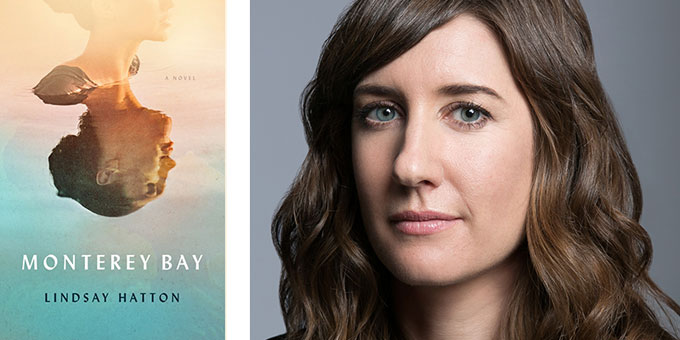

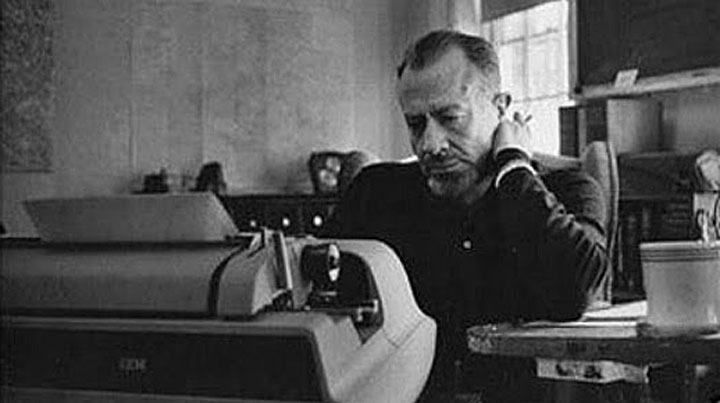

The main action of Monterey Bay, Lindsay Hatton’s debut novel, takes place in 1940, a big year for John Steinbeck, Ed Ricketts, and Monterey’s Cannery Row, where Hatton’s story is set. Waves churned up by the publication of The Grapes of Wrath in 1939 were swamping Steinbeck, who made his escape to the Sea of Cortez in the spring of 1940 with his friend Ed Ricketts, the marine biologist mythologized by Steinbeck’s 1945 novel Cannery Row. Hatton—who spent summers working at the Monterey Bay Aquarium on modern-day Cannery Row—leverages John Steinbeck’s predicament and Ed Ricketts’s reputation as a lover of women not his wife in her tale of an anti-ingenue’s coming of age among flawed men in an era less sexually prohibitive than our own. Other writers who have fictionalized events involving John Steinbeck, such as Steve Hauk, draw their characters exclusively from real life. Hatton—a resident of Cambridge, Massachusetts—mixes fantasy and reality to create Margot Fiske, a 15-year-old with chops and attitude who takes up with Ed Ricketts and clashes with John Steinbeck. Steinbeck employed a similar technique in his writing after Sea of Cortez (1941), notably Cannery Row and East of Eden. Readers didn’t seem to mind then, and they probably won’t now. Read a full review to learn more about Lindsay Hatton and Monterey Bay.

Nancy Hauk, Popular Pacific Grove Visual Artist, Mourned

Nancy Hauk, the popular Pacific Grove, California visual artist for whom the Pacific Grove Library’s art gallery is named, died on July 22 after a long illness. With her husband Steve Hauk, the author of short stories based on true events from the life of John Steinbeck, she owned and operated Hauk Fine Arts, the art gallery located near Holman’s department store, a Pacific Grove landmark celebrated in John Steinbeck’s fiction. She grew up in St. Louis, Missouri, and graduated with a degree in art history from Connecticut College before moving to Pacific Grove with her husband in the 1960s. Her watercolors—painted at home in California and on trips to France—were featured last year in a well-attended exhibition at the Pacific Grove Library, where John Steinbeck’s wife Carol is thought to have worked when the couple lived in Pacific Grove in the 1930s. Hauk Fine Arts specializes in the work of California artists from John Steinbeck’s era and is located near other local landmarks familiar to Steinbeck fans. These include the Steinbeck family cottage on 11th Street and the former home of Steinbeck’s friend Ed Ricketts, where the Hauks lived until Nancy moved to The Cottages, the Carmel assisted-living apartments where she died peacefully, surrounded by her husband with daughters Amy and Anne and mourned by friends and fans everywhere.

John Steinbeck in Los Gatos: The Progressive Politics Behind The Grapes of Wrath

Recently an enterprising Italian high school teacher named Enzo Sardarello blogged about John Steinbeck’s Los Gatos neighbor Charles Erskine Scott Wood, a Whitmanesque author and painter and an energetic advocate for progressive politics during the era leading up to the writing of The Grapes of Wrath. Before studying law in the East, Wood served as an infantry officer in the Nez Perce Indian war of 1877; as a defense attorney in Oregon and guru of progressive politics in Los Gatos he opposed U.S. imperialism, advocated for Indian rights, and espoused birth control, free thinking, and free love. Between 1925 and 1944, his powerful personality and Los Gatos home attracted a host of artists, writers, and celebrities, including Charlie Chaplin, Ansel Adams, and John Steinbeck. Sardarello’s post about this chapter in Steinbeck’s life is a reminder that international interest in The Grapes of Wrath—written in Los Gatos during the time Steinbeck knew Wood—continues today, and that Steinbeck had more congenial neighbors in Los Gatos when he lived there than Ruth Comfort Mitchell, the Republican novelist whose reactionary response to The Grapes of Wrath is the subject of a summer exhibit at the Los Gatos history museum.

John Steinbeck House in Salinas, California Receives Award from Trip Advisor Site

John Steinbeck won literary honors during his lifetime, including a Nobel Prize. Now the house where he was born and reared in Salinas, California has received a high accolade from TripAdvisor.com, one of the hospitality industry’s most heavily used consumer websites. People who visited the Steinbeck House restaurant and gift shop during the past 12 months rated their experience as “excellent” or “very good” frequently enough to earn Trip Advisor’s Certificate of Excellence for the thriving Salinas venue. John Steinbeck, who could be critical of business in his writing, would be gratified. Education and enjoyment, not money, motivated members of the Valley Guild to buy the Steinbeck home, restore it, and operate an intimate restaurant, staffed by a professional chef and volunteers servers, where answers to questions about Steinbeck come with the meal. Toni Bernardi, president of the nonprofit organization, explains: “We appreciate our guests and we all strive to honor the memory of John Steinbeck’s life and work.” Today honoring John Steinbeck turns out to be a good way to pay the bills—and garner praise from the hospitality industry—in Salinas, California.

Los Gatos History Museum Replays Republican Party’s Fight with John Steinbeck Over The Grapes of Wrath

Sometimes fences don’t make good neighbors. Take, for example, the town of Los Gatos, California, where John Steinbeck lived while writing The Grapes of Wrath. Ruth Comfort Mitchell, a California Republican Party stalwart and longtime Los Gatos resident, made speeches against Steinbeck and rebutted his book with her own novel, Of Human Kindness, a whitewash of California agricultural practices in 1940. The wife of a Republican Party official who served in the state senate, Mitchell was a conservative advocate and author with a following, but she wrote her novel in a hurry, and her defense of Republican Party business values failed to win hearts and minds outside California. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt rode to Steinbeck’s defense, The Grapes of Wrath became a bestseller, and Mitchell’s book was largely forgotten—until now. NUMU, the art and history museum in downtown Los Gatos, recently revived the partisan war of words waged by Mitchell against Steinbeck 75 years ago in an exhibit of books, photos, and documents organized by Amy Long, curator of history. “Mitchell vs. Steinbeck” runs through October 13. Visit the NUMU website for hours of operation and directions to the Los Gatos Civic Center, located on Main Street across from Los Gatos High School, a 1925 landmark familiar to Steinbeck and his un-neighborly antagonist.

John Steinbeck Returns to American Literature Lineup (And to San Francisco)

Following an absence of four years, John Steinbeck will return to the annual program of the American Literature Association when the organization holds its May 26-29, 2016 conference in San Francisco, the city where Steinbeck spent time as a Stanford student and struggling writer. A coalition of academic societies devoted to American writers from the 18th century to the present, the American Literature Association—like Steinbeck—began in California. It was founded in San Diego, the site of the most recent conference that featured Steinbeck, and its membership includes societies devoted to American writers—Raymond Carver, Percival Everett, Robinson Jeffers, Jack Kerouac, Sinclair Lewis, Jack London, Frank Norris, William Saroyan, Wallace Stegner, Gertrude Stein, John Steinbeck, Mark Twain, Thornton Wilder—with a California connection. “Steinbeck in Salinas and Abroad,” the subject of the May 26 panel organized by the International Society of Steinbeck Scholars, will focus on historical, ethnic, and ethical aspects of Steinbeck’s life and writing. Register at the American Literature Association conference website.

$4.8 Million Gift to John Steinbeck Center Reported By San Jose Mercury News

The April 20, 2016 San Jose Mercury News reports a record-breaking gift to San Jose State University by Martha Heasley Cox, a retired English professor with a love for John Steinbeck. In 1955—the year East of Eden became a movie—Cox arrived in San Jose from Arkansas with a new PhD to work at San Jose State, where she taught courses and organized conferences devoted to Steinbeck, wrote best-selling college textbooks, and invested the proceeds to support her passion for Steinbeck and her university. Her collection of books by and about Steinbeck became the core of the school’s Steinbeck Studies Center, the oldest academic enterprise devoted to the author in America, and she provided start-up funding for the organization, which was named in her honor. According to the San Jose Mercury News story, $3.1 million of Cox’s posthumous gift will fund the center’s Steinbeck Fellows program for young writers, and $1 million will augment the endowment of a lecture series, also bearing her name, that brings major authors—including Norman Mailer, Toni Morrison, and Andre Dubus III—to the San Jose State University campus each year. The balance of Cox’s bequest will support an online database of Steinbeck materials. As noted by the Mercury News, her gift is the largest made by a faculty member in the school’s history.

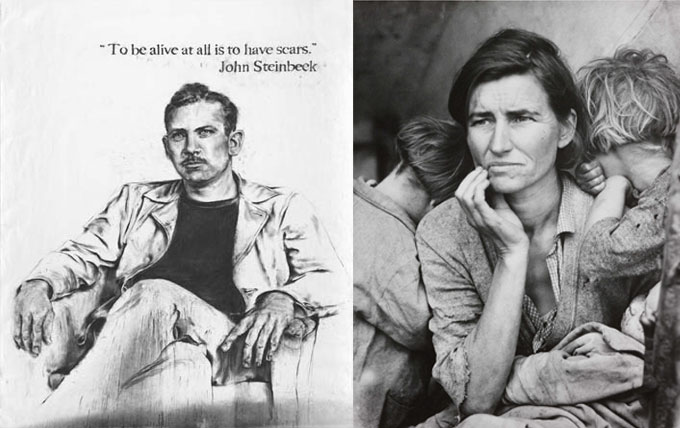

Santa Clara, California Drops The Ball on John Steinbeck And Dorothea Lange

John Steinbeck knew Dorothea Lange, the iconic Depression-Era photographer who documented the plight of itinerant farm workers like Steinbeck’s Joads, and Lange’s images illustrated the cover of Their Blood Is Strong, the collection of columns Steinbeck wrote about migrants in the run-up to The Grapes of Wrath. Eighty years later, Lange and Steinbeck have come together again in an unlikely place—the art collection on display at Levi’s Stadium, the $1 billion facility built recently in Santa Clara, California for the San Francisco 49ers football team. The irony of exhibiting Steinbeck’s portrait and Lange’s “Migrant Mothers” on the walls of a publicly subsidized sports palace seems lost upon the team’s owners and Santa Clara’s mayor, who resigned on February 9, hours after the 2016 Super Bowl was played at Levi’s Stadium.

The journalist Gabriel Thompson, a Steinbeck Fellow at San Jose State University, writes eloquently about the history of community organizing, and about today’s low-wage economy. An email he sent last week noted the jarring juxtaposition of Steinbeck and Lange with big-money sports on the walls of Levi’s Stadium, and it provided a link to the investigative piece he wrote for Slate about working as a food server during the Super Bowl. “The portrait hangs directly across from the office of the food service contractor that operates at Levi’s,” he said, adding that Lange’s “Migrant Mother” (originally titled “Pea Pickers”) is also on display. He included a link to a stadium PR story that makes this pitch for buying a box seat:

Gather 19 of your closest friends and rent a suite that gives you and your crew premium parking right next to the stadium, entry to Michael Mina’s Tailgate, upscale catering with an in-suite food and beverage credit, and access to the Trophy Club, where you’ll receive a complimentary glass of champagne and appetizers upon arrival. The suites are outfitted with comfy leather theater-style seats, Internet access and plenty of flat screen monitors to ensure you don’t miss any of the action. Prices vary by game but expect to shell out between $20,000 and $40,000 for the ultimate in VIP hospitality.

John Steinbeck, a critic of conspicuous consumption, celebrated common men and women in his writing. During college he worked for the Spreckels sugar company, which operated ranches in the rich agricultural area between King City and Santa Clara, California, south of San Francisco. Later, Santa Clara’s fragrant orchards gave way to development; today the city of 110,000 is home to tech giants including Intel, along with Santa Clara University, where a center for business ethics fronts a quiet entrance plaza anchored by the Mission Santa Clara church. Levi’s Stadium is across town, on land provided by the city not far from Intel and Mission College, a public institution. A local referendum to stop the San Francisco 49ers project failed, following a massive media and mail campaign and heavy lobbying by city leaders. According to news sources, controversy surrounding lost soccer fields—and suspicious side deals—continues to dog Santa Clara officials who went to bat for the project.

Steinbeck would recognize the present problem with Santa Clara. He wasn’t much of a sports fan, or civic booster, and his father became treasurer of Monterey County after the incumbent embezzled public funds. Today, Santa Clara residents are scratching their heads over the sudden resignation of their mayor, a former code-enforcement officer—an act, according to San Jose Mercury News columnist Scott Herhold, that disqualifies the ex-mayor from further office, “including secretary of his homeowners’ association.” According to the paper, the three women on the seven-member Santa Clara city council are asking hard questions about Levi’s Stadium, and the Hispanic city manager is complaining about racial discrimination.

Steinbeck would also recognize the unintentional irony—and the awful syntax—in another assertion, pulled from the PR piece quoted earlier, about the costly amenities at Levi’s Stadium:

Being that this stadium is located in the most-cultured half of California, an emphasis on art is a given. Spread throughout the elite Citrix Owners Club, the Brocade Club, BNY Mellon Club East and West and SAP Tower of suites, this collection, curated by Sports and The Arts specifically for Levi’s Stadium, is comprised of over 200 pieces of original artwork and 500 photographs that celebrate the history of the San Francisco 49ers as well as California’s stunning landscape. You’ll find charcoal sketches of notable figures such as John Steinbeck and Jack Kerouac as well as timeless psychedelics of the storied Fillmore made famous by Bill Graham. However, the portraits stadium-goers still pose next to the most are those of Joe Montana throwing to Jerry Rice and current quarterback Colin Kaepernick on the run.

When the city of Salinas wanted to name a school or library for John Steinbeck, he suggested choosing a bowling alley (or whorehouse) instead. For followers of the Levi’s Stadium story from Salinas and Monterey, there’s an upside to Santa Clara’s cluelessness about Steinbeck: Cannery Row may be tacky, and the National Steinbeck Center needs money, but neither place violates the spirit of John Steinbeck and Dorothea Lange like the San Francisco 49ers’ opulent new home in Santa Clara, California, where Steinbeck and Lange hang within view of noshing VIPs, high above ordinary football fans who can’t afford a five-figure seat.

Photo of Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California by Michael Fiola (Reuters).

“The Valley of the World”: John Steinbeck’s Salinas Valley in Color Photography Inspired by East of Eden

More than 60 years after it became a national bestseller, John Steinbeck’s novel East of Eden remains one of the writer’s most widely read works of fiction. Set in California’s Salinas Valley, where the author grew up and is buried, East of Eden recreates a turbulent era in American life, the period from the Civil War to World War I, through two generations of a pair of Salinas Valley families whose individual lives intersect dramatically during an era characterized by change and conflict in the Salinas Valley and on the world stage. In describing the novel’s setting as “the valley of the world,” John Steinbeck clearly meant East of Eden to be read as allegory, like the Old Testament story mirrored in its title, and as autobiography—intended, he said, for his two young sons, growing up far from the Salinas Valley after World War II. In 2010, the Steinbeck scholar Michael J. Meyer asked David A. Laws, a gifted photographer known for his bright images of John Steinbeck’s Salinas Valley, to take a series of photos to illustrate a book of literary essays on East of Eden. Meyer died in 2011, but the process of collecting and editing essays by various scholars of John Steinbeck was picked up and completed by Henry Veggian, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The result was East of Eden: New and Recent Essays, published by Editions Rodopi (now Brill) in 2013 and reviewed here.—Ed.

Images of the Salinas Valley Inspired by East of Eden

My contribution to East of Eden: New and Recent Essays appeared as a black-and-white photo essay—“Literary Landmarks of East of Eden”—comprised of 15 images that I look of locations around the Salinas Valley inspired by passages from John Steinbeck’s epic novel. The text I wrote remains the copyright of Rodopi, but I retained ownership of the following images, published here for the first time from my original color files. Although much has changed since John Steinbeck returned to his hometown in the early 1950s to recall the “sights and sounds, smells and colors” of the Salinas Valley that fill East of Eden, and even more since Adam Trask arrived in search of his own Eden, these images are recent examples of the scenes and settings that informed the author and that continue to convey the essence of those times. Page references quoting the novel are from the edition of East of Eden published by Penguin Books in 2002, John Steinbeck’s centennial.—David A. Laws

“I would like to write the story of this whole valley, of all the little towns and all the farms and ranches in the wilder hills.”—Steinbeck: A Life in Letters, ed. Elaine Steinbeck and Robert Wallsten (Penguin Books, 1976), p. 73

“The river mouth at Moss Landing was centuries ago the entrance to this long inland water.”—East of Eden, p. 4

“Then the hard, dry Spaniards came exploring through, greedy and realistic. . . . Of course they were religious people, and the men who could read and write, who kept the records and drew the maps, were the tough untiring priests who traveled with the soldiers.”—East of Eden, p. 6

“There were no springs, and the crust of topsoil was so thin that the flinty bones stuck through. Even the sagebrush struggled to exist, and the oaks were dwarfed from lack of moisture.”—East of Eden, p. 9

The Plaza Hall in San Juan Bautista played the role of the King City hotel in the 1981 “East of Eden” TV mini-series.

“One morning she complained of feeling ill and stayed in her room in the King City hotel while Adam drove into the country. He returned about five in the afternoon to find her nearly dead from loss of blood.”—East of Eden, p. 133

“Later Samuel and Adam walked down the oak-shadowed road to the entrance to the draw where they could look out at the Salinas Valley.”—East of Eden, p. 293

“They left the valley road and drove into the worn and rutted hills over a set of wheel tracks gullied by the winter rains. The horses strained into their collars and the buckboard rocked and swayed. The year had not been kind to the hills, and already in June they were dry.”—East of Eden, p. 137

“’This will be a valley of great richness one day. It could feed the world, and maybe it will.’”—East of Eden, p. 145

“In the country the repository of art and science was the school, and the schoolteacher shielded and carried the torch of learning and of beauty. The schoolhouse was the meeting place for music, for debate. The polls were set in the schoolhouse for elections. Social life, whether it was the crowning of a May queen, the eulogy to a dead president, or an all-night dance, could be held nowhere else.”—East of Eden, p. 146

“’I don’t know whether you noticed, but a little farther up the valley they’re planting windbreaks of gum trees. Eucalyptus—comes from Australia. They say the gums grow ten feet a year.’”—East of Eden, p. 164

“At eight-thirty on a Wednesday morning Kate walked up Main Street, climbed the stairs of the Monterey County Bank Building, and walked along the corridor until she found the door which said, ‘Dr. Wilde—Office Hours 11-2.’”—East of Eden, pp. 240-241

“The traditional dark cypresses wept around the edge of the cemetery, and white violets ran wild in the pathways. . . . The cold wind blew over the tombstones and cried in the cypresses.”—East of Eden, p. 309

“The ‘dobe house had entered its second decay. The great sala all along the front was half plastered, the line of white halfway around and then stopping, just as the workmen had left it ten years before. . . . A smell of mildew and of wet paper was in the air.”—East of Eden, pp. 342-343

“When Adam left Kate’s place he had over two hours to wait for the train back to King City. On an impulse he turned off Main Street and walked up Central Avenue to number 130, the high white house of Ernest Steinbeck. It was an immaculate and friendly house, grand enough but not pretentious, and it sat inside its white fence, surrounded by its clipped lawn, and roses and catoneasters lapped against its white walls.”—East of Eden, p. 382

“It’s a pleasant little stream that gurgles through the Alisal against the Gabilan Mountains on the east of the Salinas Valley. The water bumbles over round stones and washes the polished roots of the trees that hold it in.”—East of Eden, p. 589

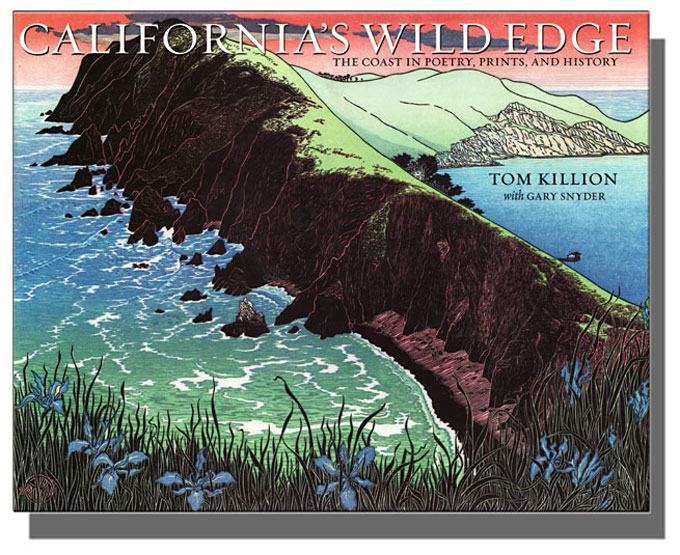

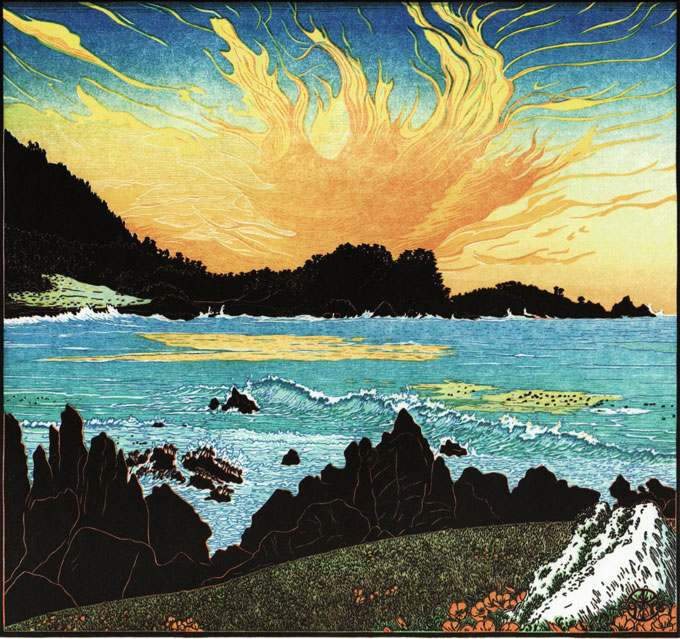

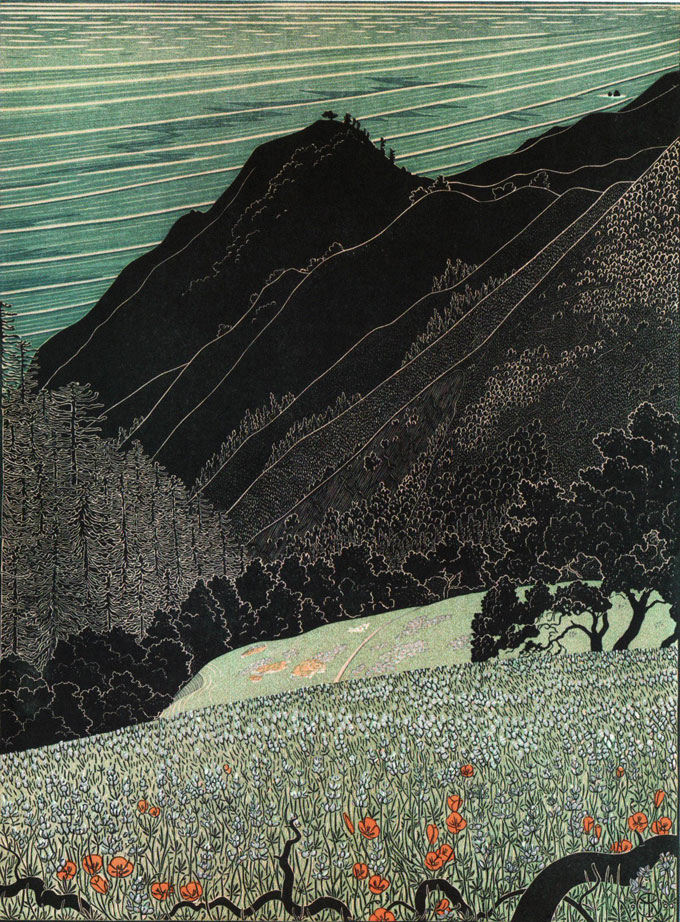

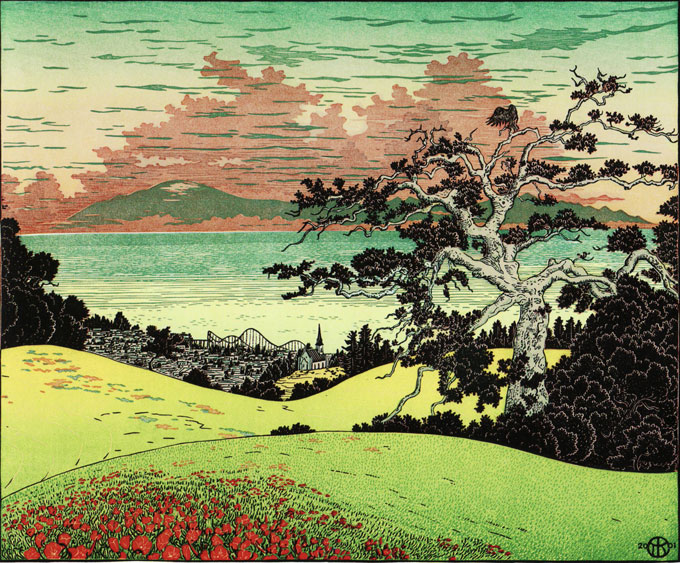

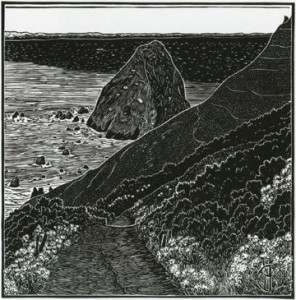

California’s Wild Edge: History, Poetry, and Art of Steinbeck’s California Coast

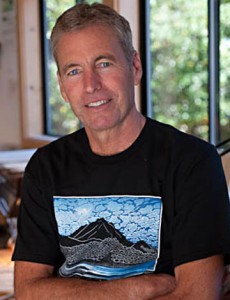

The Central California coast from Big Sur to Monterey Bay has become synonymous with John Steinbeck and Robinson Jeffers, the iconic poet of the California coast who lived in Carmel from 1913 until his death in 1962 and influenced Steinbeck’s writing in the 1930s. In California’s Wild Edge: The Coast in Poetry, Prints, and History, the California artist Tom Killion reinterprets the landscape of Jeffers and Steinbeck’s California coast in image, poetry, and narrative uniquely suited to today’s ecology-minded audience. Influenced by the East Coast artist and author Rockwell Kent, a contemporary of Jeffers and Steinbeck, and by the art of Japan, a country that Steinbeck wrote about and visited, Killion has developed over a period of four decades a distinctive style of wood and linocut printmaking that perfectly serves the subject of his most recent book. Like Kent, he is a visionary artist with an eye for arresting image, lyrical text, and their marriage in beautiful books with popular appeal. In California’s Wild Edge, the Pulitzer Prize-winning California poet Gary Snyder—Killion’s mentor, friend, and collaborator—continues to be an essential source of inspiration, ideas, and information about the mystical topography and extraordinary ecology of the state celebrated in Killion’s art.

The Perspective from Point Reyes

Rockwell Kent’s work was inspired by the rugged terrain of Monhegan Island, off the coast of Maine, where Kent lived from 1905 to 1910. Tom Killion has a similar relationship to Mount Tamalpais in California’s Marin County, where he grew up in the 1950s and 60s, and to Point Reyes, the isolated preserve on the Marin coast where he now lives and works. He became interested in book printing and poetry as a history major at the University of California, Santa Cruz in the 1970s. After graduation he traveled in Europe and Africa, returning to Santa Cruz to establish Quail Press before earning a PhD in African history at Stanford, the university Steinbeck attended but never finished. His first book, 28 Views of Mount Tamalpais, was published in 1975. Fortress Marin, his second, appeared in 1977, and The Coast of California: Point Reyes to Point Sur, his third, in 1979. During the 1980s he conducted historical research in Africa, administered a medical relief program in Sudan, traveled with nationalist rebels in Eritrea, and completed his fourth book, Walls: A Journey Across Three Continents (1990), which combines travel narrative with woodcut illustrations, as Rockwell Kent did in his books about wild, unpopulated places. In retrospect, Killion’s purpose as an emerging artist was clear early in his career: celebrating the human and natural ecology of people and places outside the mainstream of modern society, like Kent, an equally intrepid explorer.

Rockwell Kent’s work was inspired by the rugged terrain of Monhegan Island, off the coast of Maine, where Kent lived from 1905 to 1910. Tom Killion has a similar relationship to Mount Tamalpais in California’s Marin County, where he grew up in the 1950s and 60s, and to Point Reyes, the isolated preserve on the Marin coast where he now lives and works. He became interested in book printing and poetry as a history major at the University of California, Santa Cruz in the 1970s. After graduation he traveled in Europe and Africa, returning to Santa Cruz to establish Quail Press before earning a PhD in African history at Stanford, the university Steinbeck attended but never finished. His first book, 28 Views of Mount Tamalpais, was published in 1975. Fortress Marin, his second, appeared in 1977, and The Coast of California: Point Reyes to Point Sur, his third, in 1979. During the 1980s he conducted historical research in Africa, administered a medical relief program in Sudan, traveled with nationalist rebels in Eritrea, and completed his fourth book, Walls: A Journey Across Three Continents (1990), which combines travel narrative with woodcut illustrations, as Rockwell Kent did in his books about wild, unpopulated places. In retrospect, Killion’s purpose as an emerging artist was clear early in his career: celebrating the human and natural ecology of people and places outside the mainstream of modern society, like Kent, an equally intrepid explorer.

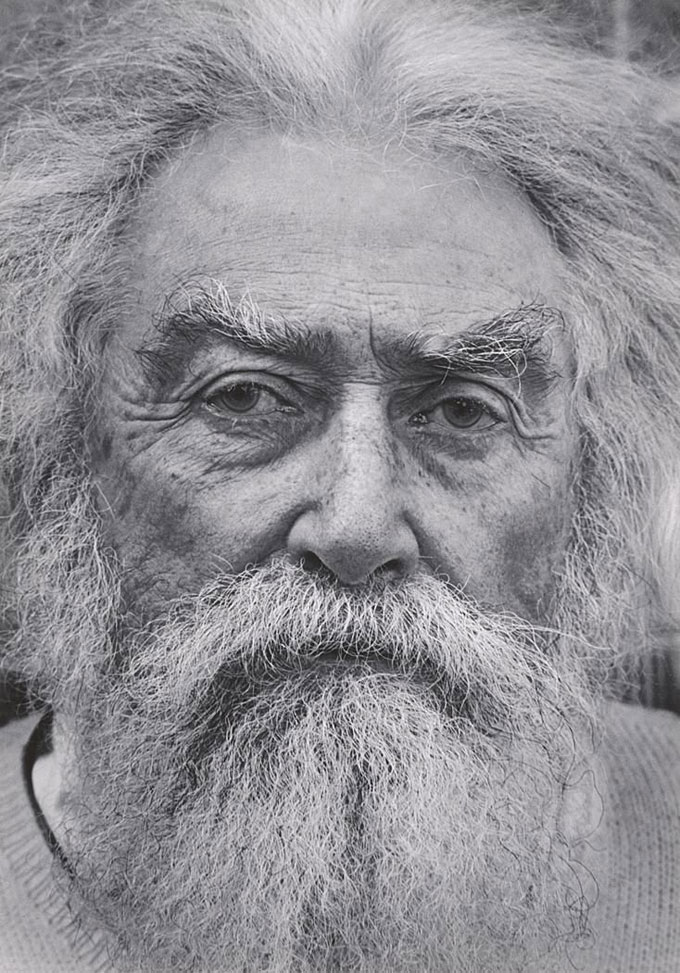

Gary Snyder, Poet Laureate of Deep Ecology

Killion taught history at Bowdoin College in Maine from 1990 to 1994, traveled to Eritrea as a Fulbright scholar in 1994, and returned to California in 1995 to teach at San Francisco State University. His collaboration with the San Francisco Renaissance writer and environmental activist Gary Snyder, “the poet laureate of deep ecology,” resulted in three volumes of art and text devoted to California’s legendary landscape, all published by San Francisco’s Heyday Books: The High Sierra of California (2002), Tamalpais Walking: Poetry, History, and Print (2009), and California’s Wild Edge (2015). Like John Steinbeck, Gary Snyder is a California native of Scots-Irish, German, and English ancestry with a worldwide reputation as an author and advocate on global issues. His progressive politics and activism, like Steinbeck’s, angered officials in Washington, D.C., and caused similar problems in his life. Like Steinbeck, he used his experience as a manual laborer in his early writing. Later he studied East Asian art and literature, lived and traveled in Japan, and became associated with the Beat movement centered in mid-century San Francisco. He received the 1975 Pulitzer Prize in poetry following the publication of Turtle Island, a book of poems and essays exploring humanity-in-nature from a holistic perspective similar to Steinbeck’s in Sea of Cortez. The spiritual dimension of environmentalism, East Asia, and the California coast and landscape informs his seven-decade career as a writer, one that bridges the generations of John Steinbeck and Tom Killion.

Killion taught history at Bowdoin College in Maine from 1990 to 1994, traveled to Eritrea as a Fulbright scholar in 1994, and returned to California in 1995 to teach at San Francisco State University. His collaboration with the San Francisco Renaissance writer and environmental activist Gary Snyder, “the poet laureate of deep ecology,” resulted in three volumes of art and text devoted to California’s legendary landscape, all published by San Francisco’s Heyday Books: The High Sierra of California (2002), Tamalpais Walking: Poetry, History, and Print (2009), and California’s Wild Edge (2015). Like John Steinbeck, Gary Snyder is a California native of Scots-Irish, German, and English ancestry with a worldwide reputation as an author and advocate on global issues. His progressive politics and activism, like Steinbeck’s, angered officials in Washington, D.C., and caused similar problems in his life. Like Steinbeck, he used his experience as a manual laborer in his early writing. Later he studied East Asian art and literature, lived and traveled in Japan, and became associated with the Beat movement centered in mid-century San Francisco. He received the 1975 Pulitzer Prize in poetry following the publication of Turtle Island, a book of poems and essays exploring humanity-in-nature from a holistic perspective similar to Steinbeck’s in Sea of Cortez. The spiritual dimension of environmentalism, East Asia, and the California coast and landscape informs his seven-decade career as a writer, one that bridges the generations of John Steinbeck and Tom Killion.

The California Coast from Big Sur to Cape Mendocino

The art of California’s Wild Edge, Killion and Snyder’s third collaboration, is breathtaking. Its text—a fusion of natural and human history, poems and journal entries by various writers, and personal memoir—constitutes a mini-course in California culture that delights and surprises at every turn. Before “Anglo-Californian” coastal poetry there was “the poetry of naming,” colonial Spain’s greatest contribution to California, and Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast, “the finest account of the coast ever written from the perspective of the sea.” The story of Big Sur, the most dramatic episode in the history of the California coast, is told through the life and writing of the colorful character Jaime de Angulo, and literary figures—including Robinson Jeffers, Jack London, and the poet George Sterling—attracted to Carmel, north of Big Sur, after the 1906 earthquake. Largely forgotten today, Sterling was born in Sag Harbor, New York—where Steinbeck later lived—and committed suicide by swallowing the cyanide pill he kept for the purpose, like Cathy in Steinbeck’s East of Eden, during a depression caused by his decline in fame and fortune in San Francisco. Not surprisingly, San Francisco serves as source, context, and symbol for much of Killion’s history of California coastal poetry, from the native peoples of the coast to Bret Harte and Robert Duncan, the “mystical poet and pioneer of gay civil rights” who, with Snyder and other San Francisco literary lights, created the city’s modern literary renaissance.

The art of California’s Wild Edge, Killion and Snyder’s third collaboration, is breathtaking. Its text—a fusion of natural and human history, poems and journal entries by various writers, and personal memoir—constitutes a mini-course in California culture that delights and surprises at every turn. Before “Anglo-Californian” coastal poetry there was “the poetry of naming,” colonial Spain’s greatest contribution to California, and Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast, “the finest account of the coast ever written from the perspective of the sea.” The story of Big Sur, the most dramatic episode in the history of the California coast, is told through the life and writing of the colorful character Jaime de Angulo, and literary figures—including Robinson Jeffers, Jack London, and the poet George Sterling—attracted to Carmel, north of Big Sur, after the 1906 earthquake. Largely forgotten today, Sterling was born in Sag Harbor, New York—where Steinbeck later lived—and committed suicide by swallowing the cyanide pill he kept for the purpose, like Cathy in Steinbeck’s East of Eden, during a depression caused by his decline in fame and fortune in San Francisco. Not surprisingly, San Francisco serves as source, context, and symbol for much of Killion’s history of California coastal poetry, from the native peoples of the coast to Bret Harte and Robert Duncan, the “mystical poet and pioneer of gay civil rights” who, with Snyder and other San Francisco literary lights, created the city’s modern literary renaissance.

But personal memories, not literary history, comprise the heart of Killion’s narrative—of a grandmother who left lonely Eureka, California for San Francisco in 1906 and survived the earthquake; of hiking Mount Tamalpais as a boy and biking from his parents’ home in Mill Valley as far north as Eureka and as far south as Santa Cruz; of helping clean up the 1971 Golden Gate oil spill that sparked Marin’s successful anti-development movement; of attending college in Santa Cruz, the embodiment of California coast culture, north and south; of returning to Marin County to live and work near unspoiled Point Reyes, “which projects father into the sea from the main axis of the California coast than any other point.” The “redwood coast” from Big Sur north to Humboldt Bay dominates Killion’s story because, he says, it’s less populated than Southern California and more dramatic. It’s the same California coast that engaged John Steinbeck in his much of his writing. The original setting of his second novel, To a God Unknown, was Mendocino County, and the 1955 movie adaptation of East of Eden was filmed in Mendocino—a stand-in, as Killion notes, for Monterey. Steinbeck liked to say he could take or leave the mountains, but had to live near the sea—the setting for his first novel, Cup of Gold, and for The Winter of Our Discontent, his last. Though neither novel is about California, each one has the unforgettable feel of the California coast between Santa Cruz and Big Sur where Steinbeck spent his happiest years—a rich source of history, poetry, and art from pre-Spanish times to the present. California’s Wild Edge captures the subject splendidly.

But personal memories, not literary history, comprise the heart of Killion’s narrative—of a grandmother who left lonely Eureka, California for San Francisco in 1906 and survived the earthquake; of hiking Mount Tamalpais as a boy and biking from his parents’ home in Mill Valley as far north as Eureka and as far south as Santa Cruz; of helping clean up the 1971 Golden Gate oil spill that sparked Marin’s successful anti-development movement; of attending college in Santa Cruz, the embodiment of California coast culture, north and south; of returning to Marin County to live and work near unspoiled Point Reyes, “which projects father into the sea from the main axis of the California coast than any other point.” The “redwood coast” from Big Sur north to Humboldt Bay dominates Killion’s story because, he says, it’s less populated than Southern California and more dramatic. It’s the same California coast that engaged John Steinbeck in his much of his writing. The original setting of his second novel, To a God Unknown, was Mendocino County, and the 1955 movie adaptation of East of Eden was filmed in Mendocino—a stand-in, as Killion notes, for Monterey. Steinbeck liked to say he could take or leave the mountains, but had to live near the sea—the setting for his first novel, Cup of Gold, and for The Winter of Our Discontent, his last. Though neither novel is about California, each one has the unforgettable feel of the California coast between Santa Cruz and Big Sur where Steinbeck spent his happiest years—a rich source of history, poetry, and art from pre-Spanish times to the present. California’s Wild Edge captures the subject splendidly.

Images from California’s Wild Edge ©Tom Killion 2015.

.