Jane Fonda, the actress-activist daughter of John Steinbeck’s friend, the actor Henry Fonda, will receive the 2023 John Steinbeck “In the Souls of the People” Award on September 13 at San Francisco’s Herbst Theatre. The award is made annually by the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University. Previous awardees include Bruce Springsteen, Arthur Miller, and Joan Baez. In a January 27 post—“Even John Steinbeck Thought Henry Fonda Was The Perfect Pick For Grapes Of Wrath”—film writer Jeremy Smith celebrates the performance that helped make Henry Fonda famous, and John Steinbeck’s friend.

Henry Fonda’s Daughter, Jane Fonda, to Receive 2023 John Steinbeck Award

Washington Post: Read Steinbeck to Understand Russia and Ukraine

John Steinbeck’s wrote The Moon Is Down to inform Americans and inspire people in the formerly free countries of Europe—Norway, Denmark, Holland, France—occupied by Hitler’s forces in 1941. A March 1, 2022 op-ed in The Washington Post, by a literary-minded diplomat named Charles Edel, uses Steinbeck’s 1942 novella-play to educate another generation, and inspire resistance to another invasion and another dictator, eight decades later. “President Zelensky’s leadership of Ukraine’s resistance is a testament to democracy” profiles the Ukrainian president as a modern-day Mayor Orden, the fictional character Steinbeck likely modeled on the exiled mayor of Narvik, Norway. The op-ed’s subtitle—“How John Steinbeck’s ‘The Moon Is Down’ inspired resistance to occupation”—might give away the lede. But it will please fans of Steinbeck’s writing, which also includes A Russian Journal, Steinbeck’s 1948 nonfiction work in which Ukrainians emerge as victims of central planning and Russian belligerence. But that’s a subject for another op-ed on John Steinbeck’s continuing relevance.

Photo of Theodor Broch, the exiled mayor of Narvik, Norway.

The New Yorker Finds John Steinbeck Serious, Funny

The January 24, 2022 New Yorker magazine puts John Steinbeck in the friendliest possible light—twice in one issue—by exploiting his popularity as an enduring cultural meme for purposes both serious and silly. The pop-music department profile of John Mellenkamp, by Amanda Petrusich, opens with a sober account of the John Steinbeck “in the souls of the people” humanitarian award, which was conferred in 2012 on the Indiana-born singer-songwriter known, like the award’s namesake, for employing art to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. Elsewhere in the magazine, the weekly humor column by David Kamp satirizes such Steinbeckian over-seriousness by ascribing qualities to the “Established Creative” type of COVID-era dating partner that Steinbeck might have recognized in himself: “The hetero package comes with a Jaguar E-Type, attractively shelved first editions of John Steinbeck, and a meticulously catalogued collection of rare jazz ’78s.” Fair warning, however. “Extremely successful creative can be more susceptible to messiah complexes, infidelity, [and] using Jessica Chastain as a communications proxy.”

Photo collage: John Steinbeck flanked by serio-comic “Established Creative” co-types, Orson Welles (left) and Burgess Meredith. Not shown: Fred Allen, the comic writer and occasional New Yorker contributor who remained Steinbeck’s close friend until Allen’s death in 1956.

Film on Ernest Hemingway Fails to Mention Steinbeck

It was a slog at times, and Ernest Hemingway the man repeatedly came off as a really unlikable jerk, but I made it through Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s Hemingway fest on PBS. Boy, was Hemingway a strange, mean, and multi-troubled soul. By comparison, he makes John Steinbeck’s grumpy persona look saintly.

There are interesting parallels between Hemingway and Steinbeck, though, especially their struggles with booze/drugs, their need to prove their manhood in war, and their rocky marriages and fatherhood failings. They were also equally terrified of speaking in public or on TV. Hemingway’s fame and influence surpassed Steinbeck’s and every other writer before and after World War II. But it was odd that Novick and Burns never mentioned Steinbeck at all.

Scott Fitzgerald had a few cameos. The name John Dos Passos was dropped. But you would have thought Hemingway was the only important American novelist alive after 1938.

Hemingway’s Action “Unnecessarily Cruel and Stupid”

Burns could have slipped Steinbeck into the program—and provided a redundant example of what an ass Hemingway was—by mentioning the only meeting between the two literary heavyweights. As Jackson Benson describes it in his biography, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer, Hemingway expressed the wish to meet Steinbeck in the spring of 1944 when they were both in New York City.

It must have been quite an event. The dinner party at Tim Costello’s on Third Avenue took weeks to arrange, was attended by Robert Capa (at left in World War II photo with Army driver and Hemingway, right), John O’Hara, and John Hersey and—says Benson—turned out to be pretty much a disaster. The only memorable incident was when Hemingway and O’Hara were at the bar arguing over the authenticity of the old blackthorn walking stick Steinbeck had given O’Hara. As Benson tells the story, to prove that the walking stick—which had been handed down to Steinbeck by his grandfather—was not the real deal, Hemingway bet O’Hara 50 bucks he could break it over his head.

“O’Hara accepted,” Benson writes. “Hemingway took the stick by both ends and pulled it down over his head, breaking it in two. ‘You call that a blackthorn?’ he said, and threw the pieces aside. O’Hara was mortified, while Steinbeck . . . looked on and thought the whole thing was unnecessarily cruel and stupid.”

Benson says Steinbeck admired Hemingway more than any other writer of his time. But it was Hemingway’s writing skills Steinbeck admired, not his creepy he-man personality. Based on Burns and Novick’s six-hour biography, Steinbeck had it right.

Ken Burns received the 2013 John Steinbeck award for humanitarian achievement given by the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University. Michael Katakis—a consultant and major contributor to the Hemingway film—is an essayist, fiction writer, and photographer who divides his time between Paris, London, and Carmel, California. Bill Steigerwald recently released the e-book version of his book on Ray Sprigle, which includes the original 21-part series reporter Sprigle wrote about his undercover journalism mission in the Jim Crow South in 1948.—Ed.

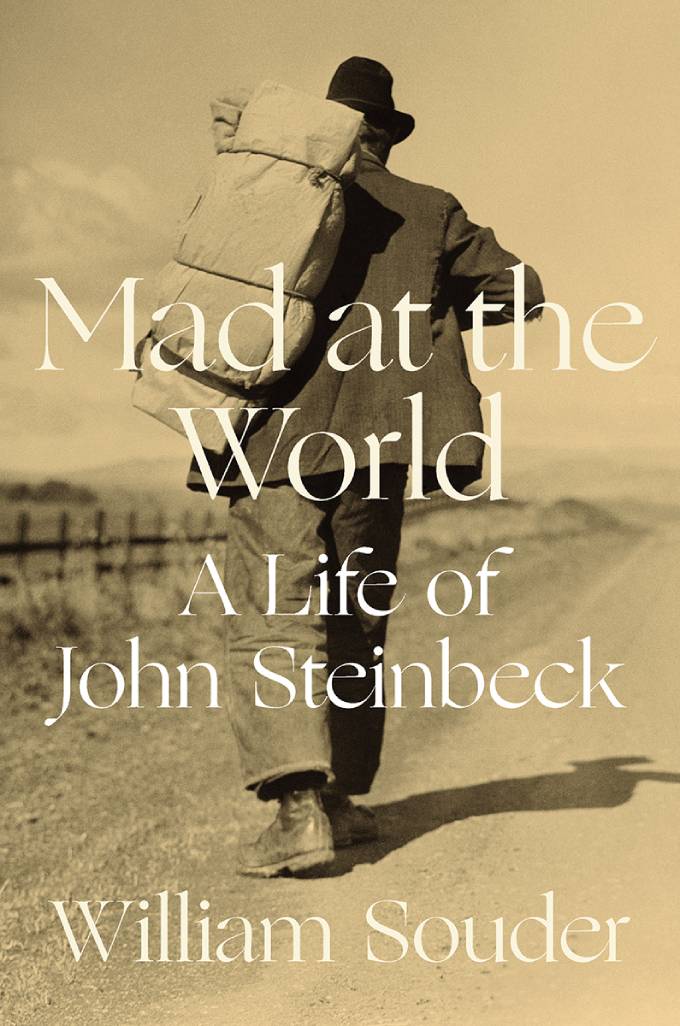

William Souder’s Life of John Steinbeck Wins Los Angeles Times Biography Book-Prize

William Souder’s Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck has won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in biography. The announcement was made at a virtual ceremony on April 16, 2021. Also nominated for the annual award were biographies of Sylvia Plath, Malcolm X, Andy Warhol, and Eleanor Roosevelt, John Steinbeck’s champion in the controversy surrounding the publication of The Grapes of Wrath 82 years ago. Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck received widespread praise when it was published by W.W. Norton & Co., starting with a September 14, 2020 pre-publication review by Donald Coers at SteinbeckNow.com.

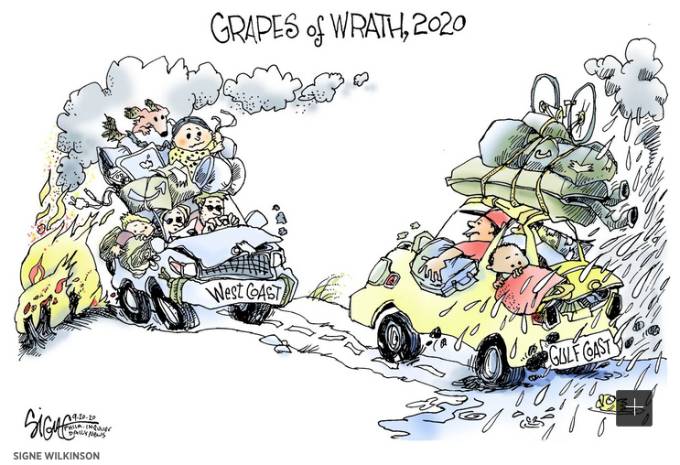

John Steinbeck Drives Humor in Political Cartoon

Writing about the prickly presidential election cycle of 1960, John Steinbeck was prepared to find the humor in politics and, when also writing about his favorite comic strip, “Li’l Abner,” the politics in humor as well. Steinbeck died a month after Richard Nixon’s election in 1968, but if he were still alive he would likely be laughing at this September 20, 2020 political cartoon by Signe Wilkinson. Showing two carloads of families in flight but coming from opposite directions—one from West Coast fire, the other from East Coast weather—it drives its point home with the caption “Grapes of Wrath, 2020.” A Pulitzer Prize-winning political cartoonist at the Philadelphia Inquirer, Wilkinson clearly enjoys irony à la Steinbeck. “This year, with smoke from the western fires reaching D.C., Congress should start addressing our own environmental problems,” she explained. “It’s in everyone’s best interests. Republicans certainly wouldn’t want fleeing Californians invading their states.”

Image courtesy Signe Wilkinson/Philadelphia Inquirer.

Flash! Catholic News Agency Is Up with The Moon Is Down

Year-end book lists may be boring, but one outlet’s pick for editor’s favorite in 2019 surprised fans familiar with John Steinbeck’s bumpy treatment by religiously-minded reviewers. Catholic News Agency, an affiliate of Eternal Word Television Network in Denver, Colorado, chose The Moon Is Down for reader attention in a December 31 round-up that includes a French priest’s commentary on the Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas, A Testimonial to Grace by American Cardinal Avery Dulles, and Three to Get Married by “not-so-soon-to-be-blessed Fulton Sheen,” the photogenic philosopher-bishop who hosted the popular TV show Life Is Worth Living in the 1950s. (CAN’s deputy editor-in-chief, Michelle La Rosa, paired Steinbeck’s 1942 novella-play with a 1990 novel, The Remains of the Day, by Nobel Laureate Kazuo Ishiguro.)

Photo courtesy Catholic Herald/Catholic News Agency.

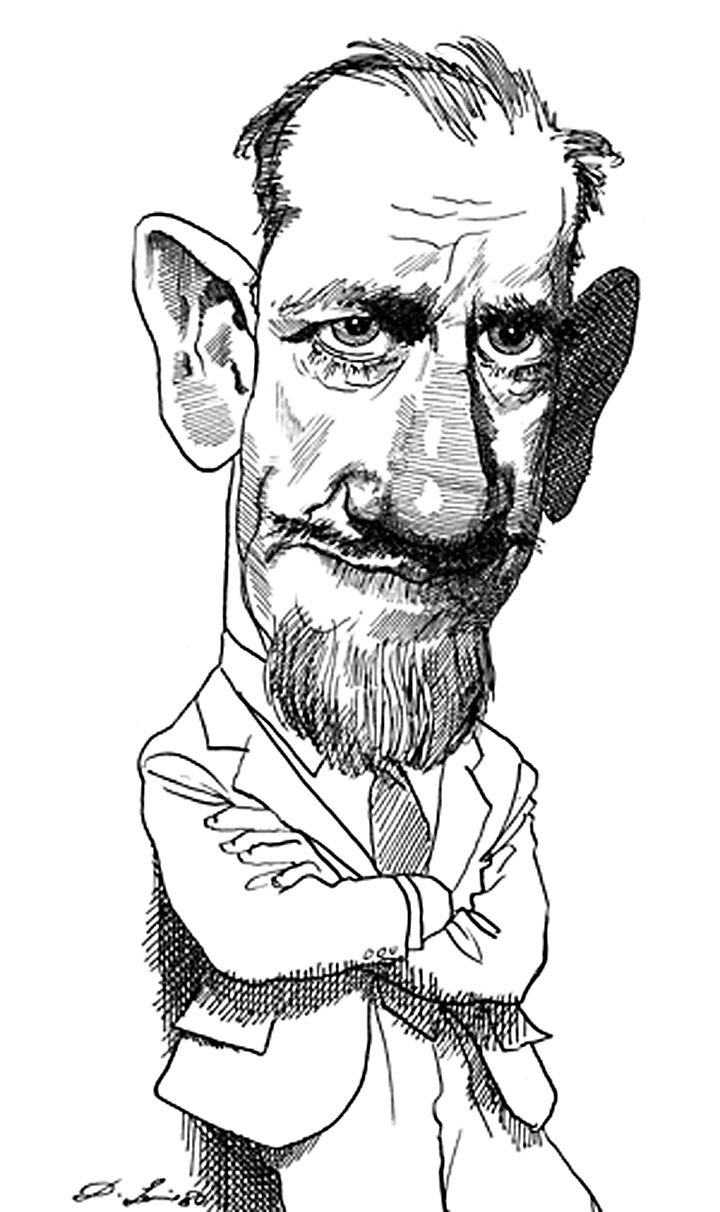

“Put More Steinbeck In” to Make Pipe Dream Succeed

Did casting cause the closing of Pipe Dream, the Broadway musical created by the dream team of Rodgers and Hammerstein from John Steinbeck’s novel Sweet Thursday? The movie star they counted on to carry the show, Steinbeck’s friend Henry Fonda, couldn’t sing and wasn’t cast. The opera star Helen Traubel couldn’t act but was, and that caused problems they should have foreseen. Urged on by Richard Rodgers, Julie Andrews signed up for My Fair Lady instead of Pipe Dream, proving that some advice is worth following. In a Playbill magazine piece published to coincide with the anniversary of the show’s opening on November 30, 1955, Bruce Pomahac argues that the fault for its failure lay not with its stars but with its creators. Rodgers and Hammerstein were white bread compared with Steinbeck, and their views on acceptability were not in alignment. By playing down “the more prurient aspects” of Steinbeck’s story, “R&H were doing what they did best,” with the predictable result that “Steinbeck felt Rodgers & Hammerstein had, as he put it, ‘turned my whore into a visiting nurse.’” According to Pomahac, the 2012 off-Broadway revival of Pipe Dream by City Center “provided us with the first real shot at what Pipe Dream might have been since it first played on Broadway in 1955.” According to Theodore Chapin, who heads the Rodgers and Hammerstein Organization, the adaptors who are waiting in the wings to bring it back agree on one thing. “Put more Steinbeck in” if you want to succeed on Broadway.

Caricature of John Steinbeck by David Levine.

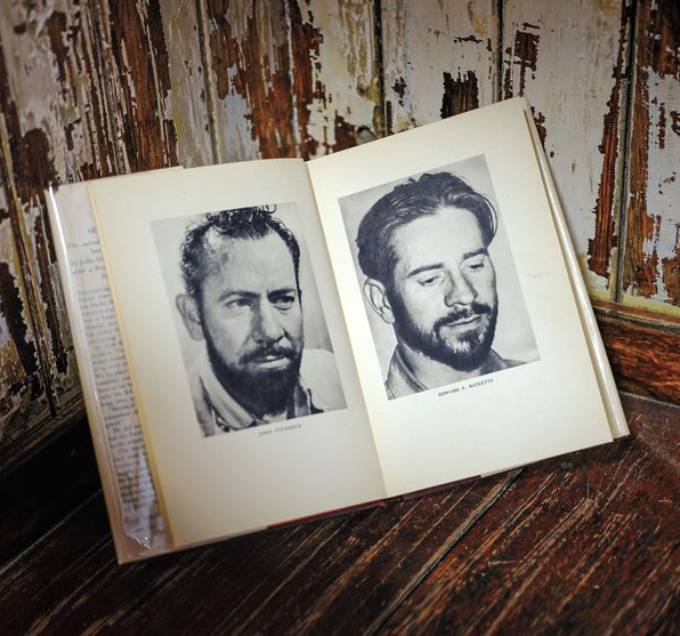

Cannery Row, Sea of Cortez Still Making Waves—On Both Sides of the Ocean—in 2019

Anticipating the 80th anniversary of John Steinbeck and Edward Ricketts’s expedition to the Sea of Cortez, and the 75th anniversary of the publication of Steinbeck’s novel Cannery Row, new profiles by or about a pair of writers born in England brilliantly reflect the role played by Steinbeck, Ricketts, and their free-range relationship in marrying literary imagination with marine biology to create modern ecological consciousness.

“John Steinbeck’s Epic Ocean Voyage Rewrote the Rules of Ecology”—a thoroughly researched and well-written feature by Richard Grant in the September 2019 issue of Smithsonian Magazine—recounts the 1940 journey that resulted in Sea of Cortez, the 1941 book co-authored by Steinbeck and Ricketts, and the ambitious project to restore The Western Flyer, the boat they used for their “voyage of discovery” to the waters and shores of Baja California. The fact-filled text by Grant, a British journalist based in Mississippi, is creatively complemented by photographs (like the one above) by Ian C. Bates, who lives near Port Townsend, Washington, where work on The Western Flyer continues, with an eye toward relaunch off Cannery Row in 2020.

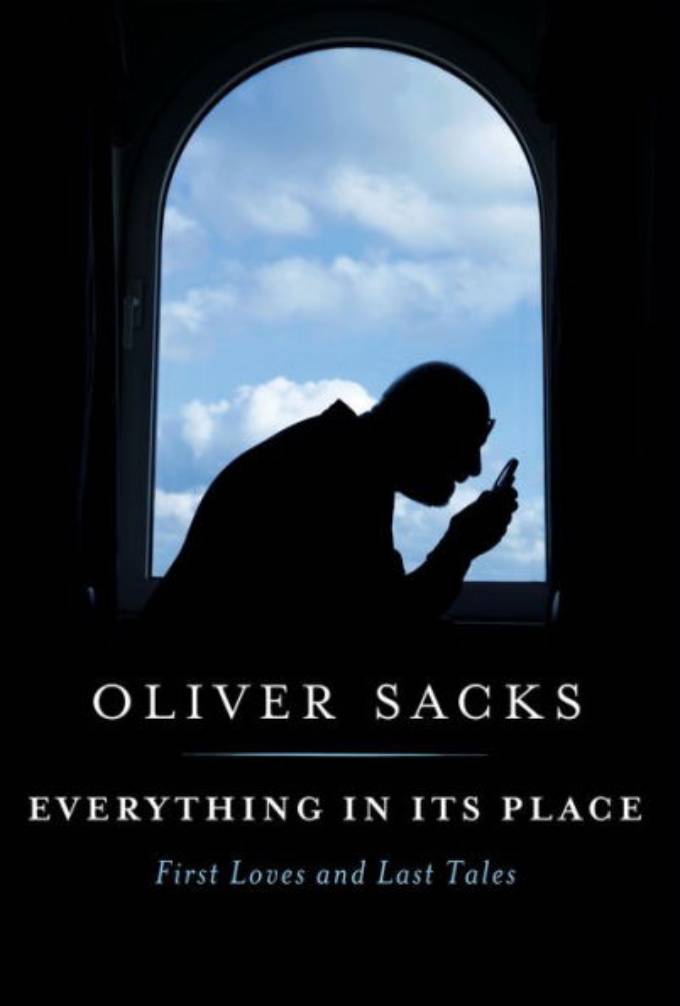

How Cannery Row Became California

The British literary naturalist and neurologist Oliver Sacks died from cancer in August of 2015, but the prolific polymath’s debt to Sea of Cortez, Cannery Row, and the Steinbeck-Ricketts collaboration is detailed in a pair of books published in the first half of 2019. Everything in Its Place: First Loves and Last Tales, the “final volume” of essays on life, death, and Planet Earth by Sacks (who published 15 books, including Musicophilia and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat) contains this paragraph about coming to Steinbeck country from Canada in 1960:

I was twenty-seven. I had arrived in North America a few months before and started out by hitchhiking across Canada, then down to California, which I had been in love with since I was a fifteen-year-old schoolboy in postwar London. California stood for John Muir, Muir Woods, Death Valley, Yosemite, the soaring landscapes of Ansel Adams, the lyrical paintings of Albert Bierstadt. It meant marine biology, Monterey, and “Doc,” the romantic marine biologist figure in Steinbeck’s Cannery Row.

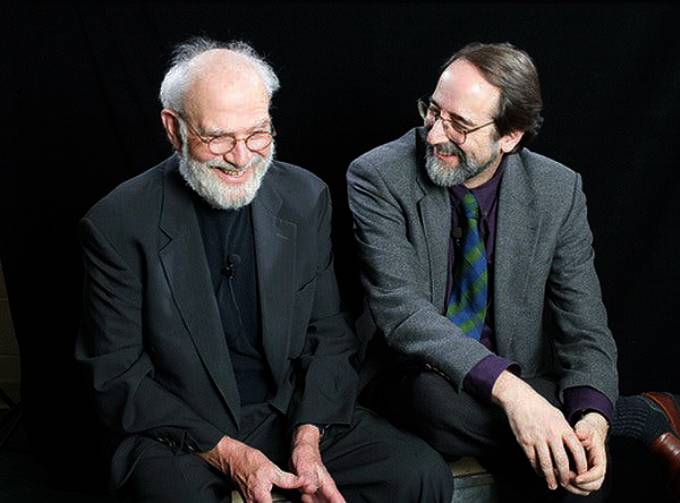

How Melville and Steinbeck Became Bookends

By 1982 Sacks had achieved fame as a medical renegade with literary genius for his book Awakenings, a suspenseful history of the set of post-encephalitic parkinsonian patients temporarily unfrozen by experimental L-dopa at the Bronx psychiatric hospital where Sacks worked, not without controversy, after he moved to New York. In 1982 Sacks was accompanied by the American journalist Lawrence Wechsler (at right in photo with Sacks) on a trip home to England for a New Yorker magazine profile of Sacks that never appeared. And How Are You, Dr. Sacks?—Wechsler’s memoir of the 35-year friendship that developed between the two men—records the following exchange, about influences, after a visit with Sacks’s 90-year-old father, a genial general practitioner in London who introduced his four precocious sons early (three became doctors) to the pleasures of science and reading:

Later, conversation with Oliver reverts to his childhood and school years. I ask him what sorts of books captivated him as a youth.

“Moby-Dick,” he replies, without a moment’s hesitation. “What can you say about Moby-Dick? There’s Shakespeare and there’s Moby-Dick and that’s that.

“We liked Cannery Row and Sea of Cortez, for the marine biology.” (Funny that, as bookends go: Moby-Dick and Cannery Row.)

Shakespeare, Melville, and marine biology also fired John Steinbeck’s mind. As bookends go, Oliver Sacks and Smithsonian Magazine make splendid specimens of the exultation expected in 2020 around Sea of Cortez, Cannery Row, and the marriage of marine biology and literary imagination—on both sides of the Atlantic.

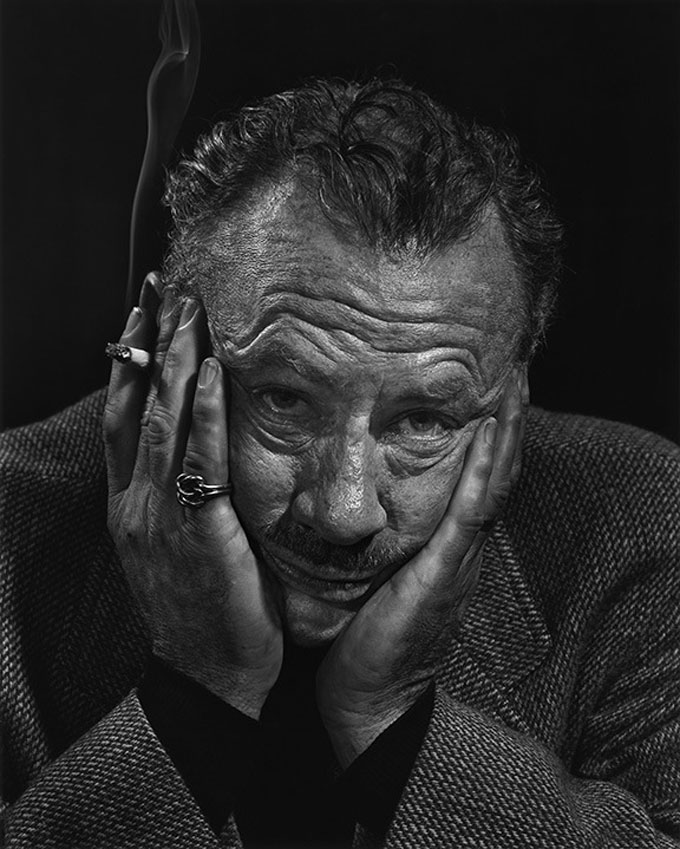

1954 Short Story by John Steinbeck Written in Paris Published by The Strand

The current issue of The Strand Magazine features a fun find—the English version of a whimsically satirical short story John Steinbeck wrote for the Paris paper Le Figaro, where it appeared on July 31, 1954 as Les Puces sympathiques. An expression of the Gallic wit exemplified by Steinbeck’s 1936 short story Saint Katy the Virgin and his 1957 novel The Short Reign of Pippin IV, “The Amiable Fleas” recounts a tragic-comic contretemps involving Monsieur Amité, a nervous French chef, and Apollo, his temperamental cat. The tongue-in-cheek item about the publication of the short story in today’s Guardian newspaper—“Crêpes of wrath: unknown John Steinbeck tale of a chef discovered”—quotes this understatement by the magazine’s enterprising editor, Andrew Gulli: “Don’t expect to read something dramatic in the vein of Grapes of Wrath.” According to The Guardian, Gulli found the manuscript among the Steinbeck holdings at the University of Texas, where he also came across the typescript of the Steinbeck sketch titled “With Your Wings”—written for radio broadcast in 1943-44 and published by The Strand in 2014. The Yousuf Karsh photograph above was taken at the Steinbecks’ residence in Paris about the time Steinbeck was writing “The Amiable Fleas” for Le Figaro, where he was a regular contributor, frequent interviewee, and favorite American.