sam Hamilton, John Steinbeck’s grandfather, earlier in the story. Like me, she was familiar with the expression “book hangover,” which I confessed that I experienced when I finished reading East of Eden.

Like me, the woman from England was familiar with the expression “book hangover,” which I confessed that I experienced when I finished reading East of Eden.

Gift shop sales support the operation and maintenance of the house memorialized by John Steinbeck in East of Eden, and we were busy that morning. I would have welcomed more fan chat with the English couple, the Czech father, and the other bluebirds who visited during the day. Most of our out-of-town and foreign visitors on package tours of the Salinas-California area are focused on the rich history and Victorian architecture of the Steinbeck home. When lovers of Steinbeck’s fiction identify themselves, it’s a heartening reminder that our work helps to keep the house open and running. I’ve had other memorable experiences in the gift shop. But the standout will always be the English lady who couldn’t bring herself to finish East of Eden—not because it bored her, but because she loved the characters too much. I hope that some day she allows herself to read all the way to the end. Like the Steinbeck House, it’s graceful and glorious and gladdening.

Photo of Steinbeck House gift shop interaction by Angela Posada.

The Conversation with John Steinbeck’s Widow That Was All About Names, and Love

It was 1998. I had co-curated with Patricia Leach the inaugural art exhibition at the grand opening of the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California. A week or so after the opening I received a phone call from a woman with a Southwestern accent, or at least that’s what I judged it to be.

“Mr. Hauk, this is Elaine Steinbeck, the widow of the author John Steinbeck.”

“Hello, how do you do?”

“I am doing well, thank you. I was wondering if you would do me a favor, please.”

“Yes, of course.”

“Could you look in a Monterey County telephone book and tell me how many times you see my late husband’s name associated with a business or commercial enterprise?”

I opened my phone book to the businesses section and started flipping the pages to the S’s. I wondered how Mrs. Steinbeck picked me to call, then realized it must have been because she saw my name in conjunction with the exhibition at the National Steinbeck Center, This Side of Eden: Images from Steinbeck’s California.

Well, I found Steinbeck’s name tacked on to six or seven area enterprises. There was, I recall, a credit union, a used car dealership, and a dry cleaner, among other Steinbeck-somethings. As I read them off to Mrs. Steinbeck, she said, “Oh, my.” She said this or something similar several times in a charming sort of way. I joked that I might think of adopting the Steinbeck name for my business. She laughed, sort of. The commercialization of her husband’s name obviously bothered her, but she didn’t seem terribly upset, just mildly irritated and genuinely curious.

We talked for several minutes. She asked about the National Steinbeck Center and wondered how her husband was remembered in Monterey County. I found her a pleasant conversationalist. Over time, as I grew more interested in her late husband’s work, I regretted I didn’t ask for her phone number that day so I could call now and then to ask questions about his life.

The other day, I picked up the Monterey County phone book, turned to the business section, and flipped to the S’s. Some of the businesses with the Steinbeck name in 1998 had obviously closed, but new ones had sprouted up and the number using the author’s name was up eight, including a kennel (Steinbeck loved dogs), two realty firms (he owned houses in Monterey and Pacific Grove), a dental center (he said he met Ed Ricketts at the dentist’s), a café (think Bear Flag), a produce business (perfect fit), even an equine clinic for ponies, red and otherwise.

At her husband’s funeral in New York, Elaine Steinbeck asked his friends and mourners not to forget him. It isn’t what she had in mind at the time, but in a way that Steinbeck would probably appreciate, the continued commercial use of his name in Monterey County, 50 years after his death, is a sign of recognition and respect. I think she realized that and it’s the reason she called me 20 years ago. I’m glad I got to speak with her. She was smart and personable, like most Texans I know, and she was a theater person with an ear for poetry. When she died in 2003, her ashes joined John’s at the Salinas, California cemetery where, as she predicted (quoting Keats), she came to rest, like Ruth, “amid the alien corn” of her loved one’s people.

The voice I hear this passing night was heard

In ancient days by emperor and clown:

Perhaps the selfsame song that found a path

Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home,

She stood in tears amid the alien corn . . . .

(from “Ode to a Nightingale”)

Sharing East of Eden for the Jewish Festival of Shavout

The Jewish festival of Shavuot commemorates the Jewish people’s receipt of the Hebrew Bible and the ethical laws Torah contains. Though John Steinbeck wasn’t Jewish, the ethics of good and evil behavior, both within and outside ethical laws, are prominent in his writing beginning with The Grapes of Wrath, and the theme of Timshel—one’s response to evil—is a dominant feature of his partially autobiographical novel East of Eden. With that in mind, I recently took the opportunity to present a talk on Steinbeck’s treatment of Timshel in East of Eden to my local Jewish community as part of a program of Shavuot lectures in the Los Angeles area.

In my remarks I quoted passages from East of Eden (e.g., “the Hebrew word, the word Timshel—‘Thou mayest’— . . . gives a choice. It might be the most important word in the world. That says the way is open. That throws it right back on a man. For if ‘Thou mayest’—it is also true that ‘Thou mayest not’”) to explain Steinbeck’s fascination with the word Timshel in dramatizing the ethical choice we are given: whether to resist or succumb to the evil influences in our lives. I reviewed recent psychological research on how nature and nurture dictate our behaviors, as well as the Jewish teaching that emphasizes the responsibility of personal choice over good or evil, irrespective of nature, nurture, and perhaps even Divine influence. I also reflected on the intriguing typographical and transliteration mistake Steinbeck made in adapting the Hebrew word timshol to Timshel in East of Eden, along with Steinbeck’s influence on contemporary culture following this error.

My talk marked the conclusion to a remarkable personal East of Eden journey that brought with it a number of gratifying connections. As I noted in a previous post—“Discovering Unexpected Connections to East of Eden“—my adventure began with a visit to the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, where I examined a replica of the hand-carved box Steinbeck made to convey the manuscript of East of Eden that he gave to his beloved editor and publisher, Pascal Covici. The ensuing research I carried out into apparent errors in the Hebrew carved on the box prompted enjoyable discourse with archivists, academics, rabbinical scholars, and other experts around the world. It led to a report on my findings in a paper published in the winter 2015 issue of Steinbeck Review, and to my presentation during the Jewish festival of Shavuot.

All in all, a fascinating series of experiences, as a consequence of a family vacation visit to the National Steinbeck Center that was, in turn, inspired by my reading of The Grapes of Wrath when I was growing up in the United Kingdom.

University of Oklahoma Names David Wrobel Dean

David Wrobel, professor of American history at the University of Oklahoma, has been named interim dean of the school’s College of Arts and Sciences by David Boren, OU’s president. A specialist in the history of the American west and chair of OU’s history department, Wrobel is the author of Global West, American Frontier: Travel, Empire and Exceptionalism from Manifest Destiny to the Great Depression; Promised Lands: Promotion, Memory and the Creation of the American West; and The End of American Exceptionalism: Frontier Anxiety from the Old West to the New Deal. He teaches an interdisciplinary course in the College of Arts and Sciences on Steinbeck, the focus of his cognate-field work at Ohio University, where he studied Steinbeck with Robert DeMott and the late Warren French as part of his PhD curriculum in American intellectual history.

On the Road with Family in John Steinbeck’s California

David Wrobel received preliminary news concerning his appointment in early June while driving from the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California, to Pacific Grove, where he and his wife, Janet Ward (shown here), were vacationing with their daughter and sons at the Eardley Avenue cottage in which Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts began writing Sea of Cortez. His current book projects include America’s West: A History, 1890-1950, scheduled for publication in January 2018; We Hold These Truths: American Ideas and Ideals, from the Pre-Colonial Era to the Present; and John Steinbeck’s America, 1930-1968: A Cultural History. A native of London, England, he earned his undergraduate degree in history and philosophy at the University of Kent. Janet Ward, an interdisciplinary scholar of urban studies, visual culture, and European cultural history, is a professor history at the University of Oklahoma, where she directs the school’s Humanities Forum.

David Wrobel received preliminary news concerning his appointment in early June while driving from the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California, to Pacific Grove, where he and his wife, Janet Ward (shown here), were vacationing with their daughter and sons at the Eardley Avenue cottage in which Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts began writing Sea of Cortez. His current book projects include America’s West: A History, 1890-1950, scheduled for publication in January 2018; We Hold These Truths: American Ideas and Ideals, from the Pre-Colonial Era to the Present; and John Steinbeck’s America, 1930-1968: A Cultural History. A native of London, England, he earned his undergraduate degree in history and philosophy at the University of Kent. Janet Ward, an interdisciplinary scholar of urban studies, visual culture, and European cultural history, is a professor history at the University of Oklahoma, where she directs the school’s Humanities Forum.

John Steinbeck Surprises Visitors in Northern Ireland

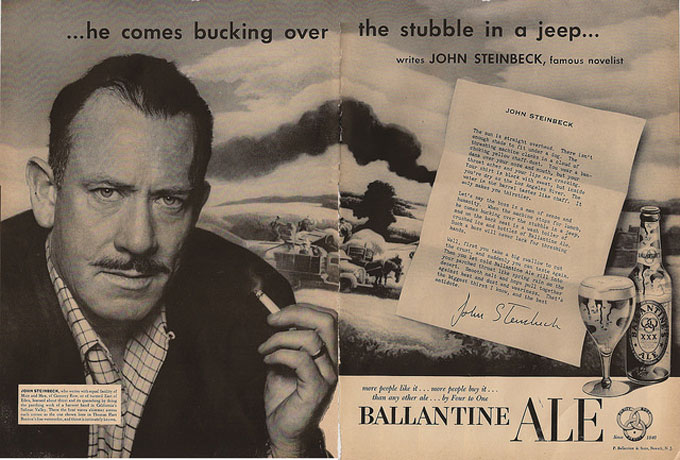

While traveling through Northern Ireland recently with her husband Tom O’Connell and sons Wyatt and Henry, Anne Hauk discovered this mural of John Steinbeck peering down from a building in the coastal town of Bushmill’s, three miles from Giant’s Causeway, the family’s destination. Steinbeck’s Ulster forebears emigrated to the U.S. during the 19th century famine that decimated the local population; 100 years later their celebrated grandson could be seen peering up from a glossy American ad promoting Ballantine’s Ale. Steinbeck, a sometimes self-effacing writer with an instinct for gadgets and whiskey brands, would be less surprised but also less gratified than Anne Hauk was by the apparition at Bushmill’s, home of Ireland’s legendary Black Bush label.

While traveling through Northern Ireland recently with her husband Tom O’Connell and sons Wyatt and Henry, Anne Hauk discovered this mural of John Steinbeck peering down from a building in the coastal town of Bushmill’s, three miles from Giant’s Causeway, the family’s destination. Steinbeck’s Ulster forebears emigrated to the U.S. during the 19th century famine that decimated the local population; 100 years later their celebrated grandson could be seen peering up from a glossy American ad promoting Ballantine’s Ale. Steinbeck, a sometimes self-effacing writer with an instinct for gadgets and whiskey brands, would be less surprised but also less gratified than Anne Hauk was by the apparition at Bushmill’s, home of Ireland’s legendary Black Bush label.

A resident of San Francisco, Anne is the daughter of Steve Hauk, an art expert and playwright from Pacific Grove who has written a series of short stories about Steinbeck, Salinas, Monterey, and the bibulous culture of bygone Cannery Row. A Jack Daniels-John Steinbeck fan, Steve identified the source of the image in Bushmill’s as a photo of Steinbeck by Sonya Noskowiak, a member of the San Francisco photography collective f/64. In East of Eden, the autobiographical novel Steinbeck was writing when the Ballantine ad appeared, Steinbeck’s Grandmother Hamilton, a hard-shelled teetotaler, makes her husband’s life miserable with religion. But Sam Hamilton had the last word. A sympathetic character given to imbibing with friends when she wasn’t looking, he is the subject of a 2016 BBC television program on Northern Ireland’s contribution to the culture of the United States. That Steinbeck would toast.

Family travel photos courtesy Tom O’Connell.

Curing Verbal Tic Disorder On MSNBC’s Evening News

Last week I channeled my inner English teacher by urging greater attention to grammar in blog posts about John Steinbeck. As with Steinbeck, however, I had issues with my high school English teacher. Like Mrs. Capp, the Salinas High teacher who underestimated Steinbeck’s need for praise, a teacher named Margaret Garrett used negative attention against adolescent error at Page High School in Greensboro, N.C. Once a month in our senior English class each of us had to give a short speech without notes, facing the class and Mrs. Garrett’s gorgon gaze. Filler words—I mean, like . . . umm, you know—were sharply received. Uh . . . kind of, sort of, in any event—mumbling, cliché, butchered syntax produced a steep frown, and the noisy clap! clap! of Mrs. Garrett’s hard, red hands. The technique she used to cure teenage verbal tic-disorder was practiced and perfected and frightening. In my case it was effective, engendering a hypersensitivity to sloppy speech that makes the talking heads on MSNBC, my preferred purveyor of cable news, increasingly hard to watch and hear.

Compare the slow legato of John Steinbeck’s archived radio voice with the rapid staccato of Chris Matthews, Rachel Maddow, and Chris Hayes, who may be the most extreme example of stop-start arrhythmia on mainstream cable news. Close your eyes and count the filler words, clichés, and redundancies uttered by hosts and guests in an average on-air minute: I mean, you know, sort of, kind of, like . . . um, take a listen, tweet out, frame out, report out, break down, knock down, at the end of the day, now look . . . . Try to diagram the sentence that begins with this typical guest response: “Yeah, Chris, you’re absolutely right, yeah, but look [or take a listen to] . . . .” Imagine what John Steinbeck—a political sophisticate who thought bad syntax disqualified Dwight Eisenhower—would make of Donald Trump as president today, or of the contagious verbal tic disorder that has become the broadcast norm, corrupting discourse and advancing group-think. It’s the oral analog of thoughtless writing, caused by three attitudes Steinbeck abhorred: haste, inattention, and lazy following.

Compare the slow legato of John Steinbeck’s archived radio voice with the rapid staccato of Chris Matthews, Rachel Maddow, and Chris Hayes, who may be the most extreme example of stop-start arrhythmia on mainstream cable news. Close your eyes and count the filler words, clichés, and redundancies uttered by hosts and guests in an average on-air minute: I mean, you know, sort of, kind of, like . . . um, take a listen, tweet out, frame out, report out, break down, knock down, at the end of the day, now look . . . . Try to diagram the sentence that begins with this typical guest response: “Yeah, Chris, you’re absolutely right, yeah, but look [or take a listen to] . . . .” Imagine what John Steinbeck—a political sophisticate who thought bad syntax disqualified Dwight Eisenhower—would make of Donald Trump as president today, or of the contagious verbal tic disorder that has become the broadcast norm, corrupting discourse and advancing group-think. It’s the oral analog of thoughtless writing, caused by three attitudes Steinbeck abhorred: haste, inattention, and lazy following.

Exceptions stand out because they’re both rare and promising at MSNBC. My favorite example is a young Washington Post opinion writer named Catherine Rampell, a frequent guest on Hardball with Chris Matthews and The Last Word, Lawrence O’Donnell’s marginally more listenable show in the slot behind Matthews, Hayes, and Maddow. As a communicator Catherine is like John Steinbeck: she speaks as she writes, clearly and carefully. I’m thrilled with her because she tickles my testy inner English teacher—and because I first met her when she was a high-achieving high school student in Palm Beach, Florida, where her father Richard Rampell, a culturally-attuned accountant, was my friend and fellow in the fight for local arts funding. In the past I’ve complained about Palm Beach, about the Trumpettes of Mar-a-Lago who worship Donald Trump and his dumbing down of everything. Now it’s a pleasure to praise the place for producing his opposite: a splendid writer and speaker with a career in journalism that John Steinbeck would admire and probably envy. Look for Catherine Rampell on MSNBC. And listen. You’ll be hearing about her.

Exceptions stand out because they’re both rare and promising at MSNBC. My favorite example is a young Washington Post opinion writer named Catherine Rampell, a frequent guest on Hardball with Chris Matthews and The Last Word, Lawrence O’Donnell’s marginally more listenable show in the slot behind Matthews, Hayes, and Maddow. As a communicator Catherine is like John Steinbeck: she speaks as she writes, clearly and carefully. I’m thrilled with her because she tickles my testy inner English teacher—and because I first met her when she was a high-achieving high school student in Palm Beach, Florida, where her father Richard Rampell, a culturally-attuned accountant, was my friend and fellow in the fight for local arts funding. In the past I’ve complained about Palm Beach, about the Trumpettes of Mar-a-Lago who worship Donald Trump and his dumbing down of everything. Now it’s a pleasure to praise the place for producing his opposite: a splendid writer and speaker with a career in journalism that John Steinbeck would admire and probably envy. Look for Catherine Rampell on MSNBC. And listen. You’ll be hearing about her.

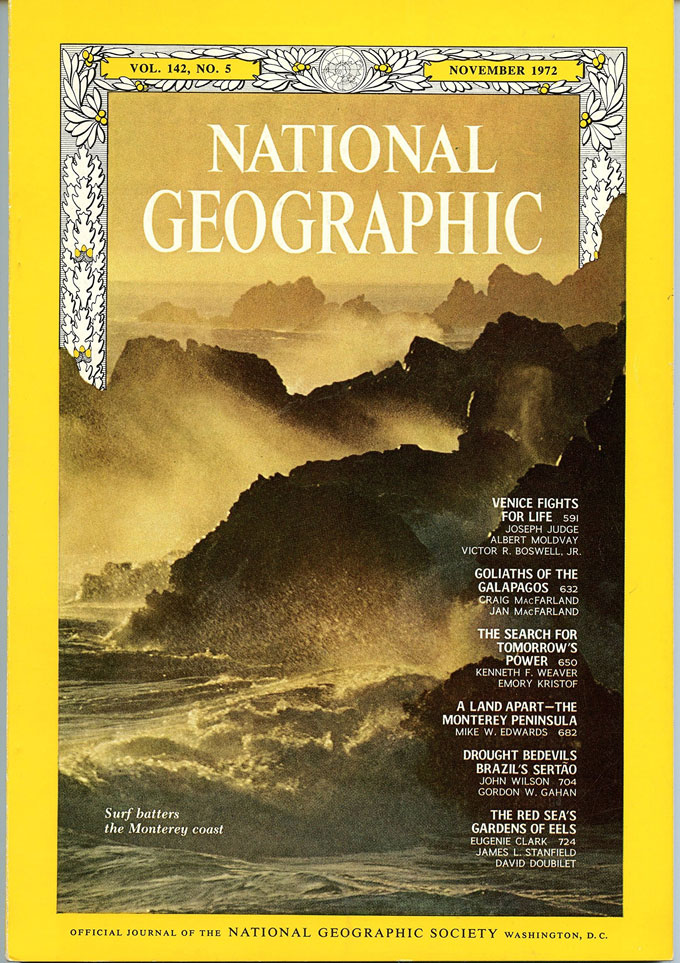

The Monterey Peninsula and John Steinbeck’s Myna Bird

Although I think he eventually changed his mind, in 1972 I was able to empathize with John Steinbeck’s dislike of being interviewed when a writer from National Geographic magazine came to California’s Monterey Peninsula to do a cover piece on the region. His name was Mike Edwards, and he phoned me to set up an interview. I had been a reporter for the Monterey Peninsula Herald, as it was called then, and had left there and was now working over the hill for the Carmel Pine Cone. Interviewing people was the same for both newspapers and I felt at ease with it. Being on the other side of the desk, being interviewed myself instead of doing the interviewing, seemed a natural, so I said yes when Mike called.

National Geographic Captured “Interesting Times” in 1972

These were interesting times in our region. The hippie movement was in full flux and kids were getting in trouble smoking weed and running away from Cleveland or Denver and hiding out from frantic parents on the Monterey Peninsula or down in Big Sur. I did a story for the Herald about a local mayor riding with the police to root out the hippies. The next day I encountered the mayor and, his eyes big, he said, “My God, that story you did on me—people are furious with me!’’ That reflects the way Monterey Peninsula people could be in those days. There was a lot of conservative money, yes, but most of the citizens believed in individual rights. They didn’t want a mayor to be a cop hassling hippies. When an oil company threatened to drill in Monterey Bay, protestors included hippies and others from the left, along with marchers from the right, joining in common cause. The oil company backed off.

These were interesting times in our region. The hippie movement was in full flux and kids were getting in trouble smoking weed and running away from Cleveland or Denver and hiding out from frantic parents on the Monterey Peninsula or down in Big Sur. I did a story for the Herald about a local mayor riding with the police to root out the hippies. The next day I encountered the mayor and, his eyes big, he said, “My God, that story you did on me—people are furious with me!’’ That reflects the way Monterey Peninsula people could be in those days. There was a lot of conservative money, yes, but most of the citizens believed in individual rights. They didn’t want a mayor to be a cop hassling hippies. When an oil company threatened to drill in Monterey Bay, protestors included hippies and others from the left, along with marchers from the right, joining in common cause. The oil company backed off.

When I met with Mike Edwards at my desk at the Pine Cone I was surprised to discover that, while interviewing others was easy, being interviewed made me uncomfortable. Though Mike was a gentleman, polite and professional, I was a nervous wreck. I was used to asking the questions, not answering them, and I was relieved when the November National Geographic appeared and I saw that Mike had been merciful. I was neither quoted nor mentioned in “A Land Apart – The Monterey Peninsula,’’ though I hoped I’d at least provided him with some decent background for his story.

Mike had come to the Monterey Peninsula deeply interested in the region through reading John Steinbeck. He wrote in his piece that he was drawn to the “derelict sheds – part corrugated metal, part masonry, part rusting clutter – that stand along the seven blocks of Cannery Row’’ by reading Cannery Row. Steinbeck’s friends Bruce and Jean Ariss helped him understand the area even more. The Arisses were on their way to becoming local legendary figures themselves, in part because of their friendship with Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts, but also because they were talented artists of great strength and character. Bruce was a painter and writer. Jean was the author of two novels—The Quick Years and The Shattered Glass.

“Being Quotable” About the Title of The Grapes of Wrath

“I spent an interesting afternoon in the company of Jean,” Mike wrote, “and her husband, Bruce, a writer, editor, and artist well known for his murals,” explaining that “they saw Steinbeck often in Edward Ricketts’ laboratory on the Row.‘’ After describing Steinbeck as “a large, thickset man, usually wearing jeans and a shabby sheepskin coat,” Jean told Mike about spending a day in 1939 with John Steinbeck, his wife Carol, and Ed Ricketts, going over the manuscript of John’s new novel, not yet titled. “She remembers Ricketts saying to Steinbeck, ‘This is a fine book – your best. It will win you the Nobel Prize.’ . . . The group spent the afternoon trying to think of a title, finally agreeing on ‘The Grapes of Wrath.’ “

“I spent an interesting afternoon in the company of Jean,” Mike wrote, “and her husband, Bruce, a writer, editor, and artist well known for his murals,” explaining that “they saw Steinbeck often in Edward Ricketts’ laboratory on the Row.‘’ After describing Steinbeck as “a large, thickset man, usually wearing jeans and a shabby sheepskin coat,” Jean told Mike about spending a day in 1939 with John Steinbeck, his wife Carol, and Ed Ricketts, going over the manuscript of John’s new novel, not yet titled. “She remembers Ricketts saying to Steinbeck, ‘This is a fine book – your best. It will win you the Nobel Prize.’ . . . The group spent the afternoon trying to think of a title, finally agreeing on ‘The Grapes of Wrath.’ “

That’s what you call being quotable. John Steinbeck gave Carol credit for the title, so perhaps it was on the day Jean recalled in her interview with Mike Edwards. I wish Jean had been more specific. If she were, I’m sure Mike would have reported it. He went on to a distinguished career, writing 54 articles from around the world for National Geographic. He was honored by the Foreign Correspondents Association for his writing on the nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl—something Steinbeck would have admired, the courage to cover that story—and he retired as a senior editor at National Geographic in 2002. He died last year in Arlington, Virginia.

Why do I think John Steinbeck eventually changed his mind about being interviewed? Because of a collection of 26 articles, all quoting Steinbeck, titled Conversations with John Steinbeck, edited by Thomas Fensch and published by the University of Mississippi. At times Steinbeck comes across as taciturn and uncooperative. At others he really seems to be enjoying himself. My wife Nancy and I picked up a copy several years ago in a little shop on Lighthouse Avenue in New Monterey, which used to have a half-dozen bookstores specializing in collectible editions. At the time I was working on a play about Steinbeck, setting him in his New York apartment at night, the only other characters a ghost, a talking myna bird, and a whirring tape recorder.

Why do I think John Steinbeck eventually changed his mind about being interviewed? Because of a collection of 26 articles, all quoting Steinbeck, titled Conversations with John Steinbeck, edited by Thomas Fensch and published by the University of Mississippi. At times Steinbeck comes across as taciturn and uncooperative. At others he really seems to be enjoying himself. My wife Nancy and I picked up a copy several years ago in a little shop on Lighthouse Avenue in New Monterey, which used to have a half-dozen bookstores specializing in collectible editions. At the time I was working on a play about Steinbeck, setting him in his New York apartment at night, the only other characters a ghost, a talking myna bird, and a whirring tape recorder.

I got the idea for the myna bird from a Steinbeck letter I traded for some years ago, a handwritten missive to Fred Zinnemann, the director of High Noon, From Here to Eternity, and other fine films. In the letter Steinbeck is giving the myna bird to Zinneman, and describes the bird’s character and required care. The tape recorder in the play was, I think (one can never be quite sure about these things) my own invention, perhaps inspired by reading that Steinbeck liked tinkering and “gadgets.”

The Imaginary Myna Bird With the Meaningful Name

Nancy and I took Conversations with John Steinbeck home, sat down on the couch, and opened it. One of the first interviews we read was a 1952 piece by New York Times drama critic Lewis Nichols interviewing Steinbeck in the author’s Manhattan apartment. They seemed to get along well as Steinbeck discussed work on the book that would become East of Eden. Steinbeck proudly mentioned having a writing room, something that—echoing Virginia Woolf—he considered of paramount importance. “This,” Nichols wrote, “is the first room of his own he ever has had.’’ Then: “It is a very quiet room. For companionship, Mr. Steinbeck would like to get a myna bird. With a tape recorder he would teach this to ask questions, never answer, just ask.’’

When we read that, Nancy looked at me and we laughed. We felt we were channeling John Steinbeck, though to this day I still haven’t finished the play. Neither have I given up. Someday. And someday I’d like to elaborate on Steinbeck’s charming myna bird letter to Zinnemann. Steinbeck, incidentally, called the myna bird “John L.”

When we read that, Nancy looked at me and we laughed. We felt we were channeling John Steinbeck, though to this day I still haven’t finished the play. Neither have I given up. Someday. And someday I’d like to elaborate on Steinbeck’s charming myna bird letter to Zinnemann. Steinbeck, incidentally, called the myna bird “John L.”

For the fighter John L. Sullivan? Or the labor leader John L. Lewis? Either one would be meaningful.

John Steinbeck’s To a God Unknown: How to Be a Writer In the Age of Donald Trump

It’s easy to read John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, winner of the 1940 Pulitzer Prize, and as Stephen King describes in his best-selling book On Writing, to have “feelings of despair and good old-fashioned jealousy—[thoughts like] I’ll never be able to write anything that good, not if I live to be a thousand.”

Like King’s wise counsel about how to be a writer, John Steinbeck’s masterwork is a “spur” that “goad[s] the writer to work harder and aim higher.” During President Donald Trump’s regime of diminished-to-defunct arts funding, new writers—in addition to emerging musicians, painters, sculptors, photographers, and all creative people committed to contributing to civilization through art—can take inspiration from the inauspicious circumstances surrounding the publication of Steinbeck’s difficult second novel.

In the introduction to the Penguin Classic edition of To a God Unknown—originally published in 1933, four years after Steinbeck’s first novel, Cup Of Gold, and six years before The Grapes of Wrath—the poet-scholar Robert DeMott writes that “Steinbeck labored longer on [it] than on any other book.” As DeMott notes, it took Steinbeck many, many revisions, crises in confidence, and almost five years to complete his second novel. (The Pastures of Heaven, published in 1932, is a sequence of stories—not a traditional novel—about the bad luck a new family brings to a happy valley.)

Flush with cryptic and crystalline allusions to paganism, Christianity, and the Greek epics, To a God Unknown is at base a pioneering tale. It tells the story of Joseph Wayne and his family leaving Vermont to homestead initially fertile but increasingly—and eventually, climactically and cataclysmically—drought-ravaged farmland in California’s southern Salinas Valley. Putting aside California’s recent rainy spell, and considering President Trump’s already abysmal record on global warming and the environment, one might say the book portends critical warnings for America’s future. In a journal entry, Steinbeck wrote, “[t]he story is a parable . . . the story of a race, growth and death. Each figure is a population, and the stones, the trees, the muscled mountains are the world – but not the world apart from man – the world and man – the one indescribable unit man plus his environment.”

Critical reviews of To a God Unknown were as savage as the feral wilderness it depicts. Virginia Barney opined in The New York Times that the novel was “a curious hodgepodge of vague moods and irrelevant meanings.” A book critic from The Nation characterized it as “pitifully thin and shadowy.” As Robert DeMott notes in Steinbeck’s Typewriter: Essays on His Art, “not [even] enough copies [of the book] sold [for the publisher] to recoup the small advance” Steinbeck received.

What if John Steinbeck Had Stopped Writing in 1933?

And yet it is precisely through this example of Steinbeck’s early literary stumbles that I submit all brave new artists can find the courage, the resoluteness, and the abiding faith in the value of their art to persevere through rough spots, honing their craft through lean times as Steinbeck did—at risk to wallet, ego, and at times, to relationships.

Imagine the gaping, un-fillable hole in American literature if, after the unfavorable reviews of To a God Unknown and The Pastures of Heaven, Steinbeck had decided to up and quit. What if, disheartened and disconsolate by the failure of To a God Unknown—which foreshadows elements and devices brought to masterful fruition in The Grapes of Wrath—Steinbeck had packed up his pen, paper, and typewriter, period, end of story—and I hasten to add, end of all his stories?

In 2014 the novelist David Gordon described the business of writing in The New York Times as “a risky and humiliating endeavor.” Softened by self-deprecation, Gordon’s column firmly gut-kicks prospective authors with an honest peek at the lonely, ascetic, self-possessed lives that most writers by necessity lead. “Let’s face it [Gordon observed]: just writing something, anything and showing it to the world, is to risk ridicule and shame. What if it is bad? What if no one wants to read it, publish it? What if I can’t even finish the thing?” Both during and after the writing of To a God Unknown and the book’s blisteringly bad reception, Steinbeck could have succumbed to any of these common writer’s ailments, never to be heard from again.

But he didn’t. He kept on writing instead.

To paraphrase Don Chiasson’s recent New Yorker magazine review of the biography of the poet Robert Lowell by Kay Redfield Jamison, “Perhaps [he had no choice, because as Gordon observed] being a writer is a bit like having Tourette’s, a neurological disorder. Or what psychologists call ‘intrusive thoughts’: unwanted and disturbing ideas and images that suddenly attack us unbidden. A need to speak the unspeakable thing.” Adds Chiasson, “mood disorders occur with staggering frequency in creative people, and writers seem to suffer the most.”

Perhaps. But unquestionably To a God Unknown—written when Steinbeck was a published-but-still-struggling 30-year-old grinding away in obscurity and insecurity—provides evidence of a sturdy self-belief, the kind of grit I submit all successful or striving artists must possess. This tough and necessary tenacity is embodied in Steinbeck’s advice to his friend and fellow novelist, George Albee: “Fine artistic things seem always to be done in the face of difficulties, and the rocky soil, which seems to give the finest flower, is contempt. Don’t fool yourself, appreciation doesn’t make artists. It ruins them. A man’s best work is done when he is fighting to make himself heard, not when swooning audiences wait for his paragraphs.”