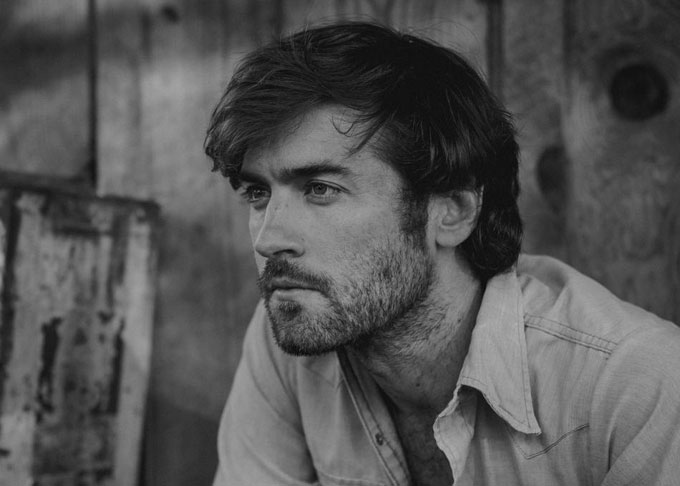

John Craigie speaks from experience about the title of his recently released tour recording John Craigie Live: Opening for Steinbeck. The soft-spoken West Coast singer-songwriter explains that performing as a warm-up act is like “having to read a short story by another author before getting to a work by John Steinbeck,” an artist who understood the perils of playing second fiddle. A born-and-bred Californian with the face of a sweet Tom Joad and the voice of a young Woody Guthrie, Craigie combines folk music, stand-up comedy, and situational storytelling to elicit the kind of audience response espoused by Steinbeck from listeners—to judge from the live recording—who are with him all the way on the perils of presidents named Trump and books named Leviticus. “The storytelling enables listeners to relate,” says Craigie, who majored in math at UC-Santa Cruz and got his start singing and playing in a band called Pond Rock. “Really good music doesn’t make you feel good,” he adds, echoing John Steinbeck on why he wrote fiction. “It makes you feel like you’re not alone.” Sample the track, then buy a signed CD of John Craigie Live: Opening for Steinbeck. (Photo of John Craigie by Bradley Cox)

John Craigie speaks from experience about the title of his recently released tour recording John Craigie Live: Opening for Steinbeck. The soft-spoken West Coast singer-songwriter explains that performing as a warm-up act is like “having to read a short story by another author before getting to a work by John Steinbeck,” an artist who understood the perils of playing second fiddle. A born-and-bred Californian with the face of a sweet Tom Joad and the voice of a young Woody Guthrie, Craigie combines folk music, stand-up comedy, and situational storytelling to elicit the kind of audience response espoused by Steinbeck from listeners—to judge from the live recording—who are with him all the way on the perils of presidents named Trump and books named Leviticus. “The storytelling enables listeners to relate,” says Craigie, who majored in math at UC-Santa Cruz and got his start singing and playing in a band called Pond Rock. “Really good music doesn’t make you feel good,” he adds, echoing John Steinbeck on why he wrote fiction. “It makes you feel like you’re not alone.” Sample the track, then buy a signed CD of John Craigie Live: Opening for Steinbeck. (Photo of John Craigie by Bradley Cox)