It’s a shame John Steinbeck didn’t live to see Saturday Night Live. The author of Of Mice and Men died in December 1968, six weeks after Richard Nixon was elected President; SNL debuted in 1975, fourteen months after Nixon resigned in disgrace. Much about Nixon’s America depressed Steinbeck, including Nixon’s party, but he kept his sense of humor and he understood the medium of television, Nixon’s undoing against Kennedy in 1960. If Steinbeck had lived longer he might have enjoyed SNL’s blend of comic relief and left-leaning satire, given his preference for politicians like Kennedy and Stevenson, the witty Democrat from Illinois defeated by Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956. Steinbeck critiqued Eisenhower’s thought (conventional), syntax (chaotic), and reading (cowboy fiction), so it’s easy to predict his reaction today to a worse-than-Eisenhower type like Donald Trump, or Rick Perry—brilliantly impersonated by Bill Hader, riffing on Of Mice and Men in this SNL sketch about the 2012 Republican candidate debate at which the man Trump made Secretary of Energy couldn’t remember the name of the federal department he now heads. If you need comic relief from Trump-induced depression, watch Bill Hader’s Rick Perry channel Lennie, with Mitt Romney as George at his side. Imagine John Steinbeck at your side and you’ll both die laughing.

Test Drive John Steinbeck’s America and Leave Feedback

Early in 1938, as Steinbeck began writing The Grapes of Wrath at his home in the mountains, he was nervous about doing justice to an American tragedy unfolding in real time: the flight of desperate farm families from the Dust Bowl states of Oklahoma, Texas, and Kansas to the Promised Land of California. “I’m trying to write history while it is happening,” he explained in a letter to his agent Elizabeth Otis, “and I don’t want to be wrong.” In the spring semester of 2017 I taught a course on John Steinbeck’s America that showed how right he was. It resulted in a new author website devoted to the world that John Steinbeck critiqued and created.

Twenty-three upperclassmen and two graduate students (one from Poland) enrolled for the course, offered in the University of Oklahoma’s College of Arts and Sciences. They came from Biology and Psychology and Letters as well as English and History, the departments in which it was cross-listed for credit. They read a variety of John Steinbeck’s works and discussed them within the context of American history and current events. They wrote papers on Steinbeck’s travels and wartime writing, works on stage and screen, Oklahoma, and East of Eden. They created the website introduced here for the first time for your comment.

The effort had excellent support. Mette Flynt, a PhD candidate in History, helped tighten prose, ensure accuracy in citations, and achieve consistency of language and layout. Paul Vieth, an MA student in History of Science, assisted with the Resources and Research page. Sarah Clayton—the University of Oklahoma Libraries staff member who won a national award for her innovative work with digital humanities course initiatives like this one—provided the class training in website construction using Omega, an open-source publishing platform. You can help by test driving the site and making suggestions.

Go to John Steinbeck’s America and give us your feedback in the comment box below.

John Steinbeck’s Women in Sag Harbor and Salinas

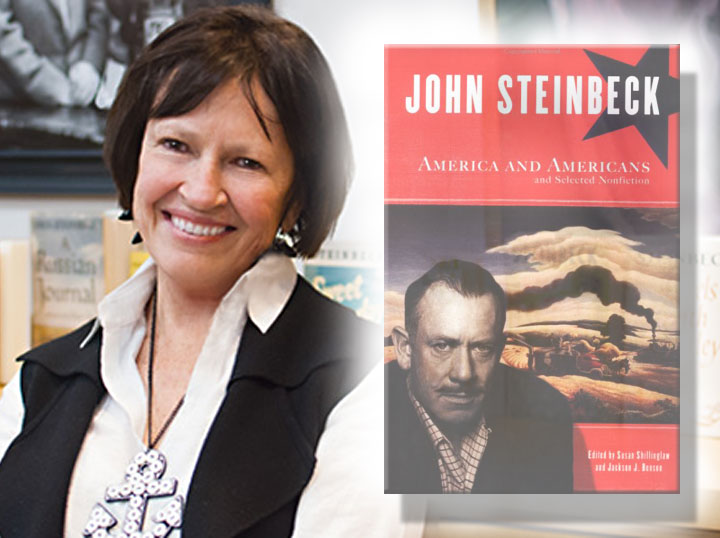

The village setting of The Winter of Our Discontent closely resembles Sag Harbor, the Long Island town where John Steinbeck liked to loaf and write, and the women in The Winter of Our Discontent reflect aspects of the women in Steinbeck’s personal life, the focus of the 2018 Steinbeck Festival in Salinas, the California town where the author of The Winter of Our Discontent grew up with a sister named Mary and a girl from church who went on to marry a man named Hawley. Susan Shillinglaw wrote the introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of The Winter of Our Discontent and conceived of the idea for this year’s Steinbeck festival, so there’s a pleasant symmetry to the May 18-20 celebration of the novel being planned in Sag Harbor, where Shillinglaw (in photo) will lead public discussion and the book will be read aloud, cover to cover, at Canio’s Cultural Café. Salinas and Sag Harbor were bookends in the life of John Steinbeck. So were the trio of Marys from Steinbeck’s family and the family of the novel’s hero Ethan Hawley—Steinbeck’s beloved sister; Ethan’s steadfast spouse, and the enlightened daughter who prevents his discontent from becoming despair. The temptress in Ethan Hawley’s tale also has a correlative in Steinbeck’s personal history. To find out who she was, sign up for the May 4-6 celebration of The Women of Steinbeck’s World and note whose name is missing from the honor roll. If Long Island is more convenient, show up for the May 18 talk by Susan Shillinglaw, the link between Steinbeck’s Sag Harbor and Salinas, and ask.

Not John Steinbeck’s View

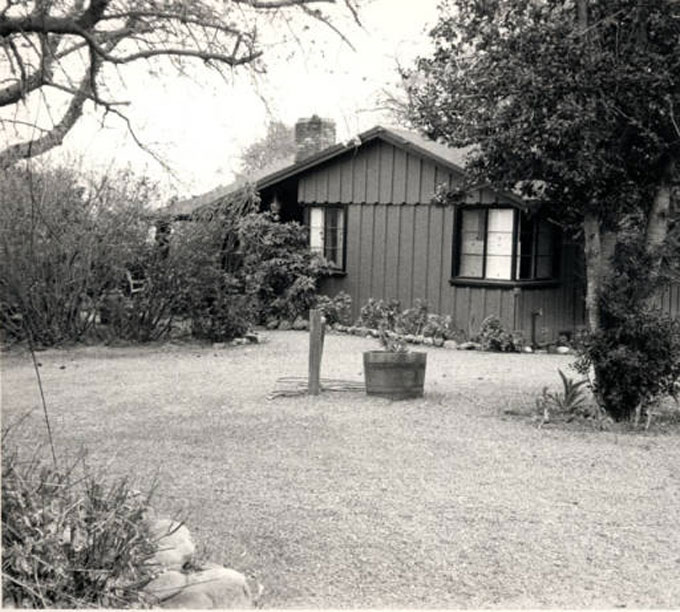

Purple sofas, 4,000 square feet, and an elevated view of midtown may make the New York apartment where John Steinbeck died in 1968 a bargain at $5 million, as asserted in the sale listing for 190 East 72nd Street, but the stark contrast with Steinbeck’s unvarnished view of the world in 1938 will not have escaped thoughtful readers of The Grapes of Wrath. A house is not a home if you’d rather be somewhere else, and Steinbeck preferred the little getaway he and his wife Elaine bought way out on Long Island because he preferred small towns, small houses, and doing his writing without a distracting view, however elevated. When Elaine Steinbeck died, new owners doubled the space of the apartment and added bedrooms and bathrooms (six of each) but kept the roll-top desk used by Steinbeck and offered as part of the sales pitch. But a sales picture is worth a thousand words. Compare the hard lines and assertive scale of the souped-up, for-sale living room, with its massive, grape-purple sofas and $5-million view, and the solitary appeal of the modest house where Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath—an unvarnished depiction of the stark contrast, then and now, between people with no home and those who live in glass houses but insist on throwing stones.

Photo of John Steinbeck’s Santa Cruz mountain home courtesy Los Gatos Public Library

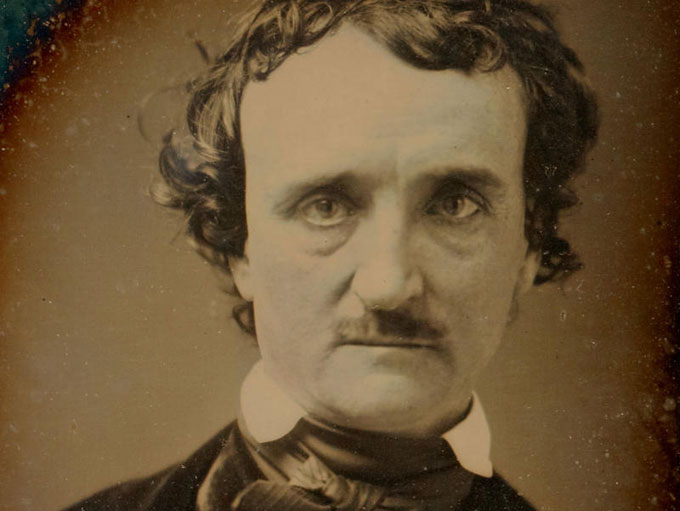

Picturing Edgar Allan Poe

As I was planning a trip from Virginia to California to visit my family in late February, I decided to add a two-day excursion to Salinas and the Steinbeck National Center. Shortly before I left, my eye was caught by a poetic tribute to Edgar Allan Poe at Steinbeck Now.com, an author website that had only recently come to my attention. Poe initially sparked my interest in closely examining great American authors. Now John Steinbeck has reignited my torch.

As I was planning a trip from Virginia to California to visit my family in late February, I decided to add a two-day excursion to Salinas and the Steinbeck National Center. Shortly before I left, my eye was caught by a poetic tribute to Edgar Allan Poe at Steinbeck Now.com, an author website that had only recently come to my attention. Poe initially sparked my interest in closely examining great American authors. Now John Steinbeck has reignited my torch.

Poe sparked my interest in closely examining great American authors. Steinbeck reignited my torch.

At my website LitChatte.com I have identified Poe as the first of a line of great American literary writers who portray American history imaginatively. While acknowledging that John Steinbeck continued the tradition, I was surprised to find a poem about Poe on an author website devoted to a writer best known for fiction. Though I can’t say that Roy Bentley’s poem is a fair portrayal of Poe—a pioneer who contributed to the advancement of American literature and the vocation of John Steinbeck—reading it reminded me that both writers were trashed by misinformed critics when their works first appeared and again when they died. Steinbeck was called a communist and a liar and his characters were deemed two-dimensional when The Grapes of Wrath was published. At the National Steinbeck Center I learned that copies were burned in Salinas and banned from schools and libraries around America, despite Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize.

I was surprised to find a poem about Poe on an author website devoted to a writer best known for fiction.

Similarly, Poe’s character and work were maligned by critics in his day, most harshly by Rufus Griswold—a contemporary who served as one of Poe’s principal editors—in The Poets and Poetry of America, an anthology edited by Griswold, and in an unsympathetic obituary of Poe that Griswold wrote under a pseudonym. The existing tension between the two men was exacerbated when Poe took exception to Griswold’s inclusion and omission of certain poets after the anthology appeared in 1842. Griswold retaliated by trashing Poe’s personal life in the October 9, 1849 New York Daily Tribune obituary he signed “Ludwig.”

Like Steinbeck, Poe’s character and work were maligned by critics in his day, most harshly by Rufus Griswold.

It didn’t take much detective work to determine that “Ludwig” was Griswold, a conniver who gained a stranglehold on future publication of Poe’s work (by usurping the role of Poe’s literary executor from Poe’s living relatives) and who damaged Poe’s reputation by falsely claiming that he “had few friends.” Halfheartedly conceding that “literary art has lost one of its most brilliant but erratic stars,” Griswold’s obituary portrayed Poe as a vagabond who moved pointlessly between Baltimore, Richmond, New York, and Philadelphia, even though Griswold worked at different times in the same cities—the only literary centers where a struggling writer (or editor) could hope to make a living in the first half of the 19th century.

Griswold’s obituary portrayed Poe as a vagabond who moved pointlessly between the only literary centers where a struggling writer could hope to make a living.

With each move, Poe developed an essential pillar of his versatile career as a professional writer, one which became a vocational model for later authors, like Steinbeck and Twain, who used their journalism to inform and inspire their literary creations. Griswold’s “Ludwig” obituary also spread the myth that Poe was a hopeless alcoholic and a madman, and it predicted that neither he or his writing would be long remembered. Time has disproved Griswold’s prophecy, and Griswold’s claims about Poe’s character and behavior have been discredited by serious scholars, though unwitting writers continue to base their assumptions about Poe on Griswold’s intentional misdirection.

With each move, Poe developed an essential pillar of his versatile career as a professional writer who used journalism to inform literary creation.

Reliable information can be found at the author website founded by the Poe Society, which points the reader to The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe, by Dwight Thomas and David Jackson. A comprehensive account of Poe’s professional and personal activities, it documents Poe’s friendships, and the position of respect he held in social circles where he was known. Though Poe wrote masterpieces of horror, he wasn’t mad, and the state of inebriation noted by others may well have been caused by acute sensitivity to alcohol, small amounts of which made him sick and appear drunk. Poe’s drinking was limited to social situations where gentlemen were expected to imbibe. A disciplined writer (there are no credible accounts of drinking while writing), Poe was devoted to his young wife Virginia, whose death a few years before his own contributed to his emotional and physical deterioration.

Though Poe wrote masterpieces of horror, he wasn’t mad, and the state of inebriation noted by others may have been caused by acute sensitivity to alcohol.

The true picture of Poe’s life explains why the poem at SteinbeckNow.com concerned me. It opens by suggesting that Poe could or would have downed “thirteen insipid whiskeys,” a preposterous proposition, despite the clever pun on “insipid.” (From what we know about his clinical condition, it’s likely he would become disoriented after the first drink and pass out after the second.) The elusive line “A joke is to say what its poets are to America” reflects a viewpoint advanced by Griswold in his anthology, and the reference to Poe’s strained relationship with his “foster father” John Allan, who “left him nothing,” repeats a misconception about Poe’s later behavior. Having dropped Allan’s name, he worked hard to provide for himself and his wife. He was prolific and his work sold well abroad. But lax copyright laws failed to protect writers’ interests in 19th century America, and Poe suffered the consequences.

Poe was prolific and his work sold well abroad. But lax copyright laws failed to protect writers’ interests in 19th century America, and Poe suffered the consequences.

Mark Twain learned from Poe’s experience and eventually self-published. Copyright laws improved in the 20th century, and writers like John Steinbeck (who also had a more supportive father) lived to achieve the financial security denied to Poe. Roy Bentley’s poem may have been intended as a tribute, but it fails to reflect the facts of Poe’s life, or Poe’s contribution to the progress of American literature. Instead of shedding new light on a sympathetic subject, it continues the slight to Poe’s reputation consciously created by Rufus Griswold, who knew that “a story will circulate” once it’s invented. Though eloquent, the last line of the poem (“If God exists, it isn’t to love poets”) regrettably reinforces that unfortunate conclusion.

Why We Don’t Delete Facebook But You Should

If the medium is the message, what does Facebook’s demeanor say about its dependent users? I don’t have boundaries—or enough to do to fill my time? I don’t have real friends, so pokes, shares and likes from fake ones fill my need to feel in touch? I don’t care if they sell my information because convenience is more important to me than privacy? Much as wish we could, we won’t delete Facebook from this website’s social media menu because some readers still use it to receive weekly post updates. But if you’ve tried reaching out to us there, we apologize for the inconvenience. We don’t respond to pokes and messages because we never liked the look and feel of the platform, or its potential for addiction and abuse. As explained in today’s report in The Hill on Facebook’s misappropriation of user data, recent events have confirmed our worst suspicions. If you decide to delete Facebook in protest, SteinbeckNow.com applauds you. You’re sending a message that the author who always preferred privacy to convenience would no doubt approve. Let us know when you do . . . but don’t use Facebook.

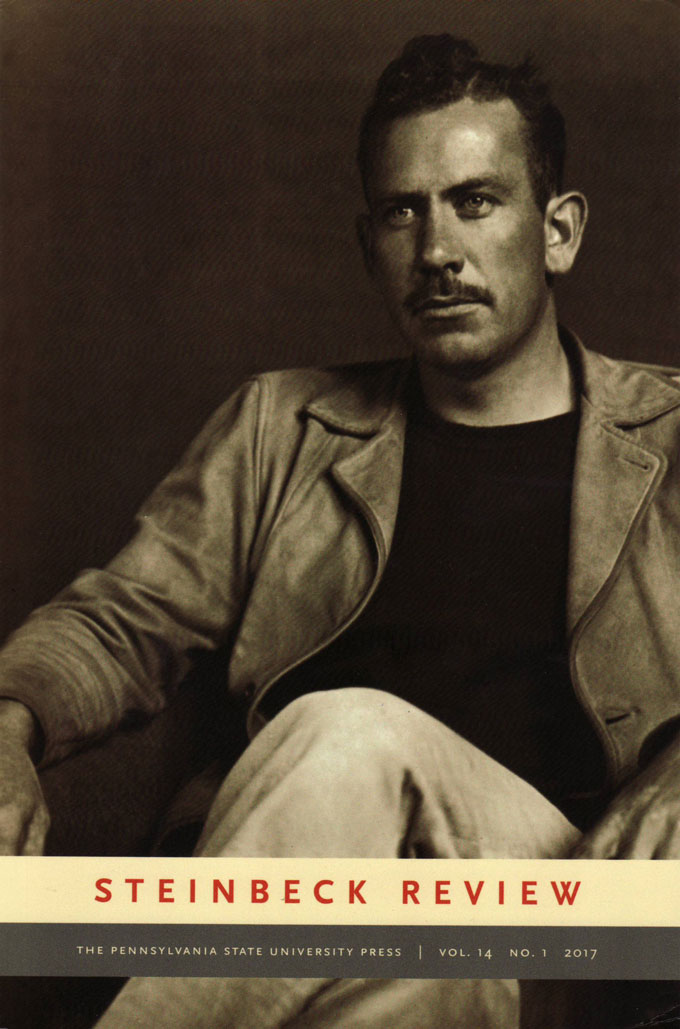

Steinbeck Review Expands Scope, Issues Call for Papers

Steinbeck Review, recently honored by listing in the international database Scopus, has expanded its purpose to specify that articles submitted for publication not only delight and instruct (à la Horace), but also illuminate issues, including the themes and problems treated in John Steinbeck’s work. This policy change reflects Steinbeck’s concern for truth and enlightenment, as well as for compassion and magnanimity, in books that warned readers of moral decline—and potential demise—in the America that Steinbeck loved. The subject of America and Americans preoccupied the writing of his final decade, and The Winter of Our Discontent, his last novel, acknowledged this didactic purpose: “Readers seeking to identify the fictional people and places here described would do better to inspect their own communities and search their own hearts, for this book is about a large part of America today.”

How to Submit Papers for the Spring 2018 Issue

In addition to more traditional scholarly articles, Steinbeck Review invites the submission of papers for the Spring 2018 issue that reflect John Steinbeck’s continued relevance for our time. All critical and theoretical approaches are welcome, as are essays focused on women’s and gender studies, rhetorical concerns, ecology and the environment, international appeal, and comparative studies. Poetry submitted for publication should deal with themes or places associated with Steinbeck’s life and work. Submit papers before January 15, 2018 through the journal’s automated online submission and peer review system at the Pennsylvania State University Press.

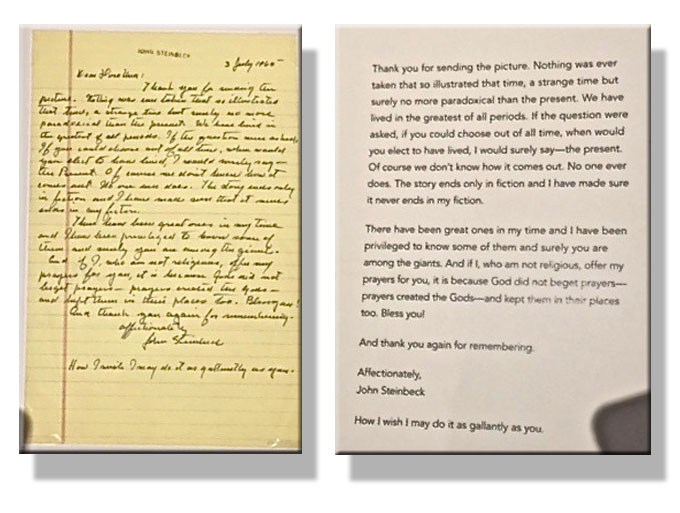

Bless You! John Steinbeck’s Letter to Dorothea Lange

Shortly before the show closed on August 27, my wife and I drove from our home in Salinas to the Oakland Museum of California to see Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing, an exhibit devoted to the documentary photographer whose images of the 1930s quickly became associated with John Steinbeck and The Grapes of Wrath. Like Steinbeck’s novel, Lange’s Great Depression pictures have become symbols of the suffering of farmland Americans displaced by joblessness, drought, and despair. Less familiar but equally powerful are the events recorded in Lange’s photos of Japanese-Americans “relocated” from their homes to internment camps after Pearl Harbor—an executive order signed by President Roosevelt that Steinbeck and Lange both questioned at the time. Lange’s internment images were so evocative, and so damning, that most of them were confiscated by the government and suppressed, even after the war. Also on display was the letter John Steinbeck wrote to Dorothea Lange on July 3, 1960, looking back on their friendship and the events of the Great Depression and ending with this deeply personal statement, half-confession and half-benediction: “And if I, who am not religious, offer my prayers for you, it is because God did not beget prayers—prayers created the Gods—and kept them in their places too. Bless you!”

John Steinbeck Talks about America & Americans Today

Tom Lorentzen, a retired nonprofit executive in Castro Valley, California, brought John Steinbeck back to life literally on August 24 at a private event billed as “John Steinbeck—in Search of America” and attended by 175 members of a San Francisco Bay Area social club. Impersonating Steinbeck at the age when Travels with Charley and America and Americans were written about a nation rocked by scandal and strife, Lorentzen employed an original idea to dramatize the imaginary conversation of Steinbeck—back from the dead—with Rich, a young logger encountered by the author in an Oregon redwood grove during the fabled road trip across the country from which Steinbeck said he had begun to feel alienated. Now 80, Rich uses a search engine time-travel device to conjure Steinbeck and pose the question he failed to ask when they met in the woods in 1961. What’s so great about America? Lorentzen (in photo) is a former board member of the National Institute of Museum Services. Like Steinbeck, who served on the board that became the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, he remains bullish on America’s future, despite problems that Steinbeck would recognize and acknowledge if, age 115, he were alive today.

A Travel Blogger Considers American Self-Identity on a Visit to Salinas, California

The recent visit my wife Elizabeth I made to Salinas, California included a stop at John Steinbeck’s boyhood home. It brought back a flood of memories, and it made me think about self-identity. That felt right in the moment because America’s sense of itself was a major concern of Steinbeck’s writing.

America’s sense of itself was a major concern of John Steinbeck’s writing.

When I was a boy I devoured Steinbeck’s books. By age 16 I knew I wanted to be a writer, and I spent hours copying passages from Steinbeck to get the hang of his style. Years later my brother John and I produced travel films and documentaries, and one of the films we made, California: A Tribute, featured a segment on John Steinbeck and the trips to California’s Central Valley that led him to write The Grapes of Wrath. Seeing the Steinbeck House reminded me of the outrage Steinbeck felt about the thousands of dispossessed families from the American Dust Bowl who had made the long trek to California in search of agricultural jobs and a better life, only to find themselves destitute, hungry, and homeless, ready to accept work at any pay so that they could survive and feed their children.

By age 16 I knew I wanted to be a writer, and I spent hours copying passages from Steinbeck to get the hang of his style.

On a broader scale, the visit to the Steinbeck House made me think about the course of our nation’s history, about the millions of dispossessed foreigners who came to our shores and borders, fleeing persecution and homelessness and poverty, in search of a better life for themselves and their families, just like John Steinbeck’s American refugees. Today we seem to be returning to the posture of the authorities in The Grapes of Wrath—denying rights, making arrests, and deporting men, women, and children, sometimes entire families who have already established themselves in our country. Once upon a time we opened our doors to immigrants. Now we’re closing them.

Today we seem to be returning to the posture of the authorities in “The Grapes of Wrath”—denying rights, making arrests, and deporting men, women, and children.

Certainly rules need to be established and followed with respect to immigration. But what is happening now goes beyond rules or regulations. Too many of us are attempting to retreat into a narrow self-identity, building walls against the tide of diversity that has been our distinguishing characteristic as a culture. Who are we as a nation and a people? The comfortable categories of the past are being challenged and shattered in other countries, too, and we feel the same threat to our self-identity that they do. Like John Steinbeck, however, I am optimistic that a new inclusiveness will emerge in the end—the sense of connection and commonality that Steinbeck’s characters achieve in the closing pages of The Grapes of Wrath. The world of the truly human family.