The principal writer and executive producer of Damnation, a new dramatic series premiering November 7 on USA Network, has cited John Steinbeck and Dashiell Hammett to describe the show’s depiction of rich vs. poor and brother against brother in rural Iowa during the Great Depression. In an interview with the Cleveland, Ohio Plain Dealer, Tony Tost, the show’s creator, explained that “the world of John Steinbeck as presented in The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men and Cannery Row was a big influence, as was Dashiell Hammett’s first novel, Red Harvest.” An award-winning poet, essayist, and screenwriter from Springfield, Missouri, Tost earned a PhD in English from Duke University and lives in Los Angeles, where he was a writer and producer for Longmire, a TV Western that ran for five seasons. The new show is “a little tricky to describe,” added Tost, the author of three volumes of poetry and a book of cultural criticism, Johnny Cash’s American Recordings (Continuum 2011). “It’s the Dust Bowl world. It has the feel of a Western. It has the strikebreaking. It has the religious themes. It has the pulp conspiratorial element. I’ve said it’s one part Clint Eastwood, one part John Steinbeck, one part James Ellroy.” The pilot episode will air tomorrow on USA Network at 10 p.m. EST. Damnation can also be viewed on Netflix, the entertainment giant headquartered in Los Gatos, where John Steinbeck wrote Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath.

New Yorker Says French Editor Uses American Literature, Travels with Charley to Explain America

The October 16 issue of New Yorker magazine reminds Steinbeck fans of their favorite author’s continued usefulness in understanding America and Americans. In a Talk of the Town item titled “Paris Postcard: In Search of America,” Lauren Collins reports that Francois Busnel, the host of a popular French television show about literature, is the new editor-in-chief of America, a French magazine “conceived to help French readers make sense of its namesake in the age of Trump.” Not surprisingly, Busnel looks to American literature to help explain Trump to his fellow countrymen. “We’re living in a profoundly novelistic era,” Busnel says, adding that Travels with Charley remains his favorite book about America and Americans in any age.

The Grapes of Wrath Inspires Lancaster Singer-Songwriter

A young singer-songwriter in Lancaster, Pennsylvania recently wrote a song inspired by The Grapes of Wrath, joining a line of Steinbeck-loving singer-songwriters stretching all the way back to Woodie Guthrie. Jenelle Janci, staff writer for Lancaster Online, notes the most recent visitation of the Grapes of Wrath muse in her July 5 profile of Sean Cox, a popular club and wedding musician who recently cut his first solo record. “Letters to the Light”—the set Cox sang for his recent solo debut at a downtown Lancaster, Pennsylvania venue—sounds very different from the punk and garage-band music Janci says the enterprising singer-songwriter performed as a teenager. Steinbeck, an author with eclectic musical tastes who admired artistic courage, would approve.

Photo of Sean Cox by Joey Ulrich courtesy WITF.

The New Florida Climate of No-Nothing Culture Rejects The Grapes of Wrath: Satire

Frank Cerabino, the humor writer for the Palm Beach Post newspaper best known for book-length put-downs of condo captains and crooked politicians, seized on The Grapes of Wrath to satirize Sean Hannity, intelligent design, and Florida climate deniers in a July 7 column—“Florida’s evolution to complainer’s paradise for public schools”—excoriating the new Florida law authorizing state hearing officers to consider requests from “any resident, regardless of whether he or she has children in the public school system, to instigate a formal challenge to any textbook, library book, novel, or other kind of instructional material used in a public school.” Here is the letter from an imaginary retiree with too much time on his hands demanding the removal of The Grapes of Wrath from a South Florida school district.

Dear Unbiased and Qualified Hearing Officer:

It has come to my attention that some public school libraries in this district contain the novel “Grapes of Wrath” by John Steinbeck, a well-known socialist who visited the Soviet Union in 1947 and espoused biased opinions about capitalism.

By allowing students to read Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath” you are exposing them to a work of art that shines a harsh light on American history and its ideals.

This is shameful, and obviously part of the school board’s liberal agenda. Which is why me and others in my morning Einstein’s Bagels discussion group hereby demand that unless you balance Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath” in school libraries with Sean Hannity’s inspiring book, “Let Freedom Ring: Winning the War over Liberalism” we will be requesting a public hearing.

We’re not putting up with the school district’s Saul Alinsky tactics!

Grapes of Wrath Parody Spoofs Steinbeck’s Style

John Steinbeck famously refused to let style dictate subject in his writing. So fans of The Grapes of Wrath could laugh without feeling guilty when they read “Excerpts from Steinbeck’s Novel About the 2013-17 California Drought” by Riane Konc, a pitch-perfect parody of the turtle scene from The Grapes of Wrath published online by The New Yorker. For great writers, imitation really is a form of flattery, and the humorous send-up of Steinbeck’s full-throated style from Konc, a youthful contributor to the magazine’s humor section, also manages a shout-out to the ecological truth embedded in Steinbeck’s greatest novel. Here’s a sample of paying tribute while making fun of a style John Steinbeck chose not to repeat, despite urging:

When 2015 was half gone, and the sun climbed high above the 405 and stayed, an In-N-Out wrapper blew down the highway like a tumbleweed, and a land turtle lumbered onto the road and began to cross. . . . A woman screamed—something guttural, a noise she hadn’t made since Lindsey suggested that maybe they just pack up and try Brooklyn—and dashed into the road. She grabbed her turtle and screamed again, “Banksy!,” for that was his name. His name was Banksy, and he was a rescue, not that the man driving the Tesla would care to ask, or know the difference between a rescue turtle and one from a mall.

As they say in Brooklyn when recommending guilt-free pleasure: Enjoy.

Are British Newspapers Brighter? The Guardian Shines on Tortilla Flat

Word that readers of England’s Guardian newspaper chose Tortilla Flat and Cannery Row as books of the month for April pleased Steinbeck fans in and outside Great Britain. Steinbeck was an on-and-off-again journalist, and England became his temporary home twice—in 1943, when he was an American war correspondent in London, and in 1959, when he and his wife Elaine spent blissful months in a Somerset cottage that dated from Norman times. The Guardian’s current book-of-the-month blog also brings to mind Steinbeck’s critique of American war reporting from London as lazy, unintelligent, and banal. British newspapers vary in quality, but the best are brilliant in a literary way, and it’s hard to imagine an American paper giving Tortilla Flat the sustained, incisive treatment found in the Guardian blog. But American and British newspapers have one thing in common that Steinbeck, who could be cynical, would probably find unsurprising. The bad ones have caught tabloid fever, and the good ones have taken to asking for contributions to help them stay alive. Check out the Guardian newspaper’s blog on Tortilla Flat for evidence of British brilliance—and the lengths to which impecunity is driving intelligent journalism in Great Britain and the United States.

Guardian newspaper photograph of John Steinbeck from Rolls Press/Popperfoto/Getty.

The Guardian Tweets Great Britain’s Love for Steinbeck

Book lovers who read The Guardian, the long-lived daily newspaper in Great Britain with an international reach and reputation, picked two distinctively American novels by John Steinbeck—Tortilla Flat and Cannery Row—as this month’s selections for the paper’s reading group. “While Steinbeck himself was a popular choice as an author to help us celebrate the human spirit, winning many nominations for other books,” explained the book editor of The Guardian in a tweet to the group, “this feels like a good result, not least because both novels have their own special kind of glow and warmth.” John and Elaine Steinbeck—avid internationalists who had their pick of pleasant places—spent their happiest year in Great Britain, and literate Brits continue to return the love. “[Steinbeck’s] books still sell in their millions,” The Guardian added. “Here in the UK, Of Mice and Men is a staple of school exams, while The Grapes of Wrath remains a favourite around the world. Almost half a century after Steinbeck’s death, his reputation seems as solid and secure as any writer of his era.” Quite so.

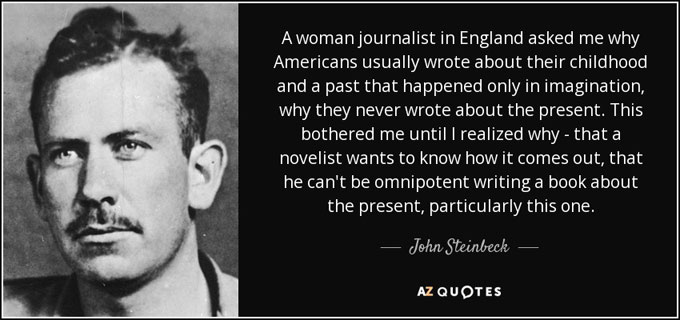

John Steinbeck Saw “Fake News” Coming When Donald Trump Was Still In Diapers

Did John Steinbeck discover “fake news” seven decades before President Donald Trump? Based on what he wrote about the mainstream media of his day in A Russian Journal, the author of The Grapes of Wrath came pretty close.

A Russian Journal is Steinbeck’s first-person journalistic account of the trip he took with photographer Robert Capa in 1947 to the war-battered Soviet Union. In Chapter 1, before he sets off for Russia, Steinbeck describes why he and Capa mistrusted the way the news in America was being gathered, edited, and disseminated by the dominant print and electronic media of their day. It has a familiar ring:

A Russian Journal is Steinbeck’s first-person journalistic account of the trip he took with photographer Robert Capa in 1947 to the war-battered Soviet Union. In Chapter 1, before he sets off for Russia, Steinbeck describes why he and Capa mistrusted the way the news in America was being gathered, edited, and disseminated by the dominant print and electronic media of their day. It has a familiar ring:

We were depressed, not so much by the news but by the handling of it. For news is no longer news, at least that part of it which draws the most attention. News has become a matter of punditry. A man sitting at a desk in Washington or New York reads the cables and rearranges them to fit his own mental pattern and his by-line. What we often read as news now is not news at all but the opinion of one of half a dozen pundits as to what that news means.

Steinbeck didn’t call it “fake news.” And he was complaining about bias in the media from a partisan New York liberal Democrat’s point of view. But anyone whose politics are not located in the dead center of the political spectrum today can feel his pain.

Claims of political bias or slanted news coverage from the left and right were nothing new when A Russian Journal was published in 1948, and they’ve been with us ever since. Conservatives have complained about the liberal East Coast media for half a century. In the babble of our Talk Radio/Cable News/Digital Age the mainstream media is criticized 24/7 from a thousand sane and insane places. No faction is happy with the spin of the news. In 2016 a Bernie supporter or a lifelong Nation magazine subscriber was just as likely to be unhappy with CNN’s coverage of the election as a member of the Tea Party.

The Mainstream Media’s Loss was Literature’s Gain

Though the young John Steinbeck was sacked as a New York City newspaper reporter because he couldn’t stop using his literary skills to improve on the facts, he was basically a journalist. A literary journalist. He had a love-hate for the journalism profession and its practitioners. He envied the ability of reporters to parachute into a strange place and quickly come up with the basic facts for a news story. But he also knew from experience that no journalist or writer—no matter how great—ever gets the whole story or captures more than just a glint of what really happened in a bank robbery, a presidential campaign, or a world war. He wrote this in A Russian Journal:

Capa came back with about four thousand negatives, and I with several hundred pages of notes. We have wondered how to set this trip down and, after much discussion, have decided to write it as it happened, day by day, experience by experience, and sight by sight, without departmentalizing. We shall write what we saw and heard. I know that this is contrary to a large part of modern journalism, but for that very reason it might be a relief. . . . This is just what happened to us. It is not the Russian story, but simply a Russian story.

Steinbeck’s journalism was super-subjective–sometimes to a fault. Russian Journal was his story about the backward, unfree, monstrous USSR he glimpsed in 1947, just as Travels with Charley was his subjective story about the 1960 America he saw on his iconic 10,000-mile road trip. Both books started out as works of nonfiction–as ambitious acts of serious, albeit personal, journalism. In Charley the many fictions Steinbeck slipped into his story about America overwhelmed the “true” facts, and after 50 years its publishers had to admit that it was so fictionalized Charley could not be considered a credible account of how he traveled or whom he really met.

Steinbeck’s journalism was super-subjective–sometimes to a fault. Russian Journal was his story about the backward, unfree, monstrous USSR he glimpsed in 1947, just as Travels with Charley was his subjective story about the 1960 America he saw on his iconic 10,000-mile road trip. Both books started out as works of nonfiction–as ambitious acts of serious, albeit personal, journalism. In Charley the many fictions Steinbeck slipped into his story about America overwhelmed the “true” facts, and after 50 years its publishers had to admit that it was so fictionalized Charley could not be considered a credible account of how he traveled or whom he really met.

A Russian Journal has suffered no such loss of credibility. It’s a great work of subjective journalism—a rare glimpse into a dark and alien world by a keen observer. Anyone teaching college students how to report and write in a precise, interesting, and powerful way would be smart to have them study how well Steinbeck did it—his way, and under trying circumstances .

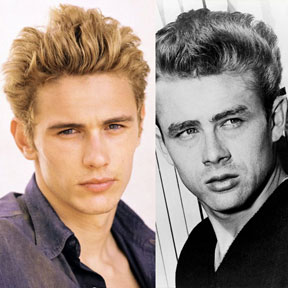

In Dubious Battle: A Film Festival Viewer Compares Steinbeck’s Novel and James Franco’s Movie Adaptation

Recently I attended the screening of James Franco’s movie adaptation of In Dubious Battle, Steinbeck’s 1936 strike novel, at the Mill Valley Film Festival in Marin County, California. Franco, who directs and acts in the motion picture, was present for the event, which I believe was the first time In Dubious Battle was screened publicly in this country. In his remarks Franco talked about casting and directing the film, and my general impression was that he believed he was being faithful to the theme of the novel.

As it happened, I was in the process of reading In Dubious Battle for an upcoming book club event in Monterey, California, where I live, and I noted changes in the film that surprised me, and that I felt violated Steinbeck’s intention in writing the novel. This itself is not unusual, since—as Steinbeck learned when Alfred Hitchcock mangled Lifeboat—some directors seem to think they can write a better story than the author. In the course of the Mill Valley Film Festival screening, I made a number of notes for my book club presentation comparing Franco’s movie and Steinbeck’s book.

The action of Chapters 1-4 includes Jim’s introduction to Mac, Joy, and Dick—California labor agitators sympathetic to the Communist Party—and their journey together to the Torgas Valley, the fictitious venue of In Dubious Battle. Although Harry Nilsen, a Communist Party figure, isn’t mentioned in the film, it follows Steinbeck’s story faithfully enough at the start, with one exception.

In James Franco’s treatment, Joe, the father of Lisa’s baby, abandons her when she becomes pregnant; in Steinbeck’s novel, he is still on the scene and appears in a minor role later in the action, in the course of which Lisa politely spurns Jim’s advances. In Franco’s version, Joe has to leave to make room for a romantic relationship: Jim loves Lisa, but chooses the cause over happiness with her. Hollywood always needs a romantic angle, even when that requires altering an author’s story and intent.

Chapters 5-8 in the novel present the development of plans for the strike, showing how Mac and Jim organize the effort and motivate the workers, and how Jim is increasingly radicalized under Mac’s guidance. Steinbeck’s character London, targeted as a leader by the strike organizers, is well cast in James Franco’s film. In Steinbeck’s version, Dan, an elderly apple picker, falls from the tree when the ladder he is using collapses. In the movie, Mac admits breaking the ladder so the workers will get mad and the cause will be advanced. For Mac, Dan is expendable. Unlike other changes made in the film, this one seems in character, and in harmony with Mac’s idea that ends justify means—contrary to what Steinbeck believed.

By contrast, the character of Joy, another expendable worker, is miscast. Steinbeck portrays Joy as a little guy who has been so badly beaten in the past that he may have become unhinged. In the course of a key scene in the novel, Joy is recognized by Mac and Jim while stepping off a train before being shot and killed, presumably by a vigilante sniper. In James Franco’s version, Joy is an old man, and he’s killed by a policeman after delivering a rousing speech—according to Mac, the most worthwhile thing Joy has ever done.

But the biggest negative change in characterization made by the film occurs in the presentation of Doc Burton, a key player who is described in Steinbeck’s novel as a fuzzy-cheeked young man. In James Franco’s version, he’s depicted as an older man and has a minor role. Most of the ideological dialog between Doc, Jim, and Mac—to me, the heart In Dubious Battle—has been eliminated.

In Steinbeck’s original, Mac and Jim make the argument that the strikers’ collective cause is more important than their individual lives and welfare. In response, Steinbeck’s Doc expresses doubt, raising questions about ends justifying means, violence begetting violence, and the dubious outcomes that flow from unexamined motives. This gives the story the skepticism and objectivity I think Steinbeck intended readers to take away from In Dubious Battle. Omitting Doc’s dialog, as James Franco does, robs the title of its point and encourages the viewer to take sides, like the director.

On the other hand, the portrayal of the deal made by the strikers with Anderson, the sympathetic farmer, is true to the novel, as is the interest expressed by the character Al in joining the Communist Party. In Steinbeck’s version, another grower’s house is torched, and Al survives. Here the movie is less clear, leaving me uncertain whether Anderson’s house is torched and Al is actually killed, or the rumor has been concocted to anger and motivate the strikers, like Dan’s death. Omitted entirely is the character of Dakin, the destruction of his truck, and the transfer of strike leadership to London that results.

Franco’s film, like Steinbeck’s novel, shows the strikers’ volatility, their rejection of the growers’ offer to employ London if they go back to work, and the sheriff’s threat to run them off Anderson’s land if they refuse. In the movie the tents where the workers live are white and new, and the breaking through of the barricade becomes a major scene. These changes, presumably made for visual and dramatic effect, don’t violate the spirit of Steinbeck’s story. The changes made in the story’s ending do.

In the novel Doc Burton’s absence is noted when London calls a meeting to decide whether the strikers will stay and fight or to leave, and a boy enters to report that Burton has been found in a ditch. Jim insists on going to Doc and is ambushed and shot. After carrying Jim back to camp, Mac says, “Comrades, he didn’t do anything for himself.” In the film it is Mac who is shot and killed, not Jim, and in a major reversal, it is Mac who becomes a martyr to the cause that Jim will carry on. As in the novel, we don’t know whether the strikers finally decide to fight or flee. Either way, however, they lose—out of a job and blacklisted if they leave; in jeopardy for their lives if they stay. Like the battle for labor rights, their immediate outcome is dubious. Whatever may happen to them personally, it is Mac who has put them a position of increased vulnerability. Absent the dialog written by Steinbeck for Doc Burton earlier in the story, this point is lost on viewers.

Steinbeck favored objectivity where James Franco takes sides, and the film concludes with a summary of pro-labor legislation enacted, supposedly as a result of In Dubious Battle, in the years that followed. To seems likelier to me that The Grapes of Wrath can be credited with influencing laws in favor of labor rights in the aftermath of the Great Depression.

James Franco is to be commended for producing, directing, and acting (as Mac) in this, the first movie adaptation made of In Dubious Battle since it was published 80 years ago. By downplaying Doc Burton and emphasizing Mac, however, Franco has substituted certitude for objectivity about ethics, motives, and outcomes in the long struggle for labor rights. This, to me, is his film’s most serious flaw.

In Dubious Battle Motion Picture by James Franco, Steinbeck Fan, Premieres

Movie reviews, like book reviews, sometimes influence audience behavior. But as John Steinbeck proved, loyal fans often ignore reviews if they really like an author or an actor. When James Franco’s motion picture adaptation of In Dubious Battle is released in the U.S. later this year, it’s doubtful that fans of Steinbeck or Franco will be affected one way or the other by the breathless reviews and red carpet hoopla In Dubious Battle received at film festivals in September. Reviews were mixed following the movie’s premiere at the Venice Film Festival, but Franco won points for making the first motion picture adaptation of Steinbeck’s 1936 strike novel, and that may be what fans appreciate most when they see the movie for themselves.

Movie reviews, like book reviews, sometimes influence audience behavior. But as John Steinbeck proved, loyal fans often ignore reviews if they really like an author or an actor. When James Franco’s motion picture adaptation of In Dubious Battle is released in the U.S. later this year, it’s doubtful that fans of Steinbeck or Franco will be affected one way or the other by the breathless reviews and red carpet hoopla In Dubious Battle received at film festivals in September. Reviews were mixed following the movie’s premiere at the Venice Film Festival, but Franco won points for making the first motion picture adaptation of Steinbeck’s 1936 strike novel, and that may be what fans appreciate most when they see the movie for themselves.

Reviews were mixed following the movie’s premiere at the Venice Film Festival, but Franco won points for making the first adapatation of Steinbeck’s 1936 strike novel.

Franco reread In Dubious Battle while rehearsing the role of George for the Broadway stage revival of Steinbeck’s 1937 play-novella Of Mice and Men, which has been filmed twice despite being, in Franco’s view, far less suited for the screen than the earlier book. During a press conference at the Deauville Film Festival following Venice, he explained that he decided to make In Dubious Battle now because “as a storyteller [I knew] it would make a great movie” and because its “central conflict had a topical resonance” he felt audiences would understand. That point seemed lost on critics at the Venice Film Festival: some got facts wrong about the novel; others ignored Franco’s intentions and concentrated on his personality and appearance. The response from critics may be more discerning when Franco’s movie opens at the film festival in Toronto, where reviewers won’t have to explain Steinbeck’s story to readers, or the parallels between Steinbeck’s time and today.

Rebel with a Cause: Filming Faulkner and Steinbeck

Whatever the final verdict on the film, Franco also deserves credit for both directing and acting (as Mac) and for attracting an amazing cast, including Bryan Cranston, Vincent d’Onofrio, Robert Duvall, Ed Harris, Sam Shepard, Selena Gomez, and Natt Wolff. Franco has appeared in dozens of movies, and he’s best known by mainstream moviegoers for playing slapstick characters in Animal House pictures like The Interview. But he has portrayed intelligent characters intelligently in highbrow films and acted and directed in adaptations of novels by Faulkner even harder to film than Steinbeck.

Whatever the final verdict on the film, Franco also deserves credit for both directing and acting (as Mac) and for attracting an amazing cast, including Bryan Cranston, Vincent d’Onofrio, Robert Duvall, Ed Harris, Sam Shepard, Selena Gomez, and Natt Wolff. Franco has appeared in dozens of movies, and he’s best known by mainstream moviegoers for playing slapstick characters in Animal House pictures like The Interview. But he has portrayed intelligent characters intelligently in highbrow films and acted and directed in adaptations of novels by Faulkner even harder to film than Steinbeck.

Whatever the final verdict on the film, Franco also deserves credit for both directing and acting (as Mac), and for attracting an amazing cast.

Like Faulkner, Steinbeck learned his limits when he tried to write for Hollywood, and he preferred to leave the job of adapting to specialists like Franco’s friend Matt Rager, the screenwriter Franco turns to when he makes literary movies, including biopics about authors. In several of these films Franco portrays tormented artistes from Steinbeck’s era—including Hart Crane, James Dean, and Alan Ginsburg—about whom Steinbeck could be critical. Franco grew up in Palo Alto, where Steinbeck went to college, and he writes fiction that appeals to the kind of reader who, unlike Steinbeck, is naturally attracted to Crane, Dean, and Ginsburg.. Like these figures, and like Steinbeck, Franco follows his own drummer as an artist, and his fans—like Steinbeck’s—respond in the same spirit. For American fans, Franco’s independence, courage, and passion for Steinbeck are cause enough to celebrate the making of In Dubious Battle, despite ill-informed movie reviews at foreign film festivals.