Salinas on Highway 101 in Monterey County is a piece of prose, an almost-odor, an unheard sound, a shade of gray, a pause, a reaction, an amnesia, dreaming of someplace else. Salinas is the have’s and have not’s, wood and brick and river and filled-in slough, cracked pavement and seedy lots and cemeteries, concrete buildings and rotting houses, churches, taco shops, and homeless shelters, and big empty box stores, and doctors’ offices and lawyers. Its inhabitants are, as the man once said, “Rotarians, Republicans, growers and shopkeepers,” by which he meant Somebodies. When the man looked through another peephole he said, “Sinners and vigilantes and racists and hypocrites,” and meant the same thing.

Salinas on Highway 101 in Monterey County is a piece of prose, an almost-odor, an unheard sound, a shade of gray, a pause, a reaction, an amnesia, dreaming of someplace else. Salinas is the have’s and have not’s, wood and brick and river and filled-in slough, cracked pavement and seedy lots and cemeteries, concrete buildings and rotting houses, churches, taco shops, and homeless shelters, and big empty box stores, and doctors’ offices and lawyers. Its inhabitants are, as the man once said, “Rotarians, Republicans, growers and shopkeepers,” by which he meant Somebodies. When the man looked through another peephole he said, “Sinners and vigilantes and racists and hypocrites,” and meant the same thing.

Salinas from Highway 101 Before Reading John Steinbeck

The August afternoon was hot and sticky when I took the Salinas exit from Highway 101 with my oldest college friend, an economics professor and Episcopal priest and gourmet cook from New York visiting Los Gatos, my new home 60 miles north of Salinas. I was a recent Florida transplant, and it was my first trip south on Highway 101 to Steinbeck Country. We knew Steinbeck was born in Salinas, but we weren’t looking for Steinbeck’s ghost. We weren’t even interested in Salinas. We were searching for the perfect artichoke, and the pilgrimage to Castroville and Watsonville—the heart of Salinas Valley’s artichoke industry—takes you through Salinas if you follow Highway 101, the safest route for the uninitiated.

I didn’t know it then, but later I would make the Highway 101 trek south to Salinas every Sunday to play the historic Aeolian-Skinner organ at John Steinbeck’s childhood Episcopal church. Retired from my day job in Silicon Valley and immersed in John Steinbeck’s writing, I decided to discover something new about John Steinbeck’s life in Salinas whenever I was in town. After researching church and town records of John Steinbeck’s upbringing, visiting his home and burial place, and interviewing Salinas residents about their town’s most famous son, I’ve learned a lot and formed an opinion. John Steinbeck was right: there wasn’t much to do in Salinas when he was growing up, and that hasn’t changed. But there is a great deal to doubt in Salinas about the legend of John Steinbeck perpetuated by local interests.

John Steinbeck’s View: Always Something to Do in Salinas

“Salinas was never a pretty town. It took a darkness from the swamps. The high gray fog hung over it and the ceaseless wind blew up the valley, cold and with a kind of desolate monotony. The mountains on both sides of the valley were beautiful, but Salinas was not and we knew it. Perhaps that is why a kind of violent assertiveness, an energy like the compensation for sin grew up in the town. The town motto, given by a reporter ahead of his time, was: ‘Salinas is.’ I don’t know what that means, but there is no doubt of its compelling tone.”

—John Steinbeck, “Always Something to Do in Salinas”

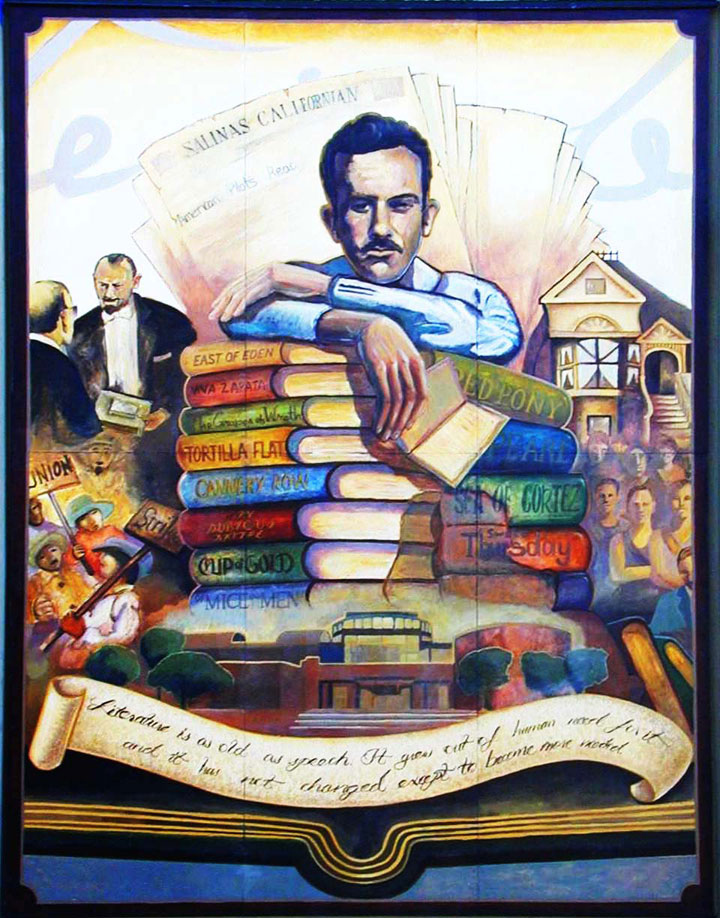

John Steinbeck pondered the Salinas paradox wickedly in “Always Something to Do in Salinas,” a travel piece he wrote for Holiday magazine in 1955. By then Steinbeck had been a non-citizen of Salinas for 35 years—first as a college student at Stanford, later as a struggling writer in nearby Pacific Grove, finally as an international celebrity with homes in Manhattan and Long Island and instant recognition wherever he traveled. But John Steinbeck never forgot Salinas. And Salinas, I found, never forgot or forgave John Steinbeck for what he wrote about the town.

I learned for myself that, as Steinbeck joked, Salinas just is. But the Salinas that is isn’t the town I thought I was seeing when Allen and I passed through on our Highway 101 artichoke pilgrimage seven years ago. Normal Salinas weather is, as Steinbeck noted, not sunny, but high gray fog. Even in summer the gloom is damp and dark, enveloping Salinas like a shroud delivered from the angry sea. Robert Louis Stevenson, the first literary tourist who recorded what Salinas was before John Steinbeck described what Salinas is, compared the newly named Salinas City unfavorably with coastal Monterey, a Catholic enclave with European roots and old world ways. Stevenson, the son of a Scottish Presbyterian engineer, described Salinas City as an isolated Protestant village dredged from the Salinas River wetlands by sharp-elbowed Yankees, ex-Confederate Southerners, and ambitious immigrants who connived to make upstart Salinas—not established Monterey—the new county seat. Government and agriculture are still the main business of Salinas. Tourists still favor Monterey.

Highway 101: Escape Route from Salinas to High Culture

“People wanted wealth and got it and sat on it and it seemed to me that when they had it, and had bought the best automobile and had taken the hated but necessary trip to Europe, they were disappointed and sad that it was over. There was nothing left but to make more money. Theater came to Monterey and even opera. Writers and painters and poets rioted in Carmel, but no of these things came to Salinas. For pure culture we had Chautauqua in the summer—William Jennings Bryan, Billy Sunday, The World of Art, with slides in a big tent with wooden benches. Everyone bought tickets for the whole course, but Billy Sunday in boxing gloves fighting the devil in the squared ring was easily the most popular.”

—John Steinbeck, “Always Something to Do in Salinas”

According to the Salinas historian Robert Johnson, Salinas had 3,300 residents when John Steinbeck was born in 1902 at his parents’ home on upscale Central Avenue. Despite its modest size, Johnson says that Salinas boasted six or seven churches when the town was officially incorporated in 1874. The most prestigious house of worship in Salinas was always St. Paul’s, the Episcopal church chosen by John Steinbeck’s ambitious mother Olive when the family moved to town in 1900 or 1901. But the high-grade culture John Steinbeck said Olive craved for her children was in San Francisco, a serious schlep by horse, train, or Model-T before Highway 101 finally reached Salinas. San Francisco, not Salinas, was The City for young John Steinbeck, as it continues to be for high-minded Californians like Olive today.

Not that the Salinas churches didn’t have culture of a sort in Steinbeck’s time. St. Paul’s in particular was a social center for the Salinas upper crust, with Sunday services featuring organ music, choirs, soloists, and a string orchestra for special occasions. Local land money built an opera house, and a grant from Andrew Carnegie helped pay for a public library. Parks, pleasure gardens, and cemeteries abounded in and around Salinas for citizens in good standing. But the fading names I deciphered on the crumbling headstones at the Garden of Memories are defintely “whites-only,” and the handful of Japanese and Filipinos who managed to buy land kept to themselves. John Steinbeck’s description of the evangelist Billy Sunday boxing with the devil at a Salinas Chautauqua event suggests that Protestant frontier spectacle, like Salinas society, was viewed through the rose-colored glasses of race-and-class certitude.

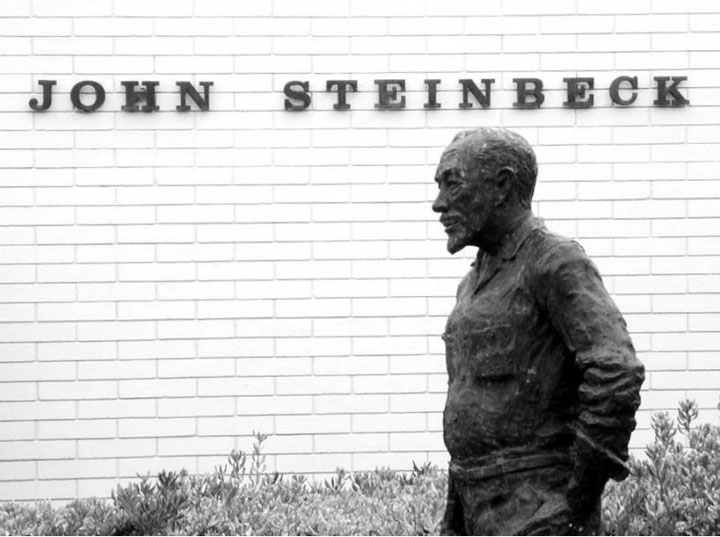

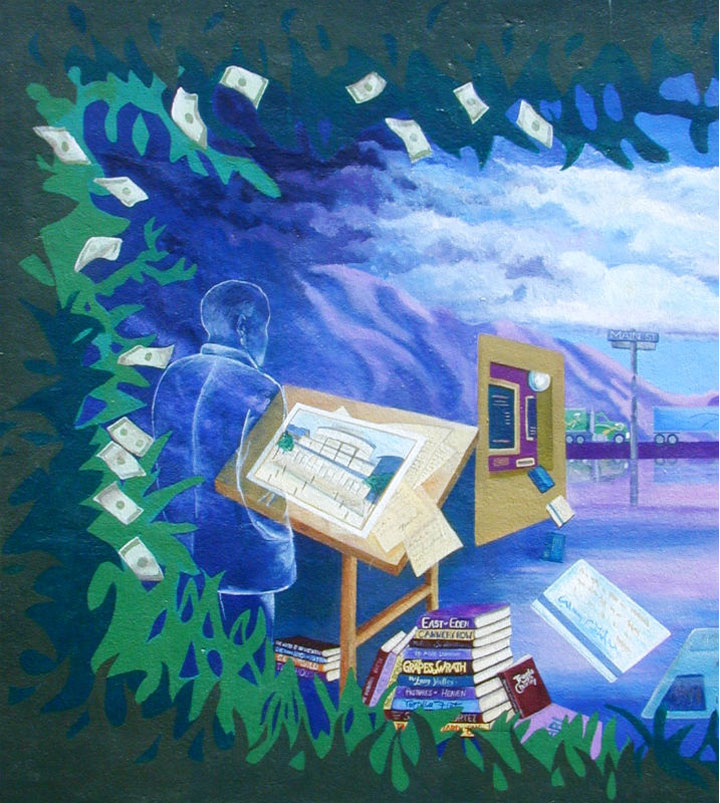

Artists and writers of the period colonized Carmel, not Salinas. They included literary socialists like Jack London and Lincoln Steffens and poets as divergent in style and stature as George Sterling and Robinson Jeffers. The Pacific Grove-Carmel-Monterey cultural axis, not Salinas, was John Steinbeck’s future, and he didn’t fight the call. Like St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in East of Eden, Salinas was a place sensitive souls like John Steinbeck and his character Aron Trask fled from, not to. Years later, when Steinbeck was too important to ignore, a faction in Salinas tried to name a road in his honor. Steinbeck insisted on a bowling alley instead. He won the battle but lost the war. The public library in Salinas is now the John Steinbeck Library. The massive museum on Main Street is the National Steinbeck Center. A dozen businesses with no connection to members of John Steinbeck’s family—all of whom departed Salinas by death or by choice—dot lower Main Street and the strip malls between downtown Salinas and Highway 101. The St. Paul’s parsonage described in East of Eden is now a law office. The church where Steinbeck played, prayed, and acted out in as a boy was torn down for a parking lot, usually empty.

Steinbeck-Denial and the Name-Game in Salinas Today

“We had excitements in Salinas besides revivals and circuses, and now and then a murder. And we must have had despair, too, as when a lonely man who lived in a tiny house on Castroville Street put both barrels of a shotgun in his mouth and pulled the trigger with his toes. That morning Andy was the first in the schoolyard, but when he arrived he had the most exciting article any Salinas kid had ever possessed. He had it in one of those little striped bags candy came in. He put it on the teacher’s desk as a present. That’s how much he loved her.

“I remember how she opened the bag and shook out on her desk a human ear, but I don’t remember what happened thereafter. I have a memory block perhaps produced by violence. The teacher seemed to have an aversion for Andy after that and it broke his heart. He had given her the only ear he or any other kid was ever likely to possess.”

—John Steinbeck, “Always Something to Do in Salinas”

John Steinbeck’s ashes reside not far from the new St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, occupied the same year Steinbeck satirized Salinas for Holiday. The Garden of Memories cemetery was unlocked and unattended the Sunday I visited, and the John Steinbeck plaque was hard to miss. Visible by virtue of inappropriateness, a tacky sign extends a painted finger to the clutter of weeds, wilted flowers, and cracked pavement leading to the Hamilton family plot where John Steinbeck rests. Nearby, an incongruous military tank rests on its concrete laurels next to the Garden of Memories mausoleum, a paradox on a pedestal making a statement I don’t understand and doubt Steinbeck would approve if I did.

John Steinbeck hated war. Salinas appears to hold a more benign view. The historical society grounds in North Salinas feature a display of oddly obsolete and out-of-place military hardware, public anti-art unique in my California experience. The John Steinbeck museum on Main Street shares space with a pocket park honoring local veterans of the Bataan Death March. Is this another Salinas-persona paradox, or a problem best kept to myself? On the right, the Republican, Rotarian Salinians, destested by John Steinbeck, who stayed and prospered in war and peace. On the left, John Steinbeck: New Deal Democrat, Cold War critic, prophet without honor in Salinas until he died. What middle ground could ever marry such opposites? Perhaps that’s why Steinbeck abandoned his Salinas relationship: irreconcilable differences until death do us part.

The Salinians I asked about my problem avoided politics and talked about personalities. The identity of Salinas citizens Steinbeck is thought to have portrayed in his books is the preferred topic of conversation. Opinions are definite but don’t always agree. An ex-parishioner of St. Paul’s expressed her confidence that Steinbeck patterned his character Andy—the Salinas boy who taunts the Chinaman in Cannery Row—on her grandfather, a church and school contemporary of Steinbeck who stayed in Salinas and lived to a ripe old age. A local expert on Salinas history is equally certain this isn’t so. An informed source in Pacific Grove who interviewed the person in question maintains an open mind on the subject.

John Steinbeck’s Salinas: The Forgotten Violence of 1936

“The General took a suite in the Geoffrey House, installed direct telephone lines to various stations, even had one group of telephones the were not connected to anything. He set armed guards over his suite and he put Salinas in a state of siege. He organized Vigilantes. Service-station operators, owners of small stores, clerks, bank tellers got out sporting rifles, shotguns, all the hundreds of weapons owned by small-town Americans who in the West at least, I guess, are the most heavily armed people in the world. I remember counting up and found that I had twelve firearms of various calibers and I was not one of the best equipped. In addition to the riflemen, squads drilled in the streets with baseball bats. Everyone was having a good time. Stores were closed and to move about town was to be challenged every block or so by viciously weaponed people one had gone to school with. . . .

“Down at the lettuce sheds, the pickets began to get apprehensive. . . .

“Then a particularly vigilant citizen made a frightening discovery and became a hero. He found that on one road leading into Salinas, red flags had been set up at intervals. It was no more than the General had anticipated. This was undoubtedly the route along which the Longshoremen were going to march. The General wired the governor to stand by to issue orders to the National Guard, but being a foxy politician himself, he had all of the red flags publicly burned on Main Street.”

—John Steinbeck, “Always Something to Do in Salinas”

The epic suffering of the Joads in California enraged the state and alarmed the nation, as John Steinbeck intended when he wrote his masterpiece. But before sitting down to write The Grapes of Wrath in 1938, he composed an unpublished piece about Salinas he called L’Affaire Lettuceburg, a bitter indictment of the violence with which Salinas responded to the 1936 strike by produce packers from the Alisal, an area east of Highway 101 called Little Oklahoma. Warned by his wife Carol that he was writing too close to home and far beneath his capacity as an author, Steinbeck started over again, shifting his vision from Salinas to California’s Central Valley and completing The Grapes of Wrath 60 miles north of Salinas in Los Gatos. But he neither forgot nor forgave what happened in Salinas in 1936, returning to the episode in his piece for Holiday and holding it in his heart, according to his letters, with a indelible mortar of anger and pain. Yet no one living in Salinas today, or with parents living in Salinas at the time, was willing to talk with me about Salinas under martial law 80 years ago.

The burning of The Grapes of Wrath in Salinas in 1939 (and maybe in 1940 as well) is another story. Period photos and first-hand accounts are pretty convincing, and most Salinians I spoke with acknowledge their credibility. A recent book about the extreme reaction to The Grapes of Wrath throughout America both dates and locates the 1939 burning of the book in Salinas. I learned about the later burning from a taped interview with the late Dennis Murphy, the son of John Steinbeck’s church and school mate John Murphy and the author of The Sergeant, an under-appreciated novel that Dennis Murphy completed with John Steinbeck’s encouragement and scripted into a 1968 movie starring Rod Steiger. But this evidence failed to dissuade Salinas enthusiasts who are engaged in an effort disprove that The Grapes of Wrath was ever burned publicly in Salinas.

Highway 101: Today’s Salinas Exit, Yesterday’s Social Wall

“All might have gone well if at about this time the Highway Commission had not complained that someone was stealing the survey markers for widening a highway, if a San Francisco newspaper had not investigated and found that the Longshoremen were working the docks as usual and if the Salinas housewives had not got on their high horse about not being able to buy groceries. The citizens reluctantly put away their guns, the owners granted a small pay raise and the General left town. I have always wondered what happened to him. He had qualities of genius. It was a long time before Salinians cared to discuss the episode. And now it is comfortably forgotten. Salinas is a very interesting town.”

—John Steinbeck, “Always Something to Do in Salinas”

According to Robert Johnston’s history, following World War II Salinas city leaders tried to mend fences with the Okies east of Highway 101 in a top-down electoral campaign to incorporate the Alisal into Salinas. But the files of the period I found at St. Paul’s make me doubt the Salinas fathers’ motives as much as their methods. Richard Coombs, the young rector recruited from New York to build a new church for St. Paul’s, reminded his parishioners that they had sinned and fallen short by failing to extend the church’s ministry to the people of the Alisal when help was needed. By the time Coombs arrived in Salinas, the Episcopal bishop in San Francisco had mandated an Episcopal mission east of Highway 101 to fill the gap. Another mission was started in North Salinas, and a third was later established in Corral de Tierra, the setting of Steinbeck’s Pastures of Heaven. It’s called Good Shepherd; Steinbeck’s heavenly pasture is an upscale enclave of luxury homes, horse ranches, and golf-and-tennis clubs—precisely the future Steinbeck predicted for Corral de Tierra in 1932.

Incidentally, I was invited to speak recently to a Rotary meeting at a Corral de Tierra tennis club where a celebrity tournament was underway, a media circus that required the Rotary meeting to move to the club bar. I felt at home I suppose, but I could have been in Aspen or Boca Raton, other pastures where I’ve also enjoyed bar life among the affluent. This week I was back in Salinas to play for the Christmas Eve service at St. Paul’s. Arriving later than expected because of heavy Highway 101 traffic, I looked for a quick place to eat before the choir rehearsed at 8 p.m. Pulling into a tony restaurant near St. Paul’s, a favorite of the Sunday church crowd, I watched the Open sign in the window fade to black as lubricated patrons pushed past my car on their way to the parking lot. A straggler, a Salinas matron with a voice like a chain saw, clipped my bumper with her handbag. “Jesus!” she screamed, pounding my trunk. “You’re moving too fast. Now I think I’ll just a move little slower so you’ll be even later to wherever the hell you think you’re going!”

Mouthing a Merry Christmas, I turned toward the fast food place advertising Open Till 8 across the street. Inside, the young lady who took my sandwich order smiled and apologized for having to close early for Christmas, explaining that this was her first fast-food job and she knew people would still be hungry. I tipped her $10 for my five-dollar meal, and this time I meant it when I wished her Merry Christmas. I felt better about Salinas because of her, and I hope she finds something to do in Salinas and stays in John Steinbeck’s home town. But I have my doubts. And I’ve made my last late-night drive to foggy Salinas. Playing the organ at St. Paul’s has been wonderful and I’ll miss everyone. But I’ve gotten the best gift an outsider like me can expect from Salinas: John Steinbeck. No doubt at all about that. And John Steinbeck travels well.

“Sang’s Cafe” in Salinas, photograph by Jessie Chernetsky courtesy of the artist.