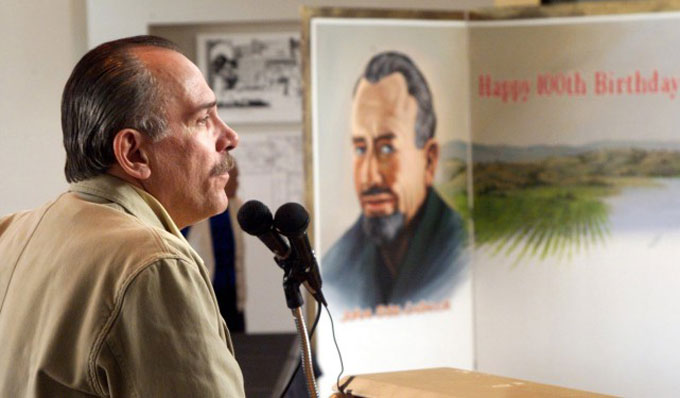

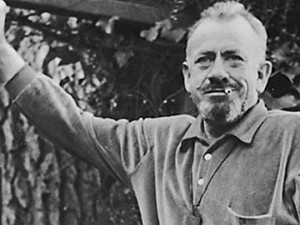

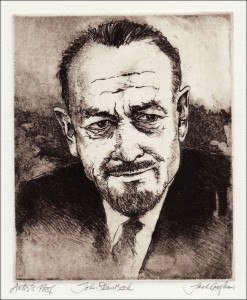

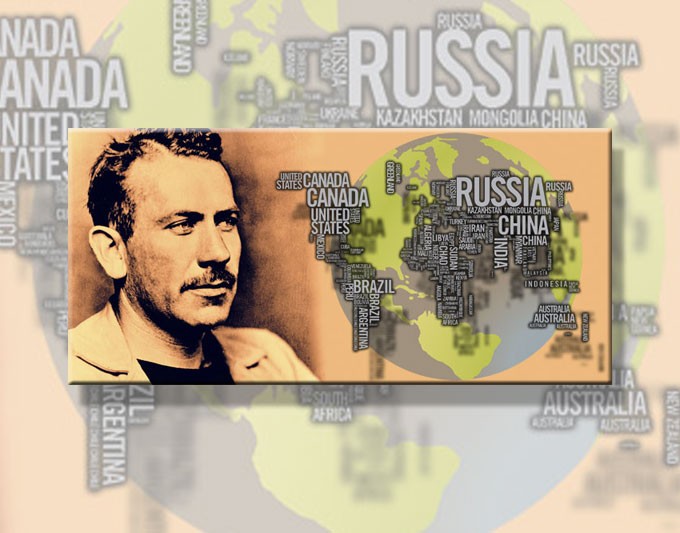

SteinbeckNow.com is the author website with an ambitious mission: to connect John Steinbeck, who preferred pencils, with readers accustomed to computers. Other American authors also have author websites. But most are designed for academics, or tied to venues or foundations raising funds for programs and projects. Steinbeck never wanted an academic title or degree; he even resisted when his home town attempted to name a school after him. Pitches for money made him uncomfortable and commercialism often made him angry. In this same spirit, the only non-academic author website that bears his name is non-commercial and focused on the present, not the past. Content comes from contributors who write for love, not money; new blog posts are published weekly, almost 300 since the site launched three years ago. Contributors, 48 to date, come from the United States, Europe, and Africa as well. Some write poetry, fiction, or drama inspired by Steinbeck’s life or work. A few are specialists who prefer to test their ideas online before writing their article or book. Most are amateurs who participate in Steinbeck’s books as he intended, with imagination. Thinking about John Steinbeck in a fresh or personal way? Put your thoughts in a blog post for the only Steinbeck author website created for readers like you. Content is curated and subject to editing, but turnaround is fast and layout looks appealing. Steinbeck thought imaginatively, then put pencil to paper. Now it’s your turn to write. Getting started is easy: email the idea for your blog post to williamray@steinbecknow.com.